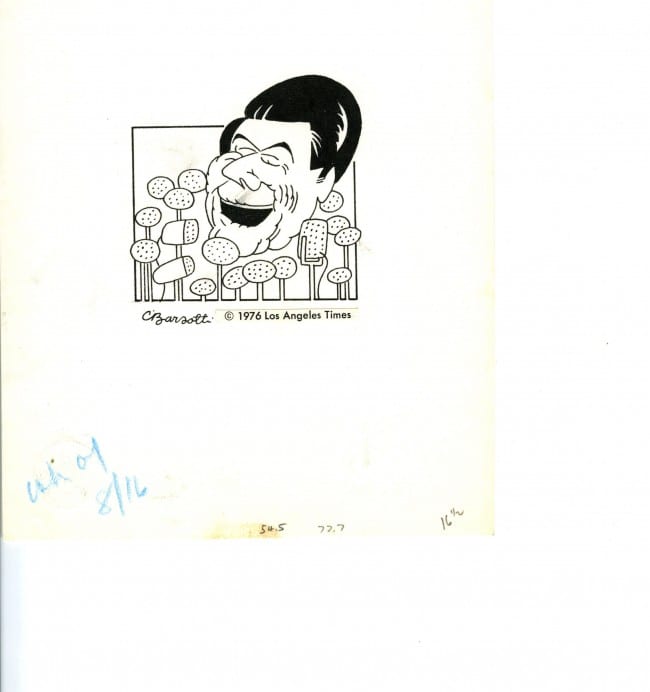

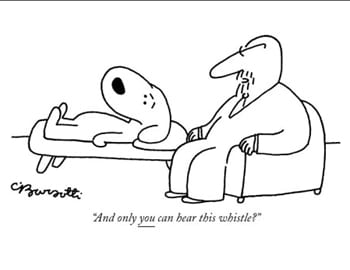

In 1990, Charles Barsotti received a piece of fan mail from another Charles – Charles Schulz – who wrote: "I think the little dogs you draw are the funniest cartoons that anyone has been doing in recent years" –signed, "Sparky." Having the creator of Peanuts tell you that he thinks you draw cartooning's funniest dogs is a little like having Tiger Wood express envy for your follow-through. Snoopy and Charles Barsotti's "little dogs" bear some little resemblance to one another, though Barsotti uses even fewer lines than Schultz to sketch his even more psychologically complex canines. And while Snoopy's persona expanded over the decades, gestating most elaborately into a British fighter pilot, nemesis of the Red Baron, Barsotti's cute little mutts always work under the radar.

Charley Barsotti lives in Kansas City, Missouri, with his wife Ramoth, who occasionally joined us as we spoke in the artist's studio not long ago. We covered Barsotti's Texas upbringing, his years at Hallmark in Kansas City, his brief stint as cartoon editor at The Saturday Evening Post in New York, and, of course, his long career at The New Yorker.

GEHR: You were born in San Marcos, Texas, correct?

BARSOTTI: I was born in my grandmother’s house in 1933. Her name was Branum. I don’t think I knew, or remember, her first name.

GEHR: You don’t remember your grandmother’s first name?

BARSOTTI: Well, she died. My father used to tell me I missed knowing one of the greatest ladies he had ever met, my mother’s mother. And apparently she really doted on me in my very early years. My dad, Howard, was from Chicago; came down to San Antonio, Irish-Italian.

GEHR: Were your parents religious people?

BARSOTTI: Do we have to go into that? Mother [Dicey Belle Branum] was from a Southern Baptist family. They had to leave Tennessee in the Civil War. One of those "Gone to Texas" types. There were stories about the wagons and Indians. Her family was very much Southern Baptist. Dad was this Italian harsh guy coming down from the big city with his city ways; a bit of a "dude." There was much hostility in her family, my dad told me, until this grandmother whose name I can’t remember set everybody straight.

GEHR: What was San Antonio like back then?

BARSOTTI: Everything down there either had thorns on it or it bit – and that includes the adults. It was a really nifty place, actually. We lived in a real neighborhood on the south side of town. We’d call it semi-rural, almost joking, but it really wasn’t. It was lower-middle class, with middle-class values, striving hard to become real middle class. Both of my parents worked very hard.

GEHR: Is that where you acquired your work ethic?

BARSOTTI: I must have, yeah. That, and fear. My mother was a schoolteacher.

GEHR: What did she teach?

BARSOTTI: My very earliest memory of her as a schoolteacher was before I started school: She was teaching in a two-room schoolhouse out in the country, so she was teaching everything. History was her main subject. She finally got in at Hot Wells, which was my school. I went all the way from first grade through high school at Hot Wells. My mother put me in the first grade when I was five years old. She pulled some strings, which I’m still upset about. At one point Charles Schulz and I shared that being the youngest boy in the class was not really ideal. I was skinny, underweight, and untalented. [Laughs.]

GEHR: Where did you go to college?

BARSOTTI: Texas State, which is where my mother graduated with honors. I did not. After that was the Army.

GEHR: Did you cartoon in college?

BARSOTTI: Yeah, for the college paper, The Star. I was heavily censored. The president of the college would go over every single one of my cartoons and white stuff out.

GEHR: Such as?

BARSOTTI. References to beer. [Laughs.]

GEHR: What were your Army years like?

BARSOTTI: Hated it. Basic training was the worst time of my life. People were sent to recruiting stations. I was sent to Fort Sam Houston's Brooke Army Medical in San Antonio. My first wife was pregnant. I did what I was supposed to do and was glad to be there.

GEHR: What did you do after the Army?

BARSOTTI: I went back to school. I thought I was going to get a masters degree in education. I was working at the Brown School in San Marcos, where I'd worked as an undergraduate. It was a residential treatment center for people with special needs, and the guy running the place was doing something underhanded. So they suddenly said to me, "You run the place." I became director. I hired and fired and, I like to think, added dimension to the programs. It was a matter of trying to do what you could to make their lives a little more interesting. The president, Bert Brown, and I were good friends. He was a big theater buff, which suited me just fine.

GEHR: He took you on your first trip to New York, right?

BARSOTTI: He called me at work one day and said, "I want you to go home and just draw some cartoons, because you’re going to New York with me." So I went home. It was the first time I ever did any single-panel stuff.

GEHR: How old were you?

BARSOTTI: Old enough to be excited. I went to all the magazines. Esquire was not nice. Everybody else was wonderful, including The New Yorker. They bought.

BARSOTTI: Old enough to be excited. I went to all the magazines. Esquire was not nice. Everybody else was wonderful, including The New Yorker. They bought.

GEHR: How much were magazines paying for cartoons back then?

BARSOTTI: I thought I paid them! [Laughs.] It wasn’t very much, of course. The first check I got from The New Yorker was for an idea.

GEHR: Who drew your first gag?

BARSOTTI: I don’t remember. Chon Day did at least one, John O'Brien did one, and Otto Soglow did one that was quoted in the Austin newspaper. I got no credit in my almost-hometown paper!

GEHR: What was your first cartoon The New Yorker bought?

BARSOTTI: It was two people, a young man and a young woman, with "Ban the Bomb"–type signs. And one of them says, "Just think, if it weren’t for nuclear fission we would’ve never met."

GEHR: How did you end up at Hallmark in Kansas City?

BARSOTTI: I answered this ad in Advertising Age and got a call from this guy in Chicago. Hallmark then sent me a psychological test but I just set it aside. Then they shot Kennedy, and the atmosphere I ran into the next day in San Marcos was a little too much. I figured, "It’s time to buckle down, take the psychological test, and get serious about this." Anyway, Holly [William Hollingworth] Whyte wrote a book called The Organization Man, and he had things to keep in mind when you’re taking a psychological test for a big organization. I remembered to say things like, "I love my father and my mother both, but I love my father a little bit more." That kind of thing.

GEHR: Was Hallmark your first real art job?

BARSOTTI: It was really writing, at first. I was in the editorial department and then switched to contemporary cards.

GEHR: Was that where you began cartooning seriously?

BARSOTTI: Rapidographs had just come out and I splurged and bought myself a set. I was doing some sketches, and a friend of mine in a different department of Hallmark asked me if I would use that style to illustrate a little pamphlet of Ogden Nash poems. So I did it on my own time, and it got me in trouble in my department. That’s the way Hallmark's bureaucracy worked. That sort of set me off, and I sent some drawings to Mike Mooney at The Saturday Evening Post — and didn’t hear anything. The next weekend, I sat down and did another big batch of these things. I sent it in and thought, "Oh, this is it. This isn’t working." But! I got a call from Mooney at work. I thought it was a joke, but he said he had turned the big hallway at The Saturday Evening Post into a gallery. "I’ve got your cartoons up and down it," he said. He was a very ebullient fellow. Then I went there and met the editor, Bill Emerson.

GEHR: What did you do for the Post?

BARSOTTI: I started doing a regular feature called "My Kind of People." I did some two-page spreads and that kind of led into the feature. Then one day they called and said, "Come up here and be cartoon editor." So I did. It took me about three months before I felt like I had a handle on it. And then I thought, "This is what I wanna do. Forever." I loved it. I tried to do a comic strip, but not for me was the comic strip.

GEHR: So let me get this straight. You moved to Kansas City to work at Hallmark in ’64, and you were there until ’68?

BARSOTTI: Yeah, ’68 was my year at the Post, which folded in January ’69. We lived in Larchmont for a while. My first wife found this house in Mamaroneck, which was not as fancy but turned out to be a wonderful neighborhood.

GEHR: You were also working on a daily strip called "Sally Bananas." What were you trying to do with it?

BARSOTTI: It was just whimsical. This girl character ran around this park and she was barefoot and had a few friends. It was just hopeless and the syndicate stuff got all screwed up the summer after the Post folded. At the time I’d been on every elevator in New York City. [Laughs.] It was coming together, but in my mind it wasn’t coming together at all. But that didn’t work out. And then somehow, I think after too many drinks, we decided to come back here to Kansas City.

GEHR: It sounds as though the Post's demise was traumatic for a lot of people, including George Booth.

GEHR: It sounds as though the Post's demise was traumatic for a lot of people, including George Booth.

BARSOTTI: Bill Emerson asked William Shawn to talk to us. The way Emerson told me later, Shawn asked, "Is there anything I can do?" when the Post folded. And Emerson said, "I’d like you to talk to Barsotti and Booth." We were going to jump the gun on The New Yorker with George Booth. I think they had probably seen George first, but were maybe a little slower about deciding to publish him. I’m not sure about that. Anyway, George came in one Wednesday, when people used to make the Wednesday rounds – which really is a thing of the past, of course. George came one late afternoon and said in this drawl – I remember this exactly: "My wife and I have been looking at stuff in the magazine, and we though maybe, because of that, you’d appreciate my stuff." Later, in a speech, George said, "I didn’t know at that point that Barsotti was a religious man. But he looked down at the stuff and said ‘Jesus Christ.’" [Laughs.].

GEHR: Did you have a good meeting with Mr. Shawn?

BARSOTTI: The week after the Post folded, Mr. Shawn had me in and really made me feel good. He just had this wonderful empathetic...I can’t remember a word he said, except for "We hope you stay in cartooning." Very formal yet very vague at the same time. He had a very powerful effect on me because I felt good for a while. [Laughs.] He said, "I’d like you to meet my art editor." I didn’t understand that The New Yorker was more magic than logical. I just knew that Mr. Shawn had said some nice things and made me feel a hell of a lot better. But he didn’t say "We’re going to give you a contract."

GEHR: What happened when you met Jim Geraghty, the art editor?

BARSOTTI: Frank Modell sat in on it. We had lunch, and I thought it would be like a corporate lunch. I don’t know what the hell it was. It was just extremely awkward, but nice. Later, Geraghty was very upset when I said we were moving back to Kansas City. He didn’t think it was a very good idea. He chased me down the street, as a matter of fact. Literally. And he caught up with me.

GEHR: To try to talk you out of it?

BARSOTTI: Yeah. So did other people.

GEHR: Did he offer you a contract when you met him?

BARSOTTI: No. Still nothing. Free-lance stuff. I went out to Newsday with the comic strip. Bill Moyers was publisher at the time.

GEHR: When did you get your New Yorker contract?

BARSOTTI: It was around Christmas '69. Geraghty, in his mystical Irish way, said something like, "By the way, we would like to have legal recognition" – some phrase like that – "between the two of us. You might take this to your lawyer, look at it, see what you think." I went to lunch with a Newsweek writer and said, "I think I might have just been offered a contract." And that’s what it was. But there was no hint of it ahead of time. I would never have gone down the painful path of the comic strip if I had known. George Booth got his contract at the same time I got mine. George was an immediate hit, but I wasn’t.

GEHR: What happened when you moved back to Kansas City?

BARSOTTI: It must've been '70 or '71. The divorce was later, after we got back here. I can't blame it all on the fall of The Saturday Evening Post, but that really tore me apart. My comic strip was a mess and I got too involved with politics, with the [Vietnam] war stuff. In 1972 I was the Democratic candidate for congress.

GEHR: That's walking the walk.

BARSOTTI: No! It was awful! And only people in New York appreciated it. That's for true. It was the third district in Johnson Country, heavily Republican. They later had a democratic congressman for a couple of terms, but it was just awful.

GEHR: You won the nomination but lost the election.

BARSOTTI: Yeah, I just stopped. I said, "I withdraw, I can't do this." They were making deals with people I didn't want to talk with. We'd been involved with getting the right people to the state Democratic convention and this just kind of happened. We did no planning at all. A friend of mine said, "You have never shown a propensity for suffering fools gladly." And I thought, nonsense. But I'm just not good at that, so it was a terrible experience. I must have been out of my mind. But I thought the Vietnam War was a horrible, horrible mistake.

GEHR: What made the campaign so hard?

BARSOTTI: I was doing the comic strip and doing cartoons. We finally had to just fold the comic strip. Things just kind of fell apart. I'm not gonna say moving back here was a mistake, because I wouldn't have met Ramoth. The kids are all doing OK. They get a little antsy once in a while. "Why in the hell did you move us back here?!"

GEHR: Tell me about getting sued over an early drawing you did for Playboy.

BARSOTTI: Around the time of my divorce, Michelle Urie at Playboy said, "We like your cartoons, but our readers like sexy stuff. Could you give that a shot?" So I gave it a shot. The first one was mild enough. But I guess I wanted the setting to be kind of formal. I was using a different drawing style. A little bit more ornate. Fanciful. It was supposed to be real upper class, and I got it into my head that he should have an English title. But it turns out that if you name somebody Lord Something, and there's somebody by that name, there's only one in the world. Who knew? In fact, one of the questions they asked me at the deposition was, "Are you familiar with Burke's Peerage?" I said I'd heard of it, which I had, but didn't know anything about it. It was Lord Cowdrey, and Lord Cowdrey was not amused. So Playboy ended up tearing out all those pages in the British edition. But let's not open this again. Because I know how it was settled but I'm not supposed to talk about that. And I won't. This particular Lord Cowdrey's dead, but he has a son, who I believe called it to his father's attention.

GEHR: Crazy story.

BARSOTTI: An unhappy one for me. I'm still embarrassed about it.

GEHR: Whom else were you working for when you returned to Kansas City?

BARSOTTI: I did a lot of art for The New York Times op-ed page and for The Kansas City Star. Real political stuff.

GEHR: I've always wondered how The New Yorker's first-look rights applied to someone doing as much free-lance art as you. Does that mean that everything you did, regardless of whom it was for, had to go to The New Yorker first?

BARSOTTI: Back when I took it seriously. [Laughs.]

GEHR: You make it sound like a gentleman's agreement.

BARSOTTI: Gosh, you’re making me sound like a non-gentleman. Actually, [art editor] Lee [Lorenz] said, "If it’s obviously for Playboy, I don’t need to see it." Yeah, it’s recognized in the breach — is that the proper phrase? I don’t know where that came from. Well, if it sounds good, hell, let’s stick with it. [Laughs.] I did color stuff when Fortune had this small-business magazine. They used a couple of rabbits as young small businessmen, and it was in color, so I didn’t send those. So if it’s obvious, I just don’t. They still get a lot of stuff from me.

GEHR: Do you feel strongly enmeshed in The New Yorker's cartoon tradition?

BARSOTTI: Oh, sure! The whole damn thing. I was very much into the history, the tradition of it. I’ve read all the books and everything until I got to The Last Days of The New Yorker by Gigi Mahon. I decided at that point that maybe it’s better to let this stuff go. She was pretty bitter. That was a period when I was really glad I was in the Midwest and not up there in New York.

GEHR: Which cartoonists influenced you the most?

BARSOTTI: Well, Sam Cobean. And I wanted to be Clarence Darrow Jr. for a while in my youth, but that didn’t work out. But, my goodness, looking at these names, so many people.

GEHR: Do you feel as though the single-panel cartoon has run its course?

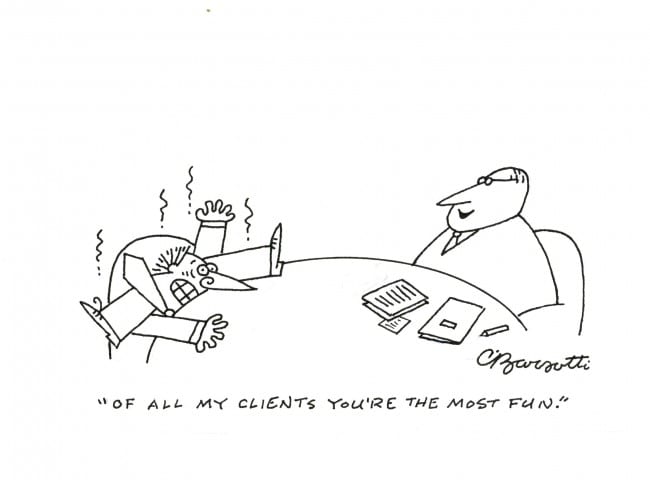

BARSOTTI: It was a nice run, wasn’t it? I was thinking about that the other day. it’s like we’re the last wheel in town, which can sometimes be just frustrating as hell when they don’t share my enthusiasm for a drawing. What do I do with it then? Sometimes, if it’s really timely, I can change a caption or something. But I love the single-panel cartoon! I felt strongly about it at the Post. I hated to see the general-interest magazines go; all the cartoons they served. The New Yorker has a different audience. It allows you all kinds of references. And I would rather go out in a blaze of glory, speaking for The New Yorker. In a blaze of good cartoons.

GEHR: Do any younger New Yorker cartoonists turn you on?

BARSOTTI: I’m trying to think. I’m thinking! I’m thinking! No. There's one guy who draws pretty well, and I can’t think of his name right now. I don’t think a cartoon needs to be ugly. It can be mean, it can be pointed, it can be satirical, it can do a lot of things, but it doesn’t have to be ugly. This is, after all, The New Yorker. David Remnick has said, "We’re a magazine, not a museum." But there is such a strong, wonderful history behind all of this, and I don’t think you'll find too many cartoons from that tradition that are just out-and-out ugly.

RAMOTH BARSOTTI: Charley’s a tough editor. He would be like William Shawn.

BARSOTTI: I would be a wonderful editor! ‘Cause I like good —

RAMOTH: I know you would be. But you also have your sense of humor, which isn’t always like everyone else’s.

BARSOTTI: It's not supposed to be. I really appreciate the good ones.

GEHR: How would you describe Charley’s sense of humor, Ramoth?

RAMOTH: He has a good sense of humor. He’s kind of somber, though. He’s more on the quiet side. In a group you wouldn’t say, "Oh, there’s the cartoonist." No, he’s not that way.

GEHR: I’m always impressed by the gentleness of Charley's cartoons. How even when he's cartooning about the harshest social situations, there are no jagged edges. Maybe it's a Southern thing.

RAMOTH: Charley is very sensitive; he has that about him, too. He's a sweet person, really, even though he comes off as a curmudgeon sometimes.

BARSOTTI: Yeah, my kids seem to use that word excessively. [Laughs.]

GEHR: Have you ever taught cartooning? Do you have any theories about humor or cartooning?

BARSOTTI: I tried that once, really stupidly, at the Kansas City Art Institute, some sort of summer class. They really weren’t interested. I didn't have any theories.

GEHR: How did you prepare for it?

BARSOTTI: I didn’t. I just thought, "Well, yeah, cartoons, sure, I can — " I showed examples and stuff like that. Once, when I was traveling somewhere, Russell Myers [Broom Hilda] took over a class for me. Russell’s a big collector of originals; I think he’s even got a Krazy Kat. "I couldn’t believe it," he said. "I had all these wonderful things I laid out for them. But they just sat there. As a young man I would’ve knocked people over to see them."

GEHR: You're famous for your dog cartoons, of course. Are the dogs you draw based on any particular dog you've owned?

BARSOTTI: No. The dog I dedicated They Moved My Bowl to, Jiggs, was a dog I had when I was a lad. He was a great dog, a dachshund and something else. He was run over by a car — broke my little heart. Actually, the dog character sorta changed. The first ones I did were almost feral dog-like animals.

GEHR: The pup is rather iconic, isn't it?

BARSOTTI: In England, our friend Michael Wolff sold the Niceday stationery company on using the pup in all their packaging, promotion, and advertising. He conceived that and sold it to them in 1990 or early '91, which I still think is remarkable. It was a terrific experience and we're still doing it. It's been a good run.

GEHR: Your drawings, and the dog cartoons in particular, seem to have become increasingly clean over the years, until now some of them have fewer than a couple of dozen lines.

BARSOTTI: I distilled both the caption and the cartoon. You want the caption to be conversational, so that’s got to be boiled down to whatever you've got in mind. And, yeah, I like to simplify very much. There was a cartoon not too long ago – I don’t even remember who did it and I should, one of the newer ones [Nick Downes] – that was set in a doctor’s office with a sign that said, "Thank you for not mentioning Dr. Oz," which I thought was wonderful. But the way I’m working now, if I’d thought of it I’d need a doctor's setting. Now, what I am pleased to be able to do is show the doctor in a white coat, with the stethoscope over here, and he's talking to somebody. And you’ve seen a doctor’s office, so I don’t need to show what they look like. And it pleases me a lot that I can distill it to that point and it still works. The same goes for the aggressive/evil businessman, whichever one you want. The less important characters in medieval paintings would be smaller. So when I have somebody picking on somebody economically, I just draw the picked-on person small. I like that kind of shorthand. It allows for a more abstract type of situation.

BARSOTTI: I distilled both the caption and the cartoon. You want the caption to be conversational, so that’s got to be boiled down to whatever you've got in mind. And, yeah, I like to simplify very much. There was a cartoon not too long ago – I don’t even remember who did it and I should, one of the newer ones [Nick Downes] – that was set in a doctor’s office with a sign that said, "Thank you for not mentioning Dr. Oz," which I thought was wonderful. But the way I’m working now, if I’d thought of it I’d need a doctor's setting. Now, what I am pleased to be able to do is show the doctor in a white coat, with the stethoscope over here, and he's talking to somebody. And you’ve seen a doctor’s office, so I don’t need to show what they look like. And it pleases me a lot that I can distill it to that point and it still works. The same goes for the aggressive/evil businessman, whichever one you want. The less important characters in medieval paintings would be smaller. So when I have somebody picking on somebody economically, I just draw the picked-on person small. I like that kind of shorthand. It allows for a more abstract type of situation.

GEHR: Lee Lorenz wrote that you consciously changed your style when Robert Gottlieb became editor and started to do more collaged and ornate drawings.

BARSOTTI: Yeah. I don’t think Gottlieb liked my stuff particularly; I got that kind of feeling. I changed the style and did some running puns. But I thought I just amusing Lee.

GEHR: For example?

BARSOTTI: "El L. Bean," with a bean in a sombrero. Just terrible. [Laughs.] It was only meant to be an inside joke, ‘cause I thought it was so extreme and awful. But I didn’t tell him not to buy it!

GEHR: And the collage cartoons?

BARSOTTI: Oh, yeah, I was shameless. That was a lot of fun, but it was Glen Baxter-ish in the extreme. I would go through old comic strips and find things that, taken out, would just amuse me. So, that was still doodling, but yeah, there’s "The men from the Pasta Squad." That was the kind of stuff they were buying. It's fun when you have an editor who’s enthusiastic.

GEHR: Have you done collage work in the last decade?

BARSOTTI: No, can’t get away with much of it. Once I used a photo of Humphrey Bogart's head, and he's sitting at a counter with Miss Cheeses of the World.

GEHR: What was your artist-editor relationship with Tina Brown like?

BARSOTTI: She was very strange, as far as I was concerned. When she met with the cartoonists, she was very nice and knew my work. I think things were maybe a bit sluggish at first. Tina loved and responded to cartoonists’ work about power. I did one of two businessmen with lion's heads: "I'm taking you to the Four Seasons. You'll enjoy the fear." There are differences you pick up with these guys. The guy from Random House was full of crap.

GEHR: You mean Bob Gottlieb?

BARSOTTI: He asked Lee, "Why don’t we have another Peter Arno?" "That’d be interesting. I’ll see if I can find one for you." [Laughs.]

GEHR: What are these imposing stacks?

BARSOTTI: They are just what they are. They are cartoons The New Yorker didn’t buy – things they haven’t bought yet, is the way I’d like to look at it.

GEHR: You draw fairly close to the size your work is printed, don't you?

GEHR: You draw fairly close to the size your work is printed, don't you?

BARSOTTI: Yup. On Strathmore paper cut to this size. What Lee snottily referred to as – what does he say? "I send my cartoons in on index cards." [GEHR laughs.] That’s not an index card; this is an index card. But yeah, I do that for whatever it’s worth.

GEHR: You told me you never do roughs. Have you ever done them?

BARSOTTI: I guess I have. Yes, with the Post, sure. And I told you about the breakthrough with the Rapidograph. Those were very quick cartoons.

GEHR: So you stopped roughing when you discovered the Rapidograph?

BARSOTTI: Yeah. Now the roughs essentially disappear, because I draw pencil before I ink over it. And another good reason I use Strathmore is because I can erase a lot, and it’s still good paper. I just work until I get it.

GEHR: How big are your batches these days?

BARSOTTI: Not like they used to be. I think I sent in six this week. I’ve cut the batches down. And they changed the meeting day, when Bob and David supposedly sit down together, to Tuesdays. And I used to really emphasize Monday and Tuesday in my work schedule. Now I’ve got to switch it back to the way I did before and do more work at the end of the week. So I send it in Monday night.

GEHR: What are your favorite cartoon clichés? The desert island? The Grim Reaper?

BARSOTTI: I’m not sure I’ve ever done a desert island. I might have.

GEHR: Why not?

BARSOTTI: No reason. And as for the Grim Reaper: I just never drew one I particularly liked. I start off sketching, and if it’s no fun to draw, what fun can it be to look at? [Laughs.]

GEHR: Do you ever have afterthoughts about your work? Do you ever wish you'd drawn something differently?

BARSOTTI: No, not really, not consciously. Once I did these businessmen making fun of people on the street, beggars. You know, "Move to Sweden." And I think I put tails on the bad guys. Now I kind of wish I hadn’t. Not that I think they’re any less devilish now. [Laughs] But just looking at the cartoon, I don’t think I would. I'd still give ‘em sharp teeth, though. That was called for.

Special thanks to Jack McKean and Kristen Bisson for transcription excellence.