Tom K. Ryan died March 12 in Florida. He had devoted 42 of his 92.8 years to the production of a daily comic strip that was among the bellwethers of fresh comedy in newspaper comic strips in the middle of the 20th century. Westerns were all the rage in television of the 1950s and 1960s, and Ryan caught the wave with Tumbleweeds and helped turn comic strip humor in a new direction.

The first of the new style-setters was doubtless Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, which, in the simplicity of its drawing style, was, eventually, widely emulated. But the comedy in Peanuts was also different. Humor arising from a dichotomy—what I call "non-sequitur humor"—is another aspect of Peanuts that set a new comic-strip fashion. Or, if it did not exactly set the fashion (a debatable point since the "sick jokes" and "elephant jokes" of the '50s turned on a similar comic device), it was at least the first strip to capture and capitalize on a mode of humorous thinking then "in the air."

Two other new strips that had at their core some adaptation of the principles of non-sequitur humor are B.C. and Tumbleweeds. In each strip, as in Peanuts, the adaptation is original, inventive, and highly individual, and in each strip, the reader found again the devices and techniques made familiar to him in Peanuts— artwork deceptively simple, personality traits sharpened nearly to the point of eccentricity, repetition of set prices, the running gag, animals with human aspirations.

When Johnny Hart's B.C. began in 1958 (February 17), the comedy at first sprang from our recognition of a discrepancy between the visual and the verbal, between the setting of the strip and the concerns of its characters. The setting was prehistoric; the concerns, the preoccupations, are ours of the twentieth century. Hence, even in this unlikely setting, we were delightfully surprised to discover— ourselves.

In Tumbleweeds, which began in September 1965, Ryan built up the ideal of the Old West and then punched holes in it. The discrepancy or dichotomy was between the myth of the Old West and its reality. Ryan's characters set the stage with their diminutive cuteness: They are so tiny and cute that we expect to encounter here an adolescent’s rosy version of the Old West. Ryan inflates the speech of his characters to match the yearnings that the pictures aspire to express, but the facts of life deflate this scenario.

The dialogue abounds in the cliches and doggerel mythology of the dime-novel Western, but reality is seldom as highflown as the prose. The title character's steed is not the noble cliche of yesterday's Roy Rogers movie: He's a moth-eaten army surplus sway-backed cayuse, and he can never quite live up to the aspirations of his master who celebrates in his mind's eye the wild and wooly West of Hollywood, not historical fact. And the fact is that his horse Epic can never jump across those gullies that yawn like chasms before him. Tumbleweeds, despite his aspirations, must live in this world, not in his dreams.

Ryan had aspirations of his own, and they included cartooning almost from the beginning. Born July 6, 1928, in Anderson, Indiana, he cartooned from the age of nine. But he also aspired to a college education: he received basketball scholarships, but chose another course. He studied business for a year at Notre Dame University and liberal arts for two years at the University of Cincinnati. Then he dropped out.

By then, Ryan was married and needed gainful employment to sustain his wife and growing family. He tried all sorts, reported Jud Hurd at Cartoonist PROfiles. He worked in a factory, as a lineman for the phone company, and even sold furniture.

Eventually, he found a job in the art department of a printing company and that led to another job, this time in commercial art with an advertising agency. Ryan’s specialty was cartoon advertising. He took a correspondence course in commercial art that helped him fine-tune his art and cartooning skills, according to TheCartoonists.ca, and he spent the next 10-12 years in commercial art, first with a studio then on his own.

“During the fifties,” said Hurd, “Ryan submitted, with little luck, a few gag cartoons to the major magazine markets. Although he was able to sell a limited number of panels to various trade magazines, the small pay was not encouraging.”

He had better luck freelancing editorial and sports cartoons to newspapers in Anderson and nearby Muncie, Indiana.

And he also tried selling a comic strip. Entitled Benny Beans, the strip was entirely different from Tumbleweeds, Ryan told Hurd. “More corn,” he said, probably tongue-in-cheek. He submitted the strip to all the syndicates. But no success. And he’s never spoken about it since.

And then in the late 1950s, as Tumbleweeds.com has it, “illness struck.” It’s not clear what the illness was because Ryan makes a joke out of it. Judging by the context, he may have been confined to bed for a time, and during that time, he found Zane Grey’s classic western novels and “fell madly in love” with them. “The illness,” as he says in a couple of places, “stayed with me the rest of my life.”

The ailment that endured was an affection for the Old West, the same Old West that was playing out on the nation’s tv sets. Ryan’s fondness for the genre took shape as gentle and loving ridicule in Tumbleweeds. The strip was, as Ryan said, “the untold story, from suppressed archives, of the Old West. the epic saga that inspired those immortal words of Buffalo Bill: ‘Go figure.’”

In concocting the strip, Ryan adopted a drawing style that he felt was distinctive, different from anything else on the funnies pages of the nation’s newspapers. Tiny bodies, big heads—just right for the shrunken dimensions of newspaper comic strips at the time. In 1965, the Lew Little Syndicate picked up the strip, and at the age of 37, Ryan embarked upon his life’s work.

Lew Little was the Johnny Appleseed of the syndicate business. With a degree in journalism, he worked as an editor for the Los Angeles Times, then at the San Diego Union, and then at the San Francisco Chronicle. Then he became a salesman for the Chronicle’s syndicate in 1962, leaving after two years to start his own syndicate with total resources of $1,200 in savings and a Volkswagen camper.

For the next several years, Little and his wife (journalist and author Mary Ellen Corbett) traveled the U.S. and Canada, living and working out of the camper, acquiring and selling newspaper features of all sorts, including comic strips. Little’s first major strip acquisition was Morrie Turner’s racially diverse strip, Wee Pals, which started early in 1965—the same year that Tumbleweeds joined Little’s line-up.

In 1967, Little merged his tiny operation with the Des Moines Register and Tribune Syndicate, becoming vice president and then president-editor. After five years, he left to join King Features, taking Tumbleweeds and Wee Pals with him. And when he left King for United Feature Syndicate in 1977, he again took Tumbleweeds and Wee Pals with him. Little would eventually return to King, again taking his favorite strips with him.

Tumbleweeds started dailies only, not adding a Sunday strip until 1968. Henceforth, Ryan had to crank out jokes and pictures 365 days a year without fail. Asked once how he did it, he replied only: “It’s a gift from God.”

But Ryan didn’t do it alone. He sometimes had assistants. From 1968 to 1978, his assistant was a Muncie kid named Jim Davis, who worked 3-4 days a week, inking backgrounds and details. Davis was also working up sample comic strips of his own. His first attempt, Gnorm Gnat, starred a bug and failed because syndicate officials believed most people don’t like insects. Undeterred, Davis next employed a fat orange cat, and before long, Garfield was a household name, and Davis built a studio complex near Muncie to produce and control the spin-off merchandising empire.

Ryan toiled on with new, unnamed assistants.

Over the years, Hurd observed, “Ryan has striven to improve the style and characterization in the strip. As an example, the artist points out that feet which have gotten bigger [doubtless another tongue-in-cheek observation]. Other small changes have allowed the strip to keep pace with the times. The characters have developed to such an extent that subtle expressions and body language have become important facets of the jokes.”

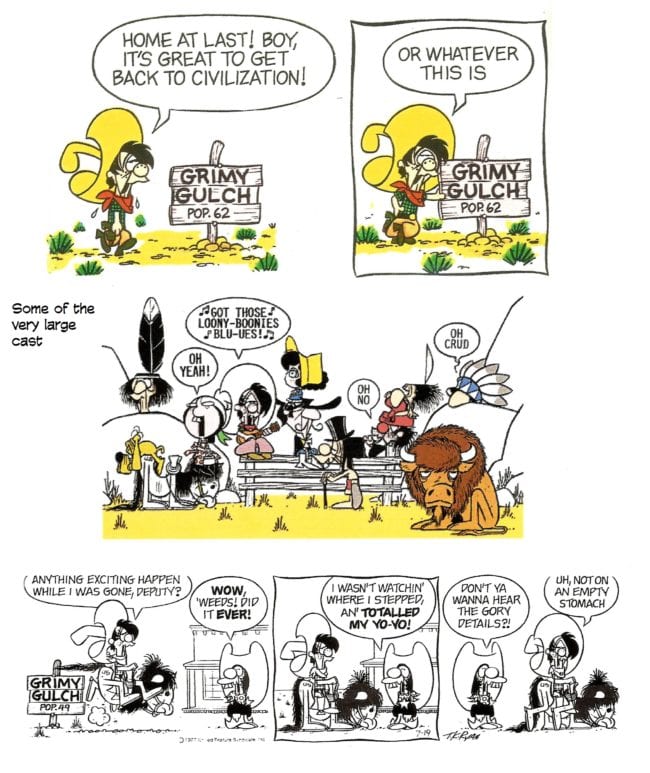

To help him conjure up gags, Ryan introduced nearly forty characters, each a fountainhead of the kind of eccentricity that refutes the legends of the Old West. It starts with Tumbleweeds himself, a laconic cowpoke who might prefer to be somewhere other than Grimy Gulch—somewhere as heroic as a Hollywood western, say— but has no real ambition to do anything heroic and does it with all the enthusiastic lassitude he can muster to the task.

On every hand in Tumbleweeds, expectations built on the Old West of motion picture and legend are disappointed. The sheriff, the luxuriously mustachioed short-handed “long arm of the law,” can capture the town hoodlum, but can't lock him up in jail. He is assisted by the extravagantly dim-witted Deputy Knuckles who can’t be trusted to carry a gun so he has a yo-yo. Judge Horatio Curmudgeon Frump, a pompous windbag who boasts he cannot be bought but is open to rental, is blind to justice. The heroine, Hildegard Hamhocker, the town’s only known fully-grown woman, is not a modestly blushing shy young desert blossom: she's painfully plain and aggressively desperate to catch a man.

Nearby at Fort Ridiculous, the 6 7/8 Cavalry is posted, commanded by Colonel G. Armageddon Fluster (a play on General Armstrong Custer of Little Bighorn infamy), whom the local Native Americans, the Poohawk tribesmen, call “Goldilocks” or “Poopsie.”

Not even the Native Americans live up to our Hollywood expectations. Hardly savages, they must go to school and take evening classes in the theory and practice of bloodthirsty warfare. The Poohawks are led by a chief who is always lamenting his tribe’s pathetic standing as Indians.

He has a beautiful daughter—“a flower among the weeds”—named Little Pigeon, who is being courted by Limpid Lizard, a classic klutz, and Lotsa Luck, a very rich Poohawk (whose horse is “driven” by a chauffeur, Drudgeworth), and Bucolic Buffalo, the biggest and strongest Poohawk (but he isn’t very smart).

Oddly in this day of easily bruised sensibilities, throughout the run of Tumbleweeds, Native Americans wrote Ryan to say how much they enjoyed the strip.

Other evidence of popularity was attained by Grimy Gulch’s undertaker, Claude Clay, who was voted an honorary member of the Arizona Funeral Directors, Inc., in April 1977.

Even if our fond anticipations are destined to be blighted, the lesson of the strip is not bleak. Tumbleweeds' dreams may be doomed to disappointment, but there is no bitter disillusionment here— only a remarkable resilience. The characters turn quickly from their fancies to the facts and embrace reality. Hildegarde wants Tumbleweeds as her husband, but, in the last analysis, any man will do. The realities do not crush these pint-sized dreamers; nor do they quite wake them up.

The humor in the new midcentury strips like Tumbleweeds is more sophisticated than comic strip comedy had been in the past. The humor of Blondie was, and is, humor appropriate to the setting in which the characters are developed and appropriate to the characters themselves. The success of the punchline does not rest on our ability to recognize a dichotomy or discrepancy between characters and setting, dialogue and action.

The humor of Bugs Bunny or of Donald Duck does not originate in their being animals behaving like humans as it does with Snoopy in Peanuts. They are animals behaving like humans but that’s not the source of the comedy. Nor, in these two strips, does the comedy come from the animals behaving like animals as it sometimes does in Pogo or in Animal Crackers.

The humor in the strips of this new tradition— Peanuts, B.C., The Wizard of Id, Tumbleweeds, Animal Crackers, to name a few— is more sophisticated because it depends on our recognizing something that is only implicit in the strip. We laugh at B.C. because we are shown childlike men, men just beginning to be men, trying out civilization, and we see what they do not: that, like a suit that's too large, civilization doesn't quite fit.

We laugh at Tumbleweeds much of the time because we recognize that the real Old West was quite different from the West that tiny Tumbleweeds tries to reenact whenever moved to action. If we didn't know that trains run on round wheels along smooth rails, Thor's choo-choo in B.C. wouldn't appear funny to us at all. If we didn't know that most cowboys' horses don't jump wide canyons in a single bound, Tumbleweeds' dashed hopes would be tragic instead of comic. But we do know these things, and upon that knowledge the humor of these strips is built.

At age 81, Ryan decided to lower the curtain on this epic satiric epoch. He chose retiring himself and his strip instead of leaving it all to someone else to continue, ending its 42-year run with the last daily on December 29, 2007; the last Sunday, the next day. According to report (which I only vaguely remember), in the last daily, Tumbleweeds is astride Epic and they both are overlooking a canyon chasm while Tumbleweeds says something the double-meaning of which is lost on anyone who doesn’t realize it’s the farewell strip.

At the time of its cessation, Tumbleweeds appeared in about 200 newspapers; at its peak, it may have appeared in 400-700 papers, reports vary.

Tumbleweeds and his diminutive gang worked outside the newspaper realm, too. One of the Tumbleweeds strips was animated for an appearance in The Fabulous Funnies, a 1980 television special that showcased several comic strips. Tumbleweeds Gulch was an attraction at MCM Grand Adventures Theme Park, saith St. Wikipedia, and the strip was also the basis for a Las Vegas stage show. In 1983, Tumbleweeds was adapted into a musical comedy for high school productions.

But it was in ink on paper out of T.K. Ryan’s possibly perverse mind that Tumbleweeds, Hildegard Hamhocker, the Poohawks and all the rest re-enacted an Old West that no one had ever seen before but that everyone could find him/herself in.

The humor of dichotomy— because it points to a discrepancy, a non-sequitur— is inevitably sobering. In Tumbleweeds it isn't just the Old West that the characters try to create with their language, and it isn't just the Old West that can't live up to its poetry. Man hovers between the lines here, and he is a bit short of his vision of himself too. Just as he is in B.C. and in Peanuts, the other pacesetters for a new age for comedy in comic strips. Seeing ourselves in comic strip comedy displays the spark of divinity in humanity: in laughing at ourselves, we rise above ourselves.