Spain Rodriguez acknowledges that age hasn’t necessarily brought wisdom, but it does help him appreciate his youthful adventures more, especially the unique experience of growing up in Buffalo, New York in the 1950s, which he portrays in his latest book, Cruisin’ With the Hound. “I’m probably more introspective now because I’m an old fella,” he allows. “Nobody knows what’s going on in your head. In a lot of ways that’s what literature and comics are about. The thing about comics is it’s an excellent vehicle to report what’s going on in your head. So that’s what I’m doing.”

Spain Rodriguez acknowledges that age hasn’t necessarily brought wisdom, but it does help him appreciate his youthful adventures more, especially the unique experience of growing up in Buffalo, New York in the 1950s, which he portrays in his latest book, Cruisin’ With the Hound. “I’m probably more introspective now because I’m an old fella,” he allows. “Nobody knows what’s going on in your head. In a lot of ways that’s what literature and comics are about. The thing about comics is it’s an excellent vehicle to report what’s going on in your head. So that’s what I’m doing.”

It doesn’t mean that there’s a moral to his new collection of graphic short stories, but at least the statute of limitations protects both the innocent and guilty alike in these candid and confessional tales.

“I’m kind of a ham,” he admits. “I get up on stage and I seldom experience stage fright. Maybe it’s some kind of egomania on my part, but it seemed like this is how I experienced these events. I had a lot of things to learn, but I was definitely up for adventure.”

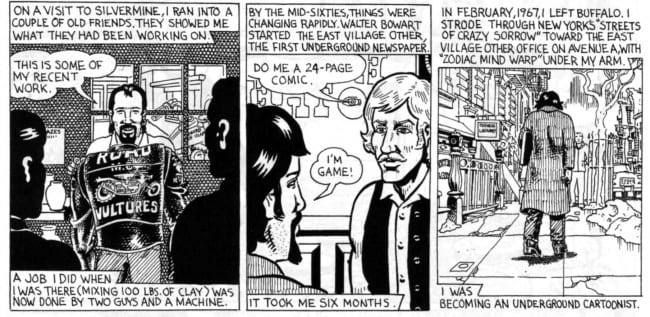

The book’s title, Cruisin’ With the Hound, refers both to rock and roll deejay The Hound Dog, who provides the soundtrack for Spain’s street stories, but also to the man behind the wheel of their cruisemobile, Fred Tooté. These two set the scene in this insider’s account of the '50s and ;60s in a working class city in western upstate New York, where Spain was schooled in the facts of life, became a member of the North Fillmore Street intellectuals and the Road Vultures Motorcycle Club, and grew into the rebel artist who found himself in the center of the emerging counterculture revolution.

Cruisin’ With the Hound might be the sequel to My True Story, his 1994 collection of similar autobiographical stories. That book relates riding and rumbling with the Road Vultures, plus it includes a number of his historical accounts of class struggle and revolution around the world. This new volume from Fantagraphics Books tells more about his childhood, the guys and girls in his neighborhood, early encounters with sex, religion, and science fiction, and the birth of rock and roll. Not only do these stories give readers access to a special era in cultural history, but they also give the cartoonist the opportunity to eulogize two of his personal heroes.

The Hound, whose real name was George Lorenz broadcast “the new sound going down” on WKBW- 1520 AM and later on WBLK 93.7 FM, bringing the songs of Little Richard, Fats Domino, Clyde Mcfatter, and Elvis Presley to a waiting and willing teenage audience tired of their parents’ music. He was hep before hip, and his musical influence was felt across the Eastern Seaboard and north into Canada. Lorenz christened himself with that nickname.

“One of the jive expressions at the time was if you were hanging around the corner, you were doggin’ around. So I’d come on and say, Here I am to dog around for another hour. That’s how they got to call me the hound dog,” he explains on one of the numerous websites devoted to his memory.

In most of these stories The Hound Dog is an audio presence, an unseen but important part of the fevered atmosphere, providing the songs that energized the action. “All you coolers and foolers out there, it’s the old Hound Dog for Mulroney Motors with ‘Strange Love’ by the Native Boys.”

“This is it, man,” says a young Spain to his convertible companions. “This could be the greatest rock ‘n’ roll record ever.”

When a listener asks The Hound to play “The Poor People of Paris” by Andre Previn, he refuses. “We don’t know no poor people of Paris here, man. The only poor people we know are the poor people of William Street.”

During a drunken party while Spain attempts to seduce his date The Hound spins “Yama Yama Pretty Mama” by Richard Berry, “Give Me Some Cherry Pie” by Marvin and Johnny, and “Mama Said” by The Shirelles.

Lorenz dated the mother of one of the kids in Spain’s neighborhood, so they’d see him around now and then. One night in front of Chuckie’s house they spotted The Hound sitting in the back of a squad car, arrested for a domestic dispute. “It’s a bad day for Old Daddy Hound,” he moans.

“I’m sure The Hound was greatly embarrassed to be seen in the back of a cop car but to us it was further evidence of common experience,” reads the narration to this scene.

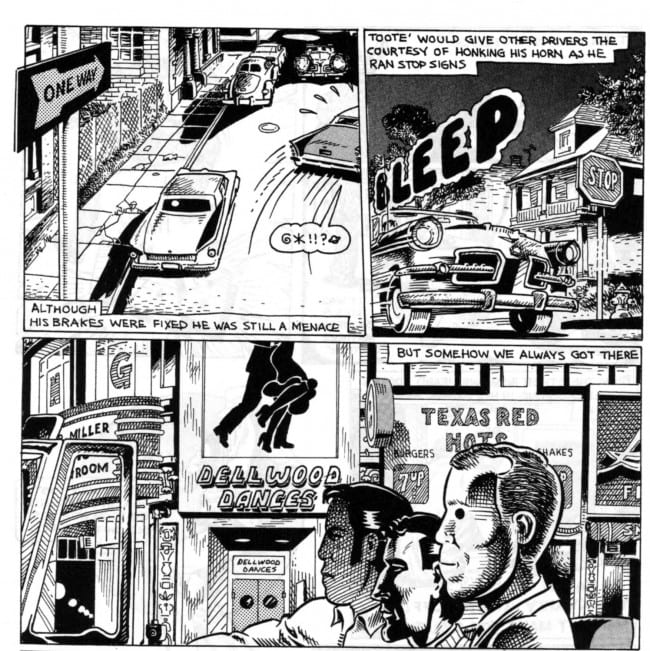

Fred Tooté also gets star treatment in Cruisin’ With the Hound. Spain, Tooté and their buddy Tex are like the Three Musketeers – fighting, philosophizing, cruising for babes, drinking in bars, scarfing Watt’s famous Bar-B-Q pork sandwiches, and driving up and down the avenues, looking for excitement. Fred is the craziest by far, driving like a maniac, climbing up the walls of buildings, espousing outlandish theories, and making a public display of himself whenever possible. Inhibitions are not part of his makeup. Once he got into booze and speed, it all went up a notch, recalls Spain. “Fred collected National Enquirer when it was real gory and he would go through these periodic things of finding Jesus. When he came down from the speed he’d have some kind of return to Jesus so he ripped up all his National Enquirers.”

Fred Tooté also gets star treatment in Cruisin’ With the Hound. Spain, Tooté and their buddy Tex are like the Three Musketeers – fighting, philosophizing, cruising for babes, drinking in bars, scarfing Watt’s famous Bar-B-Q pork sandwiches, and driving up and down the avenues, looking for excitement. Fred is the craziest by far, driving like a maniac, climbing up the walls of buildings, espousing outlandish theories, and making a public display of himself whenever possible. Inhibitions are not part of his makeup. Once he got into booze and speed, it all went up a notch, recalls Spain. “Fred collected National Enquirer when it was real gory and he would go through these periodic things of finding Jesus. When he came down from the speed he’d have some kind of return to Jesus so he ripped up all his National Enquirers.”

Buffalonians of his generation lived through a special era and his old friends still celebrate their roots, according to Spain, who feels a compulsion to tell their stories to the rest of the world. One of his earliest comic strips at the East Village Other featured a balding, retirement-age Road Vulture reminiscing about the good old days when the club offered a case of beer if you ran over a pedestrian with your bike. Cruisin’ With the Hound is the culmination of that compulsion.

“One of my main motivations is that I don’t have to tell these stories any more, especially stories about Fred Tooté. Fred died, as he predicted, a hideous death. He fell asleep with a lit cigarette in a drunken state and burned himself up. His brother is still alive, Vezay, the Dali Llama of Fillmore Street.”

The authenticity of his reflections is enhanced by the accuracy of the background details. The restaurants and bars, the neon display signs, the cars, the clothes, and the blocks of storefronts are true to life, or to a life that once was. “I have that kind of memory. I’m always observing things and checking things out and looking at what people are wearing. I have notebooks upon notebooks.”

He also has reference photos to work with. “I would go back to Buffalo periodically and I would take photos. It’s interesting. Hardly any of those buildings are there now. My old neighborhood is a freeway interchange. Whenever I run into people from that time period they all remember those days. I thought it was me. I thought it was some personal quirk remembering Buffalo in those days but in Buffalo itself there’s a whole cult around that.”

Much of his old stomping grounds has been altered, and not for the good, in his opinion. “People see the heritage of that era when somehow the economics lined up so these architectural monuments, these beautiful things were built. People are becoming more and more aware that this is a special age and certainly compared to the bleak, featureless, functional architecture that’s replacing this stuff. All this architecture was magical. You see this historically. Now they have these insubstantial plastic signs that are all square and not built to last because people don’t expect they will last but in those days there was a sense that you built these metal signs with neon and the stuff is going to last indefinitely. Buffalo has become kind of bleak, but when I was there, there was all this neat stuff.”

Spain has become a hometown hero who made a name for himself in the outside world and when he visits he is sometimes asked to speak at the local college or make an appearance at a bookstore or comic shop, or even invited to a beer bash at the Road Vultures clubhouse, where he is still on the roster. There is still one group that hasn’t embraced his success, he says – the same cops who used to inform him that he had no rights when they pulled over his motorcycle for an impromptu safety equipment check, or tossed him in the back seat of the patrol car for “suspicious behavior.” They sent him a special invitation to visit them next time. “I have a copy of Subvert #2 that’s signed by all these tactical patrol units in Buffalo, this kind of Gestapo they had, saying, oh, you like to see cops killed? We want to see you next time you come to Buffalo.” Spain snorts. “I’ve been back to Buffalo a bunch of times.” It’s on his itinerary for promoting his newest book this spring.

The Road Vultures were part of the avant garde, he insists. They refused to wear obedience suits and displayed club spirit when push came to shove. His association with that group reflects his personal values – standing up for the individual and against the homogenization of America. Laying it on the line when you do what you have to do. One for all and all for one. Accepting his role in the proletariat was a visceral gut level reaction more than an intellectual decision.

The Road Vultures were part of the avant garde, he insists. They refused to wear obedience suits and displayed club spirit when push came to shove. His association with that group reflects his personal values – standing up for the individual and against the homogenization of America. Laying it on the line when you do what you have to do. One for all and all for one. Accepting his role in the proletariat was a visceral gut level reaction more than an intellectual decision.

“I was walking down the street with some friends of mine and I saw all these bikes taking off from a street light and I said, I have to have one. I had some money saved up and I got one.” He rode with friends for a while and became aware of the various clubs in the local area. “I’d known a few Road Vultures. Some of our friends got jumped at this bar, so a whole bunch of us were supposed to go down there to find the guys who had jumped them and deal with them. Exact some justice. So me and these two other guys, foolishly, without waiting for all the other guys to show up, we walked into this bar and got stomped. I kept on fighting until they knocked me to the ground and somebody kicked me in the head and then I just curled up into a ball and let them beat up on me. When I went back to the bar where all the bikers hung out the Road Vultures were really impressed with my fighting spirit, so I got into the club, what they call striking. You hang around with the guys and they see if they like you and they vote on you.”

Once in, he never wanted out. “I’m still on the books. There are new Road Vultures – all the young guys are keeping it going, but us old guys, we just call each other up and see what kind of health we’re in.”

Over the past four decades, he has drawn numerous comic accounts of that era in Zap, Arcade, Weirdo, Blab! and in several of The Comics Journal Special Edition. Now they can all be re-read in anthologies. “If I live long enough, I’ll do stuff about other periods, like here in San Francisco when I first got here and on the Lower East Side. They were replete with many adventures.”

What lessons can the young people of today take from your stories, he is asked? “Good question. Each moment is unique. That’s the thing about comics. If affords you the potential to be able to capture that moment, probably more than anything else. It has certain objective and subjective potentiality. It’s something that nobody else can do. Each person is unique, each person sees things in their individual way and comics give you that opportunity.”

So a 25-year-old cartoonist today could tell his own story and it would be just as exciting as his from fifty years ago? “I wouldn’t go that far,” he laughs, but then reconsiders. “I’m sure they do and I look forward to it being chronicled.”

The most recent strip in this collection is the story "A High Smile Guy in a Low Smile Zone", which appeared in Blab! in 2006, and recounts his years working at the Western Electric factory, which manufactured telephone wire.

“It was one of the greatest experiences I’ve had, just being in this factory. It was like some sort of surreal wonderland with all these incredible machines, and being a janitor, even though it doesn’t have much status but in a lot of ways it’s the neatest job because you get to roam around this plant.”

Not that he’d want to work there again; once was probably enough and drawing comics is his real calling, but this is what youth provides the mature artist – the raw material for stories.