Ann Telnaes, editorial cartoonist for the Washington Post and a person I am delighted and proud to call “friend,” discussed recently the implications for her profession of the social media reactions to the notorious “Ted Cruz monkey children” cartoon she drew last December. Her article, which appeared at the Columbia Journalism Review website on June 29, 2016, appears below. As background, I’m reprinting forthwith the report I filed in my online magazine, Rants & Raves, Opus 347, last winter; here it is:

Cruz Makes a Monkey of Himself

A week or so before Christmas, Republicon prez candidate Ted Cruz released a self-glorifying tv campaign ad in which the Texas senator and his wife sit on the family couch while attentive, loving father Ted reads Christmas stories to his two daughters, ages 5 and 7, from books with such parody titles as How Obamacare Stole Christmas and Rudolph the Underemployed Reindeer and The Grinch Who Lost Her E-mails. At various intervals during the ad, viewers are invited to send in donations to obtain their very own copies of the books.

At the end of the bedtime reading, the older of the two daughters speaks up, gesturing and pointing and turning her head dramatically from left to right and back again and again, calling Hillary a grinch and attacking her about her e-mail server. The words she speaks are clearly not her own: she’s reciting lines written for her (perhaps by her doting father?). Hers is a Shirley Temple imitation, but, as one viewer reported, the girl looks more like she’s auditioning to be the next Money Boo Boo.

A few days later—on December 22—the Washington Post’s Ann Telnaes, a Pulitzer-winning cartoonist, posted the cartoon displayed hereabouts, depicting candidate Cruz as that old time entertainer, the sidewalk organ grinder, whose monkeys are trained to dance in tune with the music the organ grinder grinds out—a virtuoso image of precisely what Cruz does in the tv ad.  Telnaes’ Post cartoons are always animated, so in this one, Cruz the organ grinder grinds his organ and his monkeys dan`ce around. To me—and to any but the most fevered Right Wing-Nut viewer—the cartoon is attacking Cruz for turning his daughters into trained performers— monkeys— for the amusement of the passing multitudes.

Telnaes’ Post cartoons are always animated, so in this one, Cruz the organ grinder grinds his organ and his monkeys dan`ce around. To me—and to any but the most fevered Right Wing-Nut viewer—the cartoon is attacking Cruz for turning his daughters into trained performers— monkeys— for the amusement of the passing multitudes.

Cruz, of course, did not see it that way.

To him, Telnaes was ridiculing his daughters, not their father. He began at once frothing at the mouth with protective paternal rage —while at the same time rubbing his hands with mercenary glee. He was outraged, he said as loudly as he could, that his kids would be used as political fodder by an editorial cartoonist.

Telnaes acknowledged that the children of politicians are typically off-limits, but in this case, since the politician had used his kids as political commentators, satirists even, not just as members of his family, depiction of the girls was fair.

Cruz didn’t bother to disagree: he was busy sputtering outrage and then, in an ingenious effort to turn lemons into lemonade, asking his supporters to donate a million dollars within 24 hours so he could send the Post a message. He sent them all an e-mail with Telnaes’ cartoon in it, calling it evidence of the liberal bias of the news media. Tea Baggers lapped it up.

Suddenly, Telnaes’ editor, Fred Hiatt, yanked the cartoon, offering this lame explanation: “It is generally the policy of our editorial section to leave children out of it. I failed to look at this cartoon before it was published. I understand why Ann thought an exception to the policy was warranted in this case, but I do not agree.”

The news of Hiatt’s action spread quickly through the small but vociferous editooning community, inspiring a host of reactions—all supporting Telnaes. I do, too, in case it’s not obvious by now from the tone of my voice. I count myself a friend of hers, and I think this cartoon, like most of hers, is brilliant. The visual metaphor is apt for depicting what Cruz is doing and thereby is perfect for criticizing Cruz’s sleazy campaign tactics, exploiting his children for political advancement—not only with the original parody ad but in the subsequent solicitation for funds to attack the Post.

With the above as context, here is Telnaes’ June 29 article follows herewith, verbatim as it appeared in the Columbia Journalism Review website —

How Social Media Has Changed the Landscape for Editorial Cartooning

By Ann Telnaes

“You filthy kunt…a baseball bat to your head is now due.”

“HOW FUCKING DARE YOU CUNT. GET THE HELL OUT OF THE BUSINESS…”

“Bitch, your days are numbered.”

“Do the world a favor, go hang yourself”

“I hope you get raped to death”

I stood frozen in front of my computer, watching my Twitter feed roll like a slot machine reel. My editorial cartoon criticizing then-presidential candidate Ted Cruz for his decision to have his 7-year-old daughter read from the script of a political attack ad had just been published online by the Washington Post, and four days of continuous emails, tweets, and comments had begun.

Since my cartoon ran in December, I’ve thought a great deal about the role of social media in stoking the resulting outrage. Although passionate criticism over a provocative cartoon isn’t new, the introduction of social media into politics and election campaigning has dramatically increased the speed and intensity of those reactions, and the repercussions for the editorial cartooning profession. This has been especially true during the volatile 2016 presidential campaign.

Editorial cartoonists are a thick-skinned group; we’re used to getting negative feedback from irate readers telling us we’re idiots and how terrible our cartoons are. Many of my colleagues have received death threats as well—but this was different. In my almost 25 years as an editorial cartoonist, I have never received the level or amount of misogynistic vitriol I did over that cartoon. In addition to comments like the ones above, I was Twitter trolled, my archived cartoons doctored, and my photograph tweeted with the caption: “Makes fun of Ted Cruz’s children, aborted all of her own.”

Visual metaphors are an important component of editorial cartooning. They are the language we use to convey our point of view. The visual metaphor in this cartoon was an organ grinder, an early 20th century street musician who used leashed animals, usually monkeys, to collect coins from appreciative audiences. Because the point of my cartoon was to criticize Cruz’s decision to exploit his children for political gain, I drew him as a campaigning organ grinder with performing monkeys. This important part of the cartoon was lost immediately in the social media outrage fueled by tweets and comments from the senator and his supporters that mischaracterized the cartoon as attacking his daughters.

The Washington Post pulled the cartoon within hours and replaced it with a note from Editorial Page Editor Fred Hiatt, saying, “It’s generally been the policy of our editorial section to leave children out of it.” That was when the Cruz campaign reprinted the cartoon in an email asking for political donations to fight the “vicious personal attack on my daughters.”

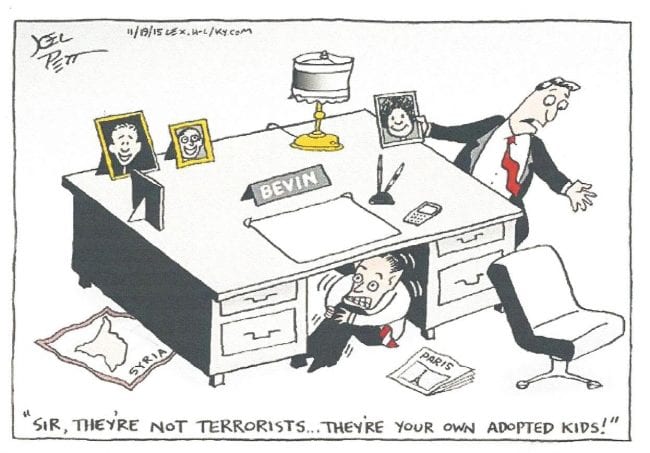

My colleague Joel Pett of the Lexington Herald-Leader had a similar experience last year with a cartoon criticizing Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin for his opposition to the resettlement of Syrian refugees—Bevin had claimed there was a possibility of terrorists entering the state. He called the cartoon racist because it mentioned his adopted children from Ethiopia, and he issued a statement condemning the newspaper for its racial intolerance and for attacking his kids. An online right-wing group picked up the story and continued the misrepresentation of the cartoon’s intent.

For 36 hours, Pett and the Herald-Leader received phone calls, emails, and social media messages demanding apologies. Pett and his editor responded that the cartoon was not racist. [A portion of my report on this matter last November appears down the scroll.—RCH] Pett’s experience, and mine, underscore how social media has changed the landscape for editorial cartooning—how it is being used as a tool of intimidation by interest groups and campaigns to try to silence criticism.

Through social media they can quickly mobilize their supporters and distribute misinformation, allowing mob mentalities to spread as soon as a cartoon is posted online. The medium is lightning fast and provides the protection of anonymity.

Add a news media that seems to value clickbait over presenting context about the editorial cartooning craft and often parrots the inaccurate characterizations the campaigns’ supporters spread, and you might as well paint a red bull’s eye on the cartoonist’s back.

During my four-day marathon of emails and tweets, I was trolled by a well known conservative cable news commentator who characterized my cartoon as attacking children and tried to bait me with insulting tweets. A member of the Cruz campaign communications team also trolled me, crowing that their “folks pushed back hard,” and “we won” after the cartoon was pulled. (Ironically, months later that same person was trolled herself with sexist tweets from Trump supporters.)

In the glut of coverage, most news outlets didn’t bother mentioning or showing the part of the video where Cruz had his daughter read from his political attack ad’s script. Except for a couple of print articles, including an informative piece by the New York Daily News that offered much-needed historical perspective about editorial cartooning, there was practically no coverage that explained what an editorial cartoon is supposed to do or the importance and use of visual metaphors. Instead there was outrage and talk about monkeys and children.

Many of my cartooning colleagues pushed back with thoughtfully-written (and cartooned) arguments about the purpose of an editorial cartoon; had they not done so, I would have faced the equivalent of being tarred and feathered, with cable news talking heads leading the way with torches.

Let me be clear: Even in the face of this kind of attack, I am not advocating limiting people’s right to speak, however obnoxious and offensive the language is (threats are not included in this; threaten bodily harm, and that’s where your free speech ends). I would much rather have an abundance of stupid, ignorant speech (as this political season is giving us) than watch a slow slide into self-censorship and possibly worse for my profession, with cartoon police deciding what can or cannot be drawn. I have spoken out publicly in support of cartoonists to freely express themselves without fear of imprisonment or threats, including the Danish cartoonists in 2006 and the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists in 2015, both of whom published cartoons of the prophet Muhammad.

The big worry for editorial cartoonists these past several years has been the widespread loss of staff jobs as newspapers fold or choose to eliminate their cartoonist in favor of buying syndicated cartoons. Finding paying work online remains problematic for cartoonists.

But the much bigger danger now is the use of social media to intimidate and silence, because it attacks the satirical core of what makes a cartoon an editorial cartoon. If we’re being harassed and pressured not to aim our pens critically, we won’t be able to call ourselves editorial cartoonists much longer—we won’t be able to create anything but mushy, uncontroversial drawings.

How should the journalism community protect cartoonists so they can do their jobs? We need to educate and be ready the next time a cartoonist aims his or her satire against a thin-skinned politician or interest group looking for an opportunity to manipulate fair criticism. Be aware when a false narrative is being presented to deflect the actual intent of a cartoon; talk to your editors and come up with a plan to counter the misinformation.

Instead of just hopping on the social media outrage bandwagon gathering clicks, media outlets need to do their homework, explaining the role in holding powerful people accountable that editorial cartoonists have had for centuries in America. Educate yourself about the components of an editorial cartoon, and how satire, irony, caricature, symbols, and visual metaphors all contribute to its makeup.

The US Supreme Court affirmed the essential role of editorial cartoons in a democracy when it ruled in the 1988 Hustler v Falwell case that satire is speech protected under the First Amendment. “Despite their sometimes caustic nature, from the early cartoon portraying George Washington as an ass down to the present day, graphic depictions and satirical cartoons have played a prominent role in public and political debate,” conservative Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote in the majority opinion. “From the viewpoint of history it is clear that our political discourse would have been considerably poorer without them.”

We might be wearing the metaphorical funny hat, but we take our jobs as journalists very seriously. It has been said cartoonists are on the front lines of the war to defend free speech. Don’t make the job easier for the social media lynch mobs by ignoring the threat their attacks pose to that freedom.

Ann Telnaes creates editorial cartoons in various media— animation, visual essays, live sketches, and traditional print— for the Washington Post. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 2001 for her print cartoons in the Los Angeles Times. Her print work was shown in a solo exhibit at the Library of Congress in 2004. That same year, her first book, Humor's Edge, was published by Pomegranate Press and the Library of Congress. A collection of Vice President Dick Cheney cartoons, Dick, was self-published by Telnaes and Sara Thaves in 2006. She is the incoming president for the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC).

[And now...back to Harvey]

Editoonist Joel Pett’s run-in with his state’s Governor-elect over an editorial cartoon was reported in Rants & Raves, Opus 346, the pertinent parts of which are:

MORE RACIST NONSENSE FROM THE RIGHT

Kentucky Governor-elect Matt Bevin has come out in opposition to resettlement of Syrian refugees in his state. Like many timorous Americans, he imagines terrorists lurking in the displaced multitudes. In response, Lexington Herald-Leader editorial cartoonist Joel Pett did a cartoon depicting Bevin as scared of his own adopted children who are from Ethiopia.

With my liberal bias, I see Pett’s cartoon as taking Bevin’s so-called “thinking” to its logical extreme: Bevin is being ridiculed as so fearful of Islamic hooligans infiltrating the ranks of Syrian refugees that he quakes even at photographs of his own adopted children from a Muslim country. (He has nine children, four of whom are adopted.) Bevin chose to respond to the cartoon by accusing Pett of racism:

With my liberal bias, I see Pett’s cartoon as taking Bevin’s so-called “thinking” to its logical extreme: Bevin is being ridiculed as so fearful of Islamic hooligans infiltrating the ranks of Syrian refugees that he quakes even at photographs of his own adopted children from a Muslim country. (He has nine children, four of whom are adopted.) Bevin chose to respond to the cartoon by accusing Pett of racism:

“They say a picture is worth a thousand words,” Bevin wrote. “Indeed, today, the Lexington Herald-Leader chose to articulate with great clarity the deplorably racist ideology of ‘cartoonist’ Joel Pett. Shame on Mr. Pett for his deplorable attack on my children and shame on the editorial controls that approved this overt racism. Let me be crystal clear,” he added, “—the tone of racial intolerance being struck by the Herald-Leader has no place in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and will not be tolerated by our administration.”

Jack Brammer at the Herald-Leader said that Bevin did not elaborate about how his administration’s intolerance of the newspaper’s racism might be manifest.

I suspect that Bevin’s anger was inspired as much by Pett’s invasion of his children’s privacy in the cartoon as by any political comment inherent in the ridicule—even though Bevin has used his children as political props when running for office. And Bevin is also seizing the opportunity to make a few political points about his administration’s posture on racism while attacking an opponent, Pett. Even if I understand his motivation, I don’t approve of it.

In a telephone interview, Pett said he was not a racist. “When Bevin has time to think about it—and there will be recurring criticism of his administration—I think he will view things differently.” He said he would “chalk up Bevin’s reaction to inexperience on his part.”

The Herald-Leader subsequently published a full response by Pett, full of sarcasm and truth. You can see it all at RCHarvey.com, Rants & Raves, Opus 346.