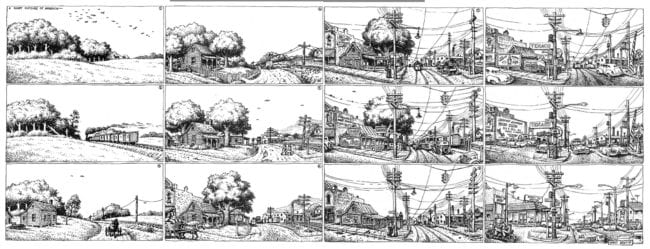

Robert Crumb's "A Short History of America" has always made me roll my eyes, despite the fact that I am largely in agreement with its conclusions. A brief summary of the strip: we start with an untouched landscape, with the implication that there is a great deal of beauty in its simplicity, although only received ideas would lead us to this thought, as the drawing here is less charged and interesting than what comes next. Clearly, Crumb's own feelings are muddy, as the strip advances the argument that we've sullied our world even as the artist's visual interest awakens in the depiction of our present and fallen situation.

Muddled or not, Crumb is correct. Few (if we are focusing on the readership of this publication) would argue against the idea that we've committed an irreversible crime upon the nature of this continent, and talking about this transgression in an eco-political magazine like CoEvolution Quarterly (where this now iconic strip was first published) makes perfect sense. "Short History" is regarded as a classic, an example of the heights that comic art can achieve, occupying a key place in the 1995 Terry Zwigoff Crumb documentary. What is implied for comics when a simplistic but extremely well-executed piece of political propaganda is seen as what the medium does best?

Crumb ends the strip with the only text to appear within it: 'What next?!!' What came next in comics of this ilk was a continued turning away from the present. Lesser artists like Seth took Crumb's lived-in and well-worn disgust and further simplified it, transforming it into an aesthetic argument against the reality we live in, but with even less search for proof. In a parallel-universe version of Crumb's strip, where environmental decline is substituted for the slackening of cartoonists' engagement with the world, Crumb's clear thought occupies panel 1: 'We've taken natural beauty and made it ugly.' The aesthetics of Palookaville reside in the hell of the panel 12: 'It was better when people wore suits all the time!'

Lee Friedlander's Albuquerque, New Mexico exists in the same moment in time as Crumb's strip, and confronts the same dilemma: the arbitrary sprawl that we've created and choose to live in. But unlike the Crumb of "A Short History", Friedlander decides to open his eyes to a wider landscape, and there is genuine pleasure to be had in what he perceives. This composition of stoplights, crude wire, and harsh foliage unnerves you with its lack of perfection and unity (which nature itself always has); Friedlander presents the image as its own type of nature. There's a thrill to how it all looks, an exhilaration in all the directions and angels this still moment suggests. More importantly, the human creativity that went into constructing this small corner of the world is acknowledged, while not offering an endorsement of the construction. This twin impulse (criticism and embrace) cuts deeper than Crumb because richer thinking and feeling are elicited, even allowing for negative thought, by perceiving things head on. Both Friedlander and Crumb edit and manipulate, but with Albuquerque the template allows for more freedom within the editing. Crumb offers a closed system. Art that moves people in a way that actually matters contains a rich tapestry of emotions and thoughts that the artist tries to congeal within the works chosen parameters. Why do comics so often spurn this approach, instead embracing the one-sided, or more often, the sentimental?

Most Crumb fans probably consider themselves opposed on principle to the aesthetics of Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams, but I don't find this famous sequence from Green Lantern #70 to be that different than "Short History". A well-intentioned moral lesson becomes meaningless when processed through O'Neil and Adams' hammy storytelling and beats. Like Crumb on the environment, the complexity of the issue at hand here (why a superhero ignores racial injustice within his own country) is too much to bear for the structure that the artists have built to discuss it. Green Lantern turns away from the stark injustice presented to him in the same way he'd turn away from a made up planet being sucked into a black hole: like a bad actor with no actual feeling or depth. Even if Adams bothered to draw Green Lantern with the human emotion he seems to think this story contains, you'd need a refutation (or a backbreakingly ridiculousness justification) of Green Lantern's accepted galactic police role to even begin a serious attempt at discussing all this. One wing of comics praises "A Short History of America" as containing actual social critique, while another praises Adams and O'Neil's run on Green Lantern as an important step in bringing 'adult ideas' into comics. They were both important, but not as actual revelations about how the world is constructed. Instead, their importance is in glorifying the artists that made them, so as to indicate that they think about deep stuff. But are they significant in moving our minds beyond cliché? Comics seem to suffer from a confusion that merely attempting to discuss something serious makes it serious.

Enter: Will Eisner, still considered an intellectual force in cartooning. The most respected award in comics is named after him and his work receives breathless praise from almost all corners. Significantly though, aside from technique, it's rarely discussed what, exactly, Eisner is so beloved for. I think people have a vague notion that he was 'serious' despite the lack of proof of this in his work. In fact, the counter proof is what exists. When you are confronted with his thoughts and ideas, a lot of the dysfunction of comics crystalizes.

One of Eisner's acknowledged classic works is "The Story of Gerhard Schnobble", a Spirit yarn from 1948. Eisner said this was his favorite all-time Spirit tale, remarking, 'It was the first time I could do a story that I had great personal feelings about.' The Smithsonian Collection of Comic Book Comics selected "Schnobble" to represent Eisner within its authoritative pages.

A shame, then, that this is perhaps one of the most appallingly corny comics you'll probably ever read, genuinely creepy in its gross sentimentality. 'THIS IS NOT A FUNNY STORY!!" Eisner warns on page 1. Yeah, it's not funny, but it is laughable. The plot: a sweet nebbish (his name is Schnobble, if you didn't get the message from how he's drawn) is fired from his job. He has the ability to fly but has kept it a secret. After losing his job, to prove his self-worth, he decides to finally reveal this ability. As he jets around the city, he is 'tragically' caught in a stream of bullets that resulted from a conflict the Spirit was engaged in. But don't worry, Schnobble can still fly... as an angel!

What great personal feelings can Eisner have actually felt he was imparting us with here? I really have no idea. I can't even guess, that's how empty it feels. Even more mysterious, the world of comics continues to maintain that this story holds something mature within it. Comics self-caricatures itself as barren of thought, and then elevates attempts at complexity to the forefront. Of course, to accomplish this sleight of hand, actual expression must be either misunderstood or discarded.

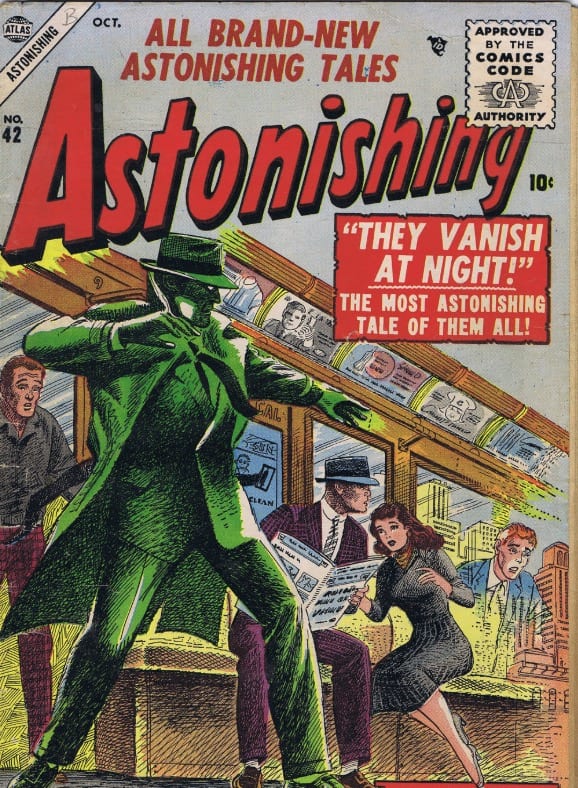

The standard equation is still: Eisner = serious practitioner, '50s horror comics that didn't come from EC = schlock. But when I look at the above Carl Burgos cover, the opposite seems so obvious. Put aside that Burgos doesn't showboat his technique like Eisner, preferring a quieter expression. The real story here is how creative this image is. Atlas Comics were drawn on tight deadline with no cultural respect or significant financial reward in sight for the artists. Burgos, of course, isn't even credited on his cover. And yet here is an image unlike any other I've seen. It communicates its idea clearly (supernatural menace threatens populace) but also suggests something beyond its stated intention of 'spookiness': a hollow outline of a dangerous entity, without any indulgence of a socially relevant zombie schtick. The drawing itself horrifies because it's creative, an original image that suggests a deeper vein of thought that we begin to confront in our own minds. Hollowed out people, merging together, no expression: it makes cliched sense in the abstract, stark and moving sense in the specific. Poetry.

I imagine Burgos came up with this drawing on the fly, fighting against time to make something effective. Rather than weighing his ingredients to make a 'serious statement' recipe, he improvised and expressed himself. The backwards structure of the Golden Age did a lot of damage to artists, but it also created an environment where images like this could come about and meet the eyes of thousands of readers on the newstand. Actual horrific imagery speaking to a reality that only the image itself can truly define, devoid of cliché (save a whiff or two), on display for the world to see. And Burgos made countless images like this, every month, for years.

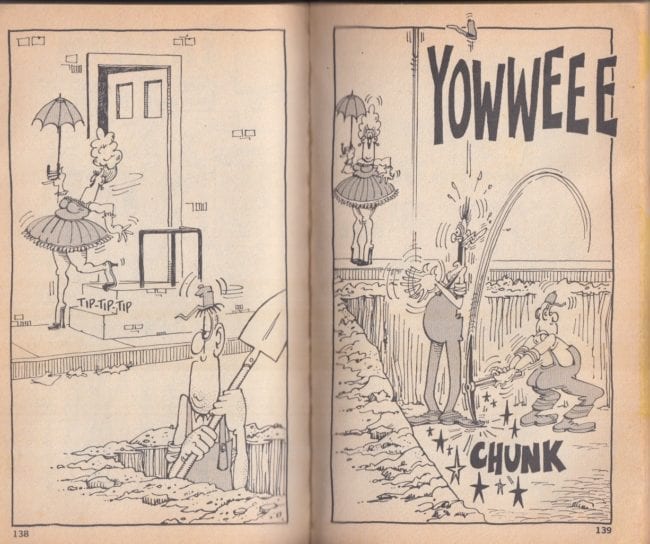

This is creativity and Eisner's "Gerhard Schobble" is the imitation. Comics culture seems to lack the language to define the difference. Burgos has never received his due, but a deserving artist like Don Martin has, in a way. And yet we still don't know exactly how to talk about Martin.

Is Martin simply a wacky goofball who loved to draw 'funny' stuff and use as many sound effects as possible? A meat and potatoes cartoonist who loved to draw people with big silly noses, inflicting comical physical pain on each other? Yeah, of course, and he did that extremely well. But what about the rest of it? What about the meticulous process of taking the world as it is and translating it into a system of drawing that had its own properties and proportions and making that world function on paper seamlessly, so that the jokes would exist on a different plane from reality itself? People love Don Martin without being told to, and I think the admiration people have for his work outshines how people feel about The Spirit on any possible measure. Maybe a healthier comics eco-system would grapple with all of what Martin was up to, rather then falling over itself to assign credit to things that Eisner didn't accomplish but instead suggested that he did.

There is a desire to accept the stated importance of unimaginative art, and believe in the simplicity of works that don't assert themselves. This confusion comes to a head when considering the work of Dave Berg, who even when remembered fondly is assigned a role as a fussy and light satirist of suburban life. To me, Berg's work is far more biting in its critique of yuppie existence in the final fifty years of the 20th century then we've been led to believe. Berg's characters grin with sickening expressions, and hold themselves in extremely uncomfortable and uptight poses. They appear constipated and on the verge of tears even when at rest. Berg doesn't point this out to you, he just draws it, contributing to the emotion of his critique. But as an artist of taste with a true mission beyond self-congratulation, he would never have a character say to another, 'Your face is filled with hate and rage at the life you've chosen!' Eisner or O'Neil would, of course, write those words, and they'd receive the appropriate accolades. Berg just draws it within his unified translation of life into his strips, creating a stifling, deeply scary world. His work chilled me as a child, as it did many others. Martin and Berg used comics to present a vision and a statement, and they didn't necessarily hide it. It's there in plain sight. All it lacks is self-importance, which the comics world seems to need to feel secure in proclaiming something as remarkable.

These attitudes persist today. Comics (again, insecurely) followed Eisner's bombastic lead and embraced the idea of graphic novels as the appropriate medium of expression for cartooning. With this imbedded within them, comics enter the book market in a big way in the early '00s. But cartooning, on this continent at least, lacks the organic history with long-form work that the novel spent a century and a half nurturing as a coherent anchor for a medium now littered with memoir, pop psychology, self-help books, and the flimsy intellectualism of otherwise formulaic pop fiction. Comics immediately ties itself to this terrain as it 'becomes' literature (never mind that it already was and is, just with different, and perhaps opposing, properties). Literature can suffer a handful of fools, because it has a deep history to weather it. Cartooning, given the already shaky self-conception is has, is on more dubious ground as it confronts the general reader and tries to explain itself.

Now, of course, memoir and essay can be done with beauty and wit, in both literature and cartooning. In comics, Maus and Persepolis are worthy of the praise they earn and the genuine admiration they inspire in readers. There is much to love in those books and they are explicitly cartoony, using the medium itself as much as possible. But with their success folded into what bookstores crave, and the hollowness that we've laid out with the likes of Eisner and O'Neil, comics backs itself into a corner, at least publicly: graphic novels aren't space operas... no, they are lightly illustrated representations of tragic events. By deemphasizing the likes of Burgos, Martin, or Berg, and instead asserting the idea of importance rather than the thing itself, we head into choppy waters, guaranteed to yield bizarre creations. Simultaneously, long-gestating works by Doucet, Clowes, and Ware are packaged for bookstores, rejecting Eisner's pap and instead looking inward. But 'serious' cartooning in the public eye asserts itself not as fully in the image of Doucet or Lynda Barry or Deitch as one might assume, given the decades of artistic concentration those artists were involved in. Instead, cartooning in 2018 in the popular imagination is more in the tradition of Eisner than Clowes, as is revealed when we pick up a work like Kristen Radtke's Imagine Wanting Only This.

Imagine Wanting Only This is concerned with an obsession for decay, a tourism of abandoned places. On the face of it, this is a topic that sounds fascinating for cartooning to tackle. And yet we are instead left with merely that idea, not the execution, not a journey with that idea to anywhere remotely coherent.

When I think of this book, I can't get past the way characters feeling are presented. There is so much emoting in this pages, every page has characters staring at us in sadness, anguish, excitement or happiness (which of these emotions we are supposed to come away with in any given scene is, strangely, hard to discern). Yet for all of indication of emotion, there isn't one expression that feels human--and, if that wasn't the intent at all, there isn't a moment that even feels inhuman. Radtke's drawing fits with her limited exploration of decay: the idea that she's 'on to something' is enough. Radtke's book says it's about 'ruined places' and her characters show... some... sort... of... emotion, kinda sorta? With the standards that comics has laid out for itself, that is more than adequate. The book indicates that it is involved in serious things and so it is, officially.

As far as I can tell, Imagine Wanting Only This is Radtke's first long-form work, so the ambition of the project deserves some consideration. Cartooning is complicated and the amount of time Radtke put into the book suggests an artist who may soon bring us something closer to what her work presents itself as. But this is also a piece of art that has received glowing praise in serious literary publications, including The New York Times, which stated that Radtke's drawings 'depict contemporary reality with uncanny precision' and likened her work to 'grandmasters like Adrian Tomine and Chris Ware.' Personally, I don't think either of those people are (ugh) grandmasters, but I do think they are conscious of what they are doing and continue to refine their art, in the earnest attempt to one day become (ick) grandmasters. Confusing Radtke's inchoate expression with the extremely refined (for better or for worse) work of Tomine and Ware indicates a mistake that the regular world often makes when it confronts comics: a graphic novel is successful if it's a simplistic exploration of complexity, and all variations of simplistic execution are equal. That's, according to the standards comics insists on defining for itself, how the world has received this art form. How, then, does an artist like Anke Feuchtenberger fit into all of this?

Feuchtenberger, in my view, makes images that surpass the emotion and ambiguity of Friedlander's photography. She draws solid figures, with a degree of expertise that even those who yearn to dismiss her as artsy experimentation can't diminish. These figures are used to make thoughts by the artist into narrative. Rarely is a back story of the characters offered. The world they inhabit exists not as a real place, but as a stage for them to speak and push against each other so as to express the author's (often in collaboration with Katrin De Vires) heart and mind.

In one book, an entity asks the character W the Whore 'what does your body feel. It will only be shown this way today.' W responds: 'I do not feel the body.'

Here, we have a thought, something for us as readers to consider, something to feel. Sequence, the caricature of the human body into a repeating character, and word balloons (in other words, the simple, non-experimental mechanics of comics) are all used to express this set of phrases and thoughts. A concept of Feuchtenberger and De Vries mind is made into a figure of expression, an honest and comprehensible one, and yet still somehow void of concessions. Comics, as the lucky few know, is an embarrassment of riches when it comes to works like this. Barry, Clowes, and Doucet all practice in this vein alongside Feuchtenberger. However, when presented with Eisner and Radtke, one might assume the task of comics is so complicated that expressing a unique worldview is far too much to ask.

There may be something to that. Simply, (1) drawing competently is an out of the ordinary achievement people instantly recognize. The ability to (2) tell a story with drawing? Even rarer. The most elusive seems to be (3) having something unique to say with a picture story. Most of comics seems to be content with varying combinations of (1) and (2). Artists like Feuchtenberger give us (3) every time they draw something. Why work like hers is considered an aquired taste still seems odd to me, and involves a condescending attitude to readers in general. Who doesn't (if we limit ourselves to those who care about narrative in even the most limited way) want to be engaged by a picture story that is genuinely felt and mindfully arranged? When we consider a masterpiece like Dominique Goblet's Pretending is Lying, which is firmly in the (1) + (2) + (3) camp, we know this is a work that readers will refer to in their lives over and over again. Goblet might simplify faces in service of telling her story within the medium of comics, but to simplify her ideas would be anathema to the artist. The richness of what she has to say is, itself, the point. Her statement, a composition of relationships that fade in an out if view, isn't grafted on to her storytelling ability, it isn't in service of a need to finish pages to fufill a pre-existing belief that her style requires an important statement to validate it. When Goblet's father character sways and monlogues to promote himself, his personality impresses itself upon the reader with a shrieking force, because Goblet has something specific to say (3) about a man like this.

Even a comics story that is modest in scope is made up of hundreds of drawings, thousands of faces rendered in pencil, then redrawn in ink. To tell a story, some simplification may be required. But the works that animate the medium are not the ones that use simplification as an excuse to blight out any complexity hiding in the corners, to etch caricature onto ideas themselves. Instead, the medium proves itself oddly capable when it takes a simplified face and allows it to exist in, and to amplify, a realm of actual thought and feeling. Many of the cartoonists discussed here seem to fall back on a half-belief in cartooning: 'The form is lacking, but I'll impress my mind on it and that will be enough.' Those artists are either in embryo or not worthy of our full attention (yet), despite the pressure that is impressed upon us to consider them. Instead, our hearts go to the artists that bring themselves to cartooning with the outlook of the medium as an equal, as a peer capable of perceiving the most complicated puzzles of the artists and readers lives.