"These Cans" by Joe Decie

Preferences don’t occur in a vacuum. The rules by which we curate our lives are a complex web of past experiences and associations—behind every aesthetic impulse is an emotional one. In his lecture “The Superego and the Act,” Slavoj Žižek suggests indistinguishability “between the object of desire and that which makes me desire the object… [T]he whole point of psychoanalysis is that desire is mediated. It is never: ‘I like strawberry cake.’ Ok, maybe you do but that’s another story. The point is that I like the cake because for example I know that another person that I love likes it and I want to impress them. Desire is in a sense always intersubjective, it is never simply me and the object.” In his one-page comic “These Cans,” Joe Decie depicts the perverse bargain of melancholic desire, whereby an object’s utility is not in its literal use but in its fetishistic function: it signifies desirable feelings and experiences to the user independent of its actual purpose, which is irrelevant.

Every day Decie drinks a can of fortified milk. Ostensibly the only reason for a beverage to exist is that it tastes good or satisfies a nutritional requirement (ideally both), but Decie doesn’t like the taste, and he’s impervious to its purported health benefits. What he does like is the drink’s exotic lineage. He likes its old-fashioned pop-top can. He likes that the drink reminds him of a Tribe Called Quest song. These symbolic qualities of the fortified milk drink are more important to Decie than its material qualities, to the extent that he consumes it—which he doesn’t enjoy—in order to access them. In a sense, the symbolic identity of the object has entirely replaced its literal presence.

It’s a paradox: the thing which exists does not really exist because its material state goes unappreciated; the consumer interacts primarily with the metaphysical idea which has replaced the thing, yet he does this ritualistically, by interfacing with the irrelevant object itself. Decie reinforces this paradox in his artistic choices. His narrative sketch of the drink’s abstract joys is circumspect. He doesn’t tell us what song it reminds him of or why (I decided it’s “God Lives Through”), he doesn’t show us the nostalgic pop-top in action (merely—significantly—the hole described by its absence), or even identify the feeling as nostalgia. Like him, we are unable to access enjoyment by drinking it, but then he also withholds from us the secondary enjoyment of its symbolic power. The illustrations also thwart our attempts at enjoyment. Rather than offering images of himself buying and drinking the drink, or depicting the things of which it reminds him, which we might enjoy vicariously, Decie offers six nearly identical drawings of the object itself. They’re good ink-wash sketches, descriptive of the empty can, shifting aimlessly back and forth, drained of any meaning.

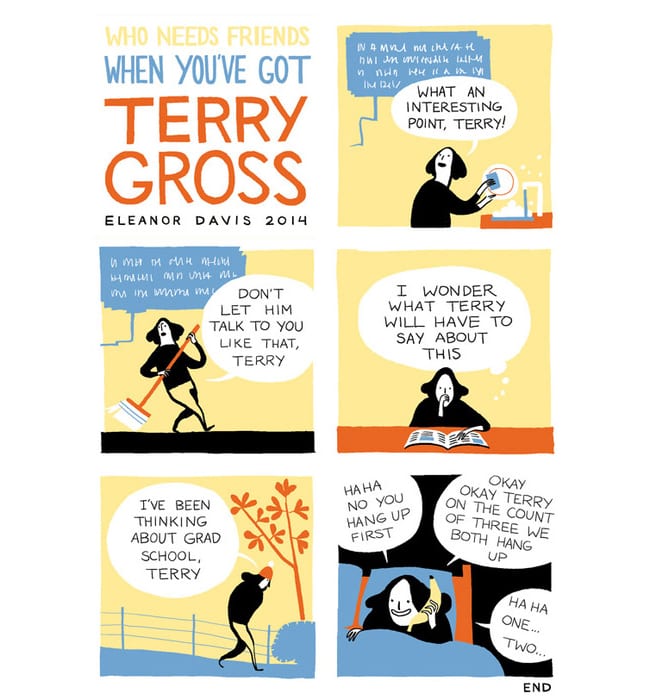

"Who Needs Friends When You've Got Terry Gross?" by Eleanor Davis

The psyche requires an "other," the hypothetical imaginary friend to whom we address dialogues we cannot entrust to actual people in our lives. Often this other takes the form of an idealized version of a person close to us (we imagine a loved one holding our hand during a difficult medical procedure), or even someone we dislike (we visualize delivering the tirade an unscrupulous friend deserves, and enjoy imagining that person's reaction) and we withhold the pursuit of the experience in reality because we know it cannot produce more satisfaction than its counterpart in fantasy. In fact the task of reconciling our actual relationships against the projected desires with which we mentally conflate them can be aversive, leading us to dodge true intimacy lest actual events somehow contradict a more comfortable constructed narrative. Essentially this is the question posed in the very first panel of Eleanor Davis's comic for The New Yorker: Who needs friends when you have Terry Gross?

Terry Gross, the warm and incisive host of NPR's long-running Fresh Air, is in many ways an ideal other. A skilled and celebrated interviewer, Gross, in her public life, has one job: to be engaged with, informed on, and curious about other people. As we know her, her entire being is summed up in the task of being fascinated by someone else and making them look good--to paraphrase Virginia Woolf, Gross's magical power is reflecting her guests at twice their actual size. How thrilling, then, to imagine her turning this magnifying beam of insight onto ourselves. And more thrilling still, to upend the dynamic, to be the person to whom Gross herself turns for support and understanding. Our minds aren't equipped for the modern innovation of knowing people who don't know us; the flush of pride and affection when a familiar celebrity does something familiarly brilliant demands a commensurate friendly response.

The main character of Davis's one-page comic starts out listening to Fresh Air while she does housework. Gross's words are indistinct, the chill droning mechanism of the radio implied by the sharp blue rectangle that contains them, oblivious to the woman's amiable responses: "What an interesting point, Terry!" and "Don't let him talk to you like that, Terry" (maybe she means Bill O'Reilly). The woman reads a magazine and anticipates Gross's reaction to it, then she imagines seeking Gross's advice about her own life--the artifice of the imaginary friend becomes more absurd the more it responds to the specific needs of the person imagining. By the end of the comic she's talking to a banana, pretending it's a phone, the disembodied voice has taken on a life of its own, and in the fantasy Gross is enjoying their conversation as much as she does, neither wants to hang up. This looks like lighthearted lunacy, but it's also the logical continuation of the emotional process of inviting an imaginary "other" into our life as a friend.

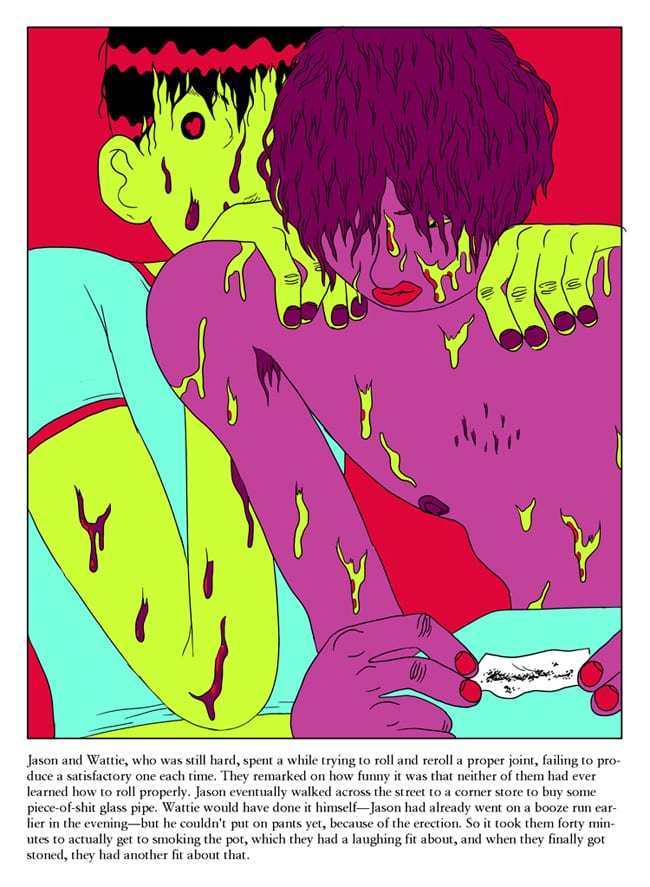

"Actual Trouble" by Michael DeForge

The phallus, as distinct from a mere erect penis, is an unattainable object embodying desire itself, the fantasy of perfect satisfaction. In its state of perpetual alacrity, it also presents a kind of demand: the imperative to pursue and enjoy. But this quest can have no end--the phallus is a mirage camouflaging a fundamental lack, for in reality there exists no ultimate enjoyment to quell once and for all the longing for further enjoyment. The only option that remains is to derive some fleeting pleasure from the illusion itself.

An unwinnable quest for satisfaction is at the heart of Michael DeForge's "Actual Trouble," so it's fitting that a priapic lover takes center stage, superhuman resilience elevating his erection to the mythic "phallus" status. The comic is dense with more subtle phallic imagery too--a pencil, a piece of chalk, a throbbing hand, a lit joint, and even a shuddering auroral curtain seem to jut into the panel at eager 45-degree angles. Like the physiological state they evoke, the potency of these objects is more promise than fulfillment. When a character does manage to wield a phallic symbol, it behaves unpredictably, paired with text betraying the farce the image had concealed: the exams conquered by the pencil are "antiquated and arbitrary;" as Jason, the narrator, holds up the authoritative chalk he realizes with disappointment that his stable teaching job has replaced a stable love life.

Yet in spite of the failure of these secondary phalli, the centerpiece of the comic, the erection sported by Jason's boyfriend Wattie, never wavers. Apparently eternal, it begins before the first panel and continues beyond its end, and the story's gentle chronological shifts reinforce the sense that the phallus exists simultaneously at all points in time. Though initially baffled by the intrusion of this powerful thing into their lives, Jason and Wattie soon shape themselves to accommodate it, attempting to meet its implicit demand with ever-broadening adventures in sexual and chemical experimentation. Of course these attempts fail, of course eventually the only thing holding both men together is a tacit agreement to pretend the erection is conquerable, to keep trying. A different satisfaction emerges in the last panel, as Jason muses that the quest has been a reward in itself, and it's to DeForge's credit that he only lingers on this hackneyed observation—"the journey is the destination"—long enough to leave us ill at ease.

A young student, who looks like Jason's double with the same chartreuse skin and red-glinting eye, never gets to smoke the joint he brought to class, but as the narration explains, that foregone pleasure is the price the kid pays to escape the implied threat of the title. In fact the confiscated weed is a source of bemused frustration to Jason and Wattie--neither of them can roll a practicable joint, so the weed is transferred from a phallic cigarette to a "piece-of-shit glass pipe." Jason is reminded of the weed he smoked in high school, trying "to suck whatever buzz they could out of some limp, loose thing." Even the high it produces is disorienting and melancholy. They achieve the consummation Jason's student missed out on, and with it they get the "actual trouble": the disappointment of realized desire.

Julia Gfrörer is an elderly beggar woman who practices the divinatory arts in exchange for crusts of bread and kisses from comely youths. See more of her work at www.thorazos.net, or follow the Symbol Reader blog.