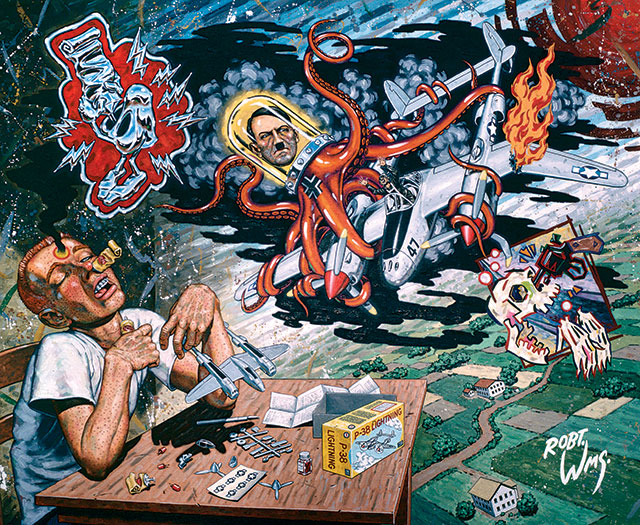

For thirty years, I’ve had a special affection for the paintings of Robert Williams. It started when I saw his “Patrick Has a Glue Dream” and found myself laughing happily. An all-American freckle-faced kid nodding out with a tube of airplane glue stuck up his nose . . . a hallucinatory vision of Adolf Hitler’s head in a glowing yellow bell jar, attached to a giant red flying octopus . . . scarlet tentacles crushing a Lockheed P-38 Lightning above a placid European countryside . . . how could anyone not laugh at the glorious incongruity, the perverse collision between 1950s suburban childhood and the Third Reich? I have a framed print of it hanging on the wall opposite my desk, and it still makes me smile.

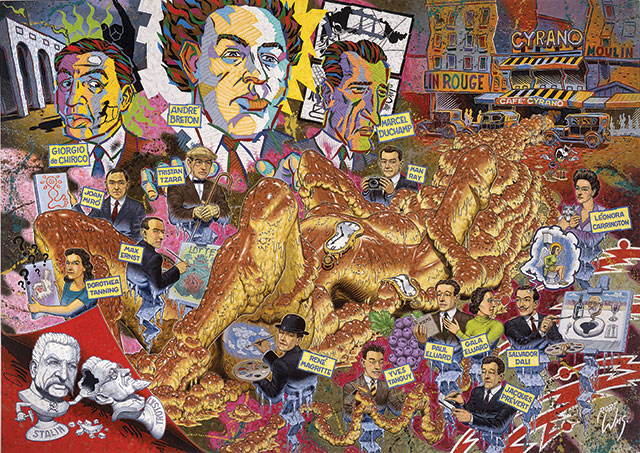

On the opposite wall hangs another Williams print. “The Mirage of Daughterly Fears” depicts a sleeping teenage girl clutching her teddy bear, dreaming of a naked skeletal mutant doctor using forceps and an electric drill to torture a dream-copy of her bear, which has been clamped in a framework of steel rods. The doctor has multiple yellow eyeballs, a nose like a beak, decaying teeth, and hairy green buttocks, with tan lines. One foot is necrotic while the other has a big toe that looks like a giant hairy testicle. The doctor is being attacked by eyeless four-legged purple blobs with claws and hideous fangs, racing out from the girl’s subconscious to defend her bear. In the background is a serene desert landscape out of Salvador Dali.

The sight of a Williams painting generates a flood of endorphins in my brain, as if I am being welcomed to a refuge from reality where, in the words of William Burroughs, writing about the Interzone: “Nothing is forbidden. Everything is permitted.” Yet over the years I have learned that not everyone shares my delight when viewing paintings such as these.

More often than not, when I receive a visitor, there will be a Bad Williams Moment. The person walks around my office, checks the shelves of books, admires the view from the window, and then, inevitably, sees one of the framed prints. A moment of confused silence ensues as the viewer pauses—hesitates—steps closer—and then steps back. Next comes the shocked look, almost a look of betrayal, as if the person feels like a victim of a practical joke. And the inevitable question, in a querulous tone: “What is that?”

So I have to wonder: Why doesn’t everyone laugh happily at the sight of “Patrick Has a Glue Dream”?

This was a primary question in my mind when I visited Robert Williams at his home in the greater Los Angeles area.

The exterior of the house allows no clue regarding the singular nature of its resident. It looks no different from the other conventional ranch-style houses on the block. Inside, however, this is not a family home. The living room and most of the bedrooms have been repurposed. I find a spacious studio filled with recent canvases, while Williams’ wife, Suzanne, uses another room as her own studio. In a windowless room, behind protective glass, is an amazing collection of German military helmets from 1842 to 1918. In the garage are a 1934 Ford, a 1957 T-Bird, and a 1932 roadster, all immaculate.

Williams welcomes me into a small library, the shelves densely stocked with art books. He’s an affable man, but has little time for pleasantries. He’s ready to get down to business.

I ask him why he is taking the time for this interview. “Oh, to extend my legend,” he says, with a twisted smile. “Although at this point, extending my legend is like trying to stretch a prophylactic over the mouth of a mason jar.”

By mixing 1950s vocabulary, a quasi-sexual metaphor, and self-deprecating humor (which I think is usually a cover for humorless ambition), this casual remark actually serves as a good preface to Williams’ work.

As I set up my digital recorder I mention that I have brought with me a list of key words that I compiled after leafing through my books of his paintings. The list is my summary of his iconography. I’m hoping to use the words as a starting point for conversation—but he’s in no mood for a discursive chat. “Show me the list!” he demands.

And so the first part of the interview becomes a monologue, as he takes control of the list and interviews himself.

Devils

“I’m really fascinated with devils because it’s such an old symbolic figure. When I try to find a better persona of evil, it never seems to come out quite as good as just outright devils. Lizard people, snake people, cyclopses, obvious criminals, symbolic murderers—devils seem to work best.

“My work has to make references that people understand. It doesn’t take much to lose your audience. I’d rather come up with my own original idea for a persona of evil, but the devil reads real quick.”

Jesus

“Some religious people came in and wanted to talk to me. Said ‘We feel that you have ill-represented our savior Jesus Christ.’ I said, I’m not a person necessarily of a religious persuasion. But I’ll tell you, if Christ was hear today, he would not want to be represented as a naked man nailed to lumber. That shut ’em up.”

Dangerous Beautiful Women.

“If women didn’t have certain sexual attributes, they would have been eaten long ago. That’s exactly right. Now, I don’t want to be sexist, and I’ve got an intelligent wife, and I really respect women. I’ve got the greatest joys of all my life from women. I am a slave to beauty, and a beautiful woman has an enormous influence on me. I have known dirty fuckin’ whores who have taken me to the cleaners and worked me over and tried to pull me into their web. I had to talk my way out of fighting a golden gloves champion one time because his blonde girlfriend got after me. I’m attracted to really beautiful women, I know it’s a weakness, and I’m very careful of it. I can imagine how dangerous some women can really be, and be that way purposely.

“You know where the name ‘California’ comes from? I used to think it came from the Mexican land owners, the Californios. No. A famous Spanish writer—I can’t remember his name—he claimed that on Baja, there was a tribe of lesbian cannibal amazons. And they raised men for food and sex. And they had an enormous stash of gold, and the queen of these amazon lesbian cannibals was a gal named Califa. You look on the side of a cop car, and there’s fuckin’ Califa, this figure that looks like a Greek goddess. The lesbian cannibal amazon. That’s dangerous women.”

Nurses

“The female that takes care of you. The Florence Nightingale we all want. We all want a fuckin’ nurse.”

Bondage

“It’s interesting as a statement in paintings, and it is in my work, but my opinion is, I have been arrested and manacled enough to know there is no way I could get a sexual charge out of being handcuffed or tied up. I’ve been under some rough cops that have thrown me in jail. So that ain’t in my repertoire.”

Women Smoking Cigarettes

“For the last 150 years cigarettes have been a sign of dissipation and indulgence, especially with women. It means they fuck. In 1880s tintypes, if that girl’s got a cigarette in her mouth, which was very rare, it meant she was a woman of evil. It’s unfortunate the way they persecute people over cigarettes, but society has to pick on something.”

Helpless Children

“This is simply me violating social mores. Children are so defenseless. Everyone’s always defending the babies. I’ve done stuff that suggested child pornography, and I’ve had the FBI on me, trying to set me up with kids calling and asking me to have sex. But the last thing I would touch is a fuckin’ child. I can’t stand children. I don’t like being around children. The idea of having sex with children is abhorrent to me.

“I’ve got little cousins who I try to be nice to, but I don’t want to touch ’em. They’ve got germs, they’re human beings in larva stage. Like a bug. Me and Suzanne don’t want children, because we are children. We’re each other’s child, and we cannot be responsible for raising someone up and have to take of ’em, and they may not like us, and—you know. If I’ve painted children with warmth or sympathy, it’s only because I needed to create that impression in that particular painting.

“The vast majority of witchcraft trials were based on acts against children, and children’s testimony. Just like they’re harping about child pornography now. I had a friend who liked photographs of kids fucking, and now he’s doing four years in a federal prison. I think children should be left alone, but it’s the same hysteria, going on now, that there has always been about using children. They’re easy to use. I know people in Spain who fuck their children. I know intelligent people in literature and the arts who fuck their children. I think it’s disgusting. I hate to think about it.”

Pathetic Men

“All my pathetic men generally have suits on. Though I wear a tie and a sport jacket, I hated ties and I hated men in suits because they were very oppressive to me as a young person. Conforming Anglo males—I couldn’t stand them. I’d see a guy and his buddies, and they watched the football game and the big-titted cheerleaders, and drank the booze and ate the chips—they were fuckin’ pathetic to me. Fuckin’ incapable of an original thought. Sit down and talk to them, about the girl at Hooters with big tits or the car wreck down the road, what the baseball scores are—there’s a giant world of abstract thinking, they can’t do it, because they regulate it out.

“I grew up under these people’s hands. Authorities at school, people I worked for. I worked for some real right-wing companies. And the salesmen and executives, these masculine people had all this pride and anger and anxiety and jealousy. Incapable of free outward thinking.

“My dad was very conservative. He had an imagination that was ready to explode, but he couldn’t let it, because he believed in the scriptures and whatnot.

“Portraying these guys as chumps is my petty revenge.”

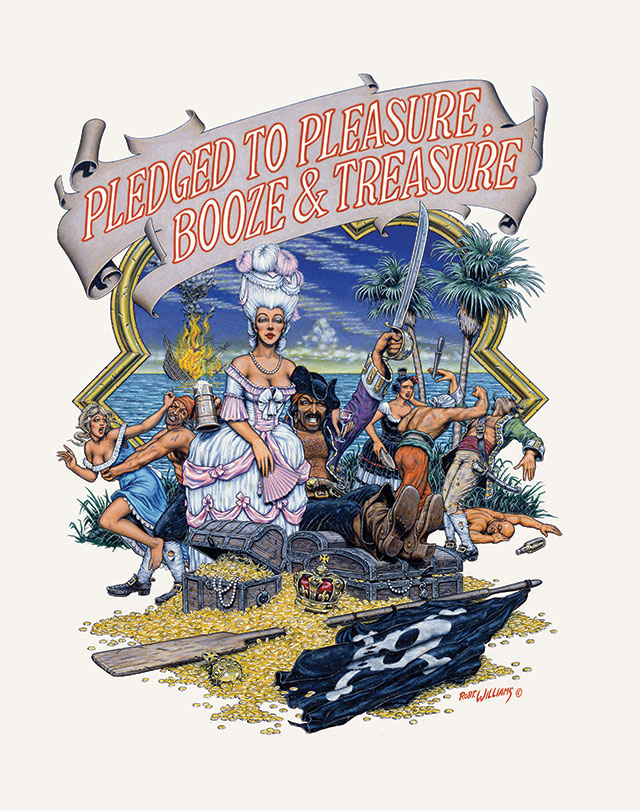

Pirates

“Right now, I am fascinated by Somalian pirates. Where do these guys party, where do they drink, what kind of women do they have, what’s their philosophy, when they go out and bring ships in, who would they kill and wouldn’t kill, what kind of hostages would they take, and how would they treat them. It’s really interesting. It’s a syndrome that goes back hundreds of years.

“In 1840s and 1850s, cowboys were people who worked cattle in the Southwest. They dressed like farmers, but some of them picked up some style from Mexican vaqueros. The boots, the sombreros. But they were slovenly. Most of them just had big straw hats like farmers.

“In about 1880 or 1890, writers started doing dime novels. These were people from New York, making up style for the cowboys. Then before the First World War, there were cowboy suits. It had nothing to do with anyone who worked cattle. Asinine clothing. I was raised on a farm, and had to work cattle.

“After World War 1, into the forties, the cowboy suits got baroque and rococo. They got fuckin’ ridiculous. So ridiculous, Salvador Dali would wear a cowboy shirt. That’s what’s going to happen with the Somalian pirates. It’s happening with bikers now. Bikers back in the forties were just slovenly guys who rode motorcycles. Now it’s a fuckin’ hip style. You see bankers on the weekends, dressed like bikers, with colors on and shit. I could go on and on about costumes and stuff.”

Gorillas

“Gorillas are interesting, because they’re our cousins, and they’re very, very powerful. They’ve only been known for about 150 years. They’re remarkable fuckin’ animals. They symbolize the true monster. I find chimpanzees a lot worse, because they’re a lot closer to us. They’re extremely intelligent and evil. They have greed and jealousy, and they’ll tear you apart. They kill each other and eat each other. They are the closest living thing to us. When you’re looking at a chimpanzee, you’re looking back in time at our asshole ancestors.”

Monsters

“Monsters are the fantasy anthropomorphic creatures that you make up in your head, that you’re attracted to. I love cheap B movies with goofy guys in costumes. I love monsters, and apparently everyone has through history. It’s widely shared, goes back to minotaurs and centaurs and cyclops. It’s a good fascination point. I think we’ve run dry on zombies, vampires, and werewolves. Monsters are fun. And when we had underground comics, we could make them do the nasty things we presumed they would do but had never been revealed.”

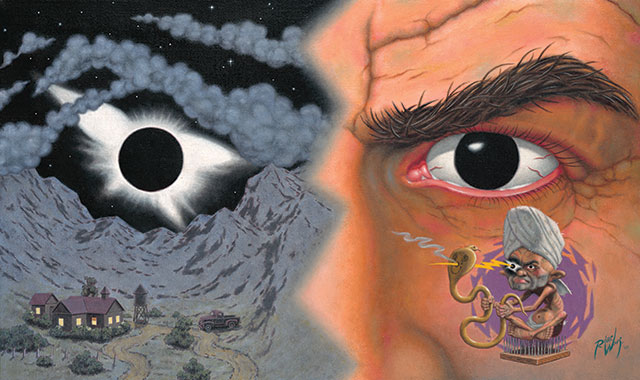

Eyeballs

“They’re obvious. They go back to An Andalusian Dog with Dali. One thing you learn early in life is to notice if something is looking at you. You can identify the eyes right off. That’s why they’re on butterfly wings and all kinds of other stuff. Eyeballs are almost as powerful, visually, as sexual organs. A girl getting your attention, or a guy who doesn’t like you, or a policeman sees you—you know instinctively when people are looking at you.”

Fatal Accidents

“In the last 150 years it has been presumed that paintings should be docile and innocuous and calming. But I consider graphic art should be on a par with literature. If you’ve got a coffee table with books on it, let’s say you’ve got Moby Dick. And A Tale of Two Cities. War and Peace. But you can’t open those books up and show their contents as pictures on a wall, because people would shit their pants. So art will always be shoved down way below literature, as a language. Literature can say a lot. Paintings have got be calming. Art gets an immediate response. That’s why people do timid stuff, like portraits of their mother.”

Blood

“When I see blood I just pass out. I’m a pantywaist. I have a range as a painter, from innocuous flower painting to scenes on a battlefield, infantry spilling their guts over no man’s land. But in real life, if there’s an auto accident—I’ll pass out if I see a bunch of people laying dead on the street.”

Weapons

“It’s fun to shoot guns, you know? Me and Suzanne have a number of guns, they’re antique, interesting guns. I’ve never seen an ex-cop that didn’t have a gun. I’m not a big proponent of the constabulary but I can see why they would carry guns.”

Dead Animals

“A dead dog is a euphemism for gruesome garbage. Dead dogs for me are a euphemism for something worse than garbage. However, I have a philosophy that if you want to sell a painting, put a dog in it. A live one, I mean.”

Sensitivity

“I have too much. It festers in me.”

Ugly Old Buildings

“They’re just like looking at a skeleton of something dead. You see an old house, you think, this place could talk, man. You go to Europe and see those really old fuckin’ places, Roman ruins and stuff—you can just see the ghosts coming off of these things. Eighty percent of people can’t comprehend that. Most people are very linear. It gets them through life. I’m real fucked up because I’m subjective. I’m left-handed, I’ve got the wrong side of my head, everything’s a mushy emotional experience for me. Most people are objective and real fuckin’ linear. We function in a very linear world that keeps us in wars all the time. Cause-and-effect, left-brain kind of thing.”

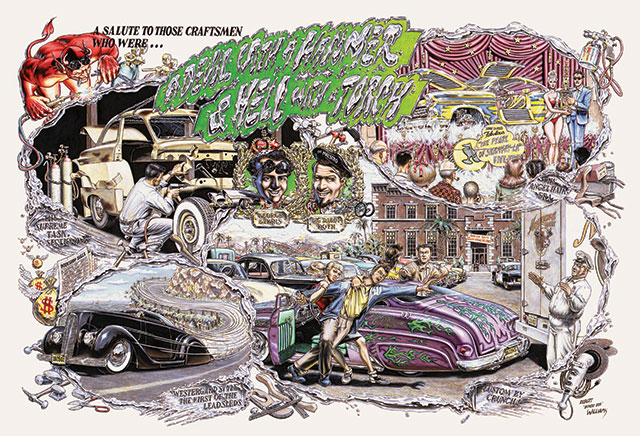

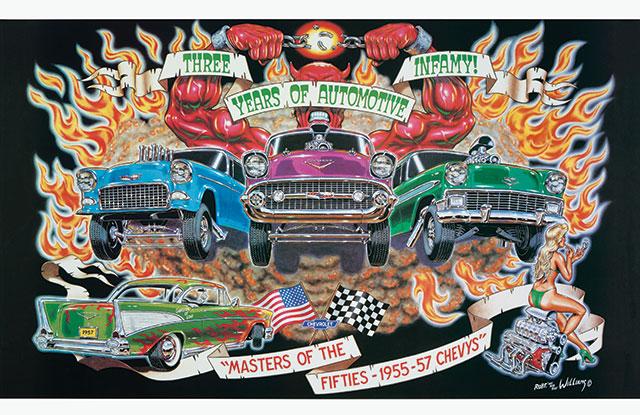

Cars

“My mechanical male thing. One girl told me it’s an extension of my dick. I have a thing about cars that I have tried on a number of occasions to get away from, and I keep going back to it. There is a romance, a mechanical maleness, a thrill.

“I’ve always been a hot-rodder, and when I was young, in the fifties, we had primer-painted beat-up hot rods that were junk. As hot-rodding evolved, it got more sophisticated, and no one had primered cars anymore. So I got a ’32 Ford roadster, I just wanted a beat-up hot rod like back in the fifties. When they’re primered they look like they still have potential. People will say, what color are you going to paint that?

“When I took my primered hot-rod to a car show, they wouldn’t let me in. So I started this thing called rat-rods. There’s now hundreds of thousands of rat-rods. They’re big in Europe. They’re big in England. In Japan. But nobody remembers me.

“Same thing in the art movement, with my fuckin’ sacrifice. Decades and decades of eating shit and laying on the barbed wire while these clowns ballet across my back. That’s the way the world works, and always has. Like the guys who started surrealism, at big cost to themselves, and here comes Salvador Dali dancing along, and now when you think about surrealism you think of Salvator Dali. But that asshole had only a little bit to do with surrealism.

“Artie Shaw, the big-band leader, said, ‘Never be first.’ The idiots are the first ones.

“Actually I’m a very big admirer of Dali. He was great up till the late thirties and then he started making an enormous amount of money and realized how he could keep making that money, and his work, as slick as it was, started becoming calculated, for his audience. From when he started, till about 1938, he did the most flipped out art in the world, and then he started having other people do the work, started using photography, you know? I’ve been to Figueroa in Spain and seen his work. He must have had a crew working on those big paintings at the end of his life, seeing that he was spending half of each year at the St. Regis Hotel in New York.”

Williams has exhausted my list of keywords. He sets it aside and takes me into his studio. Dominating the space is one large painting crammed with an amazing density of detail. He says it has taken him eight or ten months to complete, working seven days a week. Soon it will be on its way to the Tony Shafrazi gallery in New York.

I ask to what extent he plans each painting.

“Each painting has been totally figured out. I do a large number of sketches before it’s transferred onto the canvas.”

He begins painting in red, emulating the sketched outlines. “Then I do three layers, trying to get the color right. In the end it looks airbrushed, but it’s not. If you look closely, the original red shows through in some places, although you don’t notice it, because it’s red.”

Does he have paintings that get out of control, and are never exactly what he wants?

“Every one of them. Every one is a child that needs discipline.”

Does he ever reach the point where he has to give up on a painting?

“No, I just keep working and reworking.”

Is it fun for him to be in his studio, painting?

“Well—it’s a lot of hard work. Fun wouldn’t be the right word. I’ve done an enormous body of work because I disciplined myself. I was turning out an art show of 30 paintings every 18 months, like a machine, working 100 hours a week. A painting machine. I’d get up at 4:20 in the morning and work till sundown. I’d take uppers and whatever it took to keep me working. And one day I broke down. And Suzanne said, ‘You ain’t doing this to yourself, this is over.’ This crazy work thing that I’d done for decades. Young people fly by me, now, but so what. I try to make up for the loss of production by how wild the ideas are.”

He has 26 paintings in his studio, waiting to go out to his next show.

“Well, I’m still always working, but slow now.”

So, despite being a lifelong rebel, he has discipline.

“Yes, discipline gets things done. I’m weak in so many ways, discipline is a crutch. I work every day, seven days a week, because if I don’t work, that Protestant guilt is going to start working on me, because I’ve got to produce.”

And what happens when he’s sick, and can’t produce?

“I grieve. I have to get well within the next couple of days and get back to what I’m doing.”

What if he lost the use of his hands for a significant period?

“That would kill me. I had a hand go gamey on me one time, but usually it’s been just flu or cold, kidney stones. But I had to have two stents put in my chest, had to lose a lot of weight. I still like my bourbon. That’s my last vice.”

Is his self-discipline also driven by insecurity?

He nods. “I’m insecure.”

But he seems to have a strong sense of identity.

“Looking at me, I can see what you’d think, but that’s a facade I’d like to present to you. In my world, I’m almost under the tractor wheels, one step from this thing that’s going to grind over me.”

I ask him about his technique, using black outlines to differentiate figures from background. Comic-book art is entirely done with outlines. They were rare in western art, but van Gogh used them, and they are fundamental in Japanese wood-block prints.

“Well, van Gogh was a cartoonist. If he had been alive in the 1960s, in Amsterdam, he’d have been an underground cartoonist.

“But you also find outlines used by manuscript illuminators in the middle ages. And look at the fuckin’ Lascaux cave paintings, 35,000 years ago. Those are cartoons. And I would go so far as to say I think they did preliminary drawings. I think those things were worked out on skins. Those guys were struggling, making visual medicine. That was hoodoo on the walls. I’m sure they worked it out with charcoal on a skin.

“When you’re an artist, you know these things. You know that Michaelangelo couldn’t do that whole fuckin’ Sistine Chapel. You know that! He did the drawings and then he had people get up there and paint it. Then he’d go up there and touch it up with dark and light tints. All artists have employed underlings.”

Back in his library, we start going through some of his books—especially Malicious Resplendence, the biggest collection, published in 1997 by Fantagraphics. When I mention that the title has always puzzled me, he seems amazed.

“But it’s so obvious! There’s something attractive and dashing and pretty—but it’s malicious. Resplendence is a military term. Resplendent uniform, dress uniform.”

To me, it makes me think of royalty.

“Well you’re right there, too. But there are words that the art world doesn’t deal with. One of them is resplendent. Another word is bitchin’. The art world is a fussy fuckin’ world that keeps themselves closed off. Like they won’t call sculptures statues. It’s just not in their vocabulary. They think a statue is something old. And no artist uses an easel anymore. You can’t find artists using easels. That’s over.”

As we page through his book, I remark that the style of his work is remarkably consistent. This is intended as a compliment, but it triggers a prickly response.

As we page through his book, I remark that the style of his work is remarkably consistent. This is intended as a compliment, but it triggers a prickly response.

“If you line up all of my work, you won’t find any repetition. It’s always different, always coming up with a whole different idea. Look, I’ve got the Picasso book up there, and there’s so fuckin’ much repetition in there, you can’t stand it. See, after an artist tastes success, he starts to react to what’s successful. But I don’t want to follow one thing. Like I started devil girls, and some people have made careers out of fuckin’ devil girls. What the fuck? And I’m the guy who started all the chrome art. You know? I started it.”

His chrome art pushed the boundaries of representational art by straining the ability of the eye to see what was really there.

“It was meant to do that. It made you investigate. I like people to investigate. I used a system of sketches to keep from being confused. It was neurotic, but it was meant to be.”

On page 170 of Malicious Resplendence we find “In Praise of a Psychoactive Hormonal Imbalance,” where two steroid-enhanced wrestlers struggle against a background of an axe-wielding figure being chopped in half with a chain saw. I remark that it’s not a cheerful view of the world.

“No, but this painting has got more energy than ten video games. Anytime you feel depressed, just take a look at this and it will charge you right up.”

We move on to “The Anti-Madonna’s Affirmation of the Status Quo.”

“The person who bought this painting was a movie producer and director of bad B movies. He was living in an apartment behind a store front on Fairfax Avenue. One night he was coming home, and the police stopped him in an alley near his home. He had a gun with him, but he diverted their attention, ran into his apartment, and threw it under the couch. They went in and dragged him back outside, then searched the house, for an hour and a half, before they left. He went back into the apartment, and he asked his girlfriend what were the cops doing here for so long, and she said, ‘looking at that painting’.”

I note that I see fear as a recurring emotion in his work.

“Yes, I think there is a lot of fear in my paintings. I was always intrigued by pulp magazine covers, because they had so much fear in them. Like late Renaissance paintings that were always over-dramatic, done in dark colors, and show violence, impending doom. I’ve always been attracted to that. Harsh shadows.

“I’m very paranoid. I’m always trying to open myself up, drive hot-rods, fraternize with people that were in some respects quite dangerous, trying to enjoy life at a much larger scale than someone who would go to vacation bible school. But it’s a continuous struggle to be extrovert. I’m not naturally that overt. I can be with good friends and booze, but I’m very careful who I’m around.”

I also see a lot of alienation.

“I have always been alienated. I was born prematurely with lung problems. My father was enormously military and he shoved me at a very early age into a very strict military school, which will just traumatize a young person into doing what they want. Then I got into regular school and realized that because I was left-handed and dyslexic and had learning problems, and bad lungs, and I was always falling behind, I couldn’t understand this or that—the only thing I could do was draw.

“I was not good at athletics, I was always out of step, always a fuck-up. Always a fuck-up. The only thing that saved me was the ability to draw. I was fortunate in that respect. Otherwise I could have really had a loser fuckin’ life.”

As an alienated teenager, he gravitated toward other misfits.

“Remember, in the fifties, if you smoked dope, you got it from a guy who was in some burglary heist two nights before. So I was always right on the borderline of trouble. I hated criminals, but the only time I could find some imagination was in a guy who just robbed a fuckin’ liquor store. I was always in bad company with these guys.”

His art is heavily populated with 1950s iconography, but he feels no nostalgia for the period.

“The fifties were fucked. The only virtue I saw in the fifties was that you could get good old car bodies. Early car bodies. Most of the girls would not fuck, and the girls that would fuck, fucked everybody. I was in fights, and trouble with the police, and there was this narrow-mindedness—the fifties were not a pleasant place for me.”

He moved to California to be in art school, anticipating a more open-minded environment.

“I thought I was going to be with these wild people—and then realized they were like Prussian grenadiers or Bible salesmen or something. These people were more conformist than anything I had ever seen. They were like a school of fish looking for a direction. A big herd going whichever way they think the group’s going to go.

“The arts of antiquity excited me a lot, but remember, my developing period was after the second world war, when abstract impressionism had completely taken over. So when I went to art school, I was in for a horrible shock. I had a real interest in hot-rod art, all this stimulating lurid stuff. Comics in the 1950s had been an enormous influence on me, showing me that there were people out there with overt imaginations and the talent to express themselves, and they dared to do it. And it was on the plane of the general public. I was also interested in pulp magazine covers, B-movies, monster movies, you couldn’t get salacious enough for me when I was a kid. I just ate it up.

“I thought that’s what art was. These people could draw good! Their lurid, colorful, outstanding imaginations excited me.”

At the same time, there was a serious subtext to his love for commercial art. It was the last refuge for artistic realism.

“Realism in art, with the exception of surrealism, had burned itself out completely. It had over-extended itself with sentimental tripe. Surrealism was the only banner of realism still standing, and Madison Avenue quickly defiled that, using it up, taking the superficial elements.

“Art academies in Europe 110 years ago were enormously strict, and you had to pass entrance requirements, and a lot of people just couldn’t make it. It was enormously disciplined. But after the second world war, people discovered that if you get really sloppy with art, then everyone can be an artist. Open the door way big, and let all those sensitive liberal people see themselves as expressing themselves, the audience is ten or twenty times bigger than it would be academically.

“After a couple of generations of students getting Bachelors of Fine Arts out of this philosophy, they become teachers. So we’re going on four or five generations now of people who took a great deal of pride in being fuckin’ helpless.

“The only thing that really challenged these people from the late fifties to early sixties was pop art. But pop art was appropriation. So your imagination was kind of dull there, too. You just grabbed something and did it real big. Find some common item and say it was a ‘reflection of your culture.’ They had the intelligence to see that if you want a giant audience, get the most referenceable shit you can find.”

Realistic drawing and painting requires the meticulous rendering of solid objects within a two-dimensional frame—the process known as draughtsmanship.

“The thing I prided myself in most was draughtsmanship. But that was treated like someone trying to win a blue ribbon at a fair, for an egg recipe or something. I worshipped Wallace Wood, and that was the antithesis of art at the time. Really slick, stylized, well-trained art was hated.

“I kept thinking—I’ll keep advancing and there will be a place for me, but the higher I got, the shittier the art got. It was an enormous disappointment for me. This was when I really faced up to the fact that what I am interested in, what I aspire to, the talents I look for, the disciplines I look for, are absolutely against the code of ethics of modern art.”

The steps in Williams’ career after art school have been well documented, beginning with his hot-rod drawings for Big Daddy Roth.

“I was the art director for Roth. It was lowbrow culture, and I had to cater to the audience I was asked to take care of, but I had a freer hand than I’d ever had in my life. I did some pretty wild stuff. All my friends who were painters were fuckin’ abstract expressionists. They referred to me as ‘the illustrator.’ In other words, I shouldn’t try to be in fine arts, I should just do fuckin’ illustration.”

And he was still potentially on the wrong side of the law.

“Roth was investigated because they thought he was connected with the Hell’s Angels. They could never get a thing on him, because he wasn’t involved; they just thought he was. But they also investigated everyone who worked there. They were tapping Roth’s phones, and they had people down the street with binoculars.”

And he still felt vulnerable as he started drawing for underground comix.

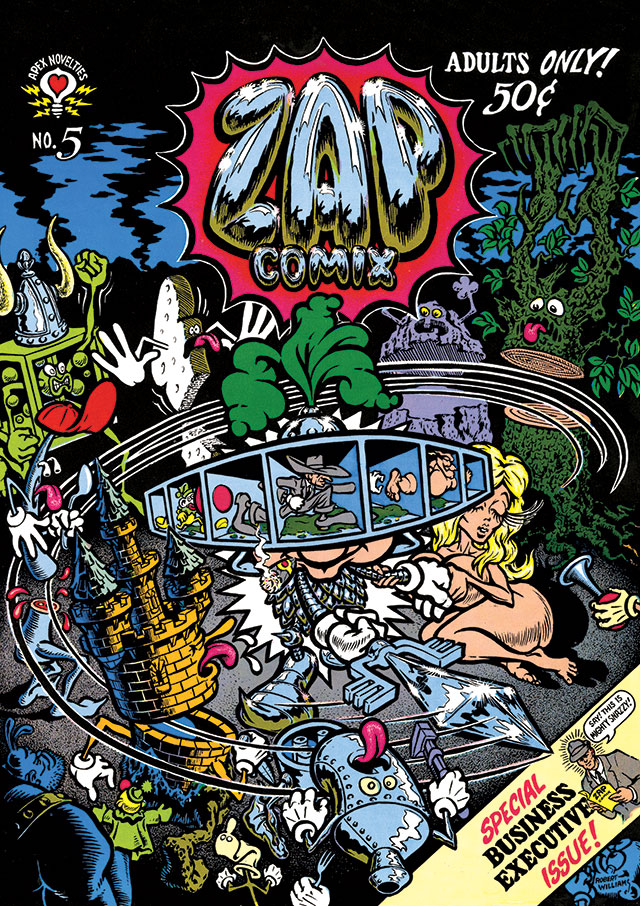

“There was a time in that period when if support for the Vietnam war had increased, they would have started rounding up dissidents—and I was a dissident. Robert Crumb, all the people in Zap, they were out-and-out leftists and communists, so we were in a very precarious situation. But fortunately the whole country swung to the left and got us out of the war. It had been looking, there, for a time, as if they were going to start rounding up people and maybe reconditioning the Japanese internment camps for us.”

Among the Zap Comix artists, Williams finally found a feeling of community.

“All of us had experienced EC Comics, and loved them. And all of us went to art school. All of us faced abstract expressionist persecution. All of us were talented and could draw. So when we found each other, we found a real brotherhood. They were my first peer group. We all hated the government, hated the war, hated the police. And we all liked drugs. We were true fuckin’ bohemians, and it wasn’t an act. It was just wonderful. Later there would be some mild resentments among the Zap Comix artists, which were unfortunate. But we all kept in touch.”

One of the artists Williams felt especially close to was S. Clay Wilson. Robert Crumb once described Wilson as an unpleasant person, but having hung out with criminals, Williams had a tolerance for that kind of thing.

“He was nasty, but enormously intelligent. Me and him were very close friends for a long long time. He was very well read. He would talk in colloquial vulgarity, but he was intellectual. If you had talked to him, he would have really impressed you. He was always picking things out of history to relate to. And he opened up underground comics. If not for S. Clay Wilson, Crumb would still be doing happy-animal shit. Like Fritz the Cat. Wilson changed Crumb. He changed us all. Before he came along, we wouldn’t dare do what he did.”

Although Williams used to hang out with the artists in San Francisco when he could, he was still living in Los Angeles.

“Rick Griffin was down here too, some of the time, and he would go off on these mystic soul journeys. They couldn’t find him to do Zap. He would be off on one of his apparitional pursuits, you know? So they took me, I was a slick artist, they needed a slick artist to fill his shoes. Gilbert Shelton got me in. He was in the hot-rod world too. He was doing stuff for drag-racing cartoons.”

Drawing for comics encouraged a new kind of narrative thinking.

“Underground comics brought out the desire in me to talk, to narrate. You start thinking in panels, and time. Even poster artists were starting to break their posters down into panels. The underground comics made me tell stories. It was such a wonderful movement, because it liberated visuals and stories in every direction.”

After the decline of that field, Williams started getting serious about painting. This was a new challenge, partly because he had no peer group.

“The comic-book artists didn’t want to be painters. But all of a sudden the punk rockers come along. And they’re doing this slapdash fuckin’ art, this really crude shitty art but it’s vulgar and they’re showing it in after-hours clubs at night, places that were excuses to sell booze without a license, and I got in with some of these guys, and I thought well—I can do shitty fast stuff, and I can draw! I could work with these guys. And I was embraced.

“My book Zombie Mystery Paintings was just all that crap. Violent, and done with a lot of energy. I found a peer group of young, new, up-and-coming artists. I was getting record album covers and writeups in music magazines. I started this whole lowbrow school out of that. It was a wonderful experience, there, in the late seventies and early eighties.”

In these paintings, and some that followed, he experimented by using multiple styles in each painting. “Like on one side, I’m under the confines of formal anatomy, but over here I can just make it abstract. Sort of like taking LSD. You not only see things extremely realistically but you also see it in abstraction.”

He also experimented with cryptic, verbose text serving as commentary for the art.

“A lot of the things I wrote about my paintings were defense. People are used to looking at art peripherally, superficially. I’m saying no, pal, there’s something here.”

Why didn’t the other Zap artists want to go into painting?

“I don’t know, and I talked to them a lot. Crumb did a little painting, and he was good at it. Gilbert Shelton had been so deeply into comic books, he could not come out. Victor Moscoso did some painting, but kept sliding back into being an abstract expressionist—that milky slop. The one person who really appreciated what I was doing was Rick Griffin.

“He had a propensity for mysticism, and he allowed that to run into Christianity. He loved speculating about the unknown that’s out there and controls you. When I first met him, he was a mystic, but there wasn’t enough in Aleister Crowley to hold him. But the scriptures did. They’re designed to grab you, and he just ate the Bible up.

“He saw me painting, and he picked that up. He’d already been doing album covers. The psychedelic poster thing was dying, so Rick tried to do the painting thing, but he had a problem. He could not do anything if there was not a paycheck at the end of it. If it wasn’t commissioned, forget it. Victor was like that too. They didn’t see the pleasure in a pioneering adventure, and fuck the world.”

I ask Williams if, initially, he was finishing paintings without knowing who would buy them.

“That’s all I did. There was never a check waiting. Never. For decades. Even right now. There ain’t no check waiting for me. I have a gallery, and I’ve been lucky.” He knocks on wood. “But I don’t take commissions. It’s always been happenstance. I went from shitty gallery to shitty gallery, but I’m with one of the top galleries in the world now.”

Indeed, the Shafrazi gallery represents famous names such as Keith Haring and Francis Bacon. Its website retreats into semantic contortions as it explains why riff-raff such as Williams has invaded the pristine gallery space. It references “a formidable faction of new painted realism . . . . It embraced some of the figurative graphics that formal art academia tended to reject: comic books, movie posters, trading cards, surfer art, hot rod illustration, to mention a few. This alternative art movement found its most congealing participant in one of America's most opprobrious and maligned underground artists, the painter, Robert Williams.”

Congealing . . . opprobrious . . . as Tom Wolfe observed in The Painted Word, you can’t have a modern painting without a theory to support it.

When Williams first started achieving some success with his paintings, he naturally wanted to collect them into a book.

“I went to different publishers around, and you just couldn’t have an art book unless you were like Matisse or Picasso. But the underground comics had created a giant network, a sales vine all over the United States and Europe. No one else would distribute them, so they created their own form of distribution. Gilbert Shelton at Rip Off Press said, ‘We’ll do a book on you, but it’s got to be half underground comics, so we sell it through the network.’ So my first book was half underground comics. But this book sold well. It was printed and reprinted. The next book was Zombie Mystery Paintings. That was the first one that was all paintings. I was breaking ground.

“Every idiot, every fuckin’ clown has got a book now. But it started with that fuckin’ book. Do you understand? I’m still ignored or really not cared for by a lot of people. But they wouldn’t have a fuckin’ book if it was not for me.”

Inevitably, Williams’ choice of subject matter and his realistic depiction of it caused some backlash. But he was no stranger to conflict.

“A lot of people just can’t stand me. When I was young—I don’t know how many fights I’ve been in, how many times I’ve been arrested, how many motorcycle and auto accidents, how many times I’ve been expelled from school. So, sensitive art people disliking me is not much of a problem. Individuals who say I’ve violated their emotions is not something I’m worried about.”

One could argue that Williams’ paintings often show empowered women, which could appeal to feminists. But he shakes his head.

“I’ve got the big titties on them, that’s one problem. Really the feminists need someone to attack, and I make a good target. It was really bad in the eighties and early nineties. I had death threats from them. I got a letter from a gal in Minneapolis who was going to kill me. But since then it’s died down.”

Yet he still seems to feel marginalized professionally.

“I am beaten down all the fuckin’ time. I am just continually beaten down. People refusing to tolerate—I can’t show here or there. I can get shows in private galleries, but invading serious real estate like the Museum of Modern Art—you see, art is about the conquest of real estate. If you can hold the real estate, the museums, you’re the genius. Anything looks bitchin’ in a big white room!

“But you have to maintain the fuckin’ real estate. That takes power and planning—so all these people are involved with each other, and have convinced themselves with one premise. And that is, to pass it off as being sophisticated. You have to make it sophisticated because the art world works on one thing. And that is the continual inflow of nouveau-riche young people who have made a lot of money and want to be a part of high culture.

“Nothing looks better in a bank lobby or a hotel lobby or a hospital lobby than abstract expressionism. It’s calming, and it’s not questionable. Abstract expression is fuckin’ perfect. But my paintings are living-room destroyers. I’m on the very thin ice. My art cannot be used as an adjunct to modern architecture.

“I am way in the fuckin’ margins, but still, I have created a school of art, with thousands of young people in it. I’ve created Juxtapoz magazine so that I have a world to function in, and it’s caused hundreds of thousands of young people all across the nation to become artists.”

Did he deliberately set out to irritate people?

“No, no. I want a response, but to stimulate energy in people and raise a curiosity in them, to encourage them to look deeper into what I do. Just irritating people isn’t what I need.

“My paintings are meant to draw you in and hold you long enough to investigate, and instill something that makes you want to see the next painting. So many people don’t like my work, but will look at it to find what they don’t like. If I can get them to do that, they’ll want to see the next one. If I can get them to see two or three paintings, they’ll never forget me. I also want to search out people with my kind of thinking.”

Some of those people have been celebrities, at least in counter-culture circles.

“I met William Burroughs a couple of times. I knew Allen Ginsberg. I was very close friends with Timothy Leary. I was sitting with Leary when he wrote his obituary. I was at his wake. He did an introduction to one of my books. I’d take him hot-rodding.

“Timothy lived like a child, he didn’t lock his front door, he had total idiots come in, and he was doing heroin and all this other fuckin’ stuff. He thought—what else can the feds do to me? He owed the Internal Revenue $400,000 and he was just one minute away from them putting him up for good.”

By being true to his muse and relentlessly productive, Williams now enjoys remarkable success, despite his confrontational attitude—or because of it.

“I am very proud and happy with the art and my lifestyle, because it’s work that I have gotten away with in the face of enormous vicissitudes. Especially in organized society.

“At one time, I had a waiting list of about 350 buyers. I had eight sold-out shows in a row. When the art world collapsed in 1989 and 1990 I still had a sold-out show in New York that blew their minds. New York had 150,000 people in the art world, but only ten people were selling in New York, and I was one of them. Because I never became one of them. I had to generate my own audience.

“I would never have guessed I would be as happy and successful as I am. Being a knucklehead kid, hot-rodder, always in trouble, thrown out of school, put in jail, I didn’t think I had a chance. I’ve been a short-order cook, a truck driver, fork-lift operator, washed dishes. So I have a good idea what work is.”

Does he feel secure at this point?

“No, you never do.”

Although he talks repeatedly about the challenge of making money in the art world, he’s dismissive about people motivated by greed.

“I have members of my family who have had a psychosis toward greed. They could not handle their money, but they’re after money all the time. You could say, ‘Here’s a million dollars, just retire.’ They would take that million dollars and speculate to make more money. And fuck everything up, and bring everyone down with them.

“It’s a sickness, like gambling. They have a belief system that there’s a magic god or goddess out there who’s going to issue them a favor. It’s a psychosis, and it hurts a lot of people.”

Finally, having brought up all the other attributes of his art that I am aware of, I go back to Malicious Resplendence and open it where I have book-marked it for “Patrick Has a Glue Dream.” I mention to Williams that the first time I saw it, I had to laugh.

He seems surprised and not entirely happy about this.

“You see humor?”

Indeed, I do.

“I don’t.”

Now it’s my turn to be surprised. Isn’t there humor in his art?

“I see sarcasm, and abstract thinking.” He pauses, considering the issue. “The Old Testament must go way back, some parts may be 10,000 years old. There aren’t a lot of jokes in the Bible. But in Renaissance literature, you start seeing the first jokes. There’s like irony, and pratfall humor. German humor—the Germans love pratfall humor, people slipping on the ice. The French and the English like smug sarcasm. They like to feel the people in the joke are idiots. When I went to school in New Mexico in the mid-fifties I got to know a lot of American Indians. They had a weird revenge humor. But what is really funny?

“Humor is important, it changes our day. But you show a lot of people expressionism like Picasso did, and people thought it was funny. Distorting things was funny. Consequently, a lot of people in fine arts, and even the higher echelons of fine arts, pin humor on stuff, especially facets of pop art.”

From this perspective, laughter is an elite way to mock or dismiss something serious. But what about a painting such as “Hot Rod Race,” with a 1950s sedan cartwheeling through the air? No humor there?

“Mmm, no.”

With the cops chasing the disintegrating cars?

“That’s the irony of it.”

What about his wonderful poster, which I own, titled “Three Years of Automotive Infamy,” showing Chevy hot-rods from 1955, 1956, and 1957 with a blonde in a bikini sitting on a car engine, retouching her lipstick? That seems—light-hearted, at least.

He remains straight-faced. “I paint what entertains me. But they’re serious to me.”

Okay, one more try. What about one of his most bizarre paintings, of cowboys on horses shooting it out with giant alien amebas driving a 1930s Ford?

“It’s—stupid. It’s not a joke, it’s just crazy. It’s perplexing.”

I can see he isn’t going to budge on this issue.

As an interviewer, one of my cardinal rules is not to piss off the interviewee. Therefore, I have to let it drop.

And so, when all is said and done, I cannot discover why I enjoy Robert Williams paintings in a humorous way, while others don’t—because Williams himself doesn’t see the joke.

“All the stuff I do,” he says, “I think it’s fuckin’ serious. Just as serious as a snake bite.”