To begin, perhaps a few words on MAD.

Banquo’s ghost raises his head at the other end of the table, broken grin unwavering. Blithe nonchalance in the face of total destruction: “What, me worry?”

It always slips my mind to credit MAD as the important cornerstone it was in my own comics reading - perhaps because the magazine, to a degree, existed outside the world of comics, at least in the context of the O’Neil family. It was the only comic book I brought into the house that both my parents also read. I bought MAD consistently every month from very early in my earliest days as a dedicated comic book buyer, very young indeed. Super Specials too. There was always a lot of MAD to buy. They even put out newsstand reprints of the first run of comic-sized MAD, right on the newsstands next to the regular issues. Late '90s, I still have them all. Albeit not in that great a shape owing to the fact that, yes, my parents read MAD too. And that meant the magazine took a beating. The occasional can of Coke spilled upon it. No one ever bought MAD for the purpose of keeping it NM/M.

And then, some time after the turn of the century, I stopped cold. Never bought anything past that point, besides reprints. They kept publishing the magazine. They publish it still.

Whether you can find it in your grocery story is another matter. There’s nothing at all worth stopping to look for on the newsstands, other than the Warhammer magazines that inexplicably you can find in every supermarket up here. MAD always went places no other comic could go because it was shaped differently. My understanding is that it had ceased newsstand distribution around 2019, but I still see it in the store occasionally, so someone must be lying to me. Maybe its just the specials.

When I see an issue on the stands or in the shop, even when I flip through - well, it’s like seeing an old friend. You’re just glad to see them still on their feet, even if you’re not quite sure how they manage to get through the day. Doing a bunch of reprints now? Well, probably for the best, old bean, at least until we get you back on your feet.

I still think the newsstand could make a comeback, incidentally. People still like printed matter, stores still have the dedicated real estate. People don’t like that magazines cost an arm and a leg. First comic book company that manages to put a product on the newsstand that represents a not-garbage value proposition for buyers and sellers alike has the whole lane to themselves.

But I digress. I’m sure I’m wrong about that.

Staying on the newsstands after the turn of the century exacted a price from MAD, and that price was an upgrade - the bargain was struck for color in exchange for paid ads. I could have lived with the color, but the paid ads were a step too far. It seemed a betrayal of principles - MAD bowed to none. Jester’s privilege in the age of mass media. The Man wasn’t going to let anyone but a self-professed gang of idiots make such savage hash of the rest of their non-functioning society. The price of that independence was separation, for better or for worse.

Bill Gaines died in 1992. And despite MAD's gradually closer integration with the DC Comics corporate structure, for a while it seemed the old codicils still stood. Then the magazine was almost canceled in the early '00s. My recollection of the affair was that the assumption had been made that MAD was losing money, when in fact it wasn’t. MAD was nevertheless humbled by the estimation, officially recognized as a coelacanth: a fossil that somehow still managed to pay its own weight. It doesn’t fit into any other paradigm - they did a TV show that was something you watched when SNL was a repeat. Didn’t set the world on fire. MAD sells a few copies in the direct market, but only a few; it’s a magazine constructed for the casual comic reader.

Because of its strange status as an object of cultural ubiquity, I suspect, it’s easy to overlook MAD - at least the post-Kurtzman magazine, separate from its status as a historical relic of EC. Of course, it’s not really quite so ubiquitous anymore. It’s hanging in there, but the age of being a general-purpose digest for school-age children across the nation is largely over.

We shouldn’t take MAD for granted. It let itself be taken for granted, perhaps. Because of its generally ingratiating self-deprecation we didn’t think twice. We’re not supposed to take it seriously. Even though, looking back, the achievement is far more vast than can be readily calculated. One of the largest influences in the history of the medium.

And so we arrive finally to the cornerstone of that edifice - Sergio.

* * *

We all know Sergio. Even if you didn’t grow up with him you still recognize him, the most distinctive style on the stands. Nothing else really looks like Sergio. There are certainly people who we might say take after the master in certain aspects, but no one would ever think to draw like Sergio, anymore than you’d imagine forging Sergio’s handwriting to kite a check. As a cartoonist he is sui generis. Stan Sakai is perhaps the closest current comparison, but the strongest resemblance between Sakai’s venerable Usagi Yojimbo and Sergio’s Groo the Wanderer is mostly formal. Groo is almost pure slapstick from stem to stern. There’s something to laugh at in almost every panel. Not a lot of people do that, outside of the MAD tradition. No one else has ever done that quite like Sergio.

After an early career in Mexico, Sergio Aragonés first appeared in the United States in the pages of the January 1963 issue of MAD. His most recent appearance in that magazine was December 2022. That means, if you’re paying attention, Sergio has been been drawing for MAD almost as long as Spider-Man has existed. Longer than the X-Men have been around. He appeared in those pages exclusively for five years, until one day in 1968 he also popped up at DC, in the pages of the teen humor comics Leave It to Binky #61 and Swing with Scooter #13, both cover dated July. From that moment, he was a frequent presence across DC’s line, specifically anything edited by Joe Orlando. As the '70s wore on, he even appeared regularly in Joe Kubert’s military books.

Sergio was at DC a clean decade, 1968 to 1978, until they changed the contract and he walked. But those were productive years, during which he became the de facto glue holding together the company’s horror and humor offerings. Imagine Plop! existing without Sergio.

No one would mistake the 1970s runs of House of Mystery and House of Secrets for prime era EC, but at the same time those magazines were put together with affection by people who knew EC, and in the case of Orlando had extensive personal experience at the publisher. They could be hit-or-miss. Sometimes you got Alfredo Alcala or Alex Niño or Bernie Wrightson, sometimes you got someone less illustrious. Or perhaps Marvel staffers moonlighting under ludicrous pseudonyms. Regardless, chances were very good, foul or fair, that there would still be a Sergio page somewhere or another. Very ingratiating, those pages.

Horror comics back in the day needed humor to wrap around the package, to leaven the real scares with a chuckle, and mediate the clunkers along the way. They gave a wink to the regular readers and letterhacks. A solid strategy since the days of the Crypt-Keeper, and a not-too-distant cousin of all the various local TV horror movie hosts who proliferated in the days before cable.

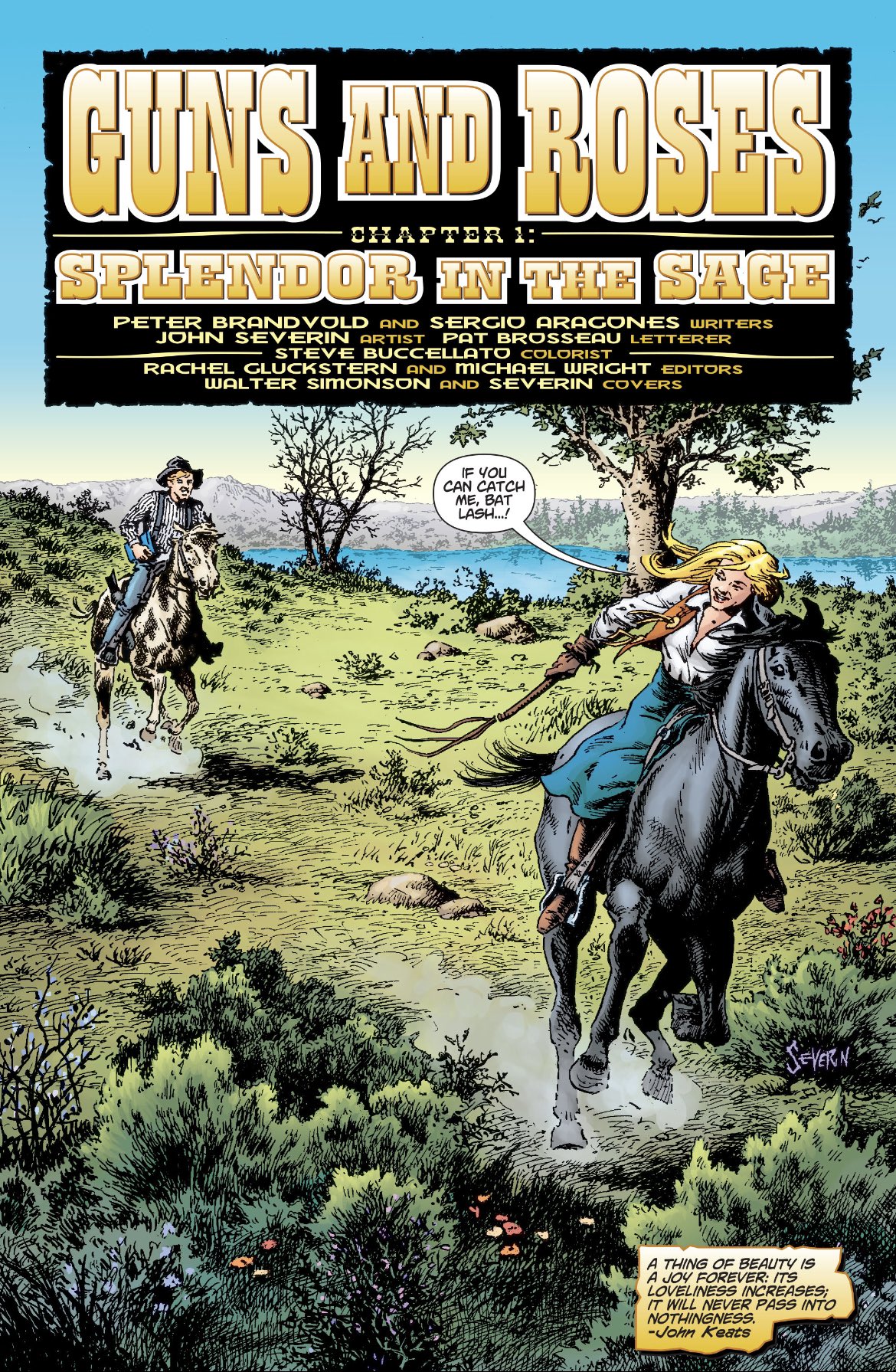

Sergio even did a fair amount of writing. Most notably he co-created Bat Lash, the ladies’ man cowboy who shows up considerably less than Jonah Hex, but still every now and again. Shows up more than any of Marvel’s western guys, at least. He even had another go-round with the character in 2008, with a miniseries cowritten with Peter Brandvold. If you’ve never heard of the series, you’re absolutely going to pop your monocle when I tell you that they got John Severin to draw that thing. John Severin never really lost a step; right up until the day he died he could put out a readable strip. Adding insult to injury, Walt Simonson does the covers.

Now, that was 15 years ago, I say with a deep and weary sigh. Understandable if it maybe slipped all our minds that Sergio Aragonés wrote a western book for John Severin in the 21st century.

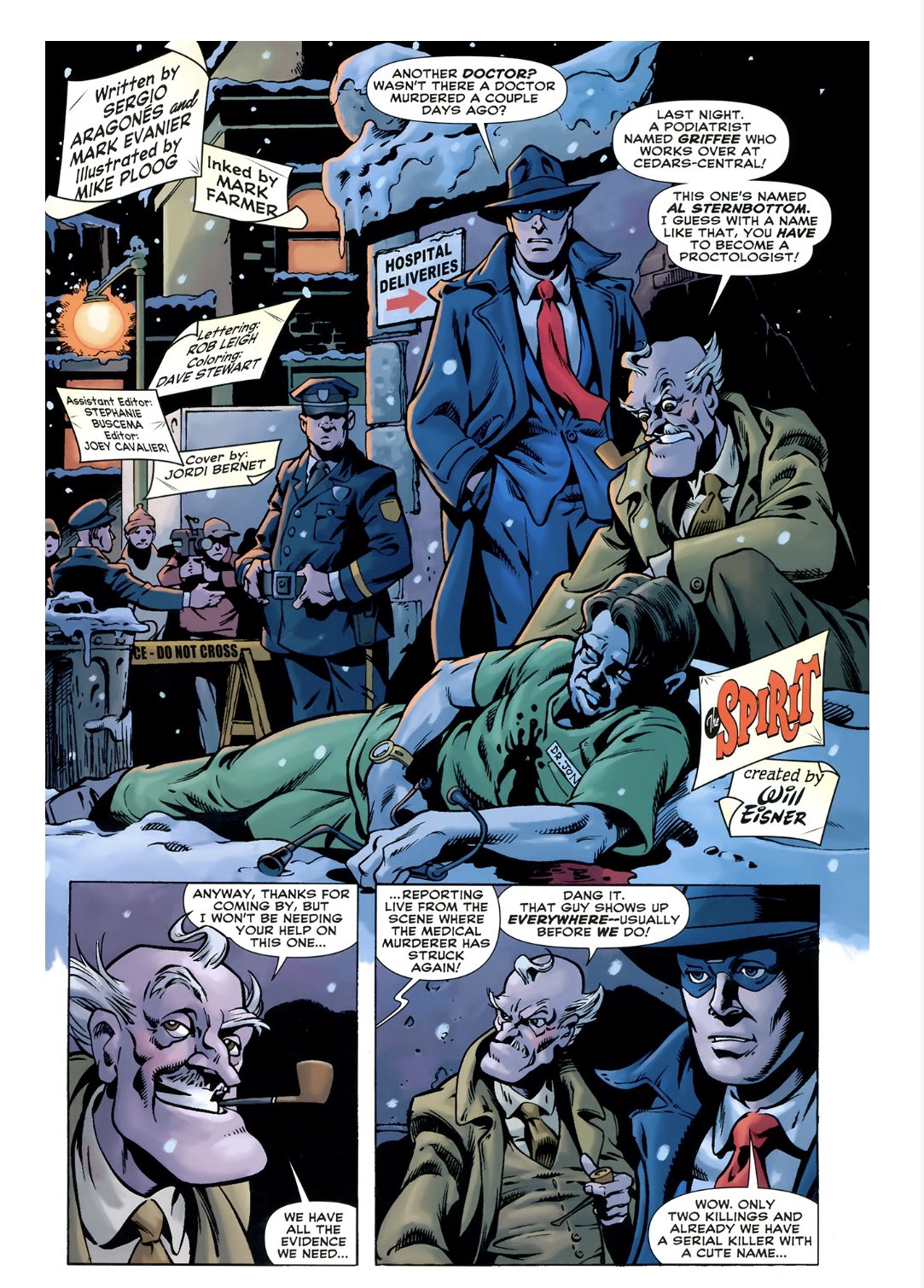

Since we’re in the neighborhood, that’s also around when he did about a year on The Spirit, writing with his customary creative partner, Mark Evanier. Some of that run is drawn by Paul Smith. Aragonés & Evanier succeeded Darwyn Cooke as writers on the book, after Cooke had done a year on the title. Cooke's was the only time, to my recollection, anyone ever had their pulse raised by a Spirit revival - and that’s no flies on the various revivals’ respective creators. The Spirit is not a character DC owns, so there’s limits to what he can do when he shows up for a new run. They usually settle for top-shelf creators coloring pretty closely inside Will Eisner’s lines, which I suppose is part of the fun for said creators. In all fairness, people bring their A-Game to the character, it's clear it's been an honor at times to be asked. And yet a lot of the results read kind of sterile, truth be told.

That year of Spirit is good comics. They’re more interesting as comics, in some ways, than many other recent turns on the character. Maybe because Sergio isn’t at all intimidated by the challenge, in the kind of way that can stiffen the neck of overly respectful creators. As for the art, beside Smith, for their first at bat Aragonés & Evanier were pitching to Mike Ploog. Yep. Mike Ploog drew an issue of The Spirit written by Sergio Aragonés in 2007 - I’d be willing to bet the vast majority of you did not know that.

I did not know that, truth be told, before I refreshed myself with Sergio’s bibliography. There’s a lot of stuff in there! He’s never stopped. There have been precious few months without new work from Sergio on the stands since the presidency of John F. Kennedy. Think about that. Just, you know, roll that fact around in your head a minute. He did a lot of work for Bongo after the turn of the century; even had his own spotlight book, Sergio Aragonés Funnies. There are tons of smaller projects - remember The Mighty Magnor? Fanboy? Louder Than Words? Boogeyman? In June of 1996, Marvel and DC teamed up, more or less, to produce a pair of one-shots: Sergio Aragonés Destroys DC and Sergio Aragonés Massacres Marvel, both filled with superhero-themed gag strips. A couple years later he even did a follow-up for Dark Horse, Sergio Aragonés Stomps Star Wars. Imagine any other creator in the entirety of the medium getting to do something like that.

In any event, it’s only after he leaves DC in 1978, well-ensconced at MAD for almost two decades, that he sets down to work on the character whose adventures over the subsequent 41 years would come to be his opus: Groo the Wanderer.

* * *

Do you know where the first Groo strip appeared? Some of you I’m sure do, it’s a pretty famous comic for completely different reasons: Destroyer Duck #1, Eclipse, 1982. That was Steve Gerber and Jack Kirby at their most vitriolic, a truly unique and truly bizarre concoction born of the two men’s shared enmity towards Marvel Comics. Gerber and Kirby managed to put out five issues with the character. But the debut issue had some guests, like Shary Flenniken - she’s got two pages in the back of Destroyer Duck #1, alongside a four-page vignette starring a new fantasy character by the guy from MAD.

Groo took a little while to evolve. When the strip started it had a bit more of a serious bent, if you can imagine such a thing, with the Conan similarities front & center. But as Sergio continued to develop the character, his features softened, he became less intelligent, and the tone crystallized. He survived the deaths of his first three publishers: Pacific, Eclipse, and Marvel’s Epic line. Groo only ever left Marvel after a solid 10 years, 1985-95, because the company was threatening to capsize. The title stopped at Image for a while, but didn’t stick around for long before ending up at Dark Horse.

Even if they didn’t own the book, there’s no question that Groo filled an important place on Marvel’s slate, in those last salad days of the American newsstand. It was stocked right next to Transformers and G.I. Joe, an all-ages title maybe one step above the Star Comics line, which was aimed at very young children. “All-ages comedy adventure” is a pretty big lane, and underserved from Marvel then and now. Of course, they sold lots of Conan comics too, and didn’t seem to mind also selling funny Conan. I’m additionally certain Marvel didn’t mind having a book with the guy from MAD on the stands at the same time he was doing those fun little cartoons for TV’s Bloopers and Practical Jokes. Those are what your grandma knows Sergio from, incidentally.

That Sergio’s great personal epic can also be summed up as “funny Conan” is perhaps ungenerous, but nevertheless accurate. As creator-owned books go, it's definitely still a story constructed for mass appeal.

How best to describe Groo? Well, he’s a barbarian wandering across a vaguely medieval world, a vast landscape filled with warring armies and dangerous brigands, sinister wizards and noble heroes, crooked priests and corrupt nobility. It’s a well-defined place, with history, economy, industry, magic - a fully-functional setting for Groo to carom across like a bowling ball thrown through the window of a Swarovski kiosk.

As opposed to most barbarian types, Groo doesn’t wield a broadsword or an axe, but two katana. Makes for a distinctive profile. Groo isn’t that bright - in fact, he may very well be the stupidest person in the world. He’s also the most dangerous, and what he loves more than anything else in the world is a good fray. He’s very good at killing large quantities of people in a very short time. If you have an army and that army encounters Groo, you no longer have an army. You now have a field strewn with corpses and a smelly fool looking for cheese dip. He’s also good at sinking ships, vanquishing monsters, and instigating unexpected changes in government - basically, whatever exists in the world can be destroyed by Groo, usually without even trying. That’s what he does. He’s a force of nature.

If all this sounds rather silly, well... yes. That’s kind of the point. Which is not to say that the strip can’t fold in other moods as well, from romance to political intrigue to high fantasy - despite being a completely static character in most respects, Groo can be placed into a lot of different kinds of stories. He doesn’t change, but everyone else around him is forced to react to his presence. He’s got a regular troupe of a dozen or so supporting cast members who cycle in and out according to the needs of the stories - various crooks and con men, mercenaries, scheming witches, barbarian princesses, annoying relatives, even the occasional femme fatale. His closest friends are a self-dealing wise man and a minstrel who always delivers his dialogue in rhyming couplets. Most importantly, he has a dog. A late addition to the strip, Rufferto didn’t appear until issue #29 of the Epic run, but the two have been inseparable ever since. The dog usually gets his own strip on the back cover, incidentally.

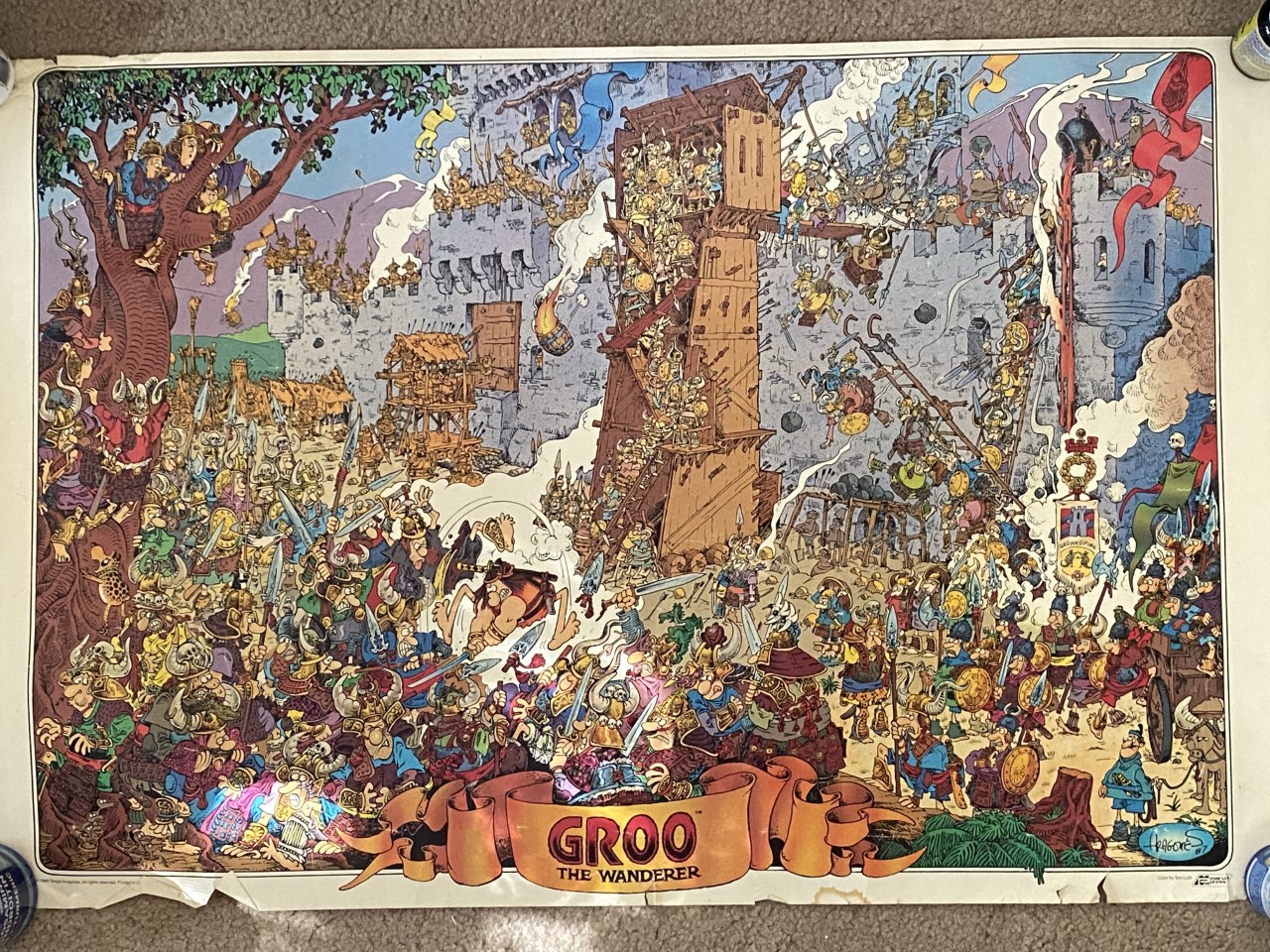

For much of its history, Groo followed a fairly rigid format - done-in-one issues with only a handful of cliffhangers. One issue flowed naturally into the next, such that there was continuity of a sort, with supporting characters and settings changing even as Groo, blessedly, did not. The biggest change the character experienced over the Marvel run was learning to read, promoted as the big event for issue #100. Let’s see Wolverine beat that. Every issue began with a two-page splash accompanied by a poem - there’s lot of funny doggerel in Groo, so if you break out in hives at funny rhymes you may have trouble, caveat emptor. But those two-page spreads are, taken as a whole, perhaps the most impressive illustrations Sergio has ever done. Highly detailed, often focused on architectural or even mechanical details. Lots and lots and lots of little people in every picture, all going about their lives, working, building, eating, fornicating - the whole panoply of human experience, set up like tenpins for Groo to knock down at his leisure.

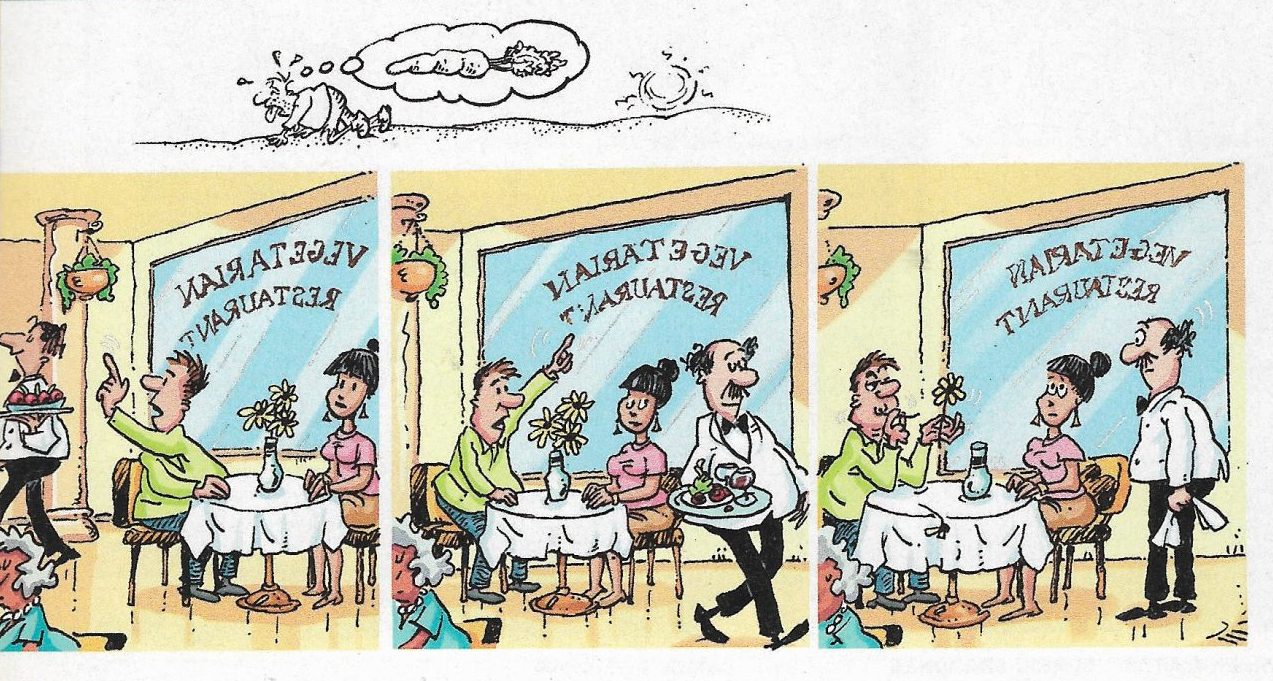

That’s what impresses me the most, truth be told - the profusion of picayune detail in every Groo story. If you’re only familiar with Sergio’s MAD work, you know he can do minimal: figures interacting comedically, often against blank backgrounds, sight gags communicated with absolute economy. Often small enough to fit in the margins of the magazine. He learned to block physical humor from Alejandro Jodorowsky (ostensibly studying mime, no less), and in truth there’s no one better for choreographing physical comedy in comics. He’s in a class by himself there. But when given the chance to stretch his legs, Aragonés can also do maximalism. Besides the pantomime, he went to college for architecture, and you can see that training in everything he draws.

Open an issue of Groo, any issue, and gawk for a moment at the machinery on display. In the first place, there are a lot of machines. How many artists do you know who go out of their way to draw the intricacies of working weight-and-pulley systems? How many artists have you ever seen draw a weight-and-pulley system, period? By choice? Boats have masts and rigging, oxcarts have axles and functional yokes. A battle seen from afar will have literally hundreds of individual soldiers; a dock will have scores of sailors milling about, loading and unloading ships, conducting maintenance. The world of Groo, despite the silliness of its star, is a solid place, one of the most fully delineated environments in comics history.

* * *

This brings us to our putative subject for the day, the recent Dark Horse mini Gods Against Groo, four issues, 2022-23. The structure of the series has changed by now, with ongoing stories and more of an emphasis on continuity. The aforementioned Stan Sakai still does the lettering, but longtime colorist Tom Luth is out, replaced by Carrie Strachan. With that said, it’s remarkable how much Groo has not changed, despite some of the outward trappings. Aragonés & Evanier don’t build every issue around those marvelous double-page spreads like they used to, true. But there’s no shortage of splash pages throughout. The plot can now comfortably stretch beyond the bounds of single issues, and having continuing stories means characters besides Groo get a little more development. There’s a side-story about the Minstrel and his daughter getting thrown into a dungeon by the Queen of Iberza, which doesn’t really have a lot to do with the main plot other than showcasing the Queen’s partial comeuppance. The Minstrel’s daughter was a late addition to the cast, incidentally, and is probably the cutest little girl in all of comics. Cute as a goddamn button!

The plot is actually fairly dense, as these things go: in the first place, Groo is being worshipped as a god on a distant island. This strikes me as the kind of thing that might tend to happen when your actions are classified as an “act of god” for insurance purposes. The act of worshipping Groo as a god causes Groo to apotheosize, so that an avatar of Groo goes to heaven and spends much of the series fighting the other gods. Meanwhile, back in the real world, the aforementioned Queen Isaisa of Iberza wants the gold of Mexahuapan, the island nation that just happens to be home to Groo’s new cult. Frequent supporting cast member the Sage, eternally wise, convinces the Queen of Iberza to send another, larger army across the ocean. This army accidentally lands not in Mexahuapan but Tlaxpan - a land rich not in gold, but jewels. Turns out Mexahuapan and Tlaxpan share the same island, and are fairly evenly matched. The Sage lands at the front of an army of conquistadors, too small to stage an outright invasion of Tlaxpan, but strong enough to augment the forces of Tlaxpan against Mexahuapan in a war for their gold. And the Sage is very confident his plan will work, because Groo died at sea on the way to Mexahuapan.

Except, of course, Groo did not die on the way to Mexahuapan. He’s basking in the warm glow of worshippers and supported by priests who switched over to worshipping Groo when they saw which way the money was going. Just about everyone in the story, at least on the human side of the plot, is motivated by greed and lust for power. Groo is often portrayed as the vehicle of poetic justice to impure hearts. In this context, the most sympathetic character is poor Captain Ahax and the mercenary Taranto, longtime series foils, who don’t want to start any kind of war - they just want to get home with a hold full of precious gems. Without Groo sinking their ship on the way, mind. Groo sinks a lot of ships.

Wait a minute, you stop to ask - Tegan, you just described the Spanish conquest of the New World, sort of. Greedy invaders picking one side of a local political dispute, fanning preexistent rivalries in order to eventually burn the whole place to the ground. Only, you know, foiled by a dumb barbarian who likes to fight. I told you: Groo is a pretty sturdy title. The world of Groo is a solid place. It’s not just that the lever-and-pulley systems work - the historical analogies are well-considered. What Groo shares with MAD is a general distrust of power and wealth. The priests are trying to pick your pocket, the army is trying to steal your gold, even the supposed intelligentsia is easily swayed by get-rich-quick schemes. This unrelenting pageant of venality is tempered only by a tone of unrelenting silliness. Leavens the cynicism. It wouldn’t work quite so well if half the jokes weren’t really bad.

Gods Against Groo is an excellent series. In the parlance of the youths, I “laughed out loud” multiple times every issue. Evanier’s eternally passive-aggressive letters column remains firmly present. Is there anything exceptional about the series? Not really, is the thing. This is another Groo series. The one before it was just as good, and they’ve already solicited the next. They segued into the era of longer storylines without missing a beat. These stories have considerable and surprising meat on their bones. They never flag. For all their familiar comforts, they can even still be weird as hell: they did a Groo vs. Conan crossover in 2014 that qualifies as such. A supremely bizarre miniseries in which Sergio drew Groo and Tom Yeates drew Conan. Half the story is Sergio himself wandering around LA with a head injury.

(Worth pointing out, Sergio’s most famous character is probably his own self-portrait. We don’t think of him in the context of an autobiographical cartoonist, and yet he’s written a lot of stories about himself, in many capacities. He’s no stranger to metatext.)

Therein lies the rub, as a critic, writing about Sergio: there’s no bad Sergio. No subpar Sergio. There’s no struggle, no grind, no reach exceeding grasp. He just is. Fully-formed and functional at every step of his career. His biggest problem (outside of his back, I believe) seems to have been the long process of finding a publisher who would let him keep Groo. When he did find a stable publisher, he sat down and cranked out 10 or 12 years of monthly comics without even blinking. All while continuing to ensure that virtually every issue of MAD has had the little drawings in the margins, of course.

Sergio had to wait a while, following his exit from DC, for the market to allow him ownership of his creations. That the first Groo strip ran in the back of a great primal yawp against Marvel takes on a slightly different air when you realize Sergio would go on to produce the longest-running creator-owned book in Marvel’s history, ultimately only stopping with them because the company was literally falling apart in front of his eyes. Going to Image afterwards was a bold move in context, but fitting. We take it for granted that Sergio owns his own stuff. Him going to Image, at least for a little while, only made sense.

We’re coming up on the 200th Groo comic book, assuming I know how to count (which I probably don’t). That’s really in the upper echelon of creator-owned runs. My sincere recommendation is that the title needs to start showing off its legacy numbering. Remind people you're here. Sergio lets himself be taken for granted, perhaps. Because of his generally ingratiating self-deprecation, we don’t think twice. We’re not supposed to take Sergio Aragonés seriously. Even though, looking back, his achievement is far more vast than can be readily calculated.

* * *

The one time I ever saw the man was at an Image panel at WonderCon, 1994. Perhaps the oddest context imaginable; he didn’t say a lot, but clearly they were happy to have him. Gave some gravitas to the endeavor.

Just that one panel was a big deal for my family, even if Sergio didn’t say much. Because, as I said, my whole family read MAD. And that meant my whole family knew Groo. My dad was often more bemused than anything that I continued to read comics as long and assiduously as I did - but he read Groo too. Groo was different. In 1988 Marvel put out a Groo poster, almost certainly the largest Groo image ever created. A pitched battle in the middle of a castle siege. Groo surrounded by literally hundreds of soldiers, hacking away with glee. Compositionally, Groo is a very small figure in the poster. The castle looms large, assaulted by siege engines and ladder brigades. It’s a funny picture, yes, but also grand - epic on a scale often alluded to but rarely achieved in fantasy art.

The poster itself is actually worth a few dollars, given it was never reprinted. My copy’s all shot to shit, because it actually did hang on the wall of my house growing up. My dad even had it up in his room for a while. Sergio loomed large in my family when I was a kid. My parents came up reading MAD, after all. They were old enough to have known MAD before and after Sergio's advent. I lost both my parents within the last few months. My mother to cancer, my father to Alzheimer’s. It’s been nice to have new Groo on the shelves through that period.

Now, as laudatory as this article has been, it’s also necessary to point out one key mistake Aragonés & Evanier have made. It’s not a new complaint, certainly not to judge by the letters page: there’s no reprint program. I have been given to understand that they’re not fans of the Omnibus as a format. Well, join the club, they’re fun to have but a bitch to sit down and read. There are other options.

The fact is plain: Groo should be a lot more popular and a lot better known than it is. In an era where Bone can be found in school libraries across the country, and Usagi Yojimbo will never go out of print, it’s an unmitigated shame that Groo remains a cult proposition. This isn’t obscure arthouse material, this is broad slapstick and silly rhyming. And massacres, yes, true. But funny massacres. Who doesn’t love a funny massacre? Groo desperately, desperately needs to be able to find a new audience. You can’t do that unless you have a serious plan to sell the backlist. Anything less than that, from such a major figure, is borderline publishing malpractice in 2023.

And Sergio is a major figure, do not doubt. It’s so easy to take him for granted, because he’s always been here. Funny thing, even though Sergio has won every single award for which cartoonists are eligible - he even has an award named after himself, for the love of god! - it still somehow feels as if he is wildly underrated. How is that even possible? How does it feel like we still haven’t come close to appreciating his talent?

Sergio has no peers, not anymore. He’s nothing less than our greatest living cartoonist. In 2023, there’s no one else even in the same neighborhood. We, all of us, had damn well better start acting like it.