I came across the work of Panayiotis Terzis back in 2007 at SPX. His comics amazed me then and they still do. His Mega Press publications and his personal riso experiments make him a perfect person to bring into my series on the "pioneering" risograph printers.

Check out the previous Risograph Workbooks: Risograph Workbook 1: Mickey Z; Risograph Workbook 2: Jesjit Gill/Colour Code Printing; Risograph Workbook 3: Ryan Cecil Smith; Risograph Workbook 4: Ryan Sands/Youth In Decline; Risograph Workbook 5: John Pham.

I'll turn the mic over to Pan now:

================================================

Santoro: Tell me about your current copier setup. What machine(s) are you using?

Terzis: I've been running an EZ 390U with five colors for about four years or so, but over the past two years I've been printing on a pair of ME 9450U models, which are the newest Riso duplicators on the market.

Tell me about printing other people's work in your anthologies. I imagine that many of the artists you work with appreciate the attention to detail, and may have never even printed their work on their own before. Can you talk about that back-and-forth?

Well, I never planned on being a publisher of anyone's work but my own, but printing and publishing artist's books and zines often entailed collaborating with other artist friends, publishing projects with collectives where we'd be handling the work of dozens of other artists, and trading with other artists in the scene at book fairs and events. So my earlier small scale publishing activity always had a social aspect either embedded in the process and structure of the book or the way the individual copies would circulate afterwards.

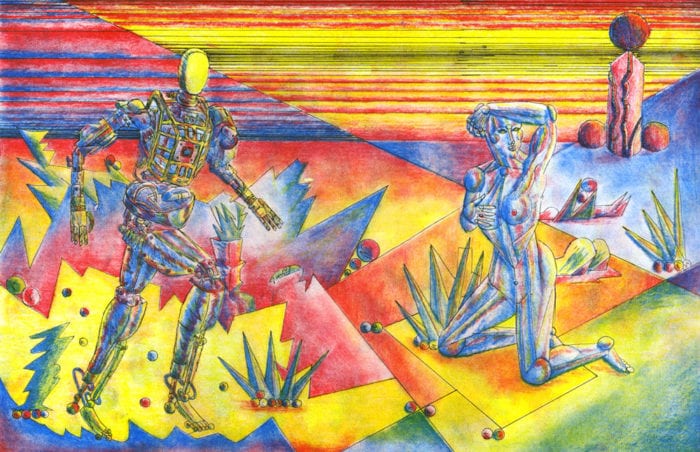

It wasn't until 2013 that I was possessed with the idea of making a publication designed to capture the dark energy that I felt was encircling the globe and pressurizing the human race - I made the decision to take a more intentional approach. I couldn't think of any artists who were trying to grapple with the renewed stirrings of nationalism and neo-fascism in the west, the beginnings of a sort of techno feudalism, increased authoritarianism around the globe paralleled by the expansion of personal electronics equipped with surveillance capabilities into every second of our waking lives, against a backdrop of a coming collapse of the biosphere. This nasty, aggressive dystopian sci-fi publication was originally going to be a solo project, but I started thinking about how interesting it would be to invite artists I knew from various art contexts—painters, underground comics people, photographers, etc.—and offer them a chance to respond to this dark energy I was detecting.

This book became Trapper Keeper, the name re-appropriated to evoke a near-future bounty hunter empowered by the state to track down and apprehend individuals wanted for offenses ranging from unpaid parking tickets to overdue student loans, jaywalking, subversion etc. — a cross between Boba Fett and Judge Dredd rendered by JG Ballard. What kind of world would the Trapper Keeper live in? I am now preparing Issue 5 to be released at Safari Art and Comics Festival in London this August.

There are a range of approaches artists I work with take when they send me their files. If they have knowledge of color separation or any experience with traditional printmaking, many are happy to send files that are ready to go, with the knowledge that the end result will look a little different. I work closely with those who aren't familiar with print media, but if someone doesn't know how or has no desire to work with an image made up of spot colors, I'll have them send me full-color flattened files and I'll just split the channels and print them using a faux-CMYK printing technique using the colors I have access to that most closely resemble process colors. The color balance always shifts, but certain images translate beautifully.

In general I've had very few instances of artists being overly precious or concerned about their work changing too much. If someone is working with me and they know my work, they usually trust me to treat their work with care and respect.

Publishing other artists' work has been extremely gratifying. I benefited early on from other people going out of their way to publish, promote, show, and sell my work so I feel I owe a debt of gratitude to the universe and it feels good to give other artists the same opportunity. I always try to compensate artists financially when I can. Artists who I commission to publish solo books usually get a fee and a proportion of the edition, and I pay the cover artist for curated group projects like Trapper Keeper since I do eventually make a little money on these editions.

It is quite satisfying to assemble a dozen or so artists who each have a powerful, unique perspective, ask them to respond to a common theme, and then arrange their work in the form of a printed publication. It's like painting with the work of my peers. Each issue has a secret formula that I have to discover. Once the proper order has been determined everything locks into place, and the thing is weaponized and ready to be printed and dispersed into the world.

What is your risograph origin story? I assume you were interested in printmaking before you discovered risograph printing. You've been making interesting color work for as long as I've known you. How has the risograph changed your process?

When I was in undergrad I had discovered and cycled through all of the traditional forms of printmaking - etching, lithography, screenprinting etc. I was making paintings, drawings, installations and comics, and printmaking was where everything came together. David Sandlin's class was monumental for me in terms of challenging myself technically and aesthetically. His work was so ambitious and beautiful that I think it made everyone in his class work their asses off to even be worthy of being there. It was inspiring to be around an artist who made comics but who also had carved out a place for himself in the art world without any contradiction between the two. He was also a living connection to various legendary creative worlds I'd been reading about: the East Village scene in the 1980s, all the people who had been involved in Spiegelman's RAW. Around this time I had also discovered Fort Thunder, Space 1026, and Paper Rad, and all of the other little versions of those phenomena that were unfolding in small cities all over the country and in Europe too. Using print media, making cheap multiples, making posters for events — all of this felt very fresh and democratic, and part of a creative outlook that demolished the barriers between contemporary art, music, performance art, zines, books, comics, painting, and commercial art.

After school I worked as a print tech, printer, and freelance illustrator, but I continued to use screenprinting and other printmaking media to print and publish my own editions of books and prints. This was crucial because it allowed my work to spread faster in the form of affordable multiples than if I was working primarily on unique pieces and waiting around for a studio visit. My zines and books ended up in unusual places, thanks to distributors and early supporters like Dan Nadel and Printed Matter who brought my work to art fairs and got my books into museum collections and galleries, to be discovered by all kinds of people who would then track me down with ideas for various projects and opportunities.

Around 2009 my friend Alex Damianos started bugging me about this "Risograph" that he had recently purchased; he kept suggesting that I use it to publish something. He described the machine as an automated screenprinter, and I pictured some kind of box with a crank, water and paint spilling out the sides. When I finally saw the thing in person I was a bit disappointed; it just looked like a bloated copy machine. But when I opened it up and handled the drum I was intrigued and decided to give it a chance.

UK based comics artist Leon Sadler and I had been kicking around ideas for a collaboration via email for half a year at that point, having originally started a correspondence after Switzerland based publisher Nieves put out a solo zine by each of us in the same month. I decided to use my friend's Riso to print and publish this book. I remember it was down to the wire because I had to have it ready for a book fair that was happening in just a few days. He left me with his Riso and in twelve hours I was able to print 55 color layers for a 32-page book in an edition of 100 from start to finish. This was a complete game changer for me in terms of production, speed and quality - if I had screenprinted this book it would have taken weeks if not months. The implications left me giddy. I could make bigger editions faster and sell them at a much lower price point. I was obsessed.

The process of printing was very dynamic. On the one had I was working with this bulky, awkward machine that looked like it belonged in an accounting firm in the mid-'80s. But the process of opening up the machine and changing the enormous drum cylinders to print different colors felt very futuristic, as if I was arming a nuclear warhead on a small spaceship. Between dealing with the guts of this technology and the manipulation of the speed and position of the print, I could indulge in being a technician.

My project with Leon Sadler was the perfect book to publish as my first Riso project, as we had been sending work back and forth in a combination of digital and physical form without actually having met each other yet. The content tapped into a feeling of the future as well as the ancient past, and the Riso process to me had everything to do with the blending of art and the technical, digital and analog, past and future. These ideas are at the core of what I find interesting about printmaking in general. Working with any print media in 2017 is a perfect excuse to think about all of these things, but especially the ongoing tension between man and machine.

For a few years after that whenever I had a larger edition of books I was planning to publish I would seek out friends with Riso duplicators to print them on in exchange for helping them out with a project that required some other skill or resource I had access to. In 2013 I decided to purchase my own used Riso to publish Trapper Keeper and formalize my publishing activity under the handle Mega Press. It was a small investment to get set up, but I quickly made back the money I had spent on the machine and drums through freelance printing gigs that materialized almost immediately.

I've noticed risograph printers have "meet-ups," little fairs and conventions. I imagine it is like any other subculture, however this one interests me because of the direct connection to book making. It reminds me of zine culture and comics fandom in a way. Can you speak to how risograph printers are different than other printers beyond obvious differences in materials?

I'm not sure that there are any Riso-specific fairs that I can think of apart from Magical Riso, which is a conference held at the Jan Van Eyck Academy in the Netherlands, but at this point any of the major fairs - NY Art Book Fair, CAB, etc. - end up becoming mini Riso conventions because of the Riso printers and publishers. It's a very small world and everyone knows or has heard of each other.

The machines themselves are basically high speed stencil printers. When you're working with a Riso duplicator you have to design an image with specific spot colors in mind for each color drum. So the process combines the automation and speed of an offset printer or xerox machine with the quality of a fine art print edition.

The kinds of people who become Riso printers usually have a background either in design or printmaking, but everyone becomes a bit of a print tech when working with these machines since they're so expensive to fix - as cheap as they are to run, you need to learn some basic maintenance techniques to keep them going without spending a fortune. So when Riso people get together the conversation inevitably crosses into heated debates over which blue makes the best faux-cyan, whether the newest metallic ink is overpriced or actually worth it, which Riso secondary market dealers are crooks, and down the rabbit hole into the subject of master skew, what common hardware store items can be substituted for transfer belts, how to fix the timing on an MZ duplicator, or whether it's worth it to refill used ink tubes and replace the chip so that the machine is tricked into using a different ink.

The main thing to keep in mind is that this medium is neutral - you can make any kind of work with it if you know how to use it! And there are many ways to use a Riso printer. It's potentially a technical medium even though you can use it in a really simple way. So in nature it's probably a bit more like used car enthusiasts getting together than comic or zine fandom. Many Riso printers also do freelance printing for clients, so there's a little bit of a working class contractor mentality that slips in as well.

Personally, I am fascinated with how risograph printing has changed making color comics. Before risograph was around the choices were expensive offset or expensive print on demand. And often dealing with those printers was difficult. The riso printers I have engaged are not faceless sales reps on the phone who have no experience making comics. So riso printers and their enthusiasm for the materials has reinvigorated the small press scene - which has drifted into "book publishing" (like giant offset press books) - and I was hoping you could speak to that?

I agree that this has breathed new life into the underground publishing scene - but let's not forget that this is just the latest wave of a rising tide of revived DIY publishing activity that has exploded over the past 15 years in spite of all of the digital hype and "print is dead" bullshit that came along with "web 2.0" and the commercialization of the internet. Those big beautiful books you're referring to make me think of the Kramers series, and many of the things PictureBox was publishing - a lot of that work was originally printed by the artists themselves, many of whom came out of printmaking and used those skills to empower themselves and spread their zines - and show posters for their noise shows or screenings or performances - all over their local scene. Your own Sirk zines are a perfect example - I have a copy of your Storeyville book where you explain how you made color zines back in the 1990's by manipulating one tone at a time, running it through the xerox machine one page at a time, so you could deploy a process similar to traditional printmaking, building up each layer by hand. A lot of this type of work was then collected and published in really nice editions, and other small presses followed the same formula. The Riso allows artists to take the means of production into their own hands again without needing an entire print shop with all the space, plumbing, ventilation and materials that that would require.

In my experience color can be a challenge for some cartoonists. The best way to begin to understand color and develop your own personal color sense is to limit your palette. You begin by comparing two hues at a time, and how they affect each other. Once you understand the relationship between individual colors you can gradually increase the number of colors you're working with, experimenting and making small adjustments until you develop a personal feel for the palette that resonates with you. The Riso is a perfect tool for the study of color because you are designing in layers of specific overlapping colors. Additionally, one can make a design and quickly test it out with various color combinations. Since layers have to be prepared in grayscale, it also helps one understand value and it's relationship to hue.

Riso printers are a mixed breed - many are strictly publishers, but with a fine art printmaking background. Many - like myself - are artists whose independent publishing practice of printing their own work expanded into larger operations, publishing the work of other artists as well and incorporating into an intentional publishing operation. I think most Riso printers have some kind of background in art or design, and to a certain extent they can communicate with artists and understand their perspective and goals whether they are publishing these artists or doing contract work for them, printing their zine or poster. I think it's a different perspective from the offset press operator or the copy shop employee because their identity and ego is mixed up in their business in a different way than old school print contractors.

Can you talk about the "crossover appeal" of risograph? Meaning that the quality of the books you make for example seem to appeal to the "high and low" of various outlets, stores and fairs - whereas in the past it was difficult to get a store like Printed Matter interested in xeroxed minicomics - nicely produced risograph comics seem to gain more traction - it's a different landscape than even ten years ago...

I'm someone who has always been interdisciplinary; I studied painting, comics, illustration and printmaking in school, and I've worked across different commercial art fields - illustration, textile design, design - and my work has circulated in gallery, print and underground comics contexts. These divisions are arbitrary and more reflective of social cliques that make up the people who populate these scenes than a real difference in content, style or intention. I think it's unfortunate but what I love about making and facilitating the making of printed ephemera using Risograph printing is that it really can bypass these barriers. It's unclear to me whether the floodgates are being smashed and all these different ways of making work, different formats, different perspectives, are pooling together into a chaotic whirlpool or if the barriers are being reinforced. It's a kind of Internet paradox in some ways - all of this openness and exposure to difference is causing a reactionary backlash politically, where people are seeking ever more narrow and specific identities to differentiate themselves.

I can be equally inspired by a Max Beckman painting or a Takeshi Murata video as I am by an ancient Mesopotamian fertility statue, Aztec totem or an unintentionally brilliant in-flight Skymall catalog. The work I curate reflects that, and I'm always including installation artists, painters and other artists who know nothing of the underground comics/comix/publishing scene with people like Lala Albert, or Lane Milburn. Every issue of Trapper Keeper is carefully curated and balanced. If I've confirmed a lot of artists who are heavy on drawing chops maybe I'll add a pinch of Ben Mendelewicz for a demented stock photo/Nickelodeon Gack/West Palm Beach/Haunted Photoshop feeling to cure it. Or someone like Brenna Murphy, who works with digitally rendered forms that are then turned into 3D installations that are often folded into her band MSHR's performances. The crossover appeal is a built in feature of any project I work on, especially if it involves curating other artists, because the different social groups and followings that each of these individuals has makes these contrasts seem more extreme.

Riso printing, even in a single color, will always look nicer than xerox. Also, it's better for the environment and your lungs! When you're printing with a xerox machine, you're melting plastic dust and sealing it onto a sheet of paper. Riso ink is soy based - you're literally printing with bean juice!

One thing I'd like to mention as a final note, related to the interdisciplinary aspect of Riso printing. The medium is neutral; the only thing every Riso print has in common is the limitations of size, color and the microscopic perforations in the Risograph drums that all Riso ink has to pass through. A couple of years ago, I was recruited by Nathan Fox to help found a printing space dedicated to Risograph printing - RisoLAB, at SVA in NYC. I've been teaching classes there and helping to run the space, and it's incredible how we are being flooded with students and graduates from every creative field who want to use the Riso to actualize their ideas in print form. Illustrators, Cartoonists, and confused painters are to be expected, but curators, installation artists, poets, writers, photographers? The range of work that has been produced is amazing, and is an important reminder that Risograph printing is accidentally relevant because the "commons" that we have been left with as our public spaces have been eroded and commercialized and our local communities have been destroyed. The internet/social media is increasingly unsatisfying, and even unpleasant.

People want to show up. They want to look at your thing in person, hold it in their hands. They want to talk to others in person about it and look at it at their own pace, without the publisher or distributor knowing how long they spent lingering on a page or whether they got to the end of the book in the same time as 76.3% of other consumers. All of this activity is still happening in the context of capitalist systems of production, supply and demand and distribution, but I think that people who work with this kind of cultural ephemera must know on some level that the real art is what happens in between the object and the viewer, and the consumer of that piece of art and the person they describe it to. It's inherently a social act, and this can manifest through all stages of the process. People-power is what drives this activity, and just like a blade of grass can slowly destroy a piece of concrete given enough time to push to the surface, I think DIY culture might be the key to breaking out of the mechanistic, algorithm driven nightmare that our tech overlords are driving us towards.

I've spoken to a lot of Riso printers over the past year who feel that we might be hitting peak Riso. Fads come and go, especially in a subcultural context. But what if this kind of Riso printing doesn't go away - what if it keeps exploding until there's a local Riso printing space in every community, where some teens are printing their anarcho-punk militant gender queer zine on an MZ 1090 while their grandmother prints a book of her family recipes on a GR 2450U in the next row of duplicators? I think that we need to think about the possibilities and implications of this process, and how it can have broader possibilities that extend far beyond catering to insular subcultures of comix people or photographers or design bros getting in some "personal projects" on the weekends. People are hungry, they're desperate, but they're excited and hopeful. In my capacity running the RisoLAB, I see it every day. Let's hope that we don't screw it up.

============================================

Check out more work by Panayiotis Terzis at his website, see what Mega Press is all about, and stock up on issues of Trapper Keeper and other work at the Mega Press store. Pan will be releasing Trapper Keeper #5 (featuring a cover by Robert Beatty) and some other new zines for the Safari Festival in London in August.