Frank Santoro's long-gestating project Pittsburgh will soon see publication by New York Review Comics. In anticipation of the book's release, we asked Ohio State's Caitlin McGurk to speak with him about the book. All images are from Pittsburgh, and Frank's author photo was taken by McGurk.

Frank Santoro's long-gestating project Pittsburgh will soon see publication by New York Review Comics. In anticipation of the book's release, we asked Ohio State's Caitlin McGurk to speak with him about the book. All images are from Pittsburgh, and Frank's author photo was taken by McGurk.

Caitlin McGurk: So, you know how much I love this book, right? I think I’ve read it half a dozen times. Do you feel like you’ve been writing this book your whole life, and if so, what made it come out of you now?

Frank Santoro: Oh! Thanks for saying that. I do think, sure, I’ve been writing this book my whole life. I would hear a line, like in my head, and I know some of the stories so well and have heard family members tell the stories so often that, you know, I can hear it. I hear their voice. And then when I put it all together, I wasn’t sure about how to make a cohesive narrative because it only makes sense to the person who lives that life. So I don’t know why it came out now, I think it’s because I wanted to do something while my parents are still alive so that they could maybe read it, or I would bring them together again somehow through the process, which didn’t work of course [laughing]. But you know, that’s something else. But I never thought I would do it, I never considered autobiography as a choice in making any work. Even self-portraits were strange for me to do. I could try to unpack that. Sammy Harkham did a strip about meeting my dad and he put it in Crickets 3. He met my dad on the street outside the venue during the Kramers 7 tour in 2008, and he just did this one page strip about talking with my dad and my dad telling him his whole war story... to a stranger. And Sammy remembered it, and wrote it all down and it was correct. I remember showing it to my dad and he was really struck by it, and was sort of like, “This isn’t going to appear in a real comic book or anything, right? Are people going to read this?” and I downplayed it. But it messed me up. Like in a good way. Because in my book, I talk about how I didn’t know many of the stories about my mom and dad until I was 30 years old, and yet here’s my dad telling his most horrible personal stories to a stranger, and Sammy making art about that kind of unlocked something in me. The first two pages of Pittsburgh are where I kind of… wrote them out of a need to respond to that. I started hearing the story in my head, and it was a good story. My mom’s in high school, my dad’s in Vietnam, and they were already together, and it just happened. And then weirdly, that was the moment when you could start scanning art made out of pencil and crayon and it looked good on the computer… maybe 2009 or something. Just the way blogs worked or the way things were uploaded, I just remember if you printed the same images in a zine it would have looked kind of pedestrian. I just remember the first two pages I had made for one of my columns on some blog and I just embedded it in a column I had written about something else. And a lot of people responded to that, like Dan Nadel, my publisher at the time at PictureBox. So that’s how it actually came out now, the actual project. But it’s a weird thing, to have this store of information for myself and my family and everything, and it’s actually what I always wanted to write or draw or spend time with, instead of like inventing narrative or working within genre restrictions.

Yeah, I mean, it makes sense to me that seeing Sammy do that would set off some alarm inside of you to reclaim ownership of the story. Not that he did anything wrong, but that, holy shit, this is your family story and there’s so much you haven’t even found out about yet or processed that you could get out there. So I completely understand that. I think it’s really interesting that you had never done autobio before this. How do you feel about it? How was that process? Do you think this is going to be something that you continue to work on in the future?

Yeah I wondered about that because there’s so much on the cutting room floor that I left out, and I had to sort of make my mom and her side of the family the villains in the story, and I feel like their whole story demands its own book so I resisted putting stuff in. Every time I introduced new family or characters it would just overwhelm. So I was just like, I really have to keep it to the nuclear family, just mom, dad and their parents and the periphery characters. Every family you hear stories about “uncle so-and-so” but you might not see them, you might not ever meet your friend’s uncle who you always hear them talking about, but you can tell these family stories in a short hand… but I might make another book that is my mom’s side of the story, or my mom’s families side of the story, I don’t know. This book was so hard, but not hard. Like I’ve read a lot of interview with people who do memoir and we all say the same thing, “I had this amazing story” or “my family had this amazing story that I just had to tell, I had to tell the story and I had to get it out and I had to do it” and that’s where I start thinking that it is a genre, like you have these particular archetypes that have to be addressed whether you have them in the story or not. But I don’t know how I feel. Everyone has different opinions about autobiography, especially autobiographical comics. Many graphic novels are pulled from the author’s experience for sure. They’re often Roman à clefs. They are so common in fiction that I think you could say Love and Rockets is a Roman à clefs in a way. You know they’re weaving fiction out of it, they’re creating characters, but you can see the authors and their families so clearly in the narrative. So the choice is just doing purely autobiographic stuff or not. In this book, I work better in limitations and so the limitations I set up were just to keep it within my parents and their parents.

Did you use a lot of photos? There are so many beautiful drawings of empty rooms and stuff like that, and I just kept wondering, are you doing this from memory or are you using photo reference?

No, memory. There would be like a blurry photo of like half of a living room, or something, you know… people sitting on a couch, and you see part of the living room, but I don’t really work from photos. Of course there were times when I had to use photos, but no. What I wanted reference for…those photos don’t really exist. The feeling that I got from sitting and trying to remember the rooms was really why I made the book. Like I was really only interested in the feeling that I got while I made the thing, and then piecing the pieces together and layering the narrative over top of it was really like a concession and a compromise, because if it was just a painting I could just explore all of these things… all of these details. But as soon as you start making specific details of the room then they take significance in the narrative and you have to be careful that you don’t draw the hell out of a lamp, because then the lamp becomes the focus of the narrative in that scene. So yeah, memory. A lot of drawing from memory and some photos for sure.

I think what you’re saying is what makes me love this book so much. I’m very interested in memory and comics. And the way you have done this... reading this book feels like watching someone remember something… or being part of their process of remembering. Memory is so hazy and so layered, which is reflected in the way you’ve drawn this book. There are a lot of points I want to ask you about within this specific question, but one of the things I thought was so effective is your use of... I wouldn’t even call it sound effects... but the way you describe sound and physical sensation to add to this broader experience of being within this narrative. So there are times where you write things like “grocery store shopping cart rattle of wheels” and, for the physical sensations, “hot pavement on feet” or “morning heat of sun on bus windows” and that just makes it so rich to me. It’s so specific, and it seems so key to how you’re capturing this stuff. It’s fascinating to me and I think it’s way more successful than straight up ontomatopoeia, because when people are using that I tend to literally hear the word “sizzle” in my brain rather than actually hearing something frying. But your use instead of “grocery store shopping cart rattle of wheels” ...I can hear that so much better.

Yeah, thanks! It’s kind of corny but yeah I’m interested in poetry, and I think that we hear phrases like that in those moments and you throw them out there, and I think they rhyme with the images. And when I make drawings in the field, a landscape or something, you can just describe the bird that went by, like in one point in the book I write “cardinals singing,” and a cardinal makes a specific sound and a lot of people in this part of the country know that sound. So there’s that, and this just comes from my experience. That was a natural process for me from notebooks and drawing on site, and I always thought those notations were just as relevant as the drawing of the landscape itself. Or like if you’re drawing a portrait sometimes there’s music playing in the background, and the music that’s playing can add something to the portrait, but how do you write that on the painting. And what’s great about comics is that you can write that as a sound effect or something and you can just quote song lyrics, or in this book I just say the song, and people can look up the song themselves if they so choose, and for me it’s also like this translation thing… like I don’t like sound effects because I know that my work is going to be translated into another language and so when you embed the sound effect into the thing, you always have to remake the art for the new word, and that new word is going to have a different size, different font, different everything. A lot of that came out when PictureBox translated Yuichi Yokoyama’s books and he has a lot of sound effects embedded in the art so clearly and he would make notes that describe what that sound effect meant so he would say “Brrrang Brrrrang Brrrang” and so on the bottom of that page or panel would be written “crane moving” or “steam roller”, and that was his description of it. So his beatnik poetry of sound effects, in English, from the Japanese version, were what I thought were really interesting and poetical little bits. And I know that those bits informed me when I was making work ten years ago and as I started making Cold Heat and Pompeii and I would start to incorporate that and with this book I could be much more specific with how I wanted to rhyme the images with “hot pavement on feet” and those things are not as calculated as I’m maybe I’m making them sound, but they’re just in the process and I hear them just as much as I see things or I hear bits of dialogue and just write them down and if they make it into the manuscript that’s good.

They’re in the memory, and so I feel like that’s what makes it so much more complex and realistic. When you are remembering something you’re remembering these hazy images but also sensations – it’s not just visual. It makes it even more real I think.

I would say to myself when I would start to draw a room, I would say to myself that I wanted to stay in the scene. A lot of times I would want to push the narrative too fast to “and then what happens and then what happens” and then I would just draw another page of that room, and another page of that room, and make a different angle… the light would change, a figure would appear, a family member or something… and I would just stay in that memory. And as I stayed in that memory, more memories came to the surface. And that’s what I mean about the feeling that I got while making it. It really felt like some kind of sport where you’re paying close attention, like tightrope walking, I was so focused on what I was doing cause I was really enjoying what I was doing. I can’t think of anything that I would wanna draw more than some of the rooms I was drawing.

It sounds really meditative to me, and I was wondering about the state of mind that you had to get yourself in every time that you sat down to work on this.

Yeah it was hard. I’m a cryer, I cry easy, I pace around the house a lot. And you know I’m going through old family photo albums and you just feel the family member’s presence, whether they’re still with us or departed, and I feel like they’re there. Even if I said things about them in the narrative that weren’t kind I felt like my mom’s mom has the best line in the book, even though she’s really cast as the villain for wanting to send my mom to California to keep my mom and my dad apart. But I just gave her the best line, which is when I ask her directly if she was really going to send my mom to California when my dad was in Vietnam and she says “No of course not I was never going to do that. I said “it’s a good story” and she says “that’s all it is, it’s a story.” And you know I told my mom that bit and she says “Oh, she’s full of beans” and I love all of that. I think my family, if they were still here to read that, might judge it. I get lost in all of that. Thinking about all of that. That’s what’s interesting about this book. It’s about how I made it. Like with Pompeii, it’s more about how to depict the thing that everyone knows in the story already, the eruption of a volcano, it was more like about how I was going to tell that story and where to fit the volcano in. But with this, nobody knows the story. Even telling people at shows in France, they would ask “what’s the book about” and I’d say “it’s about my parents,” Whereas with Pompeii, no one asked me that. And so it’s an interesting thing to try to whittle down your life story into a back cover text to just explain it simply.

It seemed like parts of the book were based on interviews you had done in the past with your family members.

Yeah, I would interview family. Did interview them. That was my trip back in the 90s after I did Storeyville. I was visiting Pittsburgh and I was going to make a book based on my neighborhood but called it something different than its actual name (Swissvale), I was going to call it Fairvale, and I was working with Bill Boichel from Copacetic Comics and we had all these characters and I was interviewing my family about Pittsburgh history, like “What was it like when the train station was across the street?” and “tell me about that” and in the process I’d get them to tell their story. I’d say “say your name, say how old you are, where you’re from…” and especially older people, they talk like they’re on the evening news or something. They’re very formal. And I enjoyed that. So I said it was about Pittsburgh history but it was really to get them to tell me these stories. So I’ve had a lot of that material for a long time.

That’s amazing, that’s so great that you were able to do that while everyone was still alive, and could hang on to it for this long.

I would just steal their stories, like they would have a story about working in a steel mill and I would apply that to a character we had, you know. A lot of people do that for fiction of course. So I was making a genre thing, but we wanted to make archetypal characters. That project was happening during a hard time in the 90s, hard to get anything published, so it didn’t really go anywhere. It was kind of my fault, I had way too much to do. I wasn’t capable. Like model sheets… that was when I tried to tighten up my drawing style and get more professional, and then realized that was probably not the way I should draw. It’s different now to think about that from 20 something years ago to now, there’s just different ideas about finished art and what finished art is.

To that point, talking about the memory stuff, since a lot of the drawings in the book look quite sketchy and organic, is that actually true to how they were made? Or are there tons of versions of each page as you were working through it?

Nah, everything in there is the first time I drew it. I never thumbnailed it or wrote anything out, you know, I subscribe to the Chris Ware school of comics making which is that it’s a visual medium, and you begin by drawing. And you write while you’re drawing. The words and images come at the same time as you’re moving things around on the page. And that was the other thing about making scenes. So I would just make one scene and say “okay this scene is going to take place outside of this building” or on this street, and it will be these characters, and I’m actually just making a drawing of a family member or friend, and I’d cut them out of a piece of paper and stick it onto a drawing and looking to see if that works. And a lot of the time those are place holders and then sometimes I would remake that drawing and there would be another version of that drawing on the cutting room floor but they would look like the first version. Sometimes I’d then put tracing paper over something I drew months ago and fixing the face, making it a little more specific.

And all of that shows up in there cause you’re working with tracing paper, so we get to see all of these layers of your process.

Yeah, so the feeling is there, the feeling of really trying to remember this, So it’s not like I’m gonna make a sketchy drawing that I’m then gonna fix later and “make perfect” in the traditional comic book sense of making something “perfect” it’s more the idea that art as we know it in the 20th century, drawing the way I’m drawing is not that unconventional. I’m speaking to a familiarity with drawing like that. It feels natural to me and I just want to cultivate that. That’s how I draw best.

And it makes perfect sense for an autobiographical story like this. So when you’re working that way, since you said you don’t thumbnail or sketch things out or write a script, how much work do you end up having to put in afterwards to figure out the pacing of it or narrative structure? Is it presented here in the book in the same order that you created it?

No, no. It’s shuffled around. So the spread is the unit for me, I always compose the left and the right together, and generally I would draw the left and the right in one day of drawing. Generally I think in 4s and 8s and 16ths, so there’s an inherent timing – 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7-8, 9-10. There’s a rhythm there and I would just shuffle. I would take photographs of the spreads and then have them all in my iPad and I would keep changing the order so that I can see different orders without moving the originals around which are kind of fragile and have lots of tape and stuff and so eventually I made full size color xeroxes of every spread and so then I was really editing and moving stuff around. The text is a separate layer. I would write the notes for the text on the side, and I would have a specific yellow layer of tracing paper and would write the text on top of it, you could read it like a manuscript, a separate layer of text, and I would pull that and change that. The editing was a long process. I drew the whole thing, had it written with notes, and then had to do all of the text by hand on this layer of tracing paper and then see it and then I had to make all of the lettering and that’s on a separate layer. And that’s also because I knew it would come out in French first [published by Éditions çà et là] and so I didn’t do any of the layers on the actual art.

That’s smart.

So it didn’t come out the way I drew it, it’s all over the place. But to me the unit is the left-right, and so you can create an inherent time signature within the structure. I knew it would be around 200 pages so I had 100 spreads, which isn’t that many actually.

When did you start full-on working on this book? Obviously it has interviews from a long time ago, but when did you turn your full focus to this project?

Really December 2016, so then January 2017. Whole winter, spring, summer. So I had a good 7 months of hardcore drawing, every day. I remember I did 138 days straight at one stretch. And then editing and getting the translation back, so it took like 2 years of note taking before the year of actual work, then 6 months of editing and its somehow adds up to 4 or 5 years

There’s that page at the beginning where you say “I started out to write a story for my mother, something to distract her as she got old. But I ended up writing the story for me, something to distract me while she got old” and considering what you just described with your process of making this and arranging it, were you surprised at where this ended up and what story you ended up telling?

Yeah! Haha, sure, yeah. I still want to please my parents and I thought I could make something to please her. But you know, she said she “didn’t love all of it” but that she was proud of me for doing it and that she loved it, you know. We haven’t really talked about it. She sent me a text about it, it was very modern of her. But when I’ve seen her since she hasn’t really brought it up.

Haha. Based on her personality in the book, that doesn’t surprise me at all.

My dad really liked it. And maybe because it’s more of his story, he gets more of a pass because he went through so much. He suffered this stuff so he sort of gets a pass in a way. I mean that his story is easier to tell. My mom’s story is way more nuanced, and gets boiled down to these black-and-white things that are way more nuanced within the family, you know, alcoholism in the family and other stuff. My mom never drank, her family drank. Now that’s real easy for everyone to talk about, everyone’s in programs and stuff, but 20-30 years ago this stuff was never talked about. So things that made life difficult within my family were weird dark secrets that every family has but now society at large has a better handle on talking about these things. But her family just gets boiled down to poverty and alcoholism, really. And her amazing strength and working her way out of that and surviving that. I wanted to make something to please her and get closer to my mom somehow… I’d ask her to tell me stuff about her life or what happened with uncle so and so. She knew this stuff was going into the book but not what shape it would take. A lot of my family knew I was working on this book but I know they’re not going to like it, but I didn’t want to hold back either. Me knowing it was coming out in French first gave me a cushion to deal with that. So I’m a little concerned about it, but they’re great and supportive, they’re old school – not helicoptery. They’re not really that interested.

Will they even read it?

That’s sort of what I’m saying, they will but I’m not sure if they can. A family friend told me they had a hard time just reading it. It’s not easy for the layperson to read comics. Especially this book is a little…

It’s very complex.

I did write the story because 10 years ago I didn’t know how long I would have my mom, and I still have her now and I’m thrilled, and I did make it to distract myself as she got old... it’s hard to watch your family change and get older.

I assume it hasn’t had any impact on the relationship with your mom and dad?

Haha, no no. I think my dad would talk to my mom but my mom… no… unless we’re at a function together and maybe she’d nod her head at him or wave hello. I had an art opening in 2011 and my dad said hello to my mom and my mom just kind of smirked at him and turned her head.

Well in regards to the relatability of it, since you said you wanted to get away from it being a story just about your family, I do think it’s so much more than that. I wanted to ask, how important actually is Pittsburgh to this book? Cause to me this isn’t a book about Pittsburgh, it’s a book about home and memory for anyone… that intangible idea and impossible to access feeling of “home.” And trying to make sense of those feelings. One of the parts that struck me the most emotionally in the book is when your dad reveals to you that he had indeed planned to leave your mom for a while but was waiting til you moved to California, and the wordless pages following that, and then you saying that this information surprisingly “cuts deep” despite the years. That pain is so relatable and real for everyone who remembers being young. Cause when you’re young, life and reality and relationships and experiences just feel kind of like a fixed and sure thing. And when you get older and these “reveals” are made and a light is shed on what was actually happening “behind the scenes”, no matter how old you are, that is hard to hear about. It’s devastating.

That’s interesting, it just struck me – that feeling that those relationships were fixed in place, that’s Pittsburgh for me. Like being from Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh’s identity was a fixed-in-place thing. Like a blue-collar upbringing. Especially an Italian Irish Catholic upbringing is a very specific identity that doesn’t hold any weight really in the Pittsburgh that exists now. The kids that live here now don’t really know that this was an industrial town with people that worked in factories, and what that does to the people that have lived here and grew up in that environment. I think about it a lot. It’s kind of relatable, like a rustbelt mentality, but it’s a very different background than other parts of the country and the world. But the change that has been wrought in the last 30 years… can people even remember what working class meant, when it didn’t have a negative stigma to it? People have said to me “don’t say blue collar, say working class” cause there’s some weird stigma about it now, which rubs me the wrong way. So growing up here, we weren’t really middle class, we were almost middle class. You see it in weird 70s movies, it’s like a cartoon version of what it was. These differences of being Irish American or Italian American or Polish American, these people were all factory workers living in different sections of town but were all sort of in the same boat. Now there are people moving to my neighborhood buying expensive houses and if you would’ve told me when I was leaving for college that people were moving to my neighborhood I’d say you were crazy, people needed to get OUT of this shithole, industrial wasteland that I grew up in. But then that industrial wasteland fell into ruin and now has been reborn in the 21st century for all these reasons that I won’t talk about because it’ll be too much of a sidebar, so all that…that’s transformed the landscape. I think I’m trying to make a relatable story like you’re talking about that is about family relationships… and the reader brings to that their own experience, but I’m trying to add an extra layer of an immigrant working class mentality. Art didn’t have much of a place where I was growing up. Outside of my household, I mean. I was lucky in Pittsburgh with the family I had, but being an artist or just drawing was frowned upon when I was a kid. It makes me think about how Pittsburgh has changed and so there’s a layering I’m trying to do that’s intuitive. I’m layering the crumbling and reconstruction of my family with the crumbing of Pittsburgh as I knew it and how it’s reconstructed itself.

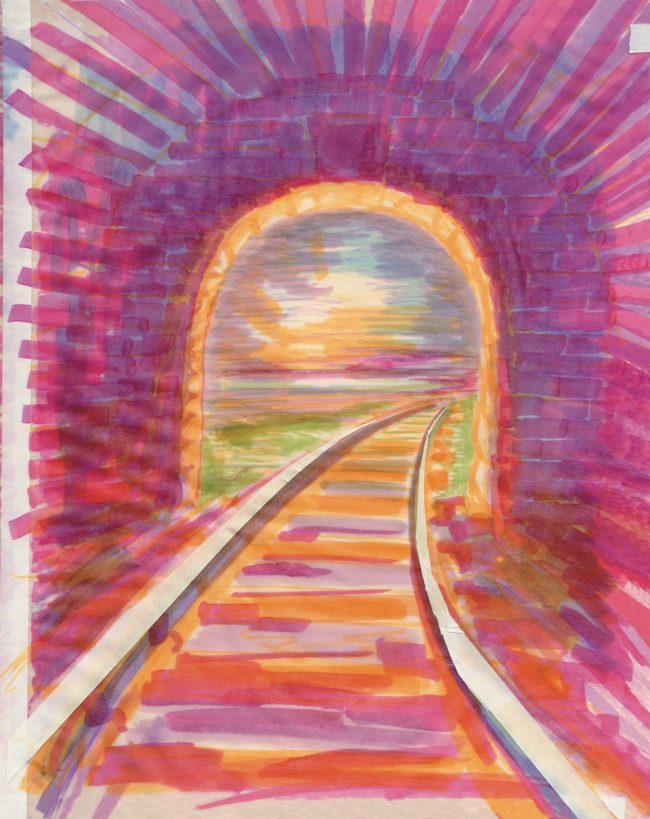

There’s certainly a lot of burning imagery in the book, that’s all in there. Then literally closing with a train leaving the station.

It’s the atmosphere. What’s weird with this book is that with other stories I’ve tried to tell I can talk about the limitation I used to try to make the book and the genre I might have been participating in. But memoir is such an interesting thing because its specific to the person’s family but it’s also this relatable thing, and it’s also specific to where it happened and so I really felt like I was stabbing in the dark and trying to trust myself and push myself to do things that I wanted to do. I don’t like saying it’s therapy but I wanted to bring my family closer, I wanted to tell a story... I like storytellers within families. I think all families have good storytellers if they’re lucky enough to have the kind of family that likes telling stories. You can hear these stories told about you in your presence and you can participate in them in your own way. And that’s what I feel like I’m doing, I’m bearing witness to my family and participating. Someone in France said nicely that they thought that I wasn’t judging my family in the book, that I didn’t judge my parents too harshly in this, and I thought that was an interesting comment.

I think that’s true, I mean at no point did I feel like your mom was the villain in this or that there was any villain at all really. Everyone is so relatable. I mean obviously there are some people we don’t get to know as well, like your mom's parents, but everyone seems very human. I particularly loved Denny’s character. Some of the conversations that you represent with him are so lovely. I want to talk about your dad’s story a bit. I thought it was really interesting that throughout the book you do use a lot of wordless pages and stretch out conversations and scenes, and yet all of the information about your dad's Vietnam experience is told within two pages. It’s also one of the only pages where you use a straightforward grid. And I know you think about that stuff a lot so I was wondering what the intention was behind it. That is just a fucking doozy of a page.

Yeah, thanks. Yeah I used a grid there on purpose and it’s the only time where the text reifies and restates the images really. I might move the action so that the image is shown before the text describes it in the next panel but I wanted to be really specific there. But that’s also an editorial thing. I have to admit that I had something different there. It still showed what I had showed but I didn’t have it in a grid, and it was Dash Shaw who said “you should make this a grid.”

Oh interesting, how come?

He said “you have to make this as clear as a bell. This has to be clear as a bell.” And “show it.” I had more text describing it and less showing it at first. I had like maybe an image or two, the full size image on the left hand side and on the right hand side I had maybe a sequence broken up and not in a grid, and Dash actually said “do Jaime Hernandez here. Just show it.” and he kinda got me on my own philosophy. That’s the great thing about having good editors or readers, and I think Dash is the greatest. He’s such a smart author, editor and everything and I just trusted him enough that I have to cop to that, he forced me to fix that and the reason I think it’s good, better, is because he told me to edit that.

I think it’s so much more impactful because it’s succinct.

Yeah I agree. And to me it’s Jaime but it's Kirby, this tight Kirby focus of showing it. It’s this really intense scene that is alluded to in other places, but I didn’t want to show it. I thought that if I cut away to Vietnam and showed Vietnam it would be too jarring because I wanted to keep it all in Pittsburgh since it’s all memory of Pittsburgh. That’s the only time in the book where it cuts away and shows a different place in a whole scene. It worked.

Doing it that succinctly and directly reasserts the suddenness of the event. When you realize how short of a time your dad was abroad and how quickly this all happened, representing it in this way just makes that even more impactful.

Yeah, and it really was that fast. His whole life changed in mere minutes. Twice. That and when his bunker got shelled. All that occurred during a few months.

It’s horrible. I know you said your dad liked the book, did he talk about this part in particular or how he felt about you representing it?

He didn’t really talk about it specifically. But what he did was… as my dad always is when I go over to his house, he was busy doing something on his desk and being specific about the details, and it was the first time I’d seen him since I gave him the book. He had also texted me saying how much he liked it and how it brought him to tears. So when I saw him he was talking about his paperwork and whatever was going on, and then he said “Yeah your book, it was great, I can't believe how much you remembered, and I really appreciate all the things that Denny said about me” or something. And then he reached into his desk and in his desk he has a stash of Polaroid’s or small photos from Vietnam with a rubber band around them which are always at hand, and he had this one photo with his buddies that died on his desk, and I had never seen it on his desk before. And I said “wasn’t this photo with the others?” and he said “after I read your book I pulled this out and put it out so I could look at it.” And that’s the thing with his story, it’s so terrible, and to just tell it for him or throw context around it and show him as a father, I don’t think he has the capacity to sit down and talk to me about it like a modern father might, but I think he got it. Him showing me those photos was something.

That’s really powerful. Do you feel overall like the process of making this book and finishing it and getting it out there was cathartic? Or was it painful? Was it a release?

Yeah, yeah – It was a release, it does feel better. I have used family stuff and my parents in a subject in my art ever since I got serious about art but you just see authors in their older years making memoirs. There’s often this thing that happens and I thought I never wanted to do that but maybe I was avoiding those things. So sure its therapeutic and meditative, but it feels more like this deep sadness that I had stuck in my nasal passages and in the process of doing the book, that sadness is gone. Not gone, but in the book… it’s released somehow. It’s a relief. I didn’t have anything to prove with this book, I feel good about my abilities, this book wasn’t made in any capacity to try to curry favor with any corner. I made it for me. I didn’t think that my publisher would go for it when I first showed him it.

What does “Never Comes Tomorrow” mean?

You know, it just means something to do with my parents. They’re never going to talk again, they’re never not going to talk again. Tomorrow Never Comes, Never Comes Tomorrow, the dawn never breaks on this thing. You never thought it would never be Pittsburgh but never comes tomorrow.

And you’re never gonna get back there.

Right. It didn’t translate so well in France, I can’t remember how we translated it. But it had a different feel. That was a subtitle. And when we had to come up with a title for the French edition, Pittsburgh organizes it in people’s mind, it helps place it. Never Comes Tomorrow for me was like something about my parents, and some word-play. But maybe it sounds too James Bond-y, haha

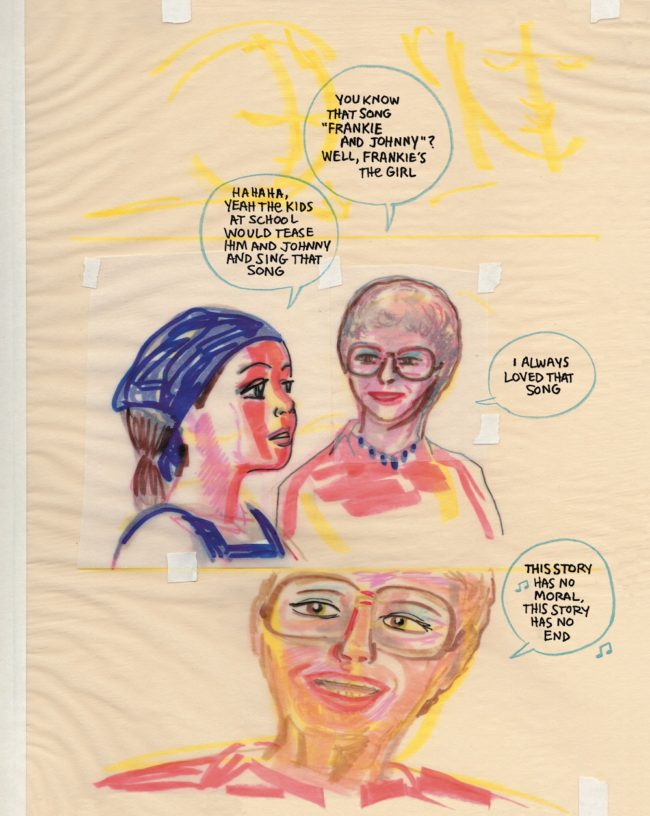

I like it! And also the part where your dad’s mom is talking about the song “Frankie and Johnny” and she quotes the song lyrics saying, “This story has no moral, this story has no end…”

Oh, you’re the first person to pick up on this!

Oh my gosh, I thought that was the most important line in the book!

Thanks! You’re the first person to pick up on this – “this story has no moral, this story has no end…” it’s my story but it’s everybody’s story. I didn’t set out to tell a genre tale that has a moral and has an ending. I’m very pleased that you picked up on it.

It ties to the Never Comes Tomorrow stuff to me. It’s so perfect that that lyric happens to be in that song and that song happens to be where she got your dad's name from.

Oh yeah, and even that story, when my mom told me that my grandma wanted a daughter… my dad’s moms relationship with my mom just made total sense to me. A part I didn’t get to put in there that was my mom went with my dad’s mom to Scotland. My mom was really the daughter she never had. And my grandma was pissed when my dad was leaving her. And when she was much older and I told her my mom’s house had burned down she snapped out of her dementia and was really concerned and talked to me about her for a minute. I appreciate that you zeroed in on it.

Well with those lyrics being about “no end,” I want to ask you about how you decided to end the book the way you did, with your young self just hearing this muffled conversation between your parents.

For me there just a poetry there, it had to have an open ending. I have a return after that but for me the structure of the book, that’s the only time I depict me with both of my parents in the same space all together. That last sequence is the only time we appear all in the same page together. And they’re sort of ghostly drawn. Otherwise I appear with only one of them. And what I say to them rhymes with an earlier scene, there’s a return there. So there’s an open ended structure, I’m trying to have a rhyme or return with things that have happened previously in the narrative, but for me that was a blissful time, young childhood. That’s my memory, I’m drawing the rooms, not much dialogue.

Well and it’s a mundane moment, its beautiful for that, and it just fades into the rest of your life.

I’m just pleased that it reads. I could’ve just written a book that only made sense to me, and I would’ve hopefully achieved being cathartic. But to be able to have crafted something that the general public “gets” but also an informed reader like yourself is really rewarding. It’s hard for me to try to talk about what I’m trying to do with my work without it coming across high handed. I’m trying to push the idea of what is possible in comics and combine that with how its made or presented. So if it read clearly to you or was successful and certain rhymes landed, I’m just really happy with it. I’ve never had the experience of making an artwork like this.

Well I think you’ve really hit something. It’s really fucking successful and I’m totally not just saying this, it’s definitely one of my favorite graphic novels. It’s really strong. I tend to enjoy things that are heavily about memory or trying to figure out how to represent memory and I think you’ve just done it so masterfully. So thanks for making it!

Thank you! You know I have to mention that when you interviewed Chris Ware on stage about memory, I raised my hand at the end and asked him a question about Ben Katchor’s work being a memory of New York. He didn’t get to what I was saying, but I was trying to connect it to an exchange I had had with Chris a different time where he said that when he had seen a study or something where people were drawing things based on their memory, and he said “they look like your drawings, Frank” like “they look like the way you draw” and that pleased me to no end because I just think there is a real connection between drawing and memory and mapping, and his work delves into that and he thought that these drawings that the general public make when they’re trying to remember things look like these naïve drawings I’m making, so when you interviewed him on stage, I think you really figured something about not only his comics but I think comics in general. A lot of comics work in this area but it’s hard to pull off. There’s something about your work in this field and the way you talked about it with Chris and the way he related it with me, it’s in there, it was something I was thinking about a lot.

Yeah there’s lots of comics that deal with remembering things but many of them are very labored and that takes away from it. Your style has just nailed it. Thanks for talking to me about all of this – what’s the plan for the book release, will you be going on tour?

It officially comes out September 17th 2019 from NY Review of Comics, and I’ll be appearing at SPX, Brooklyn Book Festival, CXC, and then I will be at Copacetic on October 5th, and the Strand on October 7th and the Beguiling October 16th.