I cannot read anything these days without finding metaphors for our strange current times, so when I read this story about a gargantuan, noisy potato threatening to crush a small French village, I found it surprisingly relevant. Whistle is French cartoonist Louka Butzbach’s whimsical origin story about his hometown of Fontenay-sous-Bois, a suburb east of Paris. The story begins once upon a time, when “one would ring a friend’s doorbell should one be feeling lonely, and when old shoes were mended, not thrown away.” Nicolino is a young man who works on a potato farm and discovers an inflatable potato (you really have to be there) that’s sucking in air and growing larger and larger.

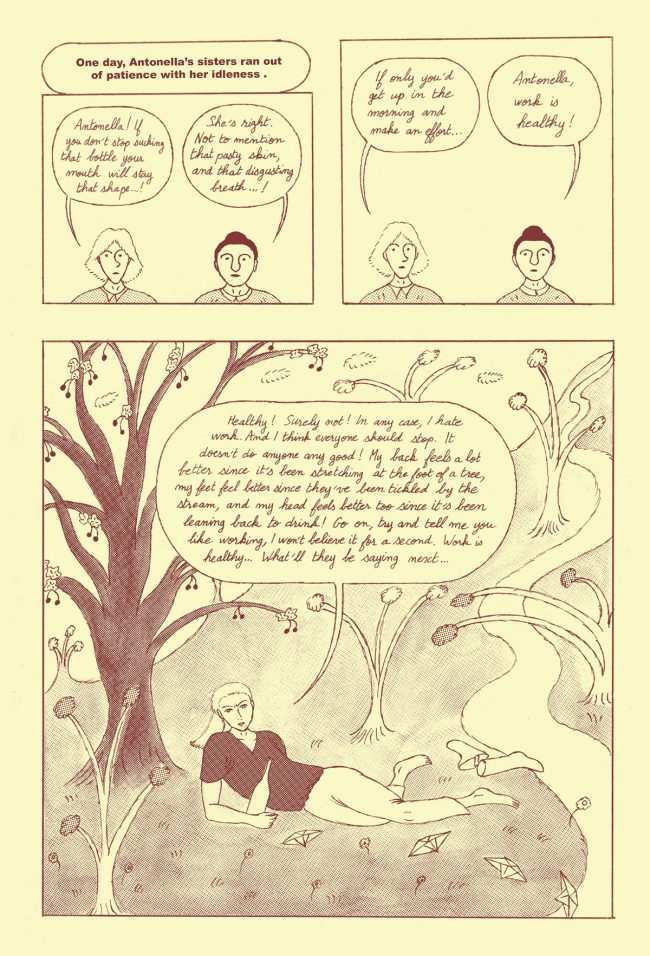

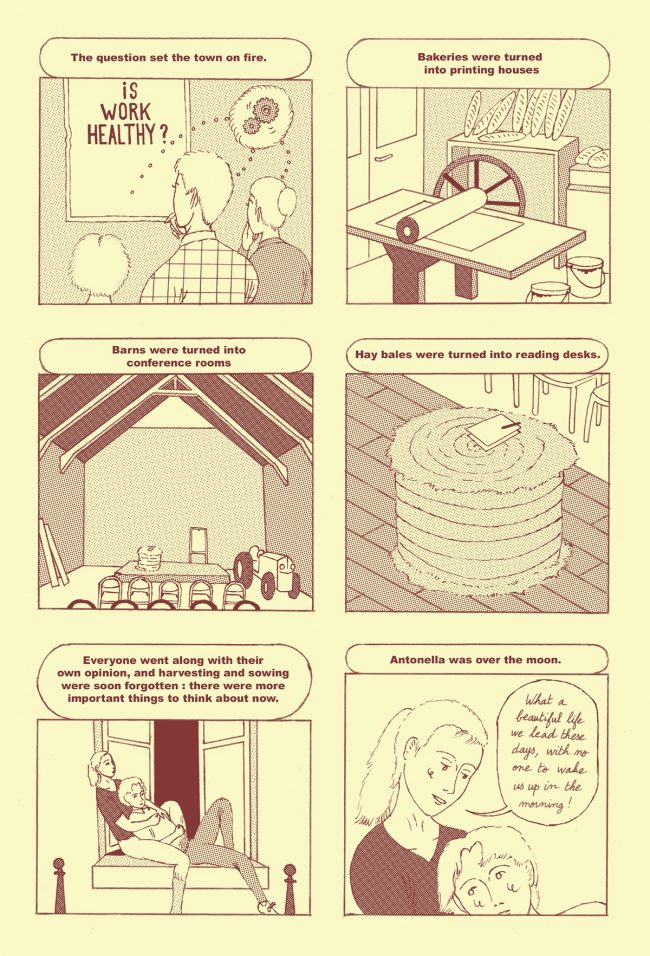

As the potato expands, the story meanders forward, a bit disjointedly at times, but engagingly enough. Nicolino and Antonella, a young lady from a cherry orchard downstream, fall in love at first sight but are separated. Yearning for each other, they both stop working in favor of lying around daydreaming about each other all day (and drinking something fermented from a tree stump, in Antonella’s case). Antonella instigates a village-wide debate: Is work healthy? Should we keep working? Antonella thinks not, and “gobsmacks" her sisters by telling them so. The sisters lie awake all night, little cogs spinning in their thought bubbles.

With their laziness and distraction, the lovers instigate a full-on labor revolution, led by little Enrico, an elfish child sitting cross-legged atop a desk, eating apples, and making flawless arguments: “If work is healthy, why then do I prefer being sick than going to school?” Meanwhile, the two young lovers are reunited, and find they can not agree on the question of labor; while Nicolino doesn’t know what he’d do for the rest of his life if he didn’t work, Antonella can think of plenty ways to pass the time. This debate has really found its feet recently, as so many of us are out of work, examining our role in the capitalist machine, or wishing we could nap in a meadow rather than drag ourselves to an upright position for yet another Zoom meeting.

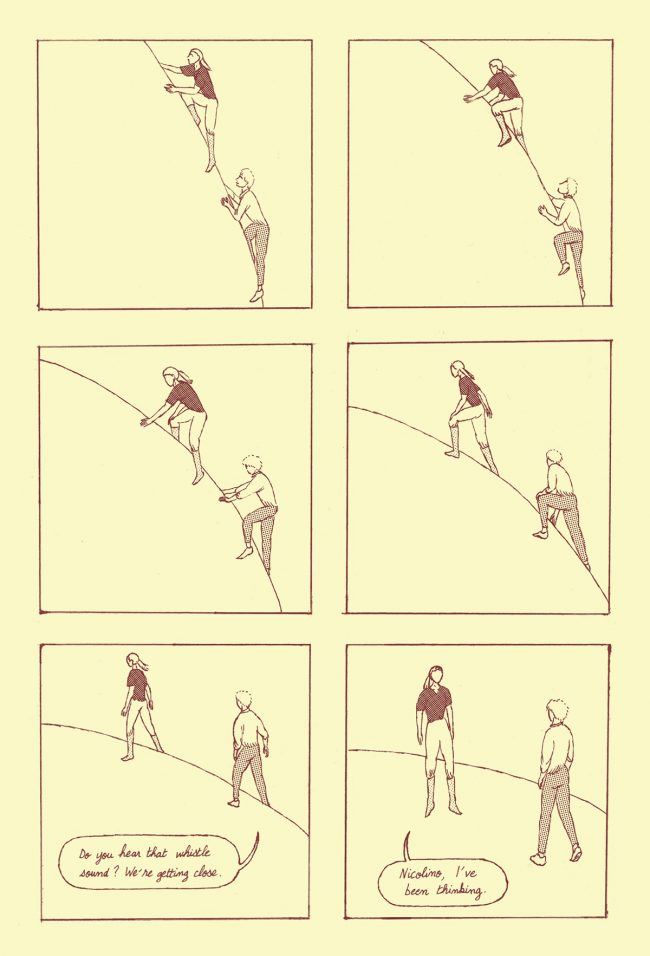

Eventually, the villagers all stop working and neglect to notice the potato, which is by now a giant, whistling orb in the sky that begins to tumble downhill towards the village. Can the potato be stopped? Do Nicolino and Antonella stay together despite their contrary philosophies? And most importantly, does the village determine whether work is healthy? I won’t offer any spoilers; you’ll have to either read the comic or ask a modern resident of Fontenay-sous-Bois while they’re on a smoke break from their 35 hour work week.

This is Butzbach’s first comic in English. His drawing style is naive and un-self-conscious; it is pleasant and serviceable to the story, but without an attempt at being very stylish or polished. There’s something French, romantic, and old-fashioned about the comic’s appearance: the panels are drawn in sketchy, feathered lines, and the dialogue is written in lilting cursive. With sepia lines and Benday dot style shading like a comic of yore, Butzbach draws elongated figures and curving lines with a light, easy touch. The nicest visual is a sequence of drawings that show the interior of the potato, a hazy, toothy cavern full of soft and goopy stalactites.

The translation from French is at times a bit baffling in a charming, otherworldly way (“Whenever he got back to work, he would accidentally dig up his own foot, and digging up his own foot was beginning to seriously threaten his physical integrity”). Somehow this suits Butzbach’s curious, dreamy storyline and visual style, which are in the vein of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, a fellow French author. Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince is another surreal fable, presented gently and a bit obscurely with quiet humor and simple, amateurish illustrations (and surely there is a comparison to be made between the giant potato and Asteroid B-612). There’s a sweet nostalgia in both stories, as we long for a simpler time when “one would ring a friend’s doorbell should one be feeling lonely.” And as we think about the value of our labor, our relationships, and our villages, Whistle is a brief and sweet escape.