There’s a scene approximately a quarter into Weegee: Serial Photographer where Arthur Fellig, the real name of the titular Weegee, fusses over a dead body. A police officer tells us (by telling Weegee) that the corpse belongs to the owner of the restaurant where it was found. His dog, angry or anxious or some combination of the two, stands watch over his corpse. “What?” Weegee asks, “You’re telling me we’ve got to wait for the pound to get near the body?!...” The officer responds by telling us that he “ain’t about to shoot” the dog. “Dammit, I swear, Frank!” Weegee yells, walking out, slamming the door, frustrated that he cannot get the picture of the corpse that he wants. Weegee returns with a wet steak to distract the dog, and so we are spared the sight of any animal cruelty; though, we are left with the sense that Weegee wanted that picture badly enough—if he had to, he would have shot the dog. That is because he suffers from what Sigmund Freud calls “scopophilia,” that libidinal urge that gets off by looking or by being looked at.

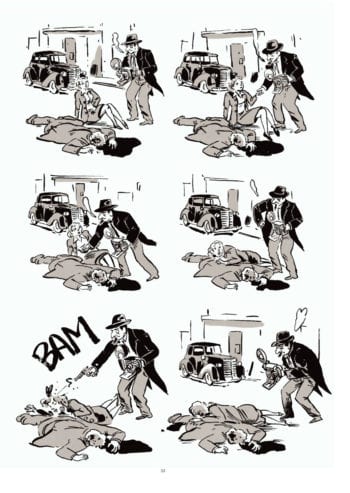

While it’s doubtful that Weegee authors Max de Radiguès and Wauter Mannaert knowingly make this argument about their subject, it’s hard to shake the sense that they nonetheless understood this about Fellig. The book’s first scene introduces us to Weegee. A man has been killed, and his body lies motionless in front of a movie theatre. The lights from the marquee highlight the body, and a crowd looks on in shock and horror. Bystanders in the crowd cover the mouths—as though they are too shocked to close them—and Mannaert draws their eyes so that they appear ready to pop out of their sockets. In the first few panels, Mannaert renders Weegee as a morass of criss-crossing lines that amount to a silhouette and a pair of bulging eyes. It is only by wielding his camera that Weegee—figuratively and literally—distinguishes himself from the crowd (or at least, that is how the scene is drawn). The first thing that Weegee says—to no one in particular, and therefore to the reader directly—is “Got a good feeling about this one…” But, as he inspects the body, something isn’t quite right. The posture, the pose, the lighting, the whole the mise-en-scène: it is, for Weegee, inadequate and unsatisfying. The police haven’t arrived yet, so Weegee manipulates the body, changing its position, moving the man’s hat. In a series of three panels, which Mannaert draws without panel borders so as to underscore the languid, reflective pace of Weegee’s own perspective, Weegee makes tiny adjustments to the corpse, even going so far as to adjust the man’s head with his foot. “Nailed it,” he tells us, holding his hands in front of his face to imitate the viewfinder of his camera.

Images, images, images: everything for Weegee is reducible to the image. If it will make a good photograph, he’ll take it. If it won’t, he’ll manipulate reality until it does. Nothing takes priority over his looking, over his voyeurism. Even his flirtations with Rita, the owner of a local diner, are circumscribed by the language of looking, of voyeurism, of photography. Trying to “sell” herself to Weegee, she tells him “I’m pretty normal, too.” She poses to accentuate the curves of her body. But, its balloon thrust out into the foreground, imposing itself over even Weegee’s body, she says “You can take my picture.” In the panel, Weegee looks apathetic to the proposal. And when she says “You can take my picture,” by the next panel, Weegee is smiling and grabbing for Rita’s body. He has made himself so obsessed with photographs, these malleable imitations of reality that afford him God-like control (in making them) and omniscience/omnipotence (in consuming them), that he cannot excite himself sexually without appealing to them.

Images, images, images: everything for Weegee is reducible to the image. If it will make a good photograph, he’ll take it. If it won’t, he’ll manipulate reality until it does. Nothing takes priority over his looking, over his voyeurism. Even his flirtations with Rita, the owner of a local diner, are circumscribed by the language of looking, of voyeurism, of photography. Trying to “sell” herself to Weegee, she tells him “I’m pretty normal, too.” She poses to accentuate the curves of her body. But, its balloon thrust out into the foreground, imposing itself over even Weegee’s body, she says “You can take my picture.” In the panel, Weegee looks apathetic to the proposal. And when she says “You can take my picture,” by the next panel, Weegee is smiling and grabbing for Rita’s body. He has made himself so obsessed with photographs, these malleable imitations of reality that afford him God-like control (in making them) and omniscience/omnipotence (in consuming them), that he cannot excite himself sexually without appealing to them.

In theorizing the “male gaze,” film critic Laura Mulvey categorized Alfred Hitchcock as the scophiliac par excellence. Ironic, then, that Weegee appears to us like a Hitchcock character pushed to their psychological limits, as he, unlike Hitchcock’s voyeuristic characters, grapples with his own own repressed desires. His obsession makes itself known to him in a series of dreams, which see him photographing a dead body only to become the victim’s killer. While Mannaert renders the book with thin lines, heavy hatching, and conventional layouts (intuitive, featuring panel borders, etc.), these dreams appear differently. In one, the layout appears to resemble that of the book’s other pages (simple, intuitive, easy to follow), it lacks panel borders. What’s more, the compositions are much sparser here those that take place in the “real world,” and the lines themselves are slightly, but noticeably, heavier. There is a little hatching, but no cross-hatching. In another scene, this time a daydream, Weegee himself is rendered as an increasingly opaque smear of black ink and abstract detail; the body, however, remains “real,” that is, Mannaert renders it with the same aesthetic that he uses for the book’s “real world.” The most interesting of these scenes is undoubtedly the first. The final panel of this particular dream sees Weegee peering from behind the camera; he looks unwell, as though he recognizes the obscenity of his dream acts, and he both cannot stop and cannot bear to keep watching. In the next panel, he wakes in fright. He vocalizes rather than speaks, letting out a disoriented “Ugh!”

In theorizing the “male gaze,” film critic Laura Mulvey categorized Alfred Hitchcock as the scophiliac par excellence. Ironic, then, that Weegee appears to us like a Hitchcock character pushed to their psychological limits, as he, unlike Hitchcock’s voyeuristic characters, grapples with his own own repressed desires. His obsession makes itself known to him in a series of dreams, which see him photographing a dead body only to become the victim’s killer. While Mannaert renders the book with thin lines, heavy hatching, and conventional layouts (intuitive, featuring panel borders, etc.), these dreams appear differently. In one, the layout appears to resemble that of the book’s other pages (simple, intuitive, easy to follow), it lacks panel borders. What’s more, the compositions are much sparser here those that take place in the “real world,” and the lines themselves are slightly, but noticeably, heavier. There is a little hatching, but no cross-hatching. In another scene, this time a daydream, Weegee himself is rendered as an increasingly opaque smear of black ink and abstract detail; the body, however, remains “real,” that is, Mannaert renders it with the same aesthetic that he uses for the book’s “real world.” The most interesting of these scenes is undoubtedly the first. The final panel of this particular dream sees Weegee peering from behind the camera; he looks unwell, as though he recognizes the obscenity of his dream acts, and he both cannot stop and cannot bear to keep watching. In the next panel, he wakes in fright. He vocalizes rather than speaks, letting out a disoriented “Ugh!”

In this way, Weegee is an incredible character study that drills down into a provocative facet of a real historical figure. And while Weegee may not be a sacred cow the way, say, George Washington might be, composing a sincere biography of someone that insists that they were psychosexually obsessed with voyeurism—in fact, that the work for which they are known was the product of what would still by many be seen as a perversion—is an impressive and laudable task. But the book breaks down precisely because Radiguès and Mannaert turn away from their own argument. Towards the end of the book, the narrative takes a turn. Weegee tells Marvin, his police officer friend, that it “Don’t matter if I’m there to take pictures of the stiffs. The sun keeps rising on the Big Apple.” He looks at a photograph longingly. This is the apotheosis of his condition, and he has to confront the fact that while he derives a unique pleasure from his photography, his subjects could care less if he was there or not. He has exhausted his eye (both literal and metaphoric) and been made to face the fact that his voyeurism is a purely onanistic (and solipsistic) exercise. After that, Weegee plays the violin in a sequence that is, admittedly, beautifully rendered by Mannaert as a series of dynamic close-ups that overlap one another, the brushstrokes visible on the page.

After that, we jump forward. Time has passed. Weegee has published a book of photographs. He is, in so many words, a big deal. He leaves Rita behind, and he moves to Los Angeles. After embarrassing himself in front of Humphrey Bogart, Weegee freeloads a heap of food, and wanders the streets of L.A. He comes across a sleeping vagrant; Weegee puts his hat on the man and takes a picture. But it is impossible to determine what Radiguès and Mannaert mean by this final moment. At first, Weegee appears to have “gotten over” his obsession. But the final page, which appears to be that final photograph itself, belies that. It seems to say to us that not only does Weegee persist in his unhealthy obsession, but that he believes that he has gotten over it; he has repressed it, rather than confront it. This would explain the incredible pathos of the book’s final scenes. Rather than a wistful character that you root for or are, at any rate, interested in, Weegee ends his own story a sad, lonely character who cannot imagine an experience outside of his own. Worse than that, actually. He cannot even imagine his own experience. He cannot engage with it until it is mediated and made into a lifeless object that he can exert total control over. But maybe that pathetic image is precisely what makes Weegee the perfect figure to represent our age of ever-increasing mediation, distraction, and repression.

After that, we jump forward. Time has passed. Weegee has published a book of photographs. He is, in so many words, a big deal. He leaves Rita behind, and he moves to Los Angeles. After embarrassing himself in front of Humphrey Bogart, Weegee freeloads a heap of food, and wanders the streets of L.A. He comes across a sleeping vagrant; Weegee puts his hat on the man and takes a picture. But it is impossible to determine what Radiguès and Mannaert mean by this final moment. At first, Weegee appears to have “gotten over” his obsession. But the final page, which appears to be that final photograph itself, belies that. It seems to say to us that not only does Weegee persist in his unhealthy obsession, but that he believes that he has gotten over it; he has repressed it, rather than confront it. This would explain the incredible pathos of the book’s final scenes. Rather than a wistful character that you root for or are, at any rate, interested in, Weegee ends his own story a sad, lonely character who cannot imagine an experience outside of his own. Worse than that, actually. He cannot even imagine his own experience. He cannot engage with it until it is mediated and made into a lifeless object that he can exert total control over. But maybe that pathetic image is precisely what makes Weegee the perfect figure to represent our age of ever-increasing mediation, distraction, and repression.