Al Taliaferro isn’t the first person you think of when it comes to drawing Donald Duck. That’s maybe not fair, considering he devoted well over 30 years of his life to drawing the fellow, but it’s nevertheless true.

This is all the more impressive when you understand that Taliaferro drew Donald’s newspaper strip for all that time, beginning in 1938 and stretching until 1969. He had stepped down from the daily strip two years prior, but remained at the helm of the Sundays until he died. Even given the astronomical print runs afforded to Dell's Four Color during Carl Barks’ heyday, the newspaper strip almost certainly had a much larger readership, simply by virtue of being in newspapers. But it would be silly to assert that Taliaferro hasn't been relegated to second fiddle in the comics history of the Disney Ducks. Again, the question as to whether that's fair is another matter entirely. Taliferro did a lot for the characters and their history, and his work for Disney deserves a wider readership. He invented Donald’s nephews, for goodness’ sake. They were introduced in emulation of Mickey’s nephews, who predate Huey, Dewey and Louie by a good few years, even if they’ve been mostly forgotten.

Fantagraphics has just released a new collection of the first three years of Silly Symphonies Sunday strips (later "Silly Symphony" in the singular), containing formative work by Taliaferro, and important work as well. (This is a new, revised edition of a collection that was initially published by IDW in 2016: David Gerstein is the editor of the revised volume, taking over from Dean Mullaney, who put together the IDW collection.) Donald Duck makes his serial comics debut here, in a sequence that ran from September 16 to December 16 in 1934. This saw print in newspapers just a few months after Donald made his first appearance, period, in The Wise Little Hen, the May 1934 animated short Taliaferro very loosely adapts in these pages with writer Ted Osborne.

Taliaferro’s work here is still early in his career - still carrying the unmistakable, inescapable mark of the Disney animation house style. Eventually, just as Barks did, Taliaferro would ease into his own look, less fussy and illustrative than the films on which he was riffing. That’s not to say this is stiff work, not at all. On the contrary, the drawing is very nice throughout, really only falling short when called upon to adhere too closely to design work intended for another medium. A sequence set in Mother Goose Land falters slightly in slavishly replicating the look of the Mother Goose cartoons on which it is based. Taliaferro eventually gets better at translating animation designs to the printed page, which remains an evergreen challenge for cartoonists of licensed material across the industry. Part of the process entails learning to change and streamline those designs when necessary, to make more sense as static images on the page.

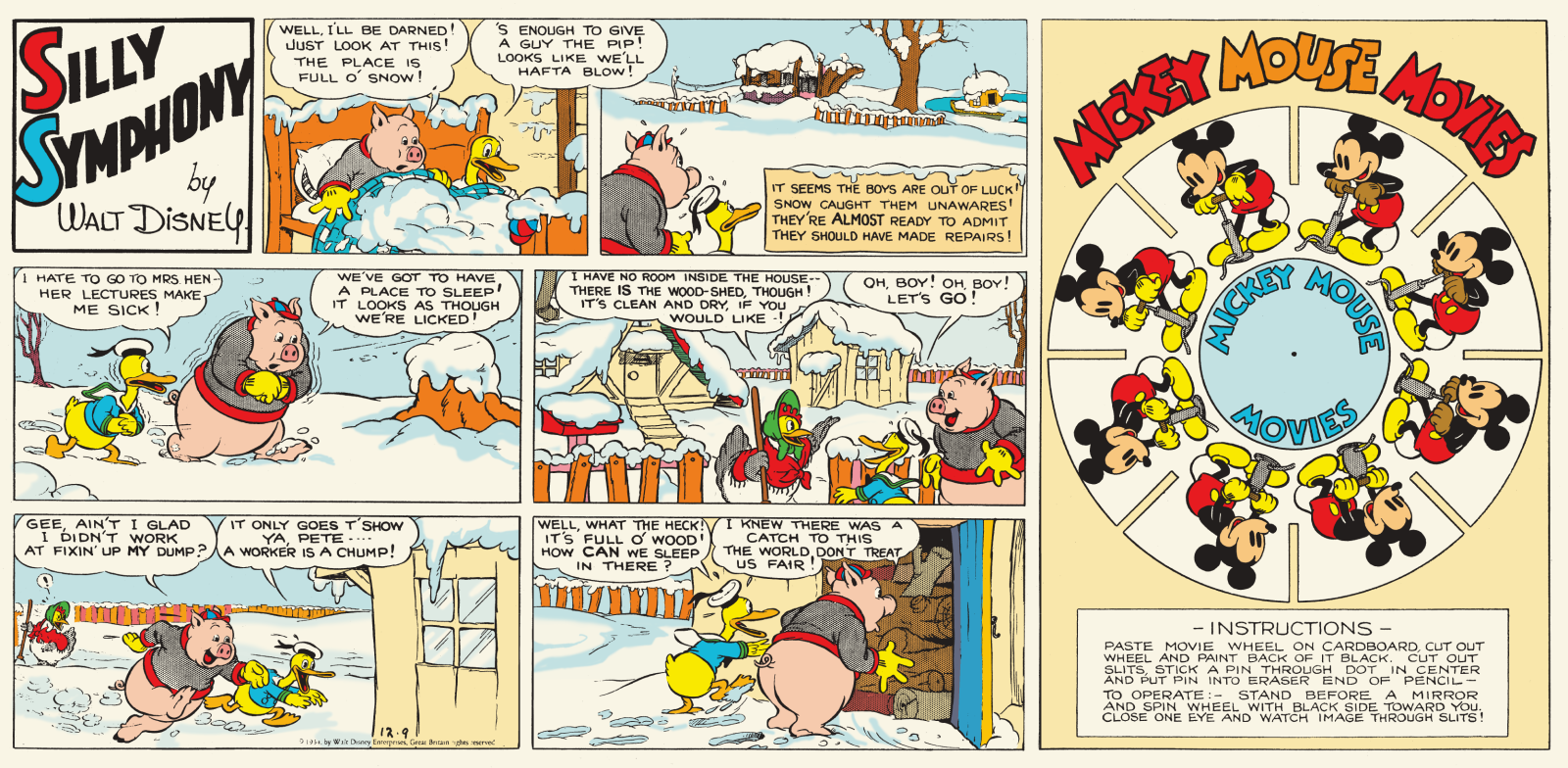

The Donald Duck we encounter is the ancient Donald, a version of the character as distant from the modern specimen as the Superman who appeared in the first run of Action strips in 1938 would be from the iteration of the character who learned to fly just a few years later. And just as the early Batman wore those dainty purple gloves, Donald 1.0 spends his time hanging out with a dissolute fellow named Peter Pig. The two of them share a commitment to avoiding work as much as possible. That doesn't sound so bad, maybe, from the perspective of 2023, when shirking has become a much more noble pastime for the harried professional. But if you've any familiarity with the early Disney, you'll recognize arguments against laziness as perhaps Disney's most strident thematic preoccupation. Hard work isn't merely valorized, it's essentialized: nothing seemed to disturb Walt more than the idea that someone, somewhere, might be slacking off.

Donald is a pretty lazy piece of work. Him and Peter live in a shotgun shack that offers no protection against the elements, and yet they find themselves unable to muster the wherewithal to do the upkeep necessary to stay dry during a rainstorm. (Sounds more like undiagnosed ADHD to me, but what do I know?) They spend the majority of their page time whining about not wanting to do any work - complaining about the unfairness of life that compels them toward anything but to dance around in the sun to the accompaniment of Peter's concertina. If this strip were written today, they’d glued to their PlayStation. Never doubt: laziness is the most fundamental moral flaw possible in Walt Disney's cosmos. And so it becomes Donald’s great Achilles' heel. Even long after this, after Donald evolves and the character comes to inhabit a more expansive psychology, he never loses touch with the basic impulse of wanting to work less. Even if the chosen shortcuts inevitably make him work twice as hard. That's consistent through every iteration of the character.

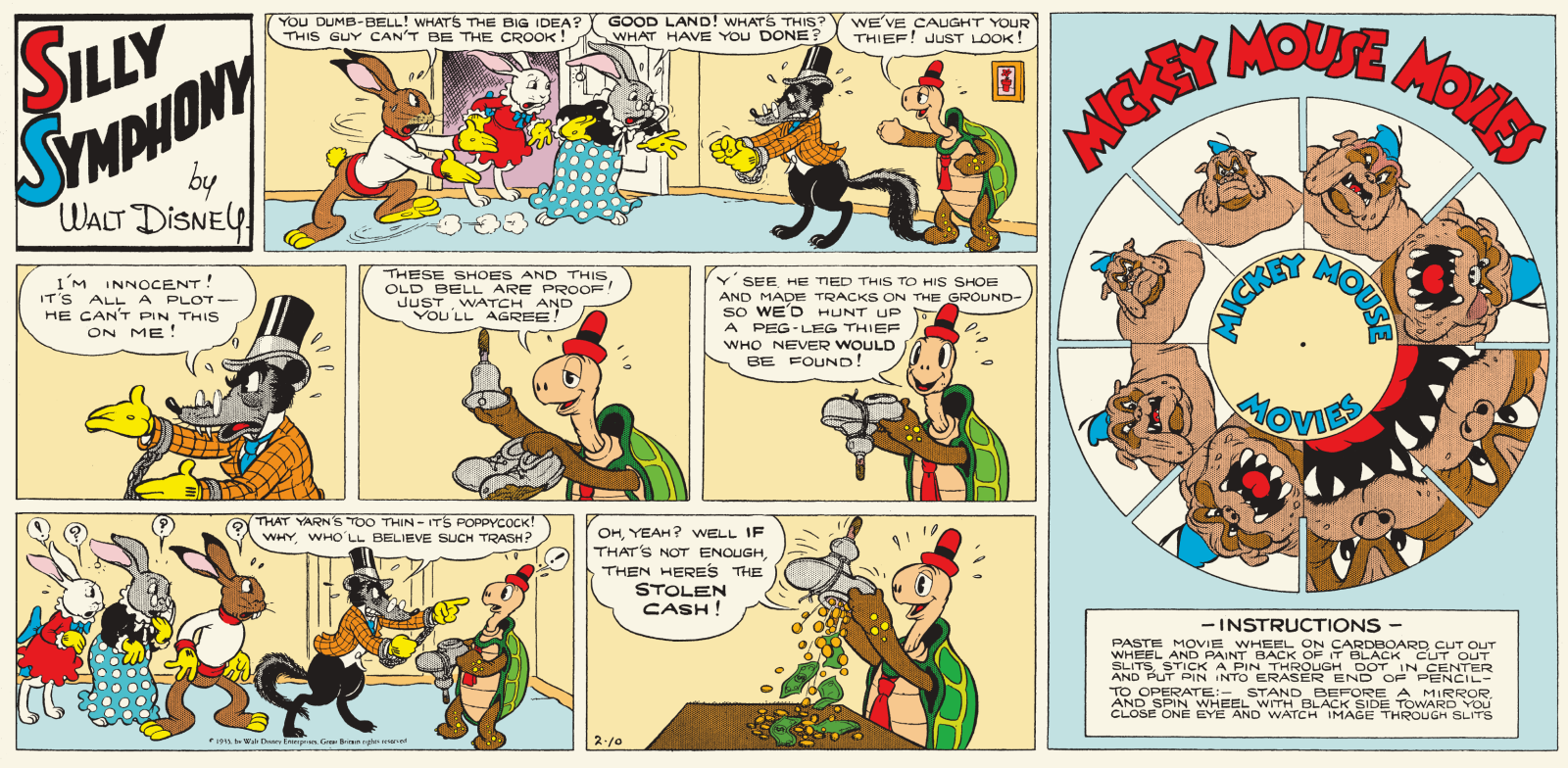

However, despite the cover billing, Donald really only appears for those three months' worth of Sunday strips. The Silly Symphonies animated cartoons were an anthology, with every short introducing new characters and settings. By 1934, the newspaper strip had eased into doing adaptations of then-current cartoons - loose adaptations in some instances, yes, but still attempting some synergy with the screen product. In 1935, The Tortoise and the Hare won the Academy Award for Short Subjects, Cartoons, one of seven Silly Symphonies shorts to do so over the course of the series' existence. The newspaper strip presented a contemporaneous storyline, "The Boarding-School Mystery", but eschewed a strict reproduction of the Aesop fable as presented in the film. The comic strip features the same characters, but working together as detectives on the hunt for a thief. Some liberties were taken to make a longer adventure with these ciphers.

The first two-thirds of the book, however, belong to the continuing adventures of a single character: Bucky Bug. There was some limited crossover between Bucky's stories and the animated shorts was limited—as during the aforementioned hallucinatory journey to Mother Goose Land, a setting previously seen in both 1931's Mother Goose Melodies and 1933's Old King Cole—but, for the large part, the adventures here are unique to Bucky's experience. (If you enjoy seeing Mother Goose characters get read the filth for being useless sons of bitches, Bucky did it here way before Shrek.) Silly Symphonies actually begins with an extended sequence wherein the protagonist lacks a name. The strip solicited readers to mail in suggestions, and the character himself broke the fourth wall to acknowledge the massive pile of letters sent in. Bucky was christened as such by Bernice Sable of Minneapolis, MN, and the comic tells us for her troubles she was awarded an 18-inch stuffed Mickey Mouse.

Mickey doesn't otherwise appear in the Silly Symphonies strips, with a couple exceptions. Mickey and the other more established Disney cartoon characters had their own strip, Mickey Mouse, the daily iteration of which had premiered in 1930, followed by the Sunday strip which launched simultaneous to Silly Symphonies in 1932. Those were drawn by Floyd Gottfredson and are also available in very handsome bound volumes from Fantagraphics. At the time, the strips were sold such that newspapers were strongly encouraged to run them together, with the two Disney strips taking up a whole page of valuable real estate in the Sunday comics supplement. Some Silly Symphonies Sundays conclude with “Mickey Bucks” play money: fake dollar bills with pictures of Mickey and his pals intended to be cut out and traded by kids, and offered as the final panel for many early strips. Mickey would also cross over into Silly Symphonies through the "Mickey Mouse Movies" gimmick promotion: craft projects which accompanied the strip for a considerable amount of time. From June 1934 to March 1935, these took the form of primitive kinetoscopes. Such projects took up a solid one-third of the strip's real estate, and, as with the Mickey Bucks, encouraged readers to cut the page apart with scissors.

Bucky Bug is, in many respects, a close analogue of Mickey. Like the Mouse, the character is an intrepid youth making his way in a cold world, beset by predators and occasionally the recipient of bad advice, but otherwise an upstanding, highly moral individual. He leaves home at the tender age of three weeks—without even a name!—to make his fortune. Bucky falls in with a hobo by the name of Bo, an older bug who teaches Bucky first how to live rough, and then how to settle down and build a homestead. The two wanderers wind up in Junkville, a city made of human garbage and populated by a cast of various insects. Although Bo is a kindly sort, he's also also fundamentally lazy - someone who can't sit still for too long without feeling a primal wanderlust. As he explains to Bucky, in the strip's signature sing-song rhyming scheme: "me feet is itchin', me eyes is dreamin’—me heart is twitchin’! I’m never one t' be settlin’ down.” Very much a workaholic’s conception of homelessness as a permanent vacation, a romantic archetype against which reactionary passions can rail. It’s a vision of the universe in which people are only ever homeless out of choice, because they’re too lazy to care otherwise.

One of reasons the Disney brand became so popular so quickly was that, for all the company's reputation today as the most prestigious blue chip going, in their earliest years they specialized in cheap entertainment freely available during a period of economic turmoil. Unlike now, movie tickets were a relatively reasonable proposition for an afternoon’s diversion, as were newspapers. Putting a crafts project in your comic strip meant something for the kids to do during stretches when the entertainment budget may have been nonexistent. A period defined by breadlines and rampant homelessness was also a time when Disney manufactured endless boosterism for the country’s various bootstrap myths. Surely, as bad as things may get, the only thing stopping you, yes, you from succeeding, is that you just don’t have sufficient pluck. Your fault, Clive. Otherwise, don’t you know it’s just so easy and fun to be a homeless drifter? Which is definitely a choice people make because of deeply-held convictions about how much they don’t want to work, and not a wretched sign of larger systematic dysfunction. A harmful fantasy that some still believe, to judge by the trajectory of urban policy across the country.

Still, with that said, it is nevertheless interesting to note the degree to which, even if the company promoted a wholly wrongheaded understanding of macroeconomic forces, much of Disney output at that time was concerned with real circumstances of economic privation, to a degree that seems practically alien to the sensibilities of modern Disney. A sequence from the later portion of Bucky’s tenure as the strip’s star features the bug returning home to visit his parents, only to find his childhood home being repossessed by the bank - incarnated in the form of a nasty old crow. Bucky and his parents load up their worldly possession onto a wheelbarrow and move down the road a ways, until they find a new plot of land on which to build a house and grow crops. (This confused me, I must admit: if there’s enough free land for anyone to roll down the highway and set up shop at a new lot with minimum fuss, what value would there be in anyone issuing mortgages? The mind boggles.) Losing a home to the bank is just a new opportunity for enterprising individuals to set up a homestead, of course. But that loss was nevertheless a common experience, wrenching apart families and communities across the country during the period.

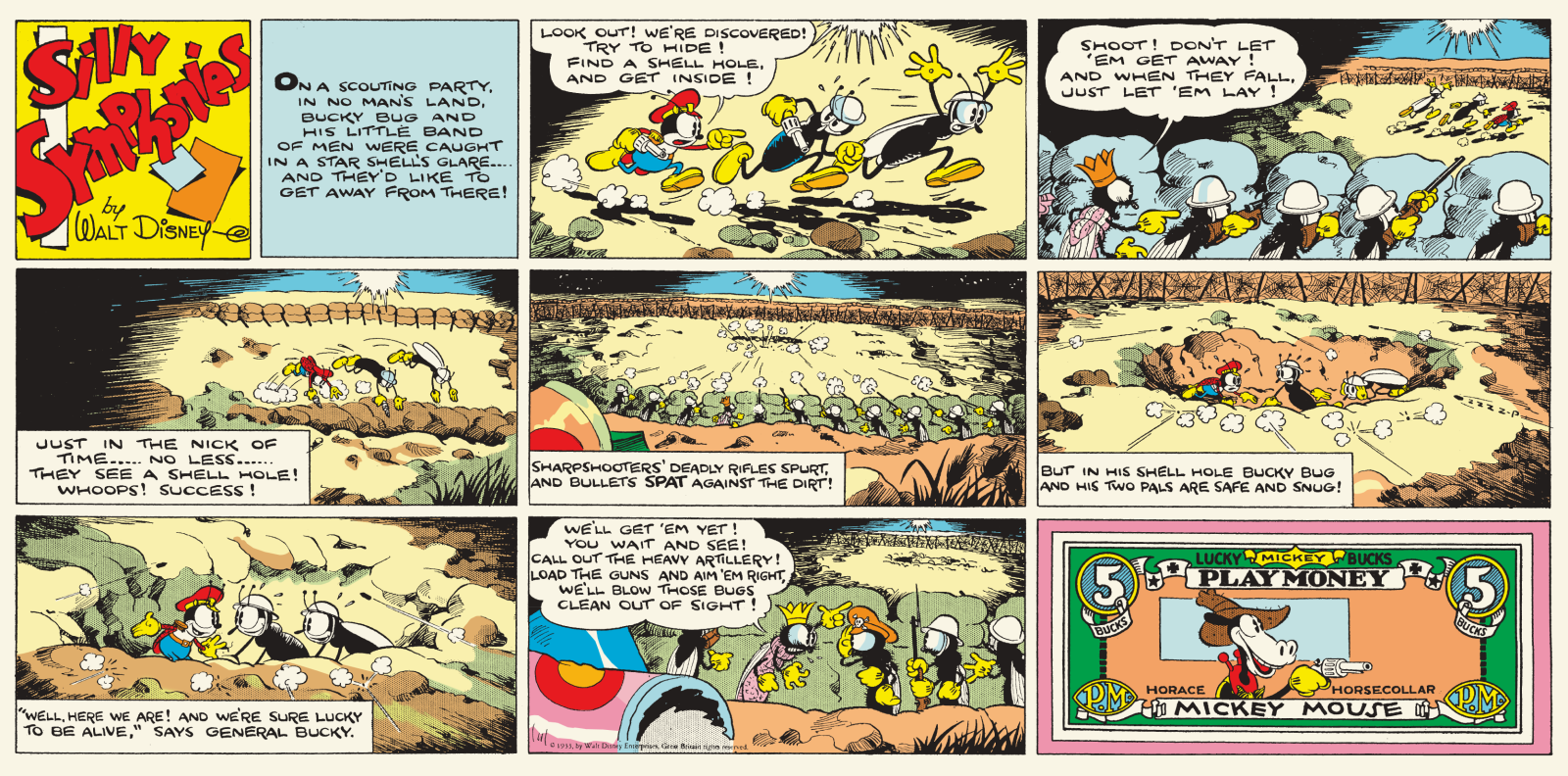

The most interesting stretch of Silly Symphonies is also the strip’s earliest extended narrative, the November 1932-April 1933 war between Junkville and Flyburg City. The story begins when Bucky is granted the title of General of Junkville’s military, a position the Mayor assures Bucky will be purely ceremonial. As soon as he says that, you know the shit's about to hit the fan. Bucky is angling to marry the Mayor’s daughter and is given the position of General as a means of becoming gainfully employed, his previous occupation being that of a tramp. Now, you may suspect that any General so minted because they were the Mayor’s prospective son-in-law would probably not be very good at their job, especially given the high degree of corruption entailed by such a system, and especially given the fact that Bucky is at most a few months old at this point. But when the inevitable occurs, and Flyburg declares war for Junkville’s territory, the Mayor nevertheless trusts Bucky to lead the city’s armed forces. You may at this point expect to see a kind of farce, with Bucky’s inexperience a source of humor. But that’s not what happens at all. He doesn’t do that bad a job, even if he insists he’s making it up as he goes: “I don’t know a thing about wars and stuff, but lots of great deeds are accomplished by bluff!”

Silly Symphonies was mostly drawn by Taliaferro, but it was not written by him. The earliest run of the strip was written by and drawn in collaboration with experienced animator Earl Duvall; Ted Osborne took over scripting duties after co-writing the Flyburg War sequence. Duvall, at least, was a veteran of the Great War, having served in the U.S. Army (that’s according to Lambiek, not information presented in the present volume). With that in mind, the unfolding sequence plays out as a startlingly familiar recitation of the events of World War I. This resemblance could not have been lost on even the strip’s youngest readers, whose parents were old enough to have fought in that conflict. After an initial invasion by territorial nationalists, the defending country begins total mobilization, converting its industrial base to wartime production. Chits are called in with allies. Eventually, deep trenches are dug along the front, territory literally referred to as No Man's Land, complete with the installation of barbed-wire barriers.

I wasn't quite expecting to find such a thorough portrait of mechanized warfare in Silly Symphonies, but that's exactly what we are given here, even down to the Mayor of Junkville poring over ongoing casualty reports - lives spent merely as the price of doing business to hold territory. The Flyburg army brings out poison gas to decimate the Junkville lines, but the timely acquisition of an electric fan foils this plot. Finally, after much death and destruction, Flyburg is brought to heel and made to sign a peace accord which commits them to fully repaying the cost of the war.

An interesting aspect of this sequence: although much of the Junkville industrial base, so to speak, is built on repurposed human junk, the firearms are mass-produced at insect proportions. Their rifles and handguns look just like human specimens but fit for buggy hands. So, yes, throughout the war you see old boots refurbished as tanks, combs as ladders leaning against the walls of the trenches, pills as cannonballs, all that cutesy stuff - but the insects are nevertheless packing real heat.

Given that Fantagraphics has taken over the publishing of these volumes from IDW, with the next volume in the Silly Symphonies series already solicited for December of this year, it's reasonable to suspect they might also eventually get around to the Donald newspaper strip. That was also recently reprinted by IDW, but I don’t think it made as much of a splash as it could have, given the pedigree, and given the degree to which Taliaferro’s reputation still lags behind the likes of Barks and Gottfredson. Fanta reprints a lot of Disney stuff these days. They know how to sell the material to the collectors who want it, or they wouldn’t have put out a hardcover volume of Darkwing Duck. So Al Taliaferro might yet get his moment in the sun.