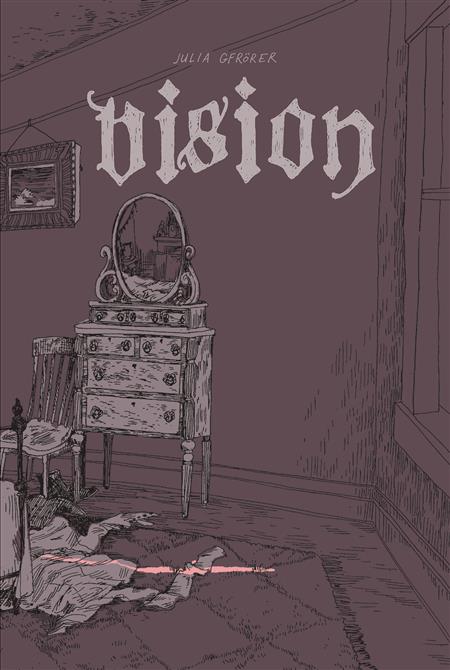

What kinds of erasure of will, desire, erasure of even a sense of one’s body being one’s own, were just routine for women in the 19th century? Would it be worse, too, or better that no other point of view, no other world existed that could promise a way out for you? You were just trapped in history, a horrible little history at that. Perhaps the most disturbing thing to contemplate is whether or not you would you be able to tell you were trapped. In Vision by Julia Gfrörer the ghost that appears in the mirror to the graphic novel’s protagonist, Eleanor, isn’t a source of horror so much as it is a sign that things aren’t exactly right.

The ghost in Eleanor’s mirror likes to see her undress. He loves her. He’s jealous. He thinks she’s beautiful. He doesn’t like it when she’s away for too long. He really doesn’t like her talking to the doctor about the cataracts that are slowly occluding her vision. He is, in other words, a familiarly shitty, possessive boyfriend. Eleanor should leave him (should such a thing be possible with a ghost), and she kind of knows it, too. The ghost, though, seems to be one of the few aspects of Eleanor’s life that represent some kind of comforting stability. In an otherwise spiraling life trapped in a house with her brother and his ailing wife, he/it offers something positive to her, even if it’s also poisonous.

Gfrörer’s breezy, wistful linework gives some evidence to the impermanence of the world Eleanor lives in. Gfrörer’s lines almost seems to move, as if all the details of the old Victorian house Eleanor and her family live in, might shift at any moment when one’s back is turned. The feeling of uncertainty, of not totally being sure what one is looking at, until it moves, strengthens a narrative that is more about a world creeping in on you at the edges than about outright horror.

Gfrörer finds a level of detail that is unsettling while still being bearable: medical blood-letting alongside self-inflicted cutting; a maid with a bloody nose, a couching of a cataract – one of the oldest practiced surgeries – that still makes one squirm imagining it. On top of this Eleanor’s penchant for recreational laudanum is enough to make one wonder how any woman from this time could have stood on her feet, never mind the predations of her brother or the constant distress and accusations from her sister-in-law. Eleanor’s life is one of unremitting, low-intensity suffering. One would think the ghost in her mirror asking her to let it watch her masturbate would be some kind of last straw. But being recognized as a sexual being when the alternative is to exile sexuality from life entirely comes instead as a kind of gift. As with The Yellow Wallpaper the supernatural might be the only name that can be given for the unnamable wrongness of the world.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the graphic novel is Eleanor’s relationship with her sister-in-law, Cora. Confined to her bed, Cora suffers even more totally than Eleanor, yet rather than finding any solace in a relationship between women, she is condescending to Eleanor as she lies about her to her brother. Accepting the limits of the known world, Cora’s vision of the world is a dark pit to crawl into.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the graphic novel is Eleanor’s relationship with her sister-in-law, Cora. Confined to her bed, Cora suffers even more totally than Eleanor, yet rather than finding any solace in a relationship between women, she is condescending to Eleanor as she lies about her to her brother. Accepting the limits of the known world, Cora’s vision of the world is a dark pit to crawl into.

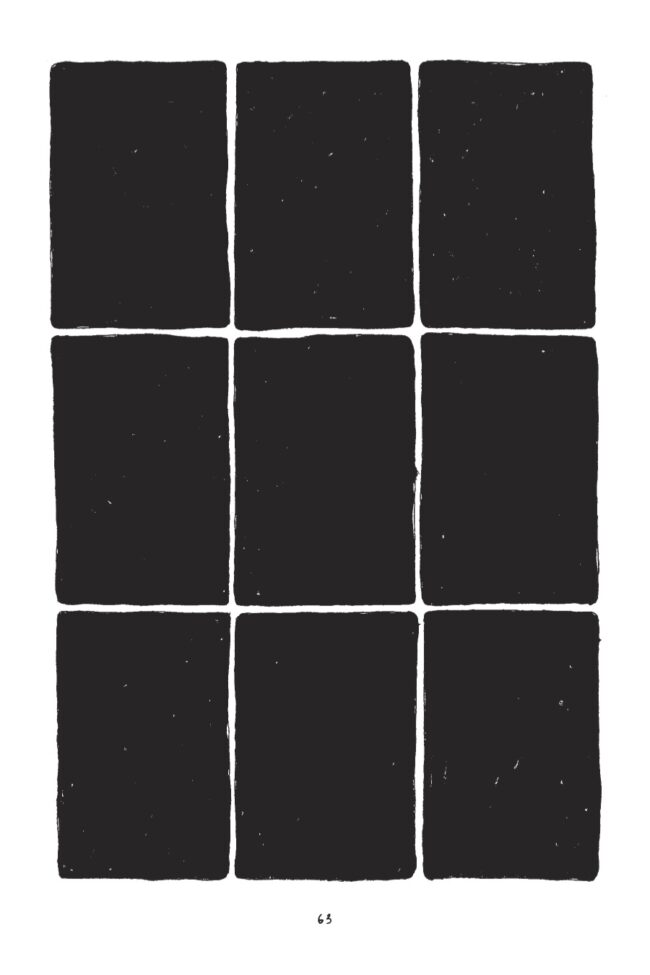

Gfrörer sticks to a nine-panel grid throughout. The regularity emphasizes the unexceptional character of even the worst of what transpires, as time continues in lockstep. The sole exceptions to this are the blacknesses of laudanum-induced sleep. The grid remains, but the accumulation of darkness helps to change the pattern of relentless appearance. The darkness is the only relief to Eleanor from the procession of daily horrors. It is little wonder that she flees to it.

Still, the same pattern grid which makes the horror quotidian, renders the narrative oddly flat and affectless. Stuck within the grid, it seems almost incapable of building in magnitude even as the pace slows and quickens. But for the occasional relief of the blackness of unconsciousness, Gfrörer offers no way out for her narrator, and even the occasional outlet – Eleanor’s relation with the ghost or with the doctor that treats her cataracts – eventually proves incapable of moving the narrative from its inevitable course and they gradually recede into the past. Not that I knew where this was going, but it certainly wasn’t going to be good. Trapped. Trapped inside a house, unable to swim free from the whirlpool of deteriorating family romance, what other way out is there? It makes it clear how much substance abuse is a kind of magical thinking, an opening of some new faculty of perception, a doorway into another world, a cracked mirror that tells you what you want to hear but doesn’t stop when you’ve had enough. But, of course, all that self-harm and self-destruction doesn’t actually produce magic, just harm. The world is what it is what it is. It doesn’t stop, you just might be able to close your eyes.

That’s dark, and while Gfrörer no doubt intends this – to leave us haunted by a narrative that has no resolution or hope of it but the dark page – nonetheless you do hope for more, some cataclysm, something to punctuate time, something other than the slow fading away of consciousness. In many ways, it’s more honest than the kind revisions of history seen in something like Lovecraft Country, which makes horror an ally to righteousness by granting the oppressed some victories – though long after the fact. Vision is precisely what’s not in the book, but it’s not a failure of imagination. That’s the point. It’s just not a happy one.