Why not talk about vampires for a bit? That’s something we can do, still, as free persons.

We have gathered here today to discuss a new comic book adaptation of Vampire: The Masquerade - venerable gaming institution for twenty-nine years - subtitled Winter’s Teeth. I’m not familiar with the game, never having played any role playing games on account of never having had enough friends. (My one tabletop gaming vice was always Magic: The Gathering, but I could never find anyone to play that with, either.) But I do from the prevalence of vampire LARP groups during high school that Vampire: The Masquerade hit its intended audience like a ton of bricks.

Because - big shocker, I know! - people fucking love vampires.

We’re left with a question of adaption. Although I’m not a role player I’ve certainly come across my share of IP taken from games, as well as the frequent dissatisfaction that accompanies same. There’s something in the nature of a game, especially one weighted heavily around social interaction and storytelling, that doesn’t want to be whittled down into one little box. A game is an open-ended experience in a way that a book just can’t be. I don’t think it’s pejorative to point out that comics can’t do what games do, any more than to point out that comics are a poor medium for broadcasting music.

So what can comics do? What does this comic do?

Winter’s Teeth introduces the reader to Cecily Bain, a vampire enforcer based in the Twin Cities. She’s got a shit job that partly consists of murdering people who find out vampires are real, at the behest of the upper crust vampires who run the joint. I emphasize the phrase “murdering people” to highlight the way in which the book intentionally wrongfoots the reader - we first meet Ms. Bain while she’s at work, sadistically teasing a woman before killing her, for the crime of breaking a rule she didn’t know. It’s a very effective introduction, for a character the reader will never be expected to sympathize with. And then you turn the page, after the murder and realize, oh, wait, that’s the protagonist.

The comic has already done something very important, inasmuch as I have been informed that none of the characters who I will be expected to sympathize with are actually sympathetic in any way. As a reader I don’t know really what to do with this information. It’s an effective gambit, certainly, for which I must doff my cap at Tim Seeley, because he actually succeeded in surprising me there.

Was it a pleasant surprise? It certainly did what I imagine the game is designed to do, which is put the audience into the mind of a vampire, inviting them as vampires to indulge entirely novel and diabolic incentives. The vampires are the protagonists here, which is hardly new territory, but perhaps notable in terms of the fact that the original Masquerade setting was published a long time ago. The vampires are also citizens of an ancient secret nation of immortals, regulated according to laws and customs that are dictated by high-born nobles. There are other supernatural races, too, who appear in various subaltern states in relation to the aforementioned aristocratic vampires.

Was it a pleasant surprise? It certainly did what I imagine the game is designed to do, which is put the audience into the mind of a vampire, inviting them as vampires to indulge entirely novel and diabolic incentives. The vampires are the protagonists here, which is hardly new territory, but perhaps notable in terms of the fact that the original Masquerade setting was published a long time ago. The vampires are also citizens of an ancient secret nation of immortals, regulated according to laws and customs that are dictated by high-born nobles. There are other supernatural races, too, who appear in various subaltern states in relation to the aforementioned aristocratic vampires.

More recent franchises, such as Laurel K. Hamilton’s Anita Blake series (est. 1993), Charlaine Harris’ Southern Vampire Mysteries (2001, later adapted as HBO’s True Blood), and even Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight (2005) have all dipped their toes in similar waters, in terms of offering vampires as sympathetic and conflicted protagonists while also focusing on the internecine politics and rule making of underground vampire societies. I’m sure someone who actually paid attention to anything other than blockbuster franchises could construct a more informed timeline, but just my educated layman’s eyes can see a clear progression from Anne Rice’s vampire mythos (Interview was 1976!) to recent visions of vampire society and government. Gone from these fantasies is the image of the lone vampire as a powerful, occasionally sexy threat to be vanquished, replaced with rule-bound bureaucratic revenants and conscience-stricken failspawn.

I don’t consider myself much of a vampire person, in truth, but I do have a lot of affection for Rice’s vampire books (at least the early ones). And I still struggled with those books for much the same reason I find myself struggling to really embrace Winter’s Teeth: vampires are terrible monsters and any extended narrative attempting to create some manner of sympathetic protagonist is going to have to deal with that, probably as a matter of primary importance. Rice solved the problem, as many writers before and since, by embracing glamour and style. You’d want to be a vampire too if you were gorgeous and knew how to dress well. One must do something to offset being a disgusting supernatural parasite condemned to eternal hunger.

Which brings us back to Winter’s Teeth, and Tim Seeley’s rather clever surprise. And it was clever, too, even if it didn’t work for me. The reason it didn’t work for me was, I think, fairly inextricable from the premise: I didn’t much care for being given a vampire’s perspective when the perspective was so sad. Cecily Bain is trapped working for bosses she doesn’t like and who don’t like her, doing a job that consists of “murder.” The story offers us a sympathetic wrinkle in Cecily’s sister, suffering from Alzheimer’s, dependent on Cecily to pay for at-home support. This is mildly novel, inasmuch as vampires are often portrayed as emotionally disconnected from their humanity. But honestly . . . it kind of just makes it worse for me that the vampire has a sympathetic hook? Speaking as someone currently taking care of a declining parent - and conscious every day of the gap between what I can provide at home and what could be provided with greater financial resources than my country is willing to supply - I can attest to the fact that I would do many things to maintain his care but I would hopefully stop short of murder.

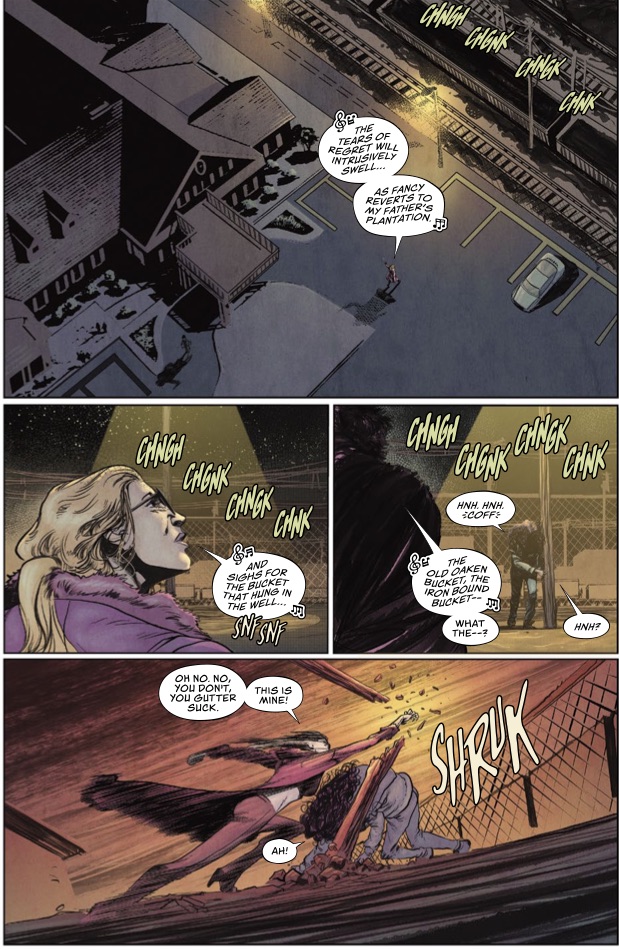

Perhaps the note only rings false for me. But it’s worth pointing out, inasmuch as the book goes out of its way to emphasize the significance Cecily places on family ties, and how important it is that she still feels at all. Later in the story she crosses paths with a newborn vampire just learning how to deal with sudden violent changes. They slug it out for a few panels before Cecily takes Alejandra home and starts to bond. She’s going to need to be protected, and there’s your hook for the rest of the series. Sad vampire makes new family.

Tim Seeley has come in for a great deal of praise in recent years, primarily for the improbable feat of selling readers on a temporary direction for Dick Grayson as international superspy. It certainly didn’t strike me as a profitable direction at the time, but if people in the industry actually listened to me Automatic Kafka would be up to #215. On account of the fact that I dropped out of being even a semi-professional industry watcher a few years back I missed the detail that the guy who wrote those comics was also the guy behind Hack/Slash, a book I rather enjoyed whenever it happened to cross my path. (What can I say? I’m bad with names.) Hack/Slash was a self-aware horror pastiche with just a bit of old fashioned cheesecake thrown in for good measure. A 90s throwback in the very best way - I say that with great affection, as a 90s throwback myself, as well as someone who shares a soft spot for slasher flicks of a certain vintage.

The book’s main story is illustrated by Devmalya Pramanik, a name completely unfamiliar to me before reading this book. My issues with the premise of the book should not obscure the fact that this a very nicely drawn comic book. I would not in the least be surprised if this guy found himself poached by a larger concern before too long. Maybe he already has! He doesn’t cheat on backgrounds or three-point perspective so he’s already doing better than most.

The book’s main story is illustrated by Devmalya Pramanik, a name completely unfamiliar to me before reading this book. My issues with the premise of the book should not obscure the fact that this a very nicely drawn comic book. I would not in the least be surprised if this guy found himself poached by a larger concern before too long. Maybe he already has! He doesn’t cheat on backgrounds or three-point perspective so he’s already doing better than most.

There’s a backup feature, “The Anarch Tales,” introducing us to the vampire demimonde, a group of revenant lumpenproles dependent on scraps and piecework in order to sustain themselves on stolen blood. Written by Tini Howard and Blake Howard, it expands on the themes of the lead tale by showing the bottom rung of the undead ladder. The backup was drawn by Nathan Gooden, in the same vein (har) as Pramanik’s lead albeit slightly more cartoony figurework. The whole thing is colored by Addison Duke. The lead story finds a balance between shades of black and darker pastels, though the backup suffers a bit from the “Vertigo Browns.”

Winter’s Teeth wasn’t really my bag but it is was very readable. Whether or not you enjoy it might have a lot to do with whether or not you know the source material: I didn’t, and what exposure this book gives me to the world of Vampire: The Masquerade doesn’t argue for further investigation. If you’re already on the hook, I can’t imagine you wouldn’t be pleased with what is from all indications an affectionate treatment of a beloved franchise. Almost thirty years is a significant achievement, certainly more than Automatic Kafka got.

There’s a missing element to Winter’s Teeth, and I think that element is a playgroup of enthusiastic friends. When I thought about the book it occurred to me that all the elements which seemed to me to limit the book’s narrative - the politics, the network of obligations, constantly having to make the best choice of bad options - those are all things that would work really well in the context of a game. Makes sense. Personally . . . I like my vampires more in the way of super-villains, singularly charismatic individuals unmoored from any conventional morality, and certainly above such petty concerns as bureaucracy. Marvel’s Dracula is half Bram Stoker, half Christopher Lee, and half Dr. Doom - that’s why he’s the best Dracula, and any man who says different I will fight in the parking lot. Lestat got to dress in French ruffles and be a rock star.

If I woke up a member of the undead and you told me that not only would I have a job, but I’d also have a shitty job with shitty bosses who would treat me just like bosses treat me now, and that my shitty job would be preying on people who had it worse than me . . . that’s no game, that’s just capitalism. An interesting idea, certainly, and thematically rich, but a tad grim for my taste. Even in our fantasies we are still bound to serve by coercion and debt. In the words of the Bard, sheeeeeit. If I woke up a member of the undead and you told me the future was just more fucking rat race bullshit - and not only that but I’d be saddled with a fucking conscience of all things - I’d stake myself to the lawn and greet the sun smiling.