Rutu Modan’s books always sound medicinal: a man tries to find his father, who may have been killed in a suicide bombing; a woman and her grandmother travel to Poland to recover some family property lost during the Holocaust; an archaeological dig takes place on the border between Israel and Palestine, mirroring issues in the region. But when you read them, they’re a joy, not a lecture. Tunnels, the third plot summarized above and her most recent book (the other two being Exit Wounds and The Property), is the same. It’s not exactly a romp or a farce, but it has elements of those things, with revelations and ridiculousness seeded and then revealed with a flourish. It is, above all, fun to read, which doesn’t mean that it’s not also meaningful.

All Modan’s books (I re-read the earlier two to compare them with Tunnels) are about family secrets and shames and, by extension, national secrets and shames. The characters in them don't directly stand in for countries. They're not emblems. But their movements and machinations do translate the bigger scale of national relations and politics to the smaller scale of family relations and politics. They show the concrete results of policy, especially in the ways that individuals bend themselves around and through larger events. Humans are always looking for a loophole, an advantage, an angle, primarily for themselves but sometimes also for their nation. Modan sees this clearly and moves her characters around to show it without judging that tendency. She’s amused, not horrified by the roughness with which her characters treat each other and the ways in which they use one another for gain.

In contrast to that focus on fear and betrayal, light is a huge factor in Tunnels, especially the blue light that cell phones and laptops shed on people's faces. Modan renders it gorgeously and clearly, especially in contrast to incandescent light and daylight. Color has always been important in her work, but this book’s new approach to light as well as color makes us conscious of our own eyes and how they work, especially when characters late in the story are trapped in darkness with a rapidly draining cell battery. That light is precious. Modan also makes the eyes of her characters differently in this book than she has previously: round, cartoony eyes with a bunch of white space inside them, whereas before she just used dots and lines. They're not more emotive, but they do make her work look a little more cartoony and more her own.

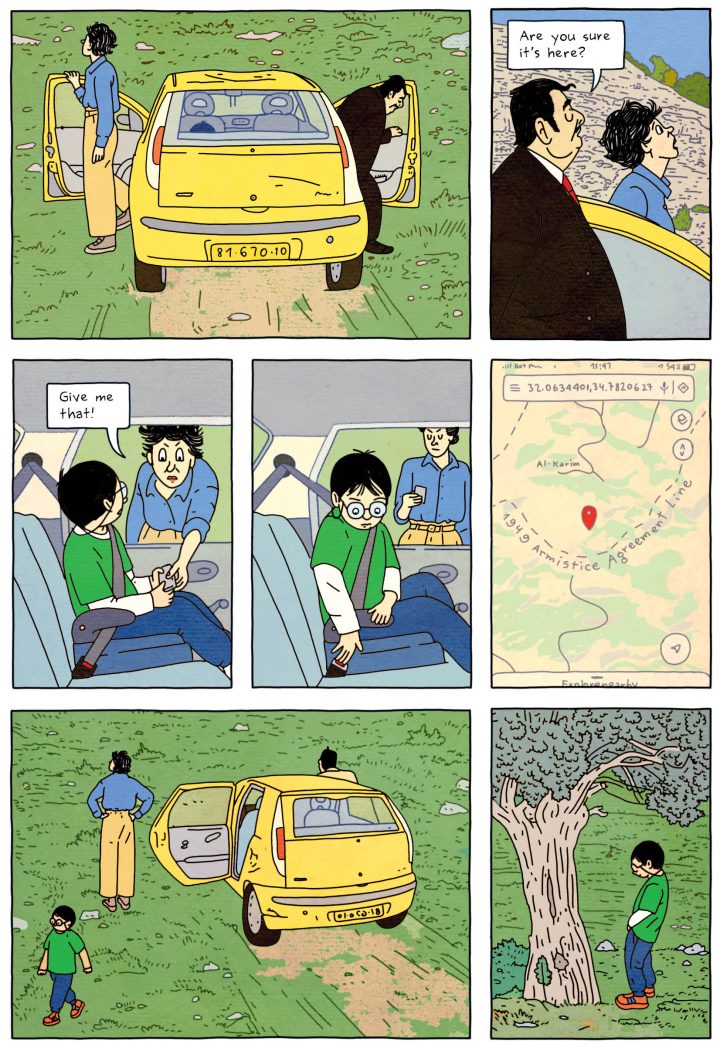

Tunnels is maybe a little messier in its drawings than her previous works, but that approach serves the story, as Nili (our protagonist) crashes through everything in her path like a juggernaut. Even more than usual in Modan’s books, every character here cares only about achieving their goals, regardless of who gets hurt. Nili wants to finish the archeological dig to find the Ark of the Covenant that her father started years ago, before his demotion from academia and the onset of his dementia, to preserve his legacy. Rafi, a rival archeologist, also wants to find the Ark, to cement his own legacy as the greatest in his field and to receive public recognition. Broshi, Nili’s brother, who works for Rafi even though Rafi stole credit for his father’s work, wants tenure and will betray his family to achieve it. Abuloff, who bankrolls Nili’s dig, wants to collect objects at all costs, especially because his wife is making him donate his existing collection. Doctor, Nili’s son, wants to play video games 24/7, fixated on the remaining percentage of battery life in this or that device, and is easily manipulable. Gedanken, recruited by Abuloff to provide diggers and a bulldozer, wants land for Israel and glory for the Jews. ISIS appears around the edges, fixated on its own goals of an Islamic state. And so on.

Every character, in other words, has tunnel vision, and the title of the book is as much focused on these metaphorical tunnels as on the literal ones that different parties dig to try to find the ark. Too many tunnels dug under the foundations of something weaken the ground and cause what's above (communal property) to collapse. It's a strong analogy that doesn't feel like one in the reading because all these characters are so flawed and fascinating and prickly. They’re predictable and unpredictable in equal parts, which makes them interesting to watch.

Also, Modan has always had a sense for story pacing, doling out plot twists like well-spaced beads on a string. The way she breadcrumbs the fact that there’s something more going on between Broshi and Mahdi (a Palestinian digging his own tunnel who knows Nili from childhood) is a thing of beauty, communicated entirely through body language. First they shake hands under Nili’s gaze as she smiles in delight at introducing them. Broshi raises his eyebrows and widens his eyes. Mahdi draws his own eyebrows down and stares at Broshi intensely. We know immediately that they're attracted to each other. A few pages later they share a moment alone in the tunnel, saying nothing and not touching but coming close enough to one another physically that our initial impression is confirmed. Modan does this through a combination of wide shots and extreme close-ups, framing the middles of their bodies in a panel that reminds of the feeling of perceiving the closeness of another human without actually making contact with them.

Her work is alive with sensation. When people kiss, we feel it in our gut. When they’re in peril, it doesn’t feel scripted. She writes, in an afterword, of the moment we find ourselves in now, in 2021 and 2022, about “a loss of agreement regarding reality” and that “it seems that the only object that can claim total honesty is fiction itself. The fictional story (as long as it is not disguised propaganda) a priori never claims to narrate the truth. Humbly, it confesses to being mere fantasy, told from the viewpoint of one limited, and patently not all-knowing, person.” Our sensory experiences are just such—completely true to us, completely limited to our own brains and bodies, and, at the same time, shareable with most other creatures on our planet. In conveying specific experience sensitively and accurately, Modan not only translates the big to the small, but she shines a light on the path back from the small to the big and, perhaps, a better way to be in the world.