Trubble Club #5 is the Sistine Chapel of jam comics. This twelve-page broadsheet is designed to look like a standard newspaper's Sunday comics section, and it took 28 artists two years to painstakingly create the internally consistent, extremely dark strips it contains. The Chicago comics collective in question consists of some heavy hitters as well as several lesser-known cartoonists, and no credits on individual strips are given to reflect who worked on what. Frankly, given the panel-to-panel changes in each jam strip, doing these kinds of credits might have been impossible. Still, careful attention allows the reader to detect the hand of especially distinctive artists, particularly their lettering.

For the record, Trubble Club consists of Nate Beaty, Grant Reynolds, Laura Park, Jeremy Tinder, Aaron Renier, Edie Fake, Rachel Niffenegger, Bernie McGovern, Lilli Carré, Corinne Mucha, Jeffrey Brown, Lucy Knisley, Becca Taylor, Jose Garibaldi, Joshua Cotter, Joe Tallarico, Onsmith, Lyra Hill, Sam Sharpe, and Carie Vinarsky. The guests for this issue included Ezra Clayton Daniels, Craig Thompson, Thorne Brandt, Erika Moen, Antoine Dode, and Alec Longstreth. It's easy to pick out Carré and Park in particular, but playing spot-the-artist isn't a game intended by the artists of this broadsheet, unlike it was in the famous Zap jam comics. The intent here is a wholesale subversion of the familiar comics page, using the tropes of familiar cartoons in the nastiest of ways.

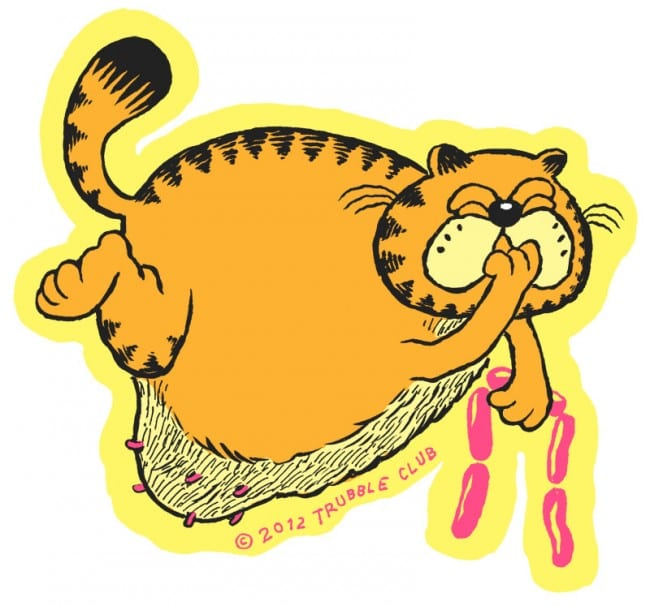

The strips here fall roughly into three categories: direct parodies featuring familiar characters, stylistic parodies that mimic the tropes of familiar strips, and strips that don't have a specific match but subvert the Sunday pages with violence, grossness, or sheer darkness. An example of the former is "Heathfield", a strip about a gigantic, floating orange cat which features J. Wellington Wimpy cutting the throat of Ziggy. The humor behind this kind of strip is pretty easy and obvious and not especially startling. An example of the second kind of strip is "Stretch Marks", a brutal parody of Baby Blues that features its mother character having a brain aneurysm and lying in a pool of her own blood, as she imagines getting a prize for a product called "Blood-bath-be-gone." From the dark set-up to the tremendous punchline, this strip really nails the spirit of this product.

Most of the strips that emphasize murder and mayhem are pretty straightforward, even as each jam artist tries to advance the narrative. "Lyle Carr, Model Train Conductor" features its train-enthusiast title character constantly blurting out "Chugga chugga chugga" as he murders women, only to meet his match in a woman who stabs him, whereupon a smaller version of himself pops out to menace her with an axe. It's a bit of silliness whose violence doesn't resonate, unlike "Misery Loves Stefanie" (about a masochistic goth kid with a crush on a sadistic teenager), "Methyl" (about a drug addict mom who does terrible things to her baby), "Peach Fuzz" (an adventure strip starring toddlers who have to battle a foe with SIDS vision and the dreaded Cradle Robber), and "The Horror, The Horror" (another adventure strip with a talking dog that features a penis-chomping zombie girl).

This is a taboo-smashing, envelope-pushing kind of comic, featuring pedophilia, murder, bestiality, gore, ritual sacrifice, and a poor boy whose pituitary and prostate glands are in opposite places (leading to "leaks" from his head), causing his vagina-foreheaded teacher to demand he stay after class. My two favorite strips in the book, however, offer differing takes on more modern strips. "Digi-Dad" is about a father who witnesses a brutal police attack, and reports what he's seen on Twitter, only to get accused of "douchebaggery" by a random internet asshole. After going to heaven, wherein he has access to the cosmic Google's safe-search and turns it off, he causes everyone on earth to get freaky (including at his own funeral), leading his son to tweet, "My dead dad is awesome." Still, the best and darkest strip in the book is "Joint Custody", a pastiche of continuity family strips like For Better Or For Worse. Drawn with no attempt at a punchline whatsoever, the strip follows a dad kicked out of his house by his wife (whose frowning dog is in total solidarity with her) and his visit with his two young children. The four-way split panel where the dad and the two kids are crying out exaggerated beads of sweat/tears and the mom & dog are expelling the same as tears of laughter is a devastating, awesomely funny image. I wish I knew who drew that one in particular (Onsmith?), because it's so effective. The final two panels consist simply of the brother (wearing too-tight Spider-Man pajamas) going to his sister's room at night and crying to her that he wishes mom and dad would get back together.

While not every strip is in that same category of dark, conceptually brilliant humor, every one is at least worth looking at. That's not something that's generally true of most jam projects, nor is it true of the wave of broadsheet comics that have been published over the last couple of years. Trubble Club #5 takes advantage of its format, acknowledging and parodying its past as a way of making the format part of its devastating, nasty and pitch-black sense of humor. As an anthology of like-minded artists, it's definitely one where the ego of the artist is subdued in favor of the overall project itself, which marks it as a unique sort of art object. Unlike most jam projects (which are usually quick-and-dirty excuses to publish something), this one obviously was important to its participants and that showed in the level of craft and care shown in every panel.