With The Strange Death of Alex Raymond, Dave Sim and Carson Grubaugh have delivered a book that is difficult to define, hard to completely enjoy, and challenging to recommend.

It is a masterpiece of sorts, but it’s also a bit of a mess.

Beginning as an offshoot of Sim’s experiment in photorealism, the comic book series glamourpuss, SDOAR uses Raymond’s death as the starting point for Sim's excessively obsessive exploration of “comic-art metaphysics.”

Sim uses this vague term throughout the book to explain away the seemingly endless array of strange coincides linking Raymond’s death to Gone with the Wind author Margaret Mitchell, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, Aleister Crowley, feminist dogma, Zelda Fitzgerald, romance comics from the 1950s, racism, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Al Capp’s brother, Big Ben Bolt, and many others.

What Sim is guilty of the most is promising too much at the beginning and reassuring the reader throughout that it will all make sense once he explains things. All will be revealed about the book’s main mystery—what are the real circumstances behind Raymond’s death?—if you just stick through to the final panel.

Sadly, that is not the case. The final chapter—or issue, since the conceit is that much of SDOAR is a collection of unpublished comic books—becomes a piling up of “evidence” meant to overwhelm the reader with the great secret Sim has found by gazing too deeply into Raymond’s perfectly rendered nightingale brush stokes. Rather than trying to convince the reader with his writing or art, Sim instead seeks to smother them under an avalanche.

By the end of the book, the reader comes away with the feeling of having climbed a mountain of bullshit in pursuit of fool’s gold. What had been promised at the beginning, what had been the driving force pushing you forward, turned out to have no real value at all.

Reading SDOAR is a frustrating experience.

And yet, there is beauty in this book.

Alex Raymond was killed on Sept. 6, 1956, when the car he was driving crashed into a tree in Westport, Connecticut. The 46-year old artist, who created the Flash Gordon, Secret Agent X-9, and Rip Kirby comic strips, was driving Stan Drake’s 1956 Corvette. Drake, the artist behind The Heart of Juliet Jones, was a passenger in the convertible at the time of the crash. Thrown clear, he survived with minor injuries.

This event serves as the apparent catalyst for SDOAR. It’s also a MacGuffin.

Like Charles Foster Kane’s sled, we’re never meant to get an explanation, despite Sim’s assurances. It’s a false lead and not the real subject of the book.

Dave Sim is.

The first half of the book hints at this with the artist’s lovingly rendered story of the early days of Raymond’s life and the development of photorealism. Though the art style has fallen out of favor these days, it inspired a generation of artists raised on Raymond’s work, from Drake and Al Williamson to Leonard Starr and Neal Adams.

Copying model images out of fashion magazines for glamourpuss, Sim begins to adopt and perfect Raymond’s techniques. Somewhere in the precise cross-hatching within a Rip Kirby panel, he begins to detect patterns and connections.

SDOAR is really about Sim’s obsessiveness.

Does art imitate reality or does art create reality?

With his “comic-art metaphysics,” Sim argues for the latter.

This is the root of his obsession about Raymond’s death. He sympathizes with the cartoonist’s outsider standing. In a photo of an awkward handshake between Raymond and Milton Caniff, Sim detects a glint of something critical in the eye of the creator of Terry and the Pirates.

Is there something there? Maybe. But probably not.

That’s what’s ultimately dissatisfying about reading SDOAR and makes it challenging to recommend. Sim wants us to sympathize with the creator’s struggle but does little to make us like him or care about his obsession. Like him and Grubaugh, the reader wants to just finish the damn thing.

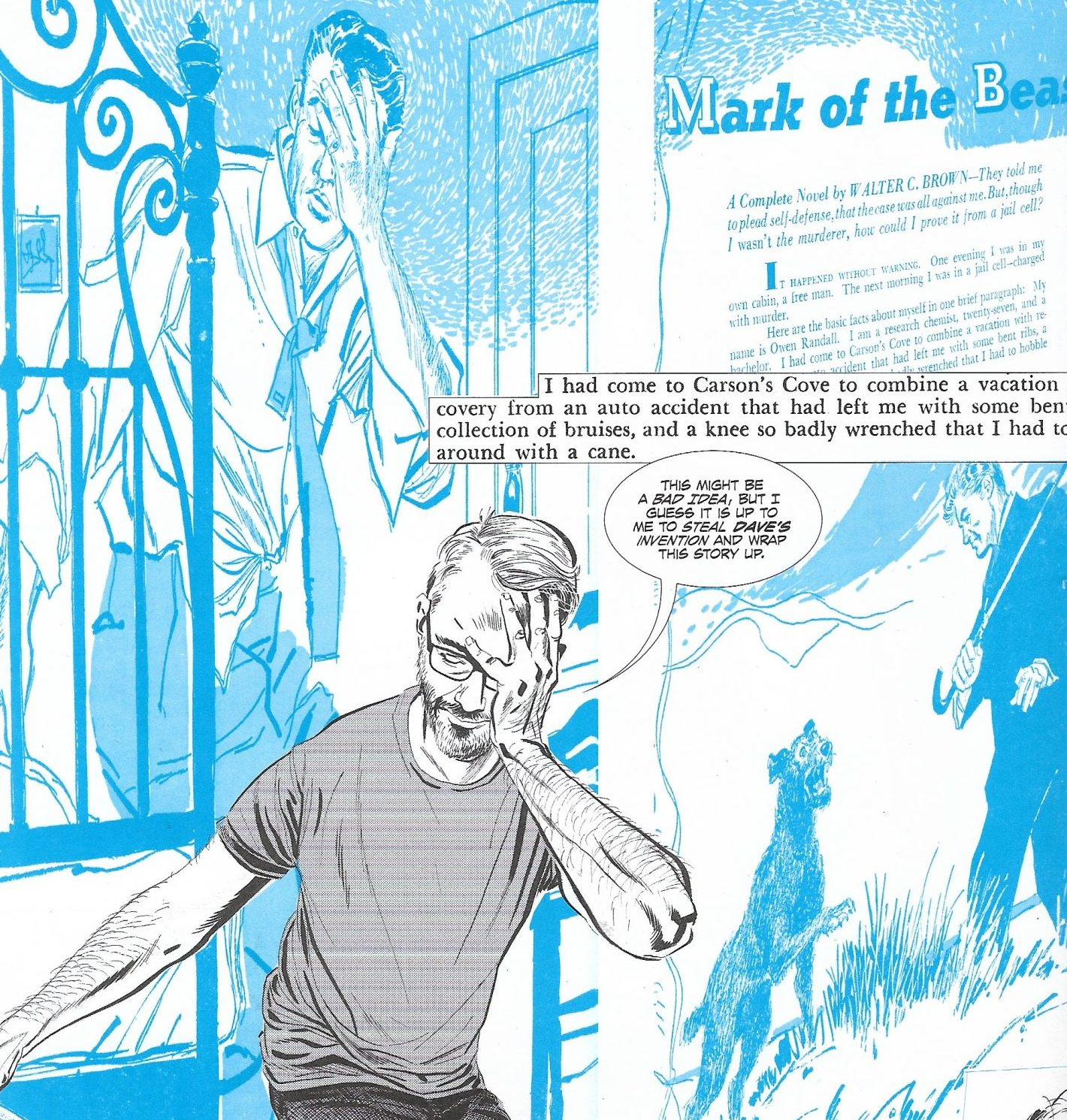

I said there was beauty in the book. The incorporation of other artists’ work and experimental use of layouts and typeface as storytelling devices are masterful through most of the book. But in the end, as Sim abandons structure for stream of consciousness, it all becomes rushed.

At several points throughout the book, Sim and other characters shout into the abyss, “DOESN'T ANYONE WANT THIS STORY TOLD!?!”

Ultimately, that lament appears to be the rationale for SDOAR’s publication. The book even reproduces a letter from Sim to a handful of Patreon supporters announcing the book will not be finished.

However, Grubaugh is shown in the final chapter (issue) heroically setting out to interpret Sim’s increasing bizarre and nearly incoherent ramblings, deciding that he will do his best to get the book over and done with so he—and we—can move on to other things.

He succeeds, and we’re left to question whether the effort was worth it.