Why celebrate Shirley Jackson? The question is an easy one, now—with the recent release of Ruth Franklin’s biography, A Rather Haunted Life—or any time. Jackson moved expertly between comedies of manners and tragedies of all sorts, writing short stories of great wit as well as novels of great dread. There is much to explore in The Haunting of Hill House, The Lottery and Other Stories, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and much to praise. But if the why of celebrating Shirley Jackson is easy, the how leads to more complicated questions, which Rob Kirby (a TCJ.com contributor) has navigated in compiling The Shirley Jackson Project.

Kirby’s tribute anthology was produced under one major constraint: Jackson’s estate holds the rights to her stories, precluding any straightforward adaptations. Many entries in the book are closer to meditations; the pieces will appeal most to existing converts, but they’re also evidence that these converts abound. Kirby, in his introduction, describes Jackson not as a horror writer—as she’s sometimes known—but as a writer interested in psychological states and psychological flux. This idea echoes throughout the anthology, especially in the autobiographical pieces (or comics that appear to be autobiographical). Several cartoonists use Jackson as a lens with which to examine fraught family dynamics and/or moments of instability in their younger years.

Eric Orner’s “Brendan in the Jungle,” possibly the best of these entries, documents a long-distance correspondence with a friend who’s beginning to self-destruct (and who’s reading a Shirley Jackson collection as he does so). Orner includes specific scenes from this collapse along with discrete, related images, while anchoring his panels with a tight grid and alternating white and gray backgrounds. On its surface, his story has less to do with Jackson than most pieces in the book, but in fewer than ten pages, “Brendan” manages to cover transitions, manners, and death—and if a reader reduced Jackson’s work to three elements, it might be these. Jon Macy’s “Words of Fire” is a more straightforward but still affecting piece about art and abuse, in which Macy frankly and economically shares details of Jackson’s life and his own. Annie Murphy’s “Afraid of Ghosts” and Ivan Velez, Jr.’s “Hill House Ain’t Got Nuthin’ On Me!,” two other comics in the micro-memoir vein, are less satisfying reads, at least within the (literal, spatial) confines of the format. Velez, Jr.’s panels appear forcefully cropped, and both pieces feature cramped lettering, too tiny for the book’s trim size.

Eric Orner’s “Brendan in the Jungle,” possibly the best of these entries, documents a long-distance correspondence with a friend who’s beginning to self-destruct (and who’s reading a Shirley Jackson collection as he does so). Orner includes specific scenes from this collapse along with discrete, related images, while anchoring his panels with a tight grid and alternating white and gray backgrounds. On its surface, his story has less to do with Jackson than most pieces in the book, but in fewer than ten pages, “Brendan” manages to cover transitions, manners, and death—and if a reader reduced Jackson’s work to three elements, it might be these. Jon Macy’s “Words of Fire” is a more straightforward but still affecting piece about art and abuse, in which Macy frankly and economically shares details of Jackson’s life and his own. Annie Murphy’s “Afraid of Ghosts” and Ivan Velez, Jr.’s “Hill House Ain’t Got Nuthin’ On Me!,” two other comics in the micro-memoir vein, are less satisfying reads, at least within the (literal, spatial) confines of the format. Velez, Jr.’s panels appear forcefully cropped, and both pieces feature cramped lettering, too tiny for the book’s trim size.

The anthology doesn’t lack for humor, which is important—few readers would dispute Jackson’s power to disturb, but her writing can be quite funny too. Gabrielle Gamboa contributes “Recipes for your Demise,” a brief and enjoyably mean-spirited set of illustrated, capsules-sized notes on the real, historical hazards of foods mentioned in Jackson’s stories. Asher and Lillie Craw also cover Shirley Jackson and food—and the collection probably did not need this done twice, all things considered—but the more memorable of their two entries concerns “the hidden world of the buildings” in Jackson’s work. This comic devotes each of its pages to a different location, and each page reads like a cheeky but earnest micro-essay. Not to be outdone, curator Kirby and artist Michael Fahy provide a two-page index of Shirley Jackson archetypes, with Fahy’s coarse-looking portraits, wrought of rough lines and spot blacks, complementing the wit with which Kirby links together various Jackson characters.

The anthology doesn’t lack for humor, which is important—few readers would dispute Jackson’s power to disturb, but her writing can be quite funny too. Gabrielle Gamboa contributes “Recipes for your Demise,” a brief and enjoyably mean-spirited set of illustrated, capsules-sized notes on the real, historical hazards of foods mentioned in Jackson’s stories. Asher and Lillie Craw also cover Shirley Jackson and food—and the collection probably did not need this done twice, all things considered—but the more memorable of their two entries concerns “the hidden world of the buildings” in Jackson’s work. This comic devotes each of its pages to a different location, and each page reads like a cheeky but earnest micro-essay. Not to be outdone, curator Kirby and artist Michael Fahy provide a two-page index of Shirley Jackson archetypes, with Fahy’s coarse-looking portraits, wrought of rough lines and spot blacks, complementing the wit with which Kirby links together various Jackson characters.

One sign of a good anthology is that even the misfires are interesting, and this is true of The Shirley Jackson Project. “Merricat” by W. Woods posits a series of found sketches by Merricat Blackwood, of We Have Always Lived in the Castle—sort of a losing endeavor by default, as the novel itself takes a deep dive into Merricat’s interiority, but it’s still fun to see the choices made sketch by sketch. Jennifer Camper’s “The Guest Bathroom” begins another losing game, putting a Jackson-like figure in the center of its story about a gradual home invasion, and also adopting a Jackson-like voice for its captions. In other words, it’s particularly easy to measure this piece against Jackson’s own work. But Camper still boasts one of the collection’s most dexterous plot-level feats, weaving together strands of the Jackson stories “Like Mother Used to Make,” “Trial By Combat,” and “The Villager” within one comic.

In an irony Jackson might have appreciated, two of the most evocative pieces here are nearly (in the case of Robert Triptow’s “The Haunting of Fernwood Drive”) or entirely (Maggie Umber’s “The Tooth”) wordless. Triptow renders his comic in lush pencil and sticks to a first-person point of view. Like a few of the other pieces in the anthology, this one involves the veiled threat of parental menace and a move toward self-liberation. And although the comic would stand out for the novelty of the perspective alone, Triptow’s curious combination of this POV and the absence of dialogue or an inner monologue from the person whose view the reader inhabits makes for a unique blend of airiness and discomfort.

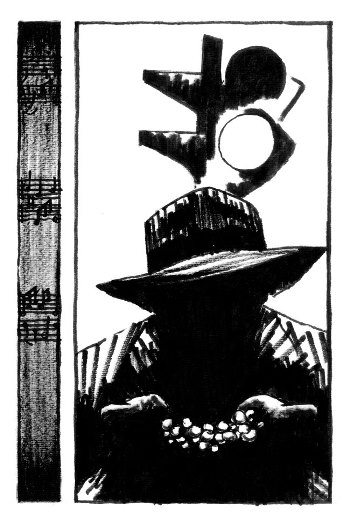

Umber’s “The Tooth” is presented as the centerpiece of the collection, or maybe it just asserts itself as such. Umber takes fragments of one of Jackson’s most hallucinatory stories and builds a visual tone poem from them. The comic isolates certain moments from Jackson’s original, about a woman traveling by night toward a dentist appointment, while maintaining the irresolute qualities of Jackson’s original. The blurred border between dreams and waking life, subjectivity and reality, is the substance of “The Tooth,” and Umber’s approach (brush pen on watercolor paper) serves this tension. Lines and objects lie on the page as if they will fade away if the reader’s gaze lingers—and lie by omission as well, each image sharing and concealing different parts of the story. Meanwhile, most consecutive panels fall far enough apart within the story’s timeline that performing closure becomes a bit like leaping across a series of widening puddles. Elusive but memorable, creepy but restrained, it’s a fine comic to anchor an anthology that honors Jackson by refusing to reduce her work to any one element.

Umber’s “The Tooth” is presented as the centerpiece of the collection, or maybe it just asserts itself as such. Umber takes fragments of one of Jackson’s most hallucinatory stories and builds a visual tone poem from them. The comic isolates certain moments from Jackson’s original, about a woman traveling by night toward a dentist appointment, while maintaining the irresolute qualities of Jackson’s original. The blurred border between dreams and waking life, subjectivity and reality, is the substance of “The Tooth,” and Umber’s approach (brush pen on watercolor paper) serves this tension. Lines and objects lie on the page as if they will fade away if the reader’s gaze lingers—and lie by omission as well, each image sharing and concealing different parts of the story. Meanwhile, most consecutive panels fall far enough apart within the story’s timeline that performing closure becomes a bit like leaping across a series of widening puddles. Elusive but memorable, creepy but restrained, it’s a fine comic to anchor an anthology that honors Jackson by refusing to reduce her work to any one element.