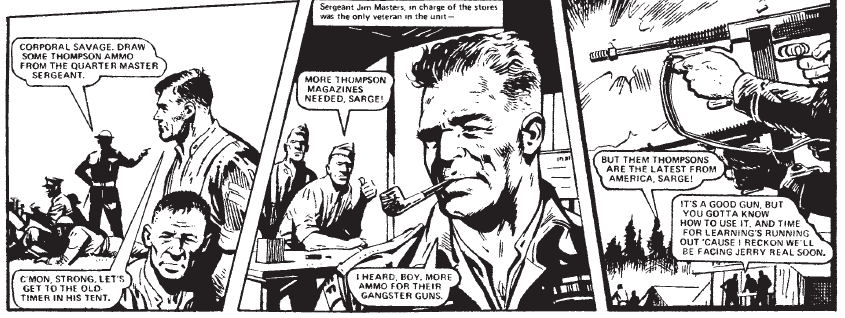

The first page of opening installment of The Sarge features four panels. Up top, a broad opening tableau is centered around a Vickers machine gun being fired directly at the reader by two typically presentable members of the British Expeditionary Force. Three lower panels depict a couple of lumpier, less well-turned-out looking soldiers enquiring after ammunition. An askew caption informs us that we’re in the dying days of the Phoney War, the eight-month long period of limited contact that took place between France and the United Kingdom’s declaration of war against Nazi Germany, following the invasion of Poland in September 1939, and the Battle of France the following May.

The soldiers at the front of the first panel are jubilant; they marvel at the unfettered killing power of their stationary water-cooled weapon, confident that–despite predating the First World War–this antiquated device will be more than capable of doing some damage, should their stay in France heat up. Artist Mike Western constructs this feature image with three parallel planes that neatly divide this British fighting force along class lines. Two of the upper (officer) class are at the forefront, getting their jollies by burning through an obscene amount of ammo. Just behind them are what looks like a drill sergeant, gazing into the middle-distance, and a grimacing hanger-on. Both men passively observe their ‘betters’, forming a tacit perimeter that bars any lower class oiks from trespassing. Perhaps they even hope that they will (eventually) be allowed to have a go themselves? At the back of the image, on the far right, are two disheveled-looking conscripts: disconnected and observing.

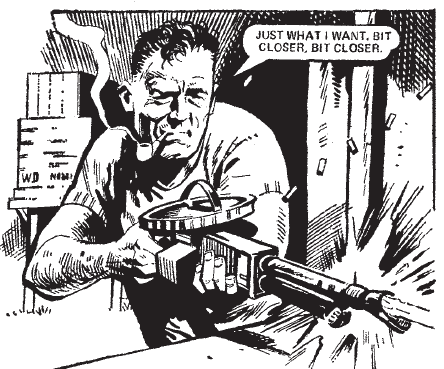

The panel that follows this opener makes it obvious that such scrutiny isn’t appreciated - the drill sergeant sends both conscripts away from the scene, tasking them with securing more bullets for further incidents of wastage. Western’s whole page layout thus instantly centers the typical heroes of British war fiction–the aristocracy–then quickly discards them, preferring to pursue a different point of view. The eponymous Sarge, Jim Masters, is introduced in the third panel. Although obviously older, Masters has a similarly broad build as the dismissed soldiers. He smokes a pipe, not unlike Popeye, and his face could be on loan from Hollywood hard man Burt Lancaster, as seen in John Frankenheimer’s 1964 film The Train. Masters, we are told, is the only veteran in the unit, lumbered with a menial role in the armaments hut. Rather than make the most of this human encyclopedia, someone–likely one of the gentlemen yukking it up in the opening panel–has made the decision that Masters is washed up, capable of no contribution more complicated than doling out stacked magazines to ‘lower born’ errand boys. Masters, in a brief, neatly-typed bubble, acknowledges the chronic misuse of precious resources going on around them, not just in terms of equipment stress but also in terms of operational organization. He intuits the impending German attack massing overleaf, flatly stating that everybody’s time would be better spent training with these weapons rather than a select few running them dry.

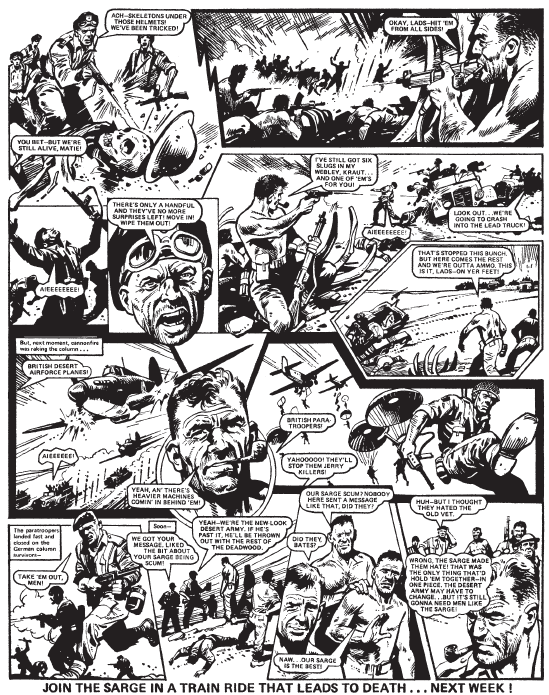

Of course, Masters is proven correct. The following morning German mechanized infantry comes crashing through the nearest forest and immediately guns down the officers who were so enamored with the Vickers. This spot of radical slaughter leaves a freshly-shaved Masters to rally the remains of his wide-eyed platoon.

The Sarge, the latest from Rebellion in their Treasury of British Comics range, is a series that originally ran in the war anthology Battle Picture Weekly from 1977. The magazine was pitched at preteen-and-up boys and ran from 1975 up until the late 1980s, when it was absorbed by a relaunched Eagle, the home of Dan Dare. Battle’s run ended not long after the comic lost the license to produce works related to Action Force - a spin-off of the Action Man doll line that was used to introduce the various G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero figures and playsets to the European toy market. Published by IPC Magazines, Battle was originally devised as a rival to DC Thompson’s Warlord, a war-themed comic that was attracting a sizable audience thanks to its action-packed take on the Second World War. IPC’s response was to contract ex-DC Thompson staff-turned-freelancers, including Pat Mills, John Wagner and the eventual writer of The Sarge, Gerry Finley-Day, to create an alternative. Quite unlike other boy’s war comics of the period (and, really, any period since), Battle was actually interested in the perspectives of soldiers who came from working-class backgrounds and died in the thousands on the battlefields of Europe.

Written by Finley-Day and drawn, primarily, by Western (Jim Watson fills in for Western on a couple of the installments collected here, while Mike Dorey inks three of Western's pages), The Sarge represents British war comics at a particular moment in the 1970s; one in which a great many of the strip’s readers would have had older family members who were directly touched by the conflicts that inspired these stories. If taken seriously, and not excessively glamorized, these comics could have offered their younger readers a kind of insight into the older, brutalized generations that were raising them - a paper and ink answer for the kind of queries that might otherwise invite painful introspection. The Sarge makes this idea of an immediate human record key to its central concept: a fatherly veteran of the First World War leads a group of young and dangerously inexperienced soldiers throughout the various European and African campaigns of the Second World War. Masters, then, is an idealized father figure; a man who can be both endlessly inventive in the art of warfare, while still fair and humane. Masters, the vehicle through which themes and ideas are communicated, is supernaturally empathetic: able to tune into the fears and anxieties of those he fights alongside. This Sergeant is not just capable of caring about his men as if they were his sons, his reach extends to the various would-be (often non-British) allies his platoon encounters. He offers all a therapeutic re-evaluation founded in violence - one ruthlessly directed at the common enemy of creeping fascism. The Sarge is romantic in this sense; it imagines a chain of command capable of both affection and an instructional, all-inclusive masculinity.

By the end of the 1970s, during its original print run, The Sarge would have appeared in Battle alongside work such as Alan Hebden’s & Eric Bradbury’s Crazy Keller, Western’s HMS Nightshade with writer John Wagner, and Charley’s War. Written by 2000 AD architect Pat Mills and illustrated by the incomparable Joe Colquhoun, Charley’s War was (unusually) a strip focused on the First World War, a conflict generally agreed to be lacking in the jingoistic valor required to power an ongoing story. Told from the perspective of an underaged and under-educated volunteer, Charley's War stands as Battle's most lauded and far-reaching serial - it should be the crown jewel of the Treasury of British Comics releases, but the comic swings in and out of availability in print. For instance, physical copies of the second volume of Rebellion's Definitive Collection, the book that compiles stories surrounding the still-controversial Étaples mutiny, are much harder to come by than the first and third volumes. Fortunately, all three releases are available digitally through the Treasury of British Comics website.

Where Charley’s War trades in suffocating doom with a blackly comic twist–the strip begins with Charley reaching a shell-battered front just weeks before the truly nightmarish Somme offensive–The Sarge is largely a series of beautifully-rendered action incidents. Mills’ and Colquhoun’s story takes in real horror: men drown in muck; messengers bleed out in bone-filled craters; teenagers are used as human shields by cowardly officers; and old men die delirious, convinced that the shell-shocked lads from their squad are their beloved but already departed sons. Charley’s War is the totality of an unjust and bloody war collapsing in on the individual.

Comparatively, although by no means whitewashed, The Sarge is built around brief, even fanciful instances of wicked human ingenuity - typically arising from Sergeant Masters’ quick-thinking. Finley-Day’s themes of assailed camaraderie within the confines of an unending trek anticipates the writer’s work on Rogue Trooper for 2000 AD in the 1980s. Masters’ interchangeable platoon, not unlike Rogue’s bio-chip comrades, are a Greek chorus that provides expository alarm and allure when considering their indefatigable hero. Like sports commentators, they decode and describe the lethal fluency to which they stand as witness. Western maintains an intense back-and-forth when considering battles - frothing close-ups of creased-up faces crowd against widescreen action detailing squads upon squads of Nazi soldiers being pumped full of lead. Grimy, grubby faces swim in and out of the action, screaming blood-curdling invective at their audience. Western’s panel layouts often defy a dutiful sense of neatness as well. They are exciting in and of themselves. More than once they present as shards of glass shattering across the page as if a bullet has just splintered a windshield. In-strip action interconnects and overlaps in such a way that the page’s events seem to be happening all at once.

The Sarge, then, taken as an anthology feature, is the brief, reassuring respite between heavier stories: an effect perhaps obscured by this collection. Episodes rarely run longer than three pages, often with a color introductory spread followed by one page of concluding black and white. By billeting all these installments together–many of which lack a narrative arc broader than a relentless trudge forward–The Sarge’s bite-sized mayhem takes on a stop-start quality, not attuned to longform reading. Yet when consumed in their original form, as one-shots, Finley-Day’s and Western’s work shines; an aperitif offering up the relentless, righteous extermination of Nazis as entertainment before readers turn the page and sink their teeth into the morally complicated material swirling elsewhere in their ten pence dreadful.