Glyn Dillon's return to comics after several years doing storyboards for movies and TV marks the first long-form comic he's ever written, and it's clearly a labor of love. It's a bit all over the place in an agreeable fashion. It's part character study, part romance comic, part disease comic, and part fantasy comic. At times, he shows great restraint in his storytelling and at other points he lays things on thick. What is consistent is page after page of loosely rendered, expressive, and beautifully colored art. His figure drawing is simply exquisite, and many pages of the story are carried by a simple arch of the eyebrow or nod of the head of the story's protagonist. His attention to body language, gesture, and the ways in which people interact with each other in space near Jaime Hernandez-levels of sophistication.

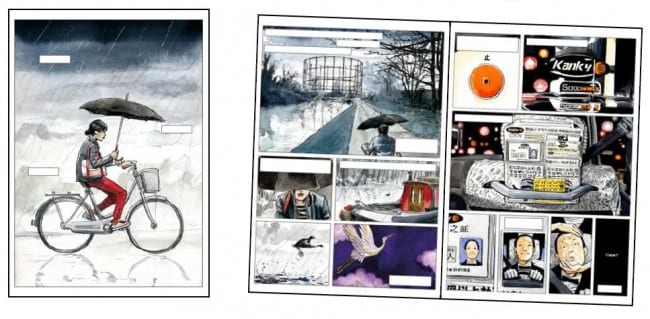

Nao Brown is a hafu (half-Japanese person) living in London, though she considers herself to be British thanks to her mother. She's an artist and designer with a closely-held secret: she suffers from obsessive-compulsive disorder/pure obsession. The way this condition manifests is different for each individual, but for Nao it comes in the form of intrusive, homicidal thoughts. OCD is closely linked with depression and feelings of worthlessness; in Nao's case, she tries to combat these feelings with her mantra of "Mum thinks I'm good," as well as reminding herself of the other people who don't think she is a horrible monster capable of murdering children. Dillon manifests these thoughts in jarring sequences where Nao actually appears to do something horrible (stab a pregnant woman, push someone in front of the train, smash someone's head into a wall), only to quickly shift back to reality. At the same time, there's a fantasy sequence involving a character created by Nao named Pictor, who must try to rescue his squabbling family after being turned half into a tree by a being called the Nothing. Dillon has described these sequences as a cross between Moebius and Miyazaki, and that's fairly apt. The intensity and vibrancy of detail of Moebius is there, along with the dark storytelling tendencies of Miyazaki.

The book follows Nao as she tries to live her life and find love. Dillon is wise not to spell out Nao's mental illness too explicitly at first, jarring the reader with her violent ideations and concomitant ranking ("7 out of 10", with a higher number being worse). The book is most interesting when Dillon follows her daily routine and her attempts to cope with her illness while sharing it with no one except her flatmate. At the same time, he's careful to make this a story about a set of characters with their own unique qualities and not just a set of symptoms. Dillon loves drawing rumpled characters of various shapes and sizes, all of whom are clearly dealing with their own issues (more on that in a moment). Nao's friend and employer Steve is a short, twitchy mess. Nao's crush and later boyfriend Gregory is a friendly bear of a man who's not quite aware of his size. The grizzled and worn man at Nao's Buddhist center has what she calls a "Shane McGowan smile," a jagged assembly of snaggleteeth. These are bodies that really occupy a space, and it's a genuine pleasure to see them interact.

It's no surprise that in a book about an illness as inherently self-absorbed as OCD that Nao would experience the fundamental attribution error. That is, she assumed that everyone's behavior and attitudes had something to do with her at all times, instead of realizing that everyone else had their own set of issues. She's incapable of seeing that Steve is in love with her and always has been, believing that he thought of her as a sister. She's unable to see that Gregory has deep-seated pain of his own that he's dealing with by using alcohol. While she tries various techniques to work on her issues (including "homework" that involves writing down her bad thoughts), she's too ashamed to actually discuss them. At the same time, she's charmingly odd in other ways, like disabling her flatmate's washing machine in order to get a repairman she has her eye on to come up and fix it and entice him into asking her out.

The main problem I have with the book is that when these problems come to a head, the way the plot unfolds winds up being fairly predictable. In a book filled with the anxiety that something bad might happen, it's inevitable that something bad will happen, if only to shake that feeling out into daylight. Something bad happens to Gregory after Nao has a huge freakout when she doesn't hear from him all day (resulting in her barely being able to keep it together), and they then have a huge fight where he calls her terrible. Telling someone who constantly thinks that they are evil and worthless that they're horrible is possibly the worst thing you can do to them, and her interior monologue spills out, demanding and then pleading that he say that she's not horrible, shouting out "10 out of 10!" over and over. Dillon then pulls out what I thought was a bit of a cheap shock and has something bad happen to Nao, and then fast-forwards several years into the future. The crisis she experiences, one that involves real physical pain, permanently alters the way she perceives the world and allows her to practice mindfulness without the constant, rushing distraction of her own thoughts.

While I appreciate that Dillon moves the characters to their final destinations without leaning on the easy sentiment of emotional moments of realization, it feels perhaps a bit pat and happy--almost too easy, in a way. Like the parallel fantasy story told in the book, there are rough times but a happy ending. What changed my mind about the ending and brought me around is the chilling final image of Nao's son, looking much like his mother in the first image of the book: a cool, funny photo of a confident-looking child. In Nao's case, she was really a twitchy mess in that photo (but was always good at hiding it), and the fear is that he may well wind up the same way. Dillon spells this out a bit too plainly, but it's a powerful image nonetheless. For the most part, Dillon is careful not to over-write in this book, letting his art tell most of the story, but he could have gone even further in that direction. While he lets Nao's OCD reveal itself to the reader, he does somewhat spill the beans on the first page when Nao tells the reader that she's "a fucking mental case." It's a tricky balance, especially for a first-time writer, but Dillon mostly manages to deftly juggle intensity, sincerity, humor and raw emotion.