Arrested Development

Adolescent male mass hysteria permeates Usamaru Furuya’s The Lychee Light Club. In some ways, this is an inversion of his adaptation of the 2002 J-horror film Suicide Club (titled Suicide Circle, the manga uses the film as a springboard, but Furuya was given free rein with his version). Suicide Circle also focuses on peer pressure and ritualized violence, but the teens in question are girls; prompted by a charismatic leader, they eventually turn their collective aggression inward, resulting in the film and the manga’s haunting central image: 54 smiling girls, hands clasped, leaping in front of a train. In The Lychee Light Club, brutality also (at first) bonds the group in question more tightly together: Zera, the megalomaniacal leader, obsessed with betrayal; fiercely loyal right-hand man Niko; effeminate Raizo; Peter Lorre-ish Kaneda; power-hungry Tamiya; the cutely disturbing Jacob; scientifically minded Dentaku (“Calculator”); perverted occultist Dafu; and bishounen Jaibo. The club creates a mechanical, fruit-fueled Frankenstein monster: Lychee.

A comparison of the clubs in Suicide Circle and The Lychee Light Club is instructive. The Suicide Circle meets on roofs; their symbol is sunlike, tattooed on their ears. The Lychee Light Club meet underground; their symbol is originally the kanji for light, when they’re just a light-hearted “secret” club of elementary school students who likes to play chess; but, as Zera’s influence grows and their purpose becomes more sinister, each individual becomes associated with a black chess piece, and Zera, specifically, by a black star. (So the ladies are “light” and the men “darkness.” Sorry, Sim.) Even their black school uniforms neatly lend themselves to Nazi drag (Zera, ever the eager wanna-be fascist dictator, addresses them in German.) In Suicide Circle, becoming sexually active changes the two main characters’ relationship and sets the stage for all that follows; in The Lychee Light Club, the 13-year-old boys are disgusted by aging and terrified of their impending puberty. Homosexual relationships are poisoned by jealously and power plays (more ero guro than yaoi) and the girls Lychee capture for the boys send them into a sexual panic. Both clubs violently resist growing up.

A comparison of the clubs in Suicide Circle and The Lychee Light Club is instructive. The Suicide Circle meets on roofs; their symbol is sunlike, tattooed on their ears. The Lychee Light Club meet underground; their symbol is originally the kanji for light, when they’re just a light-hearted “secret” club of elementary school students who likes to play chess; but, as Zera’s influence grows and their purpose becomes more sinister, each individual becomes associated with a black chess piece, and Zera, specifically, by a black star. (So the ladies are “light” and the men “darkness.” Sorry, Sim.) Even their black school uniforms neatly lend themselves to Nazi drag (Zera, ever the eager wanna-be fascist dictator, addresses them in German.) In Suicide Circle, becoming sexually active changes the two main characters’ relationship and sets the stage for all that follows; in The Lychee Light Club, the 13-year-old boys are disgusted by aging and terrified of their impending puberty. Homosexual relationships are poisoned by jealously and power plays (more ero guro than yaoi) and the girls Lychee capture for the boys send them into a sexual panic. Both clubs violently resist growing up.

The Lychee Light Club’s over-the-top gore, rape, sodomy, and dismemberment (graphically depicted) is contextualized by its framing device. The manga opens to a picture of a hand poking through a drape, followed by this title card: “Tokyo Grand Guignol now draws its curtain on its third show: Lychee Light Club.” (According to Mangaupdates.com, it’s an adaptation of a play.) Furuya’s oeuvre, grotesque and absurd, is informed by his training in Butoh dance; The Lychee Light Club not only draws on both of the aforementioned performance traditions but, with its metaphysical overtones, shares a little with the Theater of Cruelty as well. In the interview with his Garo editor Chikao Shiratori published in Short Cuts, Furuya explained that he had studied drama in college; this theatrical device distances the reader from the perturbing events to follow. Furuya also utilizes stylized, ornate drawing in The Lychee Light Club, darkening and intensifying the hatching and tones used in Short Cuts and Palepoli (his other works available in English, published by Viz), as befitting Lychee’s melodrama.

However, it is just this melodrama that undoes The Lychee Light Club. As they become more debauched, killing, kidnapping, and eventually turning on each other (prompted by Zera’s paranoia), Lychee becomes more human, learning about art and befriending Kanon, the beautiful Christian girl the club imprisons, worships, and eventually attempts to sacrifice. Though not out of place in a Grand Guignol, it is perhaps the insertion of a heavy-handed moral ending that throws it all off-kilter — Furuya’s work is often amoral, so the maudlin ending seems out of place in a work where people comment on the relative attractiveness of one another’s disemboweled intestines. (Actually, Niko and Zera are pretty funny at the end, but it’s too little, too late.)

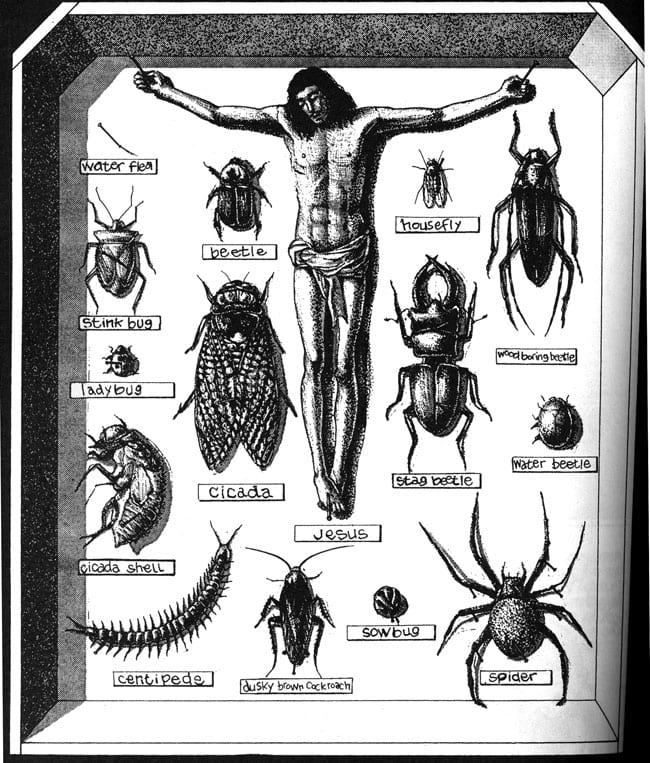

Even though it shares many of the same thematic concerns of his previous works — the fetishizing and idealization of youth and teen girls in particular (in which he is implicated); an obsession with crucifixion imagery, messianic figures, the profane, and suffering as a path to greater spirituality; how young adults, when faced with ineffectual or weak authority figures, will submit to the law of their peers, Lord of the Flies-style — The Lychee Light Club is unleavened by the characters’ goofy cheerfulness in the face of atrocity (something that occurs in some of Furuya’s previous works, and another distancing technique). Essentially, Furuya has a great, sick sense of humor; without it, this manga would just be sick, and in and of itself that’s kind of dull. He draws girls in a more clean-line style than boys, but focusing on the male rather than the female makes The Lychee Light Club a darker, heavier book — even just visually. (Though at times it is exquisitely drawn, such as in the climatic Chapter 8, “The Rose Execution”). Given his background in sculpture and dance, Furuya’s characters have always had somewhat exaggerated gestures; coupled with The Lychee Light Club’s feverishness, they come across as histrionic.

According to the promotional copy, The Lychee Light Club is Furuya’s breakthrough work (not, necessarily, his best), leading him to garner projects such as No Longer Human, his manga adaptation of the second-best-selling novel in Japan (forthcoming from Vertical). I’m curious to see what he does with a male protagonist who ages into adulthood. I’m hoping his entire backlist will eventually be available in the U.S. — other than the works I mentioned, Viz published one of his Teen+ titles, Genkaku Picasso. (I worked from a French edition of Suicide Circle.) However, though clearly a cartoonist has every right to go in whatever direction he or she wishes, creatively and/or commercially, I’m selfishly concerned that the further Furuya gets from his more self-expressive works, the harder it will be for me to respond to his cartooning. I count Furuya among the cartoonists that can disturb me and make me laugh at the same time; that number is so small, I would hate to lose one.

According to the promotional copy, The Lychee Light Club is Furuya’s breakthrough work (not, necessarily, his best), leading him to garner projects such as No Longer Human, his manga adaptation of the second-best-selling novel in Japan (forthcoming from Vertical). I’m curious to see what he does with a male protagonist who ages into adulthood. I’m hoping his entire backlist will eventually be available in the U.S. — other than the works I mentioned, Viz published one of his Teen+ titles, Genkaku Picasso. (I worked from a French edition of Suicide Circle.) However, though clearly a cartoonist has every right to go in whatever direction he or she wishes, creatively and/or commercially, I’m selfishly concerned that the further Furuya gets from his more self-expressive works, the harder it will be for me to respond to his cartooning. I count Furuya among the cartoonists that can disturb me and make me laugh at the same time; that number is so small, I would hate to lose one.