Here is a great truth about our age of gender fluidity, queer visibility, and increasingly ductile sexual identities: regardless of our sexual self-identification, we are all the same. An observation so banal as to be ridiculous, perhaps, but considered not as a platitude, but as a reminder of the universality of the human heart’s interior, it can be seen as both a threat and a salvation. We may not all experience emotions in the same context or conditions, but we tend to express them in identical ways; this is what makes art that is built around our difficulties in articulating the realities of our love and desire both universally resonant at its best and frighteningly banal at its worst.

There’s a little bit of both in The Lie and How We Told It, a gorgeous new graphic novel from Australian comics artist Tommi Parrish. It’s a simple narrative without much flourish: Cleary and Tim are old school friends who have been out of touch for a number of years. After a chance meeting in a grocery store, they have a night out to catch up (though neither of them are exactly keen to do so), and through the course of their conversations, they encourage one another, and themselves, to face up to some facts about their emotional states and relationship choices. It’s not much more than that, though it tries to be; it clearly wants to be something about the Way We Live Now, and on occasion it succeeds. There are moments of honesty and deceit that are telling in the way the two young people dart and slide around the truth of what they’re saying to each other. But there is a razor’s breadth between an author showing us characters who have trouble communicating and a text failing to communicate with the reader, and The Lie doesn’t always land on the right side of that distance.

The Lie and How We Told It draws its name from a song by Yo La Tengo, and the comparisons kept nagging at me while reading the book: with that particular band, you were always taking a chance whether, in performance, you would get them at the height of their expressive powers or a night of feedback-drenched noise that was only enjoyable to them. This was especially pronounced by the 2000s, when they settled into a comfortable haze of soundtrack albums and cover songs, some of them made for the film genre suitably known as mumblecore. For those who don’t remember that particular eructation of American cinema, it mostly revolved around middle-class white people who had a very difficult time making their feelings known to one another, to the detriment of everyone else around them. Despite it being a decidedly acquired taste, the genre has been oddly persistent and has lately turned up in quantity on second-tier television networks. Reading through The Lie, it’s almost impossible not to notice its deeply 2000s-ish feel, and while it dresses up its relationships in the complexities of a genderqueer woman and a man in deep denial about his own conflicted sexuality, it’s still that same old story of people who spend all their time not being able to say what’s on their minds.

The Lie and How We Told It draws its name from a song by Yo La Tengo, and the comparisons kept nagging at me while reading the book: with that particular band, you were always taking a chance whether, in performance, you would get them at the height of their expressive powers or a night of feedback-drenched noise that was only enjoyable to them. This was especially pronounced by the 2000s, when they settled into a comfortable haze of soundtrack albums and cover songs, some of them made for the film genre suitably known as mumblecore. For those who don’t remember that particular eructation of American cinema, it mostly revolved around middle-class white people who had a very difficult time making their feelings known to one another, to the detriment of everyone else around them. Despite it being a decidedly acquired taste, the genre has been oddly persistent and has lately turned up in quantity on second-tier television networks. Reading through The Lie, it’s almost impossible not to notice its deeply 2000s-ish feel, and while it dresses up its relationships in the complexities of a genderqueer woman and a man in deep denial about his own conflicted sexuality, it’s still that same old story of people who spend all their time not being able to say what’s on their minds.

Still, there’s a reason we still talk about this stuff. Yo La Tengo, for all their self-indulgence, can still put a bullet between your ears when they’re on their game. The mumblecore directors could sometimes coax a brilliant performance or a surprising observation about human nature out of their claptrap semi-realism. And The Lie and How We Told It, as much as it is satisfied leaving us in the company of two people who barely know themselves, does so with an aesthetic brilliance that commands our attention in a way its characters cannot. It’s one of the most strikingly executed books I’ve seen in years, and Parrish’s talents are impossible to ignore. It’s pretty annoying that we still have to remind people that comics are a visual medium, but here, the distinction is as vital as it is needed. Wherever there is weakness or uncertainty in the text, it is bolstered by beauty and boldness in the art, and the result is a book that reads better than it’s written.

Still, there’s a reason we still talk about this stuff. Yo La Tengo, for all their self-indulgence, can still put a bullet between your ears when they’re on their game. The mumblecore directors could sometimes coax a brilliant performance or a surprising observation about human nature out of their claptrap semi-realism. And The Lie and How We Told It, as much as it is satisfied leaving us in the company of two people who barely know themselves, does so with an aesthetic brilliance that commands our attention in a way its characters cannot. It’s one of the most strikingly executed books I’ve seen in years, and Parrish’s talents are impossible to ignore. It’s pretty annoying that we still have to remind people that comics are a visual medium, but here, the distinction is as vital as it is needed. Wherever there is weakness or uncertainty in the text, it is bolstered by beauty and boldness in the art, and the result is a book that reads better than it’s written.

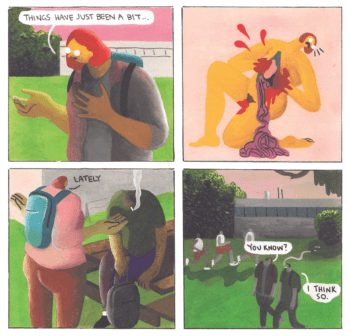

Parrish uses two distinct and complementary styles here. Their normal mode is a colorful painted look that’s halfway between graffiti and street art; in its dimensions, perspective, and use of color, it’s highly reminiscent of the work of Fernando Botero. The small heads, oversized bodies, and large, expressive hands create a sense of emotional depth and physical movement that drives the story along when the dialogue starts to flag. The use of painted color is absolutely lovely, especially in indoor scenes where the characters are backgrounded into their surroundings, as if they are becoming part of a mural we read as it goes. Even more effective is the second style, a finely drawn and precisely delineated ink drawing approach that is every bit as stark and intense as Parrish’s paintwork is loose and inviting. This style appears in One Step Inside Doesn’t Mean You Understand, a book-within-the-book by one “Blumf McQueen” that Cleary finds in a bush. It tells its own story of desire curdling into contempt and emotion robbed of expression that both mirrors and exacerbates the main narrative, and the choice to illustrate it in this way is Parrish’s surest and most confident move. It throws their entire dynamic into relief in a way the story itself could not hope to do.

Parrish uses two distinct and complementary styles here. Their normal mode is a colorful painted look that’s halfway between graffiti and street art; in its dimensions, perspective, and use of color, it’s highly reminiscent of the work of Fernando Botero. The small heads, oversized bodies, and large, expressive hands create a sense of emotional depth and physical movement that drives the story along when the dialogue starts to flag. The use of painted color is absolutely lovely, especially in indoor scenes where the characters are backgrounded into their surroundings, as if they are becoming part of a mural we read as it goes. Even more effective is the second style, a finely drawn and precisely delineated ink drawing approach that is every bit as stark and intense as Parrish’s paintwork is loose and inviting. This style appears in One Step Inside Doesn’t Mean You Understand, a book-within-the-book by one “Blumf McQueen” that Cleary finds in a bush. It tells its own story of desire curdling into contempt and emotion robbed of expression that both mirrors and exacerbates the main narrative, and the choice to illustrate it in this way is Parrish’s surest and most confident move. It throws their entire dynamic into relief in a way the story itself could not hope to do.

One Step Inside is, according to its introduction, “dedicated to pure, unconditional, everlasting love”, an irony sharper than the rest of the book is allowed to express. The choice to break the book into sections in this way it its salvation; if it were simply one or the other, it would be entirely different and far less successful. The tedium and shapelessness of The Lie and How We Told It would be too much to take on its own, and the severity and bluntness of One Step Inside Doesn’t Mean You Understand would probably be too difficult to sustain in a full-length work. But Parrish’s skillful offsetting of the two is what proves the book’s salvation and establishes them as a talent to remember. “These things are always funny until they’re not,” says the nameless protagonist of One Step Inside; the same can be said for tragedy, and that’s what the book is about. Our lives are always tragic except when they aren’t, and the story’s final panel proves that it’s a circular lesson that can and will repeated throughout infinite lives, as universal and ordinary as love itself.

One Step Inside is, according to its introduction, “dedicated to pure, unconditional, everlasting love”, an irony sharper than the rest of the book is allowed to express. The choice to break the book into sections in this way it its salvation; if it were simply one or the other, it would be entirely different and far less successful. The tedium and shapelessness of The Lie and How We Told It would be too much to take on its own, and the severity and bluntness of One Step Inside Doesn’t Mean You Understand would probably be too difficult to sustain in a full-length work. But Parrish’s skillful offsetting of the two is what proves the book’s salvation and establishes them as a talent to remember. “These things are always funny until they’re not,” says the nameless protagonist of One Step Inside; the same can be said for tragedy, and that’s what the book is about. Our lives are always tragic except when they aren’t, and the story’s final panel proves that it’s a circular lesson that can and will repeated throughout infinite lives, as universal and ordinary as love itself.