The Late Child and Other Animals is simultaneously Marguerite Van Cook's biography of her mother and her own autobiography, detailing five crucial turning points in both their lives. Written and expressively colored by Van Cook and illustrated by her husband James Romberger, these turning points are captured as a series of five poetic but emotionally restrained vignettes. That restraint was certainly a learned behavior, given that for her mother and herself showing emotion and breaking down was a sign not just of weakness, but the very difference between life and death.

In many respects, the book acts as a release, dedicated to examining, getting lost in, and ultimately unraveling secrets, both her own and her mother's. This exposure is a means of celebrating and acknowledging life, growth, and sheer survival. Doing so also sheds the harsh light of truth on shame, an ugliness which festers in secrecy and whispers. As Van Cook details, shame was far more than an abstract concept growing up; it meant the difference between her mother being able to keep her or giving her up for adoption.

Van Cook's colors are remarkably vivid, playing on the ways in which a child's recollection of their life is experienced as larger than life, but also somehow magical and fragile, like the images in the impressionist paintings she favored as a child. In the city, in the countryside and with the family of her best friend in France, she encountered a variety of wonders and amassed powerful memories. In each scenario, however, the vividness of life had a dark underbelly, and Romberger and Van Cook created a striking series of drawings to hammer that point home.

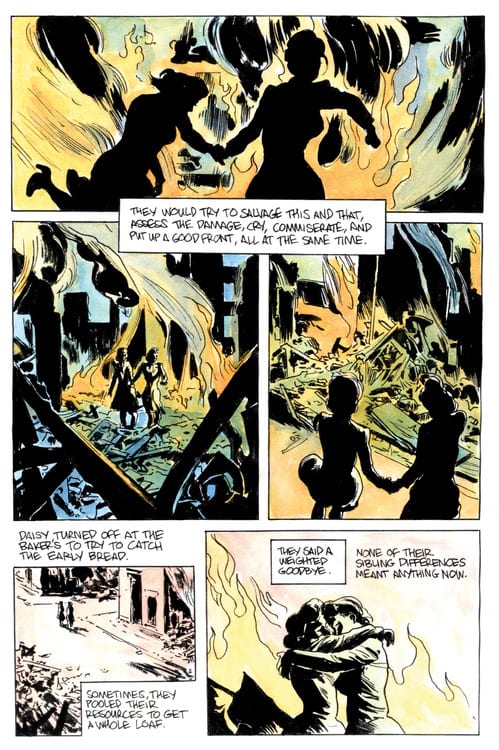

The first two chapters are devoted to two key events in the life of her mother, Hetty. Both revolve around shames that were unfortunately and humiliatingly public. The book opens with Hetty and her sister trying to survive the bombings in England during World War II, where the next raid could mean the death of your family or the destruction of your own home. There's one terrifying sequence where a bomb literally drops through her roof, and she simply and quickly picks it up and tosses it out the window, where it explodes in her garden, sending glass shattering everywhere. It's depicted in the most matter-of-fact fashion, with the only real future acknowledgment of it being the bed stand glittering from the tiny shards of glass still embedded in it.

Against this backdrop, Hetty hopes against hope that her beloved husband will return home soon from the war, especially since they had discussed adopting a child. She adopted a girl while waiting for him, but when her husband dies in an accident off in the desert, her world crashes around her--especially when the state wants to take the girl away from her since she was now a single mother. She wins that battle, at the cost of a great deal of stress and struggle. The second chapter is an account of the formal government inquest regarding Hetty having a child out of wedlock and determining if she should be allowed to keep her. Her mother had an affair with a man bivouaced in her house during the war. The council is uninterested in the human reasons why she would have an affair with a man she knew was married with children, because to speak of the ways in which war creates desperation simply would not do in that stiff-upper-lip culture. The scene is frequently terrifying, as Van Cook imagines the inquisitors as crows ready to devour her mother as though she is a juicy worm. Romberger is at his best in depicting the horror of the situation, though once again Hetty manages to triumph and keep her baby Marguerite.

The third chapter is the first from Van Cook's point of view, as a young child in the countryside. Initially a bright, pastoral interlude, this section turns dark when Van Cook gets lost in the thickets and tall grass, with her skin getting cut up and the sun beating down on her with no one to rescue her. She sees it as a lesson from nature showing her its full truth: beautiful but frightening, full of promise and adventure but also merciless and unforgiving.

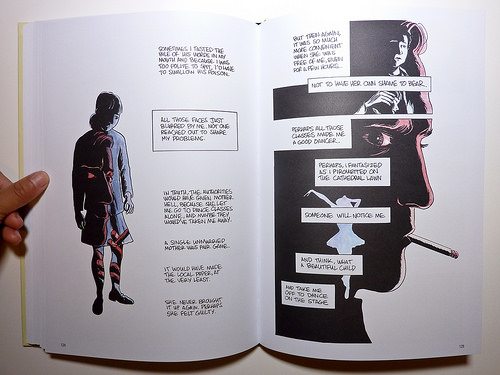

The fourth chapter is suspenseful and harrowing, as Van Cook describes her life in the city, playing with her best friend and attending a dance class. Then she introduces a murderous child molester and tells the story from his point of view, imagining the mind and experiences of the man who nearly took her own life. The man watches her class every day and notices that young Van Cook goes off on her own, giving him the opportunity to first try to cajole her and then spook her with sexually explicit language as he walks along with her. It's a steely-eyed but never detached account of the danger surrounding this incident, fitting for the daughter of a World War II survivor. What's most disturbing about it in some ways is that after she escapes (mercifully, before any physical harm was done), no adult stops to help her despite her screams. Even her mother can't afford to raise too big a stink about it, given her past and the appearances of allowing her daughter to take a bus alone at night. Once again, Romberger's images are up to the task of illustrating the tension and fear, with a memorable drawing of the man in silhouette with Van Cook's face appearing inside being especially bracing.

The final chapter is given over to Van Cook as a young teen, making a secret crossing between childhood and adulthood during a summer spent with her best friend's family in a French cottage. Three things in particular stood out in this chapter. First is the account of her first kiss with a boy at the beach: the perfect summer romance. Second is a lengthy description of a magnificent Sunday evening feast, with course after course being brought out. Last is the casual cruelty of her friend's mother, who is annoyingly strict and forces Van Cook to witness her pet rabbit be slaughtered and then served to her. Van Cook once again learns how to wall off that sort of cruelty, not giving her an emotional reaction at the dinner table.

While the book is all about exposing secrets, that last chapter demonstrates above all else that it's also about seizing a voice, especially as a woman in a relentlessly sexist society. Van Cook shows how she seized a voice for herself and in the process gave a voice to her mother. In The Late Child, Van Cook says things that needed to be said about her past, things that needed to be said for a long time.