THE BEST WAY TO DESCRIBE this monumental contribution to the history of comics is to quote from inside the dust jacket, to wit—: “The Goat Getters is an arresting narrative of the origin of the comic strip told from a new perspective by one of the leading cartoon storytellers of our time. It features a wild bunch of early Twentieth Century cartoonists based on the West Coast, including Jimmy Swinnerton, Tad Dorgan, George Herriman, and Rube Goldberg, whose domain was the sports pages. There they fashioned a bold, tough style, invented their own goofy slang that enriched the popular lexicon (to which the title of the book refers), and created characters such as Silk Hat Harry and the indomitable Krazy Kat.

“This exhaustively researched book is also an account, shown through original newspaper cartoons of the era, of the subjects of those cartoons. These include the landmark 1910 boxing match in Reno, Nevada between Jim Jeffries, the ‘Great White Hope,’ and Jack Johnson, the first African-American world heavyweight champion; the nationwide race riots that followed; the San Francisco graft trials that culminated in the shooting of the federal attorney prosecuting the case; and the trial of Harry Thaw for the murder of architect Stanford White, a crime of passion that centered on Thaw’s wife, showgirl Evelyn Nesbitt Thaw, whose beauty was celebrated by cartoonist Nell Brinkley.

“Campbell shows how these early cartoons developed the kind of dynamic anatomy and adult-oriented subjects that continue to influence comics and graphic novels today.”

Campbell, a Scot cartoonist now living in Australia, has produced a series of graphic novel-style works, beginning with the multi-part Bacchus in 1995 and including the autobiographical Alec and From Hell (the latter, an examination of the Jack the Ripper myth, written by Alan Moore), and many others.

Campbell has entertained for some years the notion that the American newspaper comic strip has its genesis on the sports pages of San Francisco newspapers, and in this volume, he successfully elaborates on the theory.

There’s little new in the basic idea: we’ve known for decades that Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff, ostensibly the first newspaper daily comic strip, started on the sports pages of the San Francisco Chronicle before Fisher was hijacked a few weeks later by William Randolph Hearst to continue the strip at the Examiner. And Fisher set the pace for a host of other cartoonists, many of whom were sports cartoonists, who followed with “strips” of their cartoons that ran across pages rather than down them.

But Campbell puts flesh on these bare bones with this lavishly illustrated tome, which makes a more-than-convincing case for his theory: every page carries at least one sports cartoon or, later in the book, comic strip. We learn more about the early years of cartooning at Campbell’s hands than we have learned anywhere else. I haven’t read the whole book yet, but I’ve browsed and read enough to realize what a treasure Campbell has produced.

THE BOOK IS METICULOUSLY RESEARCHED and scrupulously referenced throughout in captions and footnotes. An impressive achievement. In his final edit, Campbell was clearly working from page proofs: he alludes to other aspects of his subject by quoting page numbers fore and aft.

His purpose, Campbell says, is to show “how and why” the sports page was the logical place for comic strips to begin “and, more specifically, why San Francisco was the place it had to happen.”

Not being an American, Campbell sees things that have long evaded our attention. And that’s invaluable in an enterprise such as this. But he also sees things that aren’t worth seeing. Goat getters, for instance.

Campbell explains the book’s title: “To get a person’s goat, meaning to aggravate and upset them, originated in the custom of keeping a goat in a racehorse’s stable to calm the horse.” Unscrupulous personages, aiming to affect adversely the horse’s performance, would steal the goat and “thus unsettle the horse in order to gain a betting advantage in the next day’s race.”

The phrase, Campbell says, was coined on the sports pages where it was a fad for a few years until it eventually entered common parlance. All that is true, but I don’t think “getting someone’s goat” is as common an expression as Campbell thinks it is. Not common enough, say, so that cartoonists can be described as “goat getters”—although that is what some cartoonists assuredly do. They get the goats of those they satirize thereby unsettling them.

During the years of the popularity of the phrase, numerous drawings of cartoony goats adorned newspaper sports sections. A comic strip by the Chicago Tribune’s Sidney Smith evolved out of the practice: Old Doc Yak was a goat, and when Smith launched his more famous strip, The Gumps, it took Old Doc Yak’s place in the Trib.

Campbell scatters miniature goats in the margins of the book through the last half. But I still wonder at the assumption he made about the popularity of the phrase when he employed it in the title of the book.

So obscure are some of the gems of history unearthed herein that we can scarcely be certain of their authenticity. Campbell makes one debatable “mistake” that I know of. He says Bud Fisher copyrighted his strip A. Mutt on the first day it ran in Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner; but Fisher himself says he jotted “Copyright 1907 by H.C. Fisher” in the corner of the last panel of the last strip he did for the Chronicle.

Fisher had consulted a copyright lawyer, who told him he should make the copyright declaration on three printed strips, but Mutt had only that last day to run in the Chronicle. So Fisher also jotted the same message on the first two of his strips to run in the Examiner, making the requisite three notifications.

Obviously, Campbell is close enough, and if he’s that close on everything (and on most, he’s undoubtedly right on the money), we’ve got a magisterial history here.

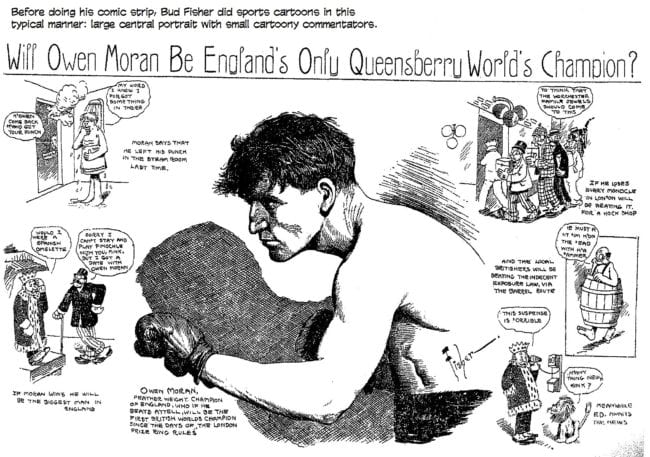

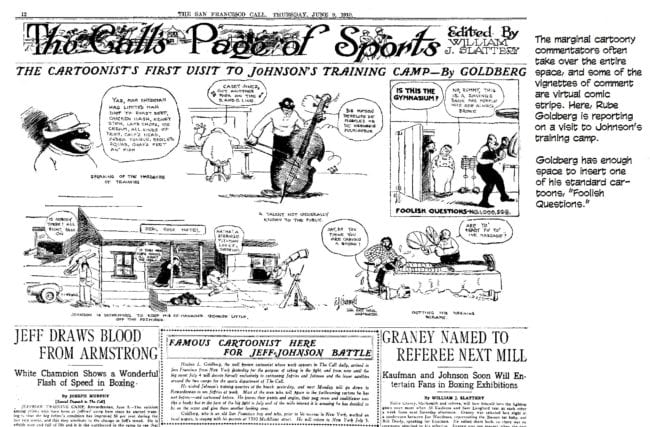

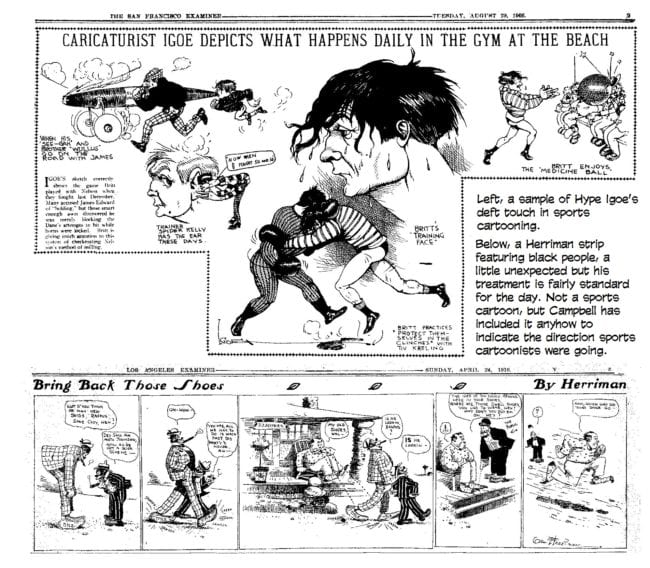

I'M NOT SURE WHY San Francisco was the only place sports cartoons could evolve into comic strips. But the evolution is undeniable: sports cartoons frequently—almost by definition—included a large picture, usually a realistic portrait of the athlete that was the subject, surrounded by smaller cartoony pictures (famed sports cartoonist Willard Mullin called them “goomies”) that expanded upon the subject. The comic strip, Campbell demonstrates, “grew out of this marginal byplay” taking place in the sports cartoon. He has assembled an impressive array of persuasive evidence.

Sometimes when the sporting news of the day included only an impending event and not a famous athlete, a sports cartoonist would do a series of “goomies” commenting on the coming event. And the goomies often appeared in a horizonal strip across the top of the page.

We’ve known that Mutt’s betting on horse races was the original purpose of Fisher’s strip, which ran in the sports section, betting on horses being a sport. And Billy DeBeck’s Barney Google originated as a way for sports cartoonist DeBeck to comment on an upcoming prize fight.

Even in my haphazard browsing, I discovered gems of comics history that I had never uncovered. For years, I’d run across the name Hype Igoe in connection with Tad. But I knew nothing about Igoe, and found no references elsewhere. Campbell shows us some of Igoe’s cartoons and explains his name: it was given to him by an elevator operator in Igoe’s newspaper’s building who thought Igoe was so skinny he looked like a hypodermic needle.

:

WHEN NELL BRINKLEY, FRESH IN NEW YORK from a little town in Colorado (Edgewater, my home town), started covering the famous “trial of the century” of Harry Thaw, gaining instant fame with her frilly portraits of the “wronged woman,” Evelyn Nesbitt, she did a short elegant pictorial biography by way of introducing herself to the paper’s readers. Tad, also on the paper (Hearst’s Evening Journal), mimicked her treatment with a visual biography of his own. And he did encores on other topics for several days following, every time a Brinkley picture appeared in the paper. He also mocked the Journal’s daily breathless coverage of the trial by putting his pet dog in the docket.

Mutt and Jeff wasn’t six months old (and Jeff hadn't yet showed up) when Bud Fisher borrowed Tad’s device, making a local court case his centerpiece. He plunged Mutt into a trial for stealing money to support his wagering compulsion. The trial quickly degenerated into farce, ridiculing various court officials, and I’ve always wondered what local events it must have been referring to.

Turns out, Fisher was mocking a notorious trial currently taking place in San Francisco about municipal graft. Campbell decodes some of the satire by giving us the names of some of the persons Fisher was mocking: lawyer Beany in the strip was a stand-in for federal prosecutor Francis J. Heney, who had been imported for the task of taking down the grafters. (He was shot for his trouble but recovered.)

The leading crusader against the graft was Fremont Older, editor of San Franciso’s Bulletin, but he never appeared in Fisher’s strip. According to his biographer Evelyn Wells in Fremont Older (1936), the fiery editor wanted to take down San Francisco’s corrupt mayor, Eugene Schmitz, and the brains behind the major, boss Abe Ruef. Older succeeded, but, afterwards, began to feel bad about Ruef. Suddenly, he saw Ruef as a scapegoat.

“Ruef is in prison because he has confessed to taking money from a corporation president many times richer than himself,” Older said. “Then why isn’t the corporation head in prison for bribing Ruef? Fourteen years in a cell is too heavy a penalty to pay for another man’s crime.”

Odler launched another crusade—this time, to get Ruef out of prison. But Fisher had moved beyond ridiculing local politics: by the end of the year, Mutt was being nominated to run for President of the United States. And he’d met “little Jeff,” who, an inmate in an insane asylum, imagined himself to be James Jeffries, the heavyweight boxing champion. Before long, the relationship between the scheming Mutt and the idiotically innocent Jeff would take the strip out of political satire altogether and put Jeff’s name with Mutt’s in the marquee.

Campbell tells how Bud Fisher went on the vaudeville stage, assisted by a former St. Louis cartoonist named Tom Mack. This could be the Mack that eventually ghosted the strip for Fisher from about 1915 until Mack died in 1932 (after which his assistant, Al Smith, took over the production)? Most sources say Mack’s given name was Ed, but since it’s all clouded in vagaries, maybe it was Tom.

Campbell gives us lots more to savor. And his writing manner is casual and conversational with occasional diverting detours but laden with obscure tidbits at every turn. Don’t miss it.