I’ve been a rabid fan of Lauren Weinstein’s work since my friend Becca gifted me a signed copy of Weinstein’s 2008 book The Goddess of War, published by PictureBox, when we were both confused twentysomethings. Here was something totally unexpected-work that, in tone, harkened back to Shary Flenniken, Trina Robbins and Diane Noomin but blended its feminist humor with whip-smart observations about world history and Norse mythology.

Not only that, but Weinstein’s work seemed stylistically sui generis-I’d never before seen a cartooning sensibility that incorporated Victor Moscoso, the German Expressionists, Fort Thunder and the Monster Roster. Reading back over that book, I find myself baffled that she wasn’t snapped up for television like Lisa Hanawalt, another master comedian.

Part of Weinstein’s appeal has always been her disarming frankness. Girl Stories, a collection of autobiographical shorts published in 2006 by Henry Holt, was blurbed by both Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti. Like those cartoonists, Weinstein is a master at spinning humor from pathos, and her stories for kids are just as sharp and observational as her stories for adults.

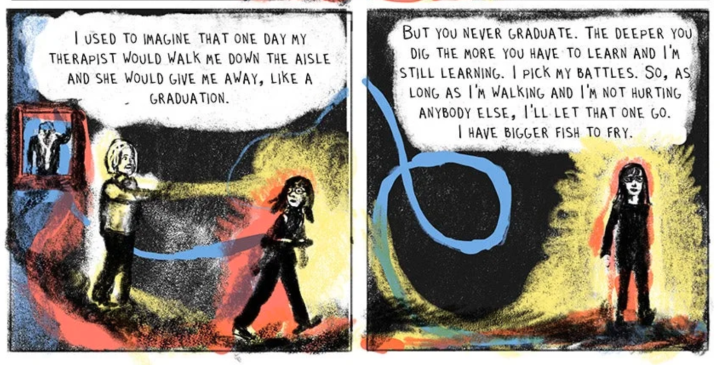

Since the mid 2000s, Weinstein has expanded her practice to incorporate a humor strip (the short-lived but beloved Normel Person, for the Village Voice) and comics journalism, with motherhood providing the subject matter for a number of recent shorts. When I read her 2018 piece Being an Artist and a Mother with the students in my comics journalism course, I had to fight back tears, even though I’ve read it a number of times. “Why did I assign this piece?” I asked the class. Why is it so powerful?” My students overwhelmingly cited Weinstein’s emotional honesty. Her comics speak to the id. They leave space for interpretation, a defining characteristic of great art.

The same story forms exist in comics journalism as in print journalism: the editorial, the feature article, the explainer. Comics journalism has exploded in popularity since the early 90’s, when my personal aesthetic, and, I assume, Weinstein’s, was forming. Traditionally, I’ve been allergic to work that looked slick or digital, and storytelling that eschews the id, but something interesting has happened as I age. I’ve become less rigid, and more open to the idea of comics playing a variety of cultural roles.

Explainer comics, such as Archie Bongiovanni’s A Quick and Easy Guide to They/Them Pronouns, A Quick & Easy Guide to Sex and Disability by A. Andrews, and Guantanamo Facts by Nomi Kane, which opens Sarah Mirk’s Eisner-winning collection of reportage on Guantanamo Bay, do exactly what they’re meant to do: convey information in a clear and accessible way. They don’t work in the same way that feature articles do, nor are they intended to. It's like comparing In Cold Blood to a cookbook. The artfulness of the former doesn't diminish the usefulness of the latter.

There are a dizzying variety of approaches to non-fiction graphic storytelling. It would be silly, for instance, to compare Sarah Glidden’s on-the-spot reportage to Derf Backderf‘s historical recreation of the massacre of student protesters at Kent State. I’m naturally drawn to artists, like Derf, who trace their lineage back to Gonzo journalism, and their visual language to artists who flourished in the underground papers of the ‘60’s and ‘70’s-it’s impossible to overstate the visual influence of Speigelman on Sacco, for instance, and those RAW artists were a key touchstone of Weinstein’s as well. Whereas some contemporary comics journalism comes across as sanitized and easily digestible, Weinstein’s packs the aesthetic gut punch punch I prize in all storytelling, fiction or nonfiction.

The best comics journalists, including Joe Sacco and Ben Passmore, demonstrate a level of self-awareness that’s critical when attempting to tackle stories interrogating class, race and power. Weinstein’s willingness to self-examine makes her the perfect candidate to tackle a topic as fraught as domestic violence, which she’s been doing for the past year and a half.

The Gift of Time, excerpted on Slate.com in September, is woven from oral history interviews with the residents of the Town Clock Development Corporation (henceforth called TCDC), a live-in domestic violence shelter in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Time, in the work’s title, refers to the shelter and its mission. Unlike transitional housing, which typically requires that residents leave after six months at most, The TCDC, which has eleven beds (of 14 in the entire state of New Jersey), allows residents, most of whom have children, to stay indefinitely while they heal and gather the resources and documents necessary to start new lives. This approach ensures the women are less likely to return to their abusers out of financial necessity, but it’s also expensive. Most of the residents have legal bills. Many are attempting to gather the documents they need to begin school or find jobs, without reliable computers or wifi. All are coping with trauma.

The shelter’s administrators are also stretched thin. Christine Edwards, the TCDC’s programmer, a single mother, works at a mental health facility and is studying for her master’s in social work.

Time also refers to the time Weinstein has spent with the shelter’s residents, thanks to a grant from CoLABarts, a New-Jersey based arts organization with a mission to “engage artists, social advocates, and communities to create transformative new work.” In addition to chronicling their lives, the artist has been leading a series of cartooning workshops for the shelter’s residents.

These workshops were initially chaotic. When most Americans think of comics, they think of superheroes, and Weinstein was skeptical of Christine Edwards’s prompt for their first class that the women imagine themselves with superpowers. A lack of childcare meant the participants often had to come and go from the classroom without making significant progress on their drawings.

After the first several classes, however, a volunteer babysitter was obtained and the women were able to focus. It’s one of the many small victories that Weinstein chronicles in this spectacularly moving piece.

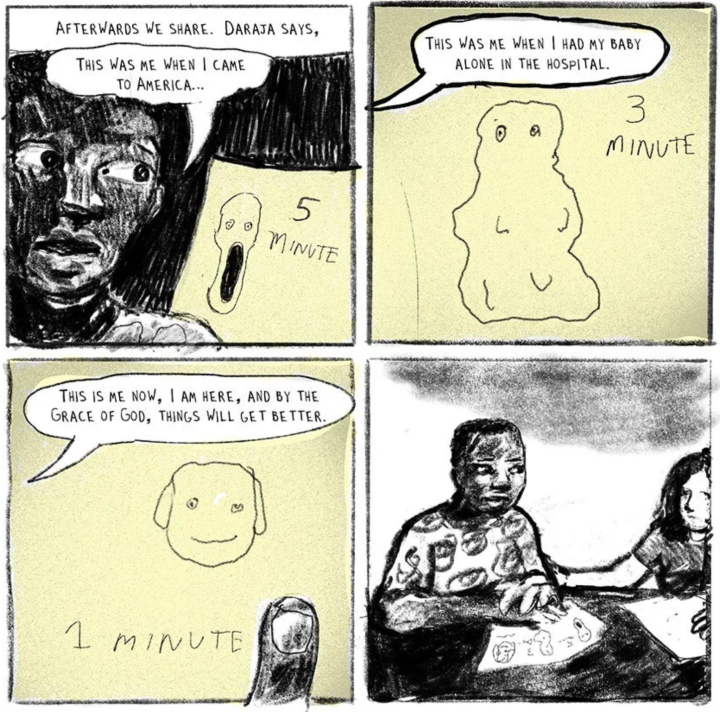

Svetlana and Daraja, two of the residents whose lives Weinstein chronicles in detail, began to find their respective voices and grow their artistic practices. This progress is representative of increasing autonomy in other aspects of their lives.

One of the strengths of comics journalism is its slowness. We’re inundated at all times with clickbait headlines designed to terrify.

By contrast, it can take a comics journalist years to craft a feature article of moderate length. Collecting and transcribing interviews, then choosing what to keep in and what information to leave out, can be crazy-making, but it produces works that ask big questions about morality, about privilege, about what it means to be human, about how to spend our time on this planet. What superpower would you choose if you could choose anything? This question carries a lot more weight depending on whether or not you feel powerful to begin with.

Weinstein grapples with her own relative privilege, but also zooms out to examine the structures, like our judicial system, rigged to keep the powerful in power, to intimidate the vulnerable and to steal their time.

How do we reclaim this time? The old adage “Time is money” seems facetious, but it’s fundamentally true. Organizations like the CDC and CoLABarts deserve more funding. Not only that, but they should be replicated in every community.

Weinstein concludes the piece with a quote from Christine Edwards, who observes that “success is not about whether you succeed or fail, it’s about making a decision and seeing it through.” In seeing this project through from start to finish, Weinstein has succeeded spectacularly.