I’ve been reading Mike Dawson’s stuff for a long time, since his graphic novel debut Freddie & Me (Bloomsbury, 2008; an autobiographical story about his love of Queen and his experiences as an English immigrant to the U.S.), through Troop 142 (Secret Acres, 2011; a story about how boys are gross), Angie Bongiolatti (Secret Acres, 2014; activism, charismatic people), Rules for Dating My Daughter (Uncivilized Books, 2016; a compilation of shorter pieces), his work for The Nib and his Instagram comics. The Fifth Quarter, out from First Second, is yet another publisher and, in some ways, his highest-profile project. It’s been interesting to watch his lines simplify as he experiments with his style. This is the usual direction for cartoonists, who start out putting a pattern on anything they can and then realize that there are diminishing returns to that kind of effort. Freddie & Me was crowded with stuff, full of teeth and text, blobby noses and carefully hatched flooring. If you put it next to The Fifth Quarter, you can tell it’s the same artist, but he’s holding so much back now, putting more effort into the story -- which no longer reads as just one thing after another -- and trying to see how little he can put on the page while still communicating.

When I interviewed Dawson in 2016, he said, “When my daughter was a baby, it was easy to feel like she was safely cocooned in a world that consisted only of her and her immediate family. As she grows older, the more the outside world creeps in, and how little it feels like we as parents can control it. That produces many emotional responses, including anger and anxiety.” The Fifth Quarter seems a natural outgrowth of those feelings, focusing on a fourth-grade girl (Lori) who really wants to play basketball, but is stuck on the pre-game team that doesn’t get to score real points. The topic is a good fit for First Second, and the book feels like it belongs in that publisher’s catalogue. It’s not too experimental, but it’s also real comics, well-colored and structured by a professional. Shadows are often a point of weakness in mass-market comics produced with an eye to a cash grab, but here they’re soft and smart, simple but undistracting.

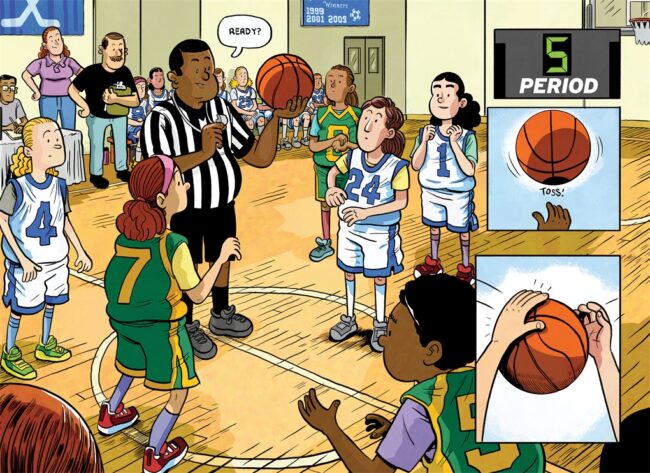

Dawson used to work mostly in physical media, but he did this book on a Wacom Cintiq, and it feels both digital and good, something I probably should say more often than I do. He puts in some nice brushy effects that you don’t see unless you look closely, but serve to rough up the sometimes too-shiny neatness of the digital line. He still loves noses, but he’s reduced his palette of them to simple arcs and curves that evoke Chic Young and Mort Walker. They have character, but they’re not distracting. The panel structure is straightforward: simple in quieter moments, full of overlapping rectangles during basketball games (to evoke the variety of inputs one has to process as a player or a spectator in that game). The first page of the book, a single big panel, is a strong beginning, well-composed and introducing all of our major themes (basketball, fourth-grade girls, nervousness, a desire to win) without being messy or crowded. There are good two-page spreads throughout, incorporating a lot of characters but not look-at-me showcases.

Some of Dawson’s previous books have been wordy. His Instagram comics tend to be on the chatty side, heavily narrated as he talks about something or other that’s bothering him, or mocks himself. The Fifth Quarter communicates more through imagery and its characters’ body language than through dialogue. Sometimes Dawson even removes facial features when they’re not needed to do a job. A character’s nose might go away, or her mouth, or sometimes both. Eyebrows do a lot of lifting.

The Fifth Quarter has an interesting take on competitiveness, too, that one can read as a subtle message about white privilege. It’s not anti-competition, but it’s definitely not fueled by a libertarian spirit either. The way Lori and her friend grow apart because Lori sees participation in basketball as a zero-sum game is a small example of the way white Americans are terrified of losing whatever advantage they have gained and, therefore, step on the folks on the ladder rungs below them.

It’s hard for me to say whether the book captures what it’s like to be a fourth grade girl, partially because that was a long time ago for me and I’ve forgotten those feelings, and partially because Lori’s parents are as important to the story as she is, and, as a parent, I’m more likely to sympathize with them than with her. Far from the trombone-voiced adults of a lot of comics (I’m lookin’ at you, Jeff Kinney), they feel like real humans, dealing with their own shit: corralling children of various ages, running for office, frustrated with each other and the kids when they realize they’re not working as a team. I don’t think the book ever tips over into being about adults rather than kids, but maybe it’s more about a family than about fourth graders, which makes it readable by grown folks as well as ones who are still growing.