Zap Comix didn’t kick off the underground press scene of the sixties, but it serves as a model of what was at stake in the shift from the button-down, nuclear-family '50s to the radicalism and drug culture of the '60s and '70s. Zap also illustrates an alternative history of the visual art of the period, a story that runs counter both to the predominance of abstract modern art and to mainstream comics’ subservience to the Comics Code Authority, which formed in 1954. But this is a merely a thumbnail of Zap’s significance, one I had long taken for granted. I realized that although I’d read, say, Crumb’s “My Troubles with Women” and Rodriguez’s “Evening at the Country Club” and had long loved Moscoso’s wraparound Mr. Peanut cover for issue #4, I had never thought about the comics that went into an issue of Zap in concert with one another, much less with the entire series. In thumbing the pages of Fantagraphics’s five-volume set (six, if you consider the clamshell case housing limited-edition prints of the seventeen covers), I began to feel as though I hadn’t known Zap very well at all.

This mammoth edition offers the ideal opportunity to examine the way the periodical evolved, not only in terms of the interaction among its artists but also in terms of subject and form. Granted, one doesn’t require a lavish, $500 version to do this—a humbler, more portable edition would do the trick—but reproduction values count for a lot here: the sixteen issues, as well as a seventeenth that was previously unpublished, are reproduced over four volumes on a thick paper stock and at slightly larger than full size, and have been scanned from negatives. Simply put, they look fantastic. The fifth volume is a retrospective one: it includes an oral history compiled by Patrick Rosenkranz, author biographies, a brief time line, archival photographs, gatefolds of the five wraparound covers, and other ephemera. The oral history covers the essential points in the narrative of Zap’s history—how the magazine got started and how all the players came together, how they influenced and worked with one another, their conflicts and arguments, censorship, the magazine’s legacy, and so on—yet it sometimes seems lacking. It’s valuable as a framework and in understanding certain strips in the comix, but the stitched-together conversation feels thin in places, and certain readily available details are inexplicably missing (for example, the name of Crumb’s publisher who absconded with the files for the first issue). One wants more of it—if not from the artists themselves, then from those they worked with (and those they didn’t) and from some of the myriad cartoonists they have influenced since issue #1 appeared. “Without Zap there would be no such thing as alternative/literary/artistic/self-expressive comics and graphic novels,” Chris Ware has said. “Zap started it all.”

Crumb might have disagreed about that first part: “Comics are different [from literature], and when cartoonists try to elevate the form, so to speak, it’s in danger of becoming pretentious.” Yet he did elevate the form: though he did not transform it into literature, in the way that, say, Art Spiegelman, Daniel Clowes, Alison Bechdel, and Ware have, he set it on a parallel trajectory. He made comics “For Adult Intellectuals Only,” as the cover of Zap #1 declared in 1968. The adult part of that statement—which also served as a warning—announced the graphic content between the covers; these were not the Sunday funnies. The inclusion of the word intellectual, though, indicated that this wasn’t purely salacious material—that it was meant as revolt as much as it was meant to be revolting.

Crumb drew the first two issues in two months in a fit of energy and inspiration. In the months previous, he had written a handful of strips for various underground periodicals (Griffin, for instance, had seen his work in Yarrowstalks before they met to work on Zap). Zap #1 appeared in December 1967; Crumb and his first wife, Dana, famously sold it from a baby carriage on the streets of Haight-Ashbury. The other issue, however, which was written first and was intended as issue #1, wasn’t published until after #3 had appeared because Brian Zahn, Yarrowstalks’ publisher and Zap’s ostensible first publisher, disappeared with the files. Crumb redrew the entire issue from copies, and it finally came out as Zap #0 in December 1968.

Issues #0 and #1 contain some of Crumb’s best-known characters, including Mr. Natural, Flakey Foont, and Angelfood McSpade as well as the “Keep on Truckin’” strip (about whose popularity he later complained, “Was I a ‘spokesman’ for the hippies or what?”), yet the comix are in some ways less incendiary than one might imagine. On the cover of issue #1, a figure in the background references Milt Gross’s famous dictum “Is diss a system?” Gross upended cultural conventions with his ethnic malapropisms and parodic pratfalls, and this first issue of Zap partakes of that tradition. The strips mostly concern middle-class anxieties and offer jokey takes on hippiedom, kiddie pranks, and modern art. The issue opens with an evocation of a kind of EC lunatic buoyed by Mad’s nutty sensibility: Crumb’s mad scientist, whose plan presumably is subversion, is toothless; his closing threat is “Kitchee-koo, you bastards!” The cover of #0 seems more promising: it features a nude figure curled in the fetal position being given a jolt of electricity that is fed into his body by an umbilical extension cord. “The comic that plugs you in!!” he declares. But plugs you into what? In the first strip, Mr. Sketchum the cartoonist lays it out for us: we can expect “thrills and laffs” and “the latest in humor.” Not exactly the provocative material for which Zap is famous. Crumb’s influences are conspicuous: his cartoonist-guide treads past copies of Mad and Humbug strewn on his studio floor. (In a drawing from 1967, either before or during the time he was making the first two Zap issues, Crumb drew a tame version of this cover for the unpublished “Kozmic Komix.” It shows an anthropomorphic, vaudeville-esque lightbulb plugged into a wall outlet declaring, “The comic that plugs you in.”)

The germ of Crumb’s genius is here; his artistic talent—his ability to think and to draw in various styles—is on display, but the storytelling is watered down, the gags flat. Even with his stylistic abilities, the strips feel alike tonally and in terms of subject, and knowing what’s to come in future issues, the work seems especially constrained. Though Crumb felt that, on close inspection, the issue’s psychedelic notes were evident, he also admitted that “Zap didn’t look like something from the hippie counterculture. It looked like an ordinary comic book.” Interestingly, Gary Panter thrilled to the first issue (he saw it in 1969) not because it broke with the past but because it resembled old comics—Popeye and Gene Ahearn’s Our Boarding House. Crumb, Panter has opined, “had synthesized the previous seventy years of comics into some kind of beat wise-guy wised-up kind of comics.”

Still, these first efforts were a thumb in the eye of the Comics Code Authority and a strong addition to the growing underground-press scene. The first printing of issue #1 was five thousand copies, which sold out in a few months, but Zap didn’t hit its gloriously perverse stride until issue #3, when the entire group had assembled. However, even by issue #2 the tenor of the publication had changed: Crumb recruited Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso based on their psychedelic poster work—examples of which were pasted all over San Francisco—and S. Clay Wilson had joined up by way of poet Charles Plymell, who, with Don Donahue, published Zap #1. (When Wilson arrived in San Francisco, he went to visit Plymell and found Donahue running the first issue of Zap on a Multilith 1250: “When I came in the door—clankety-clack, clankety-clack, pages of Zap, pages of Zap.”)

Crumb is still in Mad mode in issue #2. His cover boasts “gags, jokes, kozmic troothes,” and in the strip “Angelfood McSpade,” he describes the titular character as “‘Zap Comix’ Dream Girl of the Month,” a thin reference to Basil Wolverton’s gruesome “Beautiful Girl of the Month” on the cover of Mad #11 and a comparison all the more troublesome given Crumb’s caricature of Angelfood as a “savage” black woman. (To be fair, Williams makes a similar reference to Wolverton in issue #16 with a grid of gruesome faces under the heading “Children of a Lesser God … Way Lesser!”) Crumb also signs off in this issue (and again in issue #3) as “the happy hippy cartoonist” and furnishes the motto “A Cartoon for Every Occasion,” a reference to, or perhaps a holdover from, his career as a greeting-card illustrator.

Crumb’s temperance is at odds in issue #2 with the contributions from his new cohorts. Griffin’s strip on the inside front cover—a trippy experiment with the nine-panel grid and nonnarrative sequential art—bucks the qualities Crumb has set out on the cover, as does Moscoso’s two-page wordless, pop-psychedelic comic, “Luna Toon.” Griffin and Moscoso came from the world of illustration and design and had attended art school (though Griffin, like many comics artists of the sixties and seventies, found his tastes at odds with those of his professors). Griffin has created a poster using sequential art and the two began collaborating on posters. They also made plans to start a comics magazine just before meeting Crumb and being invited to join Zap. Still, Moscoso saw a distinct difference between what he and Griffin were concerned with and what Crumb and Wilson were up to: “What is life? Life is a sequence of one event after another, and Rick and I were much closer to reality in our absurd, non-linear use of the comics form than Wilson and Crumb, who were definitely and obviously lifelike, since they were drawing like life.” The quality they all shared, right from the start, was a disinterest in making “acceptable” or socially “valid” art. Comics, for Griffin, served as a way of avoiding this entanglement: “creating an art that had the appearance of comics,” he said, was “a throwback to a period of time when I could care less about the status quo.” Moscoso tells a story in which Griffin shows up with a design for psychedelic lettering that doesn’t actually say anything. “It’s amazing,” Moscoso recalls, “how many people have come up to me and told me what that said—like a Rorschach.”

No other Zap artist better exemplified a complete rejection of cultural norms than Wilson, whose presence in the group was highly influential. “Wilson drew any crazy idea that came into his head, no matter how twisted or violent or sexually weird or whatever,” Crumb recalls. “I used to draw stuff like that that I threw away. I suddenly realized, ‘Why the fuck do I censor myself?’” Crumb’s concern in these early issues with appealing to an audience was anathema to Wilson. Wilson’s aim, as he put it, was not “to entertain [the masses] but to enlighten them. Or to make them sick. One or the other. Sometimes it happens simultaneously.” He had been drawing comics for more than a decade before joining Zap and had made himself into a kind of outlaw: he rode a motorcycle, got kicked out of ROTC, joined the army only to quit, and, predictably, found his interest in figuration mocked in art school. The Checkered Demon, who debuted in issue #2, is the id incarnate: lascivious, cunning, and beastly. But then nearly every Wilson character is a version of this. Issue #3 introduced “Captain Pissgums and His Pervert Pirates,” a horrifying crew of utter degenerates: “They came from every crud-crusted corner of the globe, these lice-infested losers… Some were sadists… Some were masochists… Some just licked stinky ol’ boots… And the captain settled for having his crew whiz into his mouth while others looked on delighted.” In recently recalling the way he, as a young artist, looked to Zap to find examples of what could be done in comics, Ware admitted that Captain Pissgums “scared me to death.”

In photographs in volume five of the set, Wilson appears larger than life, flipping off the camera and grinning maniacally. His onetime girlfriend Nadra Dangerfield has argued that art “was the way he explored himself, expressed himself, entertained himself, excoriated himself, exonerated himself, celebrated himself.” The comparison is not a one-to-one relationship, as Wilson himself has pointed out: “I am not the characters I draw, I am the artist that draws the characters, or, in other words, just because I depict evil does not mean that I am evil.” In interviews, he references Freudian and Jungian psychoanalysis, and he has claimed that his violent, cum-drenched stories are “therapeutic,” adding, “My pen is my shrink.” But by and large, he tends to offer superficial responses when asked about the intense psychopathy and brutality in his work. “I have this morbid fascination with deviancy and I like drawing it. I find it entertaining,” Wilson has said. It’s sometimes difficult to see past the rough subject matter in his Zap comics—women fare particularly badly—but his early comix are significant, at the very least, for transgressing social and cultural boundaries so profoundly that there could be no going back. If Griffin and Moscoso were expanding what comics could be, then Wilson was expanding what they could be about, and bringing everyone along with him.

Jeet Heer has argued that Wilson is the central artist of the underground generation because his unhinged, unashamed comics gave Crumb and others permission to untether their own work from personal censorship and social taboos. But Zap was perhaps as important to Wilson as Wilson was to Crumb and others. When he attended art school in Nebraska, Wilson found that figurative art fell deep in the shadow of Abstract Expressionism and that his teachers had little regard for comics. He stuck with figuration but, as Crumb tells it, had “lost his confidence” in comics. Wilson came to San Francisco with a portfolio of drawings in hand (Plymell had published them in Kansas as 20 Drawings by S. Clay Wilson) and found his way to Crumb and to Zap, which reinvigorated his interest in the medium. There’s no doubt that Wilson would have continued making art and may even have found another way back into comics, but it’s interesting to consider whether the ferment of the group helped engender the characters that made their first appearances in Zap or whether simply having an outlet to express his ideas in this form ensured that their stories would be told.

In any case, Wilson’s extreme example encouraged both Spain Rodriguez and Robert Williams, who described Wilson’s comics as “vulgarly lyrical.” Both joined the group with issue #4, following Gilbert Shelton, who had come on with issue #3. Shelton had been writing his Wonder Wart-Hog strip while a student at the University of Texas, in the early sixties, and Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers for the Austin Rag. (Williams wonders, with good reason, whether Shelton, not Crumb, was the first underground cartoonist.) His drawing style resembles that of Sergio Aragonés, Mad’s most prolific cartoonist and also an inveterate joke-teller. Shelton’s aim was to write funny comics, a quality, he felt, that set him apart from the other Zapsters. His Wonder Wart-Hog is a buffoon, an anti-Superman whose lust rivals, and frequently befuddles, his attempts at heroism. Wonder Wart-Hog is highly entertaining and reads like classic comic strips yet with a deeply lascivious twist and a subtle, though sharp, satirical streak. A pot comedy, starring the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, in issue #5 reflects the general fear by publishers at the time of being arrested by the police for pornography (Zap #4 had been busted). In the event that police discover their illicit activities, the brothers construct an elaborate trap in their apartment in order to delay the cops while they flush their stash. Though the strip concerns pot possession, it ends with a sideways reference to the magazine, when Fat Freddy gets caught in the snare and is repeatedly electrocuted: “Don’t flush the... ZAP stash! Don’t flush it!! It’s only me!! ZAP! ...only me! ZAP! ...only me! ZAP! ...only me! ZAP!”

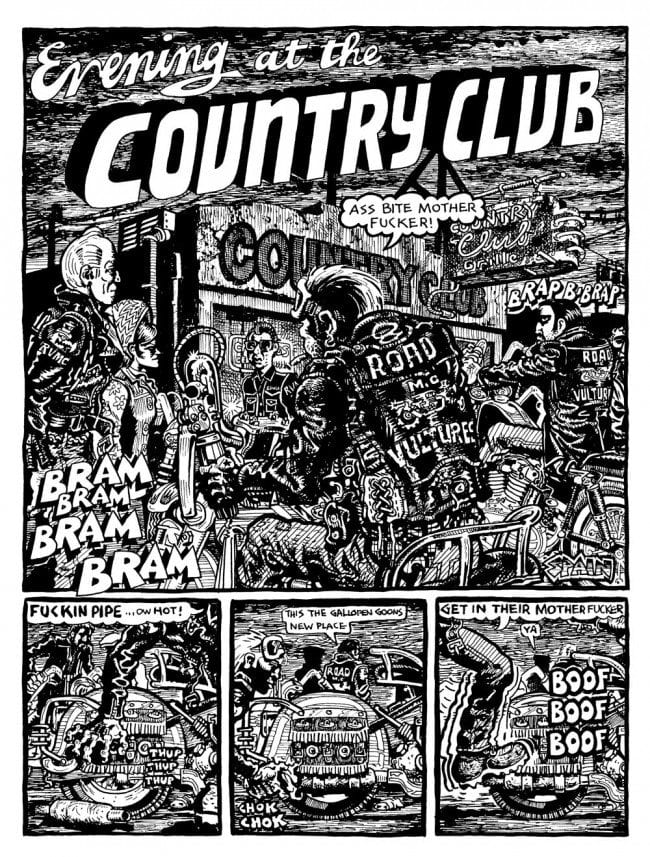

Rodriguez’s affinity for Wilson's work stemmed from their shared love of the biker scene. As he had for Crumb, Wilson inspired Rodriguez to push further into unexplored territory. His first story for Zap was “Mara, Mistress of the Void,” which mostly concerns a fight between two butch women over a man. It feels uninspired, as Rodriguez comix go, with none of the depth that characterizes his best-loved work. He had come to San Francisco in 1969 only for a visit and shortly returned to New York, where he was working at the East Village Other. He sat out issue #5 and then moved back to the West Coast in time to contribute to issue #6. That number featured “Evening at the Country Club,” in which Rodriguez began mining his own experiences for material. His contributions bear the closest resemblance to short stories, and, through the course of the issues, they become increasingly sophisticated, with real-life details that lend the narrative authenticity. He is easily the most politically engaged of the bunch. In New York, he had been involved with an anarchist group whose platform proved too radical but whose determination, Rosenkranz notes, he admired. A photograph in volume 5 shows Rodriguez being escorted away from a Vietnam War protest by no fewer than four mounted policeman. Trashman, his Marxist working-class hero, appears in two issues of Zap. He is a complicated, very adult superhero—a tough alternative to Shelton’s boisterous nitwits. By later issues, Rodriguez develops a balance between white and black spaces that is stunning, particularly in stories, like those of Trashman, where there is more dark than light; the pages appear as if lit from behind.

Williams cut his teeth working for Big Daddy Roth in the mid to late sixties as Roth’s art director. In 1969, he wrote to Shelton and Crumb inquiring whether he might contribute to Zap; Shelton offered him half a dozen pages in issue #4, and Williams gave them “The Supreme Constellation of Dormasintoria,” a ribald interpretation of “the big bang theory” as Metropolis meets a Kirby space god in an erotic intergalactic fable. Williams was already an accomplished artist—he had been making what he termed “supercartoon” paintings that resemble an entire comic drawn in a single panel (think Mati Klarwein or Öyvind Fahlström) while working for Roth—and his early contributions to Zap are quite polished. Yet Zap was a formative experience for him; he found a freedom there that would shape the course of his life and art. “I was so happy to be with Roth where I could use my imagination to great extremes,” he says, “but when I got into Zap I just pulled out all the stops ... I feel very successful today because of Zap Comix.”

The addition of these three—the only new members until Paul Mavrides was asked to join in 1998, and then only because Griffin had died in a motorcycle accident seven years before—made the group complete. The photographs of the Zap Seven (or, as Crumb calls them and as I kept thinking of them, the Magnificent Seven) throughout volume 5 are often as absorbing as the comix. There’s one of Williams (who reminds me of a contemporaneous Mike Kelley) sitting next to Basil Wolverton in 1972. A photograph of a fresh-faced Griffin at age nineteen alongside another of him only eight years later but looking utterly changed: with long hair and beard, posing with religious imagery in his studio. Rodriguez ensconced among rocks in the Arizona desert in 1971, looking every bit the rugged warrior he created in Trashman. Easily the oddest photograph in the book is the shot of Mavrides, Rodriguez, Crumb, and Wilson placidly drinking Frappuccinos in a Starbucks in 2009. The volume also contains a series of photographs that capture all seven Zapsters. One, from the early seventies, shows the magnificent seven lined up on a street corner. Five of them stare across the street into the camera. Moscoso turns his face away, and Crumb, at the far end of the line, leans into the street to glimpse the lineup.” We were a goddamn rock band,” he enthuses at the start of the volume—and the images bear it out.

The history of the periodical isn’t only notable for the comic itself but also for the collective business practices that developed around it. After issue #2, the four artists then working on Zap—Crumb, Moscoso, Griffin, and Wilson—formed a legal partnership, called Apex Novelties, and trademarked the name Zap. They also entered into an agreement with Don Schenker at Print Mint, who agreed to cover the costs of the offset printing and art reproduction, while the artists retained copyrights to the comics and film from which the issues were printed. Once sales of each issue had paid off Print Mint’s expenses, the artists and the printer split the profits.

Shelton, Williams, and Rodriguez became part of the partnership, too, and Rodriguez saw the collectivization as an act of generosity on Crumb’s part, given that he had founded the comic on his own. Rodriguez also characterized the group as a collective “made up of the most uncollective guys there are.” His observation is true both of the varying styles and concerns that came to define Zap and of the attitudes and opinions each member, for better or for worse, brought to the table. Conflicts among the artists seem never to have concerned content, but decisions regarding the logistics of the group were occasionally fraught. The most divisive disagreement involved the question of who might contribute to the comic. Once the original seven were settled in, Crumb wanted to include more artists in the mix in order to increase the frequency of the issues and to allow a multiplicity of voices, but this idea was “kiboshed most vigorously.” “I felt particularly bad about the exclusion from Zap of plenty of artists,” Crumb says. “I did not want to be part of a conservative, exclusionary group like that.” Zap was an exception in this regard; the spirit of the era tended toward more open, free-flowing endeavors, as Diane Noomin, who contributed to Arcade, Wimmen’s Comix, and other underground periodicals in the seventies, recalls: “In a way, it was like Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney saying, Let’s put on a show, kids. If you wanted to, you’d say, Let’s put on a comic, kids! and you asked all the people you liked to be in it.” But Zap didn’t invite other people to join. A background speech bubble in the comic jam “Circle of Jerks,” in issue #15, pokes fun at their exclusionary practices: A group of kids hidden behind a fence are trying to join in the action (which is sexual, naturally) occurring on the other side. “If we take out one of these panels we can get into the inner circle,” declares a wanna-be. Crumb felt that by 1973 Zap had become the establishment, but he found himself in the minority. “I describe Zap as a democratic anarchy,” Moscoso says, “which seems like a contradiction, but somehow—it is! We are a contradiction. We are also the longest-running underground comic book going.”

Zap was unique among other hippie publications of the era for the cohesiveness of its issues perhaps for the very reason Crumb decries. And yet the seven artists are, as Moscoso put it, “more different than… similar.” Those differences can work harmoniously, as they do in the Zap jams, which began with issue #3 and continued regularly throughout the series, even resulting in a group-wide tiff over Crumb’s decision, in 1968, to no longer participate in the jams—all of which culminated in a series of strips in Zap #14 telling the story of the argument. (A minicomic consisting solely of jams is also included in the set.) The non sequiturs and different drawing styles abutting one another within and between panels prefigure the postmodern cartooning best illustrated by the latter part of Panter’s Dal Tokyo strips; it seems impossible that sense might be made from the chaos and nonmeaning, but the elements blend together miraculously, and one can almost see the seven cartoonists sitting around the large library table in Wilson’s apartment passing around pages, hurling jokes and insults, and feeding off one another’s contributions.

Crumb claims to have begun losing interest in Zap by the early seventies, partly because he felt the exclusion of new members had made the publication somewhat stale. The experimental qualities that made the first several issues so exciting, however, gave way to increasingly mature efforts. Williams, always a stylistic master, contributed comix that seamlessly joined different styles, such as “Masterpiece on the Shithouse Wall,” in issue #6, which merges an etched-looking prehistoric story with Fleischer-esque cartoony action, and, in the same issue, “A Flash in the Pan,” a highly detailed two-page drawing that looks, impossibly, as though it were cast from mirror-polished stainless steel. Wilson’s work, already quite packed with detail, seems to become increasingly so. He referred to his style as “Belgian lace from Hell” or a “Chinese toy store window”—the idea of overpacked, but thoughtfully constructed images—and drew these intricate and teeming panels with the aid of a magnifying glass (volume 5 contains a photograph of filmmaker Nicholas Ray reading Zap #4 with a magnifying glass; one wonders if he was looking at a Wilson drawing). He also began executing one-page drawings that are exhaustive with detail, the pages so tightly collaged together that the constituent parts aren’t easily distinguishable from one another. Moscoso began using more dialogue in his comics, which possibly suggests that he became more comfortable with the comics medium, seeing it not just as an outlet for formal experimentation but as a way to play with different kinds of narrative. His contribution to issue #7, “Loop de Loop,” is a remarkable surrealist, interdimensional play between Disney cartoon characters, Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo, and his own quintessential fluid psychedelia. Yet there is still no clear beginning, middle, and end to the story. The title itself bears this out: Moscoso put the words of the title in a circle and added an extra de so that it reads as a never-ending loop: “Loop de Loop de Loop de Loop...”

In the early seventies, Griffin became a born-again Christian. His work already expressed a kind of mysticism (his nickname among the group was Mystic Rick)—his cover for issue #2, for instance, illustrated an aspect of Gnosticism as seen through a psychedelic lens—but his comix expressed decisively religious, though still hippyish, subject matter by issue #6. His comic in that issue, “Omo Bob Rides South,” rendered in a gorgeous, heavy chiaroscuro, reads as a parable of earthly sin and resurrection. Though Griffin continued to push the formal possibilities for comic art—these later comix are nothing if not beautifully and inventively drawn—his aim in making comix was now higher: “The only reason I’m drawing Zap Comix is not to assert myself as a great artist, but it’s basically to be a witness for Jesus Christ, because I think he’s coming soon.” Issue #6 also contains Wilson’s “Angels & Devils,” a strip, dedicated to Griffin, in which Wilson juxtaposes the doings of angels and of devils, rendering the angel’s goodness as implausible and concluding that the two groups are not as different as one might imagine. Although there was room in Zap for such conflicting belief systems, it set Griffin as the odd man out, as Moscoso once observed: “He dropped out for a while, ’cause we were the handmaidens of the Devil. He goes to Christ, you know, what’s he going to do? Draw for Zap Comix, the smut mongers?”

Crumb’s contributions throughout the series are interesting in part because we see him entering into subjects that have occupied his desires and his intellect (which were not always in agreement) for his entire career and finding a way through the blast of id for which he’s famous into a more considered, more nuanced treatment of the same subjects. Crumb’s initial foray into psychedelic comics was motivated by LSD trips—he has described sex and record collecting as “addictive indulgences”—but he stopped taking LSD and other drugs in the seventies when they no longer provided ample inspiration. “I started to work on the drawing,” he recalls, “started improving again, through the late ’70s and in the early ’80s.” Sex continues to be a theme in his work, but his treatment of it has deepened, from impulsive and self-regarding to an interest in the “collective myths” of sexuality and ecstasy as well as a mellowing of his sex drive (at least on the page). Though still populated by women whom he desires to “conquer and degrade,” Crumb’s comix become more honed and less indulgent. Perhaps it is a function of his coming to understand, and not just acknowledge, what Wilson once called “the murky recesses of your psyche.”

Trina Robbins accused the Zap artists of ruining comics, arguing they’d encouraged male cartoonists to follow suit in degrading women. There’s scant discussion of this legacy of Zap in the collection; it’s disappointing that the history in volume 5 doesn’t engage more with this subject, given the prominence of women in the comix and in the underground scene and given the period—the prime of the women’s liberation movement—in which they were made. Suzanne Williams, Robert Williams’s wife and an artist herself, would have been a valuable addition to the conversation; she married Williams before he became involved with Zap and no doubt has a unique perspective on the inner workings of the group and on the way they were perceived. Rodriguez recalls a woman complaining that the artists of Zap “had the wrong attitude.” “And she’s right,” he continues, “we do have the wrong attitude. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be out there and people shouldn’t hear what we have to say.” Wilson, on the other hand, is typically blunt: “I draw what I want. That’s the whole idea behind underground comix.” Williams makes a curious assertion: “the Zap artists were probably more pro-feminist than any other males in the world.” It’s hyperbolic, but an interesting claim that, sadly, goes unexplored here.

Aline Kominsky Crumb’s drawings appear in some of Crumb’s strips in the final, previously unpublished issue. It’s a kind of secret history of the magazine: its ninth contributor was a woman. These strips also represent some of Crumb’s most complex and mature efforts: they show him engaging with the same issues that appear in his early work—his attitudes about his own body, his lust, his erotic hang-ups—but he’s no longer in the echo chamber of his own id. He’s in dialogue with a real woman who speaks back to him in her own voice. Wilson’s use of the pen as therapy seems more apt in relation to Crumb’s late strips with Aline than they do to Wilson’s own work, the subjects and treatment of which don’t change much over the course of the issues.

The deviancy and extreme violence in its pages is largely what set Zap apart in its early years. The comic broke ground for a host of publications that followed quickly on its heels, many of which were created by members of the Zap Seven. But the feelings expressed in extremis by the Zapsters weren’t conjured out of thin air—those ideas, emotions, and desires had been seething and intensifying in the repressive postwar atmosphere of the United States. Williams has noted that “the government was trying to stretch 1955 another two decades and it just wasn’t working.” EC and Mad relieved some of the pressure by parodying the uptight fifties, but Zap completely upended the era, rejecting its values and tenets and laws. It came as an explosion, moving what had been underground into the light of day.

American culture was only just waking up to graphic nudity in its publications, underground or otherwise. Playboy and Penthouse readers were well-versed in the female form, but pubic hair didn’t appear in adult publications until 1970 (though those magazines were showing teasing wisps in 1969). Zap’s clits, tits, and dicks may have been drawn, rather than photographed, but the contexts in which the nudity appeared, particularly in the work of Crumb, Williams, and Wilson, was sexually explicit and, in that sense, freshly subversive. “Anything before that was just some secret thing,” Williams says of Zap’s groundbreaking foray into nether anatomy. In 1969, Bhob Stewart curated an exhibition (the unfortunately titled “Phonus Balonus Show of Some Really Heavy Stuff”) for Walter Hopps at the Corcoran Gallery, in Washington, D.C., and included work by Crumb, Rodriguez, and Shelton. If some of the imagery in Zap had only just been introduced to men’s magazines, then its very public presence in a national museum was astonishing. Williams may have said it best: “They weren’t showing cunts and dicks back in 1970 at a major museum. What the hell?” Hopps’s recognition of Zap’s significance, not retrospectively but when the series was in its prime, testifies to the fact that it wasn’t merely a product of its era but defining force. Rodriguez likened Zap’s importance, and that of underground publications as a whole, to the American Revolution: the “anything goes” attitude, the “fuck you” attitude.

Given Zap’s longevity and its stunning level of influence on individual cartoonists as well as its fearless approach to subject matter, it’s amusing to consider retrospectively the judgment handed down during the 1969 obscenity trial on the East Coast over the sale of Zap #4: that the court was unable to understand how “the cartoonists were ‘original,’ or how they were ‘influencing a new generation of cartoonists’ or how they showed ‘enormous vitality.’” The details of the trial itself occasionally have the flavor of a comic book: the clerks and booksellers accused of dealing the work were discovered by the so-called Morals Squad, and the court declared the magazine a part of the “underworld press.” “It is hard-core pornography,” the court concluded, adding, “perhaps that type of obscenity contains its own antidote and eventually becomes a repetitious bore.” There is some truth to this observation. Though Zap ran for another four decades, it could not maintain the kind of shock in, say, 1994 that it perpetrated on readers in 1969. The years since Zap’s inception have seen a proliferation of graphic and illicit comics, films, novels, and other materials; one wonders if we are capable of being shocked in the way we were forty years ago.

The novelist Tom McCarthy recently wrote about James Joyce’s Ulysses, itself a victim of censorship, that “a certain naive realism is no longer possible after it, and every alternative, every avant-garde manoeuvre imaginable has been anticipated and exhausted by it too.” Zap didn’t exhaust the possibilities of form. Comics—more so perhaps than any other medium, given that it deals in words and pictures—seems inexhaustible in all its variety, and the Magnificent Seven partook in an already rich cartooning heritage. McCarthy’s summation of Ulysses’s legacy has a note of finality about it, that novels are forever treading in its wake. Zap, on the other hand, ploughed a course through to an open field, in which the routes available to new cartoonists were innumerable. But the first part of McCarthy’s statement might just as easily be said of Zap. Its creators made impossible any return to the past. Art should not be tidy, they said, nor should it always be polite.