White supremacy is, as it always has been, alive and well in the United States of America, but so are the forces that seek to eradicate it. In August of 2017, racists and fascists convened in Charlottesville for the Unite the Right rally, but counter-protestors were also in the streets, at great risk to themselves, to deny the racists and fascists unimpeded access to a place and a platform for their hateful message. Some gave their lives to do so. It has long been a hallmark of American culture that when police have killed unarmed black and brown people, the people who survive them get in the streets to protest the injustice of it.

Under the management of newly-elected President Joe Biden, the gears and levers of a hollowed out bureaucracy are wheezing and sputtering back to life. The full force of our Rube Goldberg administrative apparatus is starting to bear down on a laundry list of impending crises, including an ongoing pandemic, a mounting climate catastrophe, and an economy teetering on ruin. The marginalized communities who have been advocating a bold reimagining of justice in America will soon learn if the moderate voices who joined in their calls for justice under Trump will continue to do so under Biden, who has signaled he is not as motivated to move too far afield of the status quo. Biden acknowledges the need for change, but with the usual caveats, conditions, and qualifiers of a moderate Democrat. “Protesting such brutality is right and necessary. It’s an utterly American response. But burning down communities and needless destruction is not. Violence that endangers lives is not,” Biden said in response to the protests of George Floyd’s death by police in Minneapolis in May of 2020. It’s a position that deliberately misses the point. It is precisely because violence is endangering that action is needed. In light of comments like these, the response to police violence and oppression by social movements like Black Lives Matter seems practical, yet, still, it is often deemed too radical.

It is to this landscape that writer David F. Walker and artist Marcus Kwame Anderson deliver The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History, a thorough, if sober, retelling of the rise and fall of the militant social movement of the sixties whose influence is still felt today. It is an ambitious undertaking, but the pair largely stick the landing, especially when considering the venue, a mainstream publisher, and the audience that will result from that venue, readers who are unfamiliar with the story of the Black Panthers. The legacy of Black Panthers resists simplification, but readers will come away from A Graphic Novel History with a greater understanding of the conditions that informed the formation of the Black Panther Party and the people who led the group, orchestrated its rise, and, in some cases, were party to its dissolution. Walker tidily encapsulates the premise in “The Myth of the Panthers,” the book’s opening chapter. “The Black Panther was a complex organization that had an equally complex relationship with the communities it was dedicated to serving,” he writes. But while Walker acknowledges that the myriad social problems of the Black Panthers’ era persist, he stops short of drawing parallels between the Black Panthers and the contemporary social movements taking up similar work.

To be fair, it would be difficult to do so with such limited space. But Walker’s narrative choices, especially in addressing the decline of the Black Panthers and the fates of its members, casts the story as a cautionary tale, rather than one of empowerment. In framing it this way, however, Walker underscores just how invested the country’s security apparatus was in undermining the ambitious work the Black Panthers were doing to build solidarity within their communities and removing the platform given to them by a media engaged by their sensational tactics. “It is impossible to know for sure what the Black Panthers could have been had they not been targeted and undermined by the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO),” Walker writes in the book’s Afterword.

To be fair, it would be difficult to do so with such limited space. But Walker’s narrative choices, especially in addressing the decline of the Black Panthers and the fates of its members, casts the story as a cautionary tale, rather than one of empowerment. In framing it this way, however, Walker underscores just how invested the country’s security apparatus was in undermining the ambitious work the Black Panthers were doing to build solidarity within their communities and removing the platform given to them by a media engaged by their sensational tactics. “It is impossible to know for sure what the Black Panthers could have been had they not been targeted and undermined by the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO),” Walker writes in the book’s Afterword.

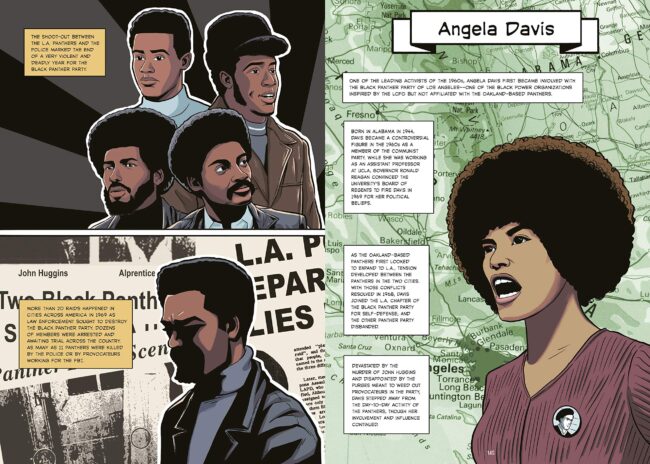

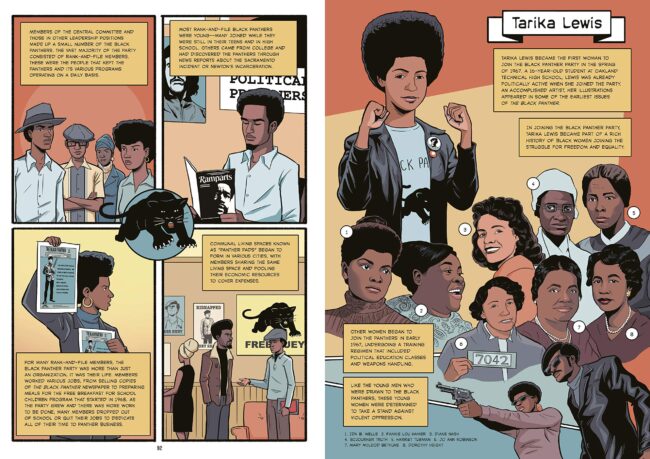

Walker began work on The Black Panther Party after completing The Life of Frederick Douglass. While scripted like a comic, complete with panel descriptions, the dominant mode of storytelling in the result is more illustrated history than comics narrative, dominated by warm depictions of the players in the story. Much of Marcus Kwame Anderson’s portraiture, though beautifully rendered, is set against sterile geometric backgrounds. Too often, it has the effect of de-contextualizing, stiffening, the subjects he is depicting.

Much of the story is told with caption panels. The pages are dense with them. Anderson’s concise, inventive layouts help to keep the steady info-dump visually interesting. He utilizes a color palette that is largely subdued, so when he opts for a bold color choice, it is deeply felt. When rendered against a background, his expert use of light and shadow gives his figure work raw humanity. This is especially true in the sequences highlighting the on-the-ground work the Black Panthers were doing in their communities, such as the free food program that put 10,000 bags of free groceries in the hands the Black Panthers’ Oakland community.

Anderson also employs graphic motifs that go a long way in unifying the book and providing a sense of scope to the story of the Black Panthers, such as the superimposition of portraiture against a background map of the region in which the person depicted was from. This device succinctly showcases the diversity of personalities within the ranks of the Black Panthers, as well as the reach of the group.

Anderson also employs graphic motifs that go a long way in unifying the book and providing a sense of scope to the story of the Black Panthers, such as the superimposition of portraiture against a background map of the region in which the person depicted was from. This device succinctly showcases the diversity of personalities within the ranks of the Black Panthers, as well as the reach of the group.

While they are not prevalent, there are some truly sequential narratives presented in The Black Panther Party. Walker and Anderson seem to have reserved these sequences for the most pivotal moments of the story. They are the highlight of the book because it is in these panels that the radical nature of the Black Panther Party is on full display and given its fullest context. One such sequence occurs early in the narrative. Founding members Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale engineer an initial confrontation with police in Oakland and get them to stand down by demonstrating that the Black Panthers are fully aware of their rights. Newton steps out of his vehicle, holding his firearm with confidence and dignity in an image that encapsulates the Black Panthers’ militant ethos. In another, the Black Panthers get lost in the California capitol building while trying to locate the assembly chamber in order to deliver Newton’s Executive Mandate #1 and protest Bill AB-1591, a gun control bill which was introduced on the heels of altercations between the police and the Black Panthers while the group was guarding Betty Shabazz, the widow of Malcolm X. Scenes like these illustrate that organizing power is done by trial and error and by testing tactics. They illustrate that enacting change or at least attempting to is something that is attainable, though not without consequences. Risk and threat are present in these sequences, as well.

The Black Panther Party is intelligently told. The episodes and asides of which it is comprised congeal quite naturally into an informative whole that will engage all readers, but especially those who are unfamiliar with the Black Panthers’ story. At times, it suffers from a lack of context, but, again, space limitations likely preclude traveling too far afield of the subject matter and Walker and Anderson do their best in creating windows through which deeply curious readers can seek more information, as in the conspicuous placement of piles of books with titles and authors visible in the foreground of a scene in which Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale discuss what they want their new organization to accomplish and what they want to call it. As he notes in his Afterword— (written in May of 2020, while Minneapolis was burning in protest of George Floyd’s killing by police)— assessing the Black Panthers’ legacy invites mixed emotions and Walker is careful not to commit too much of their rhetoric.

“During the process, my opinion of some members of the Party changed drastically—and not always for the better. But what any one of us thinks about the Panthers—be it positive or negative—doesn’t matter nearly as much as the fact that our feelings should be derived from a place of knowledge and perhaps even some nuance,” he writes.

Part of that assessment must also include the parallels between their time and our own. In his afterword, Walker names recent victims of racial violence at the hands of police and “concerned citizens.” He names George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor. It’s an incomplete accounting of those lost to racial injustice. He goes on to compare the fates of Tamir Rice and Dylann Roof. “Never let us forget that in the United States, Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old Black kid, was killed by police in 2014 for holding a toy gun, while the following year, Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old confirmed white supremacist, was arrested without harm after he killed nine Black people in a South Carolina church,” he writes. The societal problems that the Black Panthers sought to remedy persist to this day. Their legacy of radical organizing does, as well.

Part of that assessment must also include the parallels between their time and our own. In his afterword, Walker names recent victims of racial violence at the hands of police and “concerned citizens.” He names George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor. It’s an incomplete accounting of those lost to racial injustice. He goes on to compare the fates of Tamir Rice and Dylann Roof. “Never let us forget that in the United States, Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old Black kid, was killed by police in 2014 for holding a toy gun, while the following year, Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old confirmed white supremacist, was arrested without harm after he killed nine Black people in a South Carolina church,” he writes. The societal problems that the Black Panthers sought to remedy persist to this day. Their legacy of radical organizing does, as well.

Black Lives Matter is not mentioned in the Afterword, nor is there any reference to the social movement within the text. Given the complex legacy of the Black Panthers, it is possible that Walker does not want to invite comparisons out of fear that he will taint the social movement by drawing comparisons to the oft-maligned Black Panther Party. Not to do so, though, is to deny the empowerment the Black Panthers exemplified and the lessons they taught subsequent organizers. Social movements are fluid and change is won by inches. The Black Panthers espoused ideas that were antithetical and outright threatening to the status quo. Their victories were won by an unapologetic embrace of a radical vision. Walker opens his book with a quote from Fred Hampton. It reads: “We’ve got to face the fact that some people say you fight fire best with fire, but we say you put fire out best with water. We say you don’t fight racism with racism. We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity.” This is actually part of a longer statement. A longer excerpt of the speech goes like this:

“We don’t think you fight fire with fire best; we think you fight fire with water best. We’re going to fight racism not with racism, but we’re going to fight with solidarity. We say we’re not going to fight capitalism with black capitalism, but we’re going to fight it with socialism. We stood up and said we’re not going to fight reactionary pigs and reactionary state’s attorneys like this and reactionary state’s attorneys like Hanrahan with any other reactions on our part. We’re going to fight their reactions with all of us people getting together and having an international proletarian revolution.”

The longer excerpt is far less palatable to a mainstream audience, but it is also a far more specific and representative depiction of the Black Panthers’ ethos. Given further context, it would come into sharper focus still. To dilute their message, or to sanitize it, is to reduce their legacy to symbolism and deny what they achieved in their communities in service to a radical vision of dignity for the marginalized and oppressed.