Could the colorful Hergé-inspired trilogy Charles Burns concludes with Sugar Skull be read as a formally audacious sequel to his black-and-white masterpiece Black Hole? "A hole is never just a hole," Burns has said of the series, which launched in 2010 with X'ed Out and continued two years later with The Hive. And the lacunae, tunnels, cavities, orifices, and other absences so present in these three books cover a lot of the same creepy-ass territory as their diseased-adolescence predecessor – although his trademark meticulously rendered deformities are relegated to a fantasy realm. This time around the emphasis is on the biological consequences of the sexual desires thrumming though Burns's young fertile creatures.

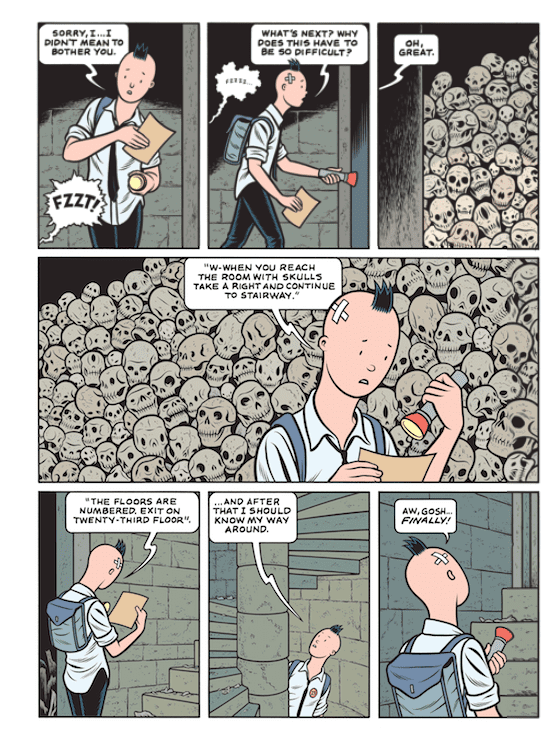

Besides providing a delightfully Freudian read with heavy emotional repercussions, Sugar Skull also offers a final opportunity to enjoy the trilogy in all its fine Franco-Belgian drag prior to the inevitable single-volume repack. Hergé has been called a thieving magpie of imagery, and Burns wreaks artistic justice by inverting both Hergé's narrative style and star. Tintin becomes Nitnit, the oneiric representation of Doug, whose three-stage development from the late-seventies art-punk wannabe who calls himself Johnny 23 to a slacker record-store clerk several years later is chronicled. Snowy the dog becomes Inky the cat, who leads Nitnit down a grungy hole on X'ed Out's first page and returns for the trilogy's uncanny conclusion. (Burns's books are also littered with desert skeletons reminiscent of the dead dromedaries Hergé snagged from photographer J. Pascal Sebah and dropped into The Crab With the Golden Claws.)

The Nitnit sequences dreamily reconfigure Doug's life into surreal pastiche of Hergé's adventure stories and William S. Burroughs's sexually charged Midwest-meets-Middle East Interzone, which college-aged Doug invokes through his onstage spoken-word cutup shtick. To confuse further, both Doug's and Nitnit's worlds contain Ladies’ Special Dream Man, Throbbing Heart, and Young Love – three titles for a single generic early-sixties romance comic whose stories mirror Doug's relationship with Sarah, a masochistic brunette bombshell being stalked by her ultraviolent ex, Larry (who bears an eerie resemblance to Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh). One Hive panel even depicts Doug reading a Nitnit volume called The Hive, in which he presumably will read the aforementioned romance pamphlet narrating his life. Mind the abyss, dude!

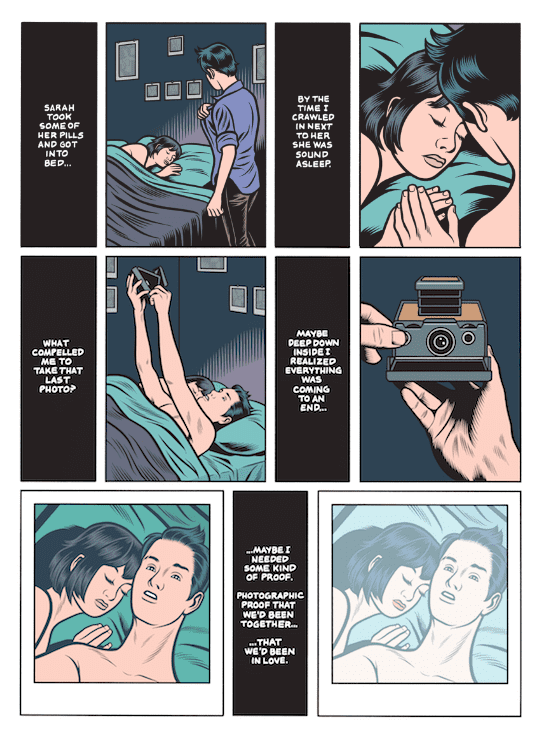

Having read The Hive ourselves, we know something traumatic has happened between Doug and Sarah, although precisely what has yet to be revealed. (Both Doug and his Nitnit alter-ego have also been shown recovering from head injuries, the latter with a jaunty X patch on his skull.) Burns has been laying on the visual clues heavily, however: Interzone eggs fashioned after Hergé's The Shooting Star, fetal pigs, Madonnas, and a raven-haired breeding queen all herald Sugar Skull's revelation about Sarah's pregnancy. Doug's inability or refusal to assume responsibility for his (unaborted) child becomes the psychic engine that drives Burns's beguiling but ultimately seamless 162-page narrative.

Early in The Hive, Suzy, a sassy breeder in the titular apiary, reads a remarkable sequence, drawn in impeccable romance-comics mode, which summarizes the story thus far. (Burns has often in interviews mentioned having given a girlfriend a similar stack of comics in his youth.) Suzy, Nitnit, and we as well all learn that the Sarah character, described as already having had abortions that "really did a number on her head," is finally dating a "normal" guy when her violent ex shows up. Suzy's pleasure in the text is frustrated by a two-issue gap, which Nitnit will rectify by procuring the missing issues; Sugar Skull, meanwhile, will serve the same function for us.

Early in The Hive, Suzy, a sassy breeder in the titular apiary, reads a remarkable sequence, drawn in impeccable romance-comics mode, which summarizes the story thus far. (Burns has often in interviews mentioned having given a girlfriend a similar stack of comics in his youth.) Suzy, Nitnit, and we as well all learn that the Sarah character, described as already having had abortions that "really did a number on her head," is finally dating a "normal" guy when her violent ex shows up. Suzy's pleasure in the text is frustrated by a two-issue gap, which Nitnit will rectify by procuring the missing issues; Sugar Skull, meanwhile, will serve the same function for us.

After learning of Sarah's pregnancy, Doug wishes only to escape his responsibility. (Did I mention that this is also a horror story in which the monster is the female reproductive system?) Retribution arrives in the form of Larry, whose hallway attack Burns renders as in a single flickering eighteen-panel page. Doug's fear turns to laughter as lizard-brained Larry pummels him offscreen. The narrative cuts to the Interzone, where Nitnit is expelled through one of the many waste pipes we have seen through the series and virtually shat, or vomited, into the river that is another ongoing motif. It is a river both of nostalgia and desperation. Nitnit's dreamland escapes represent a wish fulfillment Doug cannot enjoy in reality. He has always already returned to his (always unseen) mother's basement, where his father used to live. Doug dons Dad's bathrobe, discovers his pill stash, and sinks into a slough of addictive despond.

The feeling throughout these books is the sort of regretful fatigue we experience in anxiety dreams. "Reality is for those who cannot sustain the dream," Slavoj Zizek has said, and while Doug grows up biologically, he threatens to repeat his – and his father's – mistakes unto the generations. "I've got a good life," he thinks prior to visiting Sarah for the first time since her pregnancy. In truth, he's a recovering alcoholic subsisting on an adolescent diet of cigarettes, Pop-Tarts, and coffee as he pores over old photos and patronizes his girlfriend, who strongly resembles his pre-Sarah squeeze.

As carefully and colorfully coded as a Douglas Sirk "women's picture," Burn's trilogy concludes realistically with a long-delayed meeting between Elvis-sideburned Doug and a seemingly grounded Sarah. After a final flutter of the empty rectangular panels – the pregnant pauses – that have signaled the books' transitional miasmas throughout, Nitnit makes one last appearance. Animal carcasses and skeletons lie along a desert roadside, and a ruin-dwelling resident wields a knife as if to defend his child from the wanderer. Nitnit stops by a roadside shrine decorated with eggs and sugar skulls in memory of a dead child who, in Doug's real world, is very much alive.

"After you get past the surface details," Suzy the breeder explains to Nitnit at one point, all romance stories are "pretty much the same... But for some reason I never get tired of reading them." Charles Burns is all about surfaces and details, of course, and this story is ultimately a not-unfamiliar tale of love and regret. When Nitnit finds his resting place, it too is sadly, even hauntingly familiar. Burns's power lies in exoticizing the ordinary, alienating the quotidian, and showing that every sad life has the makings of an adventure story.