The most important thing to remember about King Arthur is that there was no King Arthur. Most people, I dearly hope, know that already, although that might be giving too much credit to public education on either side of the Atlantic.

But it’s not really enough to say there was no such person as King Arthur, and no such place as Camelot; certainly no such thing as a Round Table staffed by the bravest and most steadfast warriors in the kingdom. No, it’s worse than that, if you can imagine: there was never even any singular literary source. What we know as the myths of King Arthur were constructed, painstakingly, by hundreds of sources over the course of about fifteen hundred years. It’s a process that began in the hazy epoch following the departure of the Romans from ancient Britain and which continues onward to this very day.

That’s the part that sticks out, for me: no one literary source, no single authority. So many aspects of the story we recognize as being integral are relatively recent inventions. The look and feel of so many modern adaptations was nailed down in the late 19th century. Between Tennyson and the Pre-Raphaelites, the Victorians went a long way to solidify our conception of the medieval. The Romans didn’t have stirrups; no one in Europe did until long after the era in which Arthur was supposed to have lived and died. Anachronism has always been a part of the tapestry.

No one interpretation of Arthur has primacy over any other. It’s all (more or less) fantasy. The “Matter of Britain” was the literary preoccupation of hundreds of years of European history. Some of the most recognizable elements and characters were the inventions of French and German authors in the Late Medieval Period, writing about the wild frontiers of ancient Britain in much the same spirit as Europeans making cowboy films in Italy in the 1960s. The reality was always incidental to the myth. The very idea of “chivalry” was a late development, a Christian warrior code with little parallel in the brutal realities of medieval warfare. But it proved remarkably ineradicable once introduced, and indeed forms the cornerstone of some of the most powerful and enduring iterations of the legend.

All of which is to say: if I tell you that StarHenge is a decidedly modern iteration of the myth, it shouldn’t surprise you that it's an adaptation thoroughly scrubbed of just about any influences past approximately the 12th century. No Lancelot, no Sword in the Stone, certainly not an iota of chivalry to be found. At the same time, this is a compulsively metatextual narrative, conscious of contemporary debts both to and from. The fecundity of Arthur as source material is explicitly broached at every turn. References abound to more contemporary fare - everything from The Terminator to Doctor Who to—seemingly inevitable—Star Wars come up throughout. At first it almost seems annoying - do you really need to have a snarky narrator making constant references to “wibbly wobbly, timey wimey” and “a galaxy far, far away”? Well, after some consideration - that’s sort of how these things have always worked. Each successive iteration of Arthur is defined by what it takes and what it leaves behind, and the degree of obeisance to whichever sources it identifies as primary. A process often explicitly earmarked within the texts themselves. Neither The Terminator nor Doctor Who, and certainly not Star Wars, would exist without being able to build on endless iterations of Arthur.

Now, please - forgive me a bit of wandering across the map. I spent a considerable time in grad school studying just this subject. Sadly, my shelf of Arthuriana is in a box in a storage unit a couple hours away. Well, maybe not so sadly, for your sake, because then I’d probably be tempted to pull out my Gildas and brush up on my Malory and this review would be even more otiose. That’s kind of the problem with Arthur. Pulling out one’s Gildas might just get you arrested, depending on the precinct.

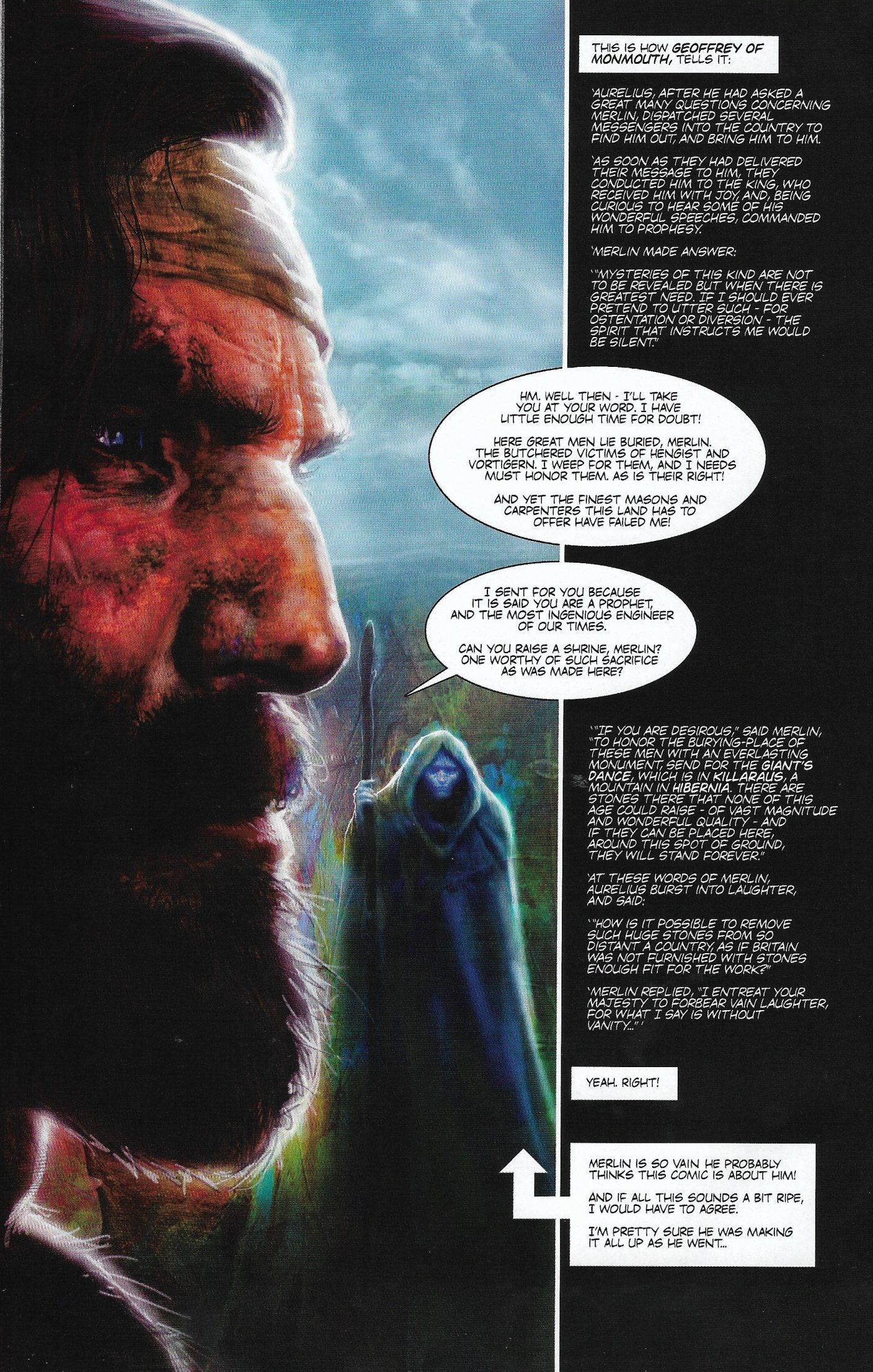

With that said, the first question that comes to mind is a question of form. This series does a lot of telling - an immense amount of telling, for better or for worse. It is for long stretches an illustrated book, with passages of excerpted text from sources such as Geoffrey of Monmouth. There’s a section from a fictional lost book of Taliesin, used to describe the final days of Arthur and his war with Mordred. Many readers will simply balk at walls of text on the comics page - i ain’t reading all that, i’m happy for u tho, or sorry that happened. It’s become practically axiomatic - comics used to be so much more verbose, modern readers have no patience for all that, yadda yadda. Which strikes me as a condescending thing to say regarding the education level of modern readers, but it's nevertheless a common sentiment in the 21st century.

All of which is to say - yes, there are a lot of words in this comic book. The writer in this instance is the same chap doing the art, so you can hardly say he’s getting in the way of himself. Or perhaps you could, if you were the type of jackal who uses the phrase "Bronze Age" as a derogatory adjective. I don't know where Liam Sharp finds the time to be a novelist, but he's taken to writing books without pictures in his spare time. He understands perfectly well that putting more words on a page of comics means that page of comics takes longer to read. Seems a simple concept, I know... but if he had wanted to write StarHenge as a prose novel, that's well within his skill set.

What Sharp has in mind seems significantly more ambitious than that. Firstly, this is a retelling of the life of Merlin - specifically, Geoffrey’s Merlin, from the Historia Regum Britanniae. That’s one of the earliest chronicles to show us an iteration of Arthur that might be recognizable as our Arthur - still, as I say, no Round Table, but there’s a King named Arthur, son of Uther Pendragon, who is slain in a final battle with his nephew Mordred. The interesting thing about Geoffrey that is often obscured in later iterations is just how much the legend was influenced by the echoes of the traumatic decades following the withdrawal of the Romans from the British Isles. Because, yes - at its heart, Arthur’s story is a postcolonial narrative. The Romans ruled Britain for 400 years, and when they abandoned the islands at the end of the 4th century they left behind a populace who had long become culturally Roman. Britain was Roman for 400 years, until one day they weren’t. Geoffrey’s text still seethes with resentment at that fact, all these centuries gone.

And all the successive waves of conquerors and rulers all looked for legitimacy in the legacy of the mythic hero who fought the invading hordes of Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Badon. You may have caught me hedging with the “more or less” a few paragraphs back - well, the legend of Arthur begins there, one war to serve as the pebble of facticity in the heart of a thousand years of accreted fantasy. And just the fact that post-Roman Britain fought to repulse the same Anglo-Saxons who later adopted Arthur as their own mascot should give you an idea of just how that contest played out. Eventually the Normans came along, and in turn they took Arthur for their purposes as well.

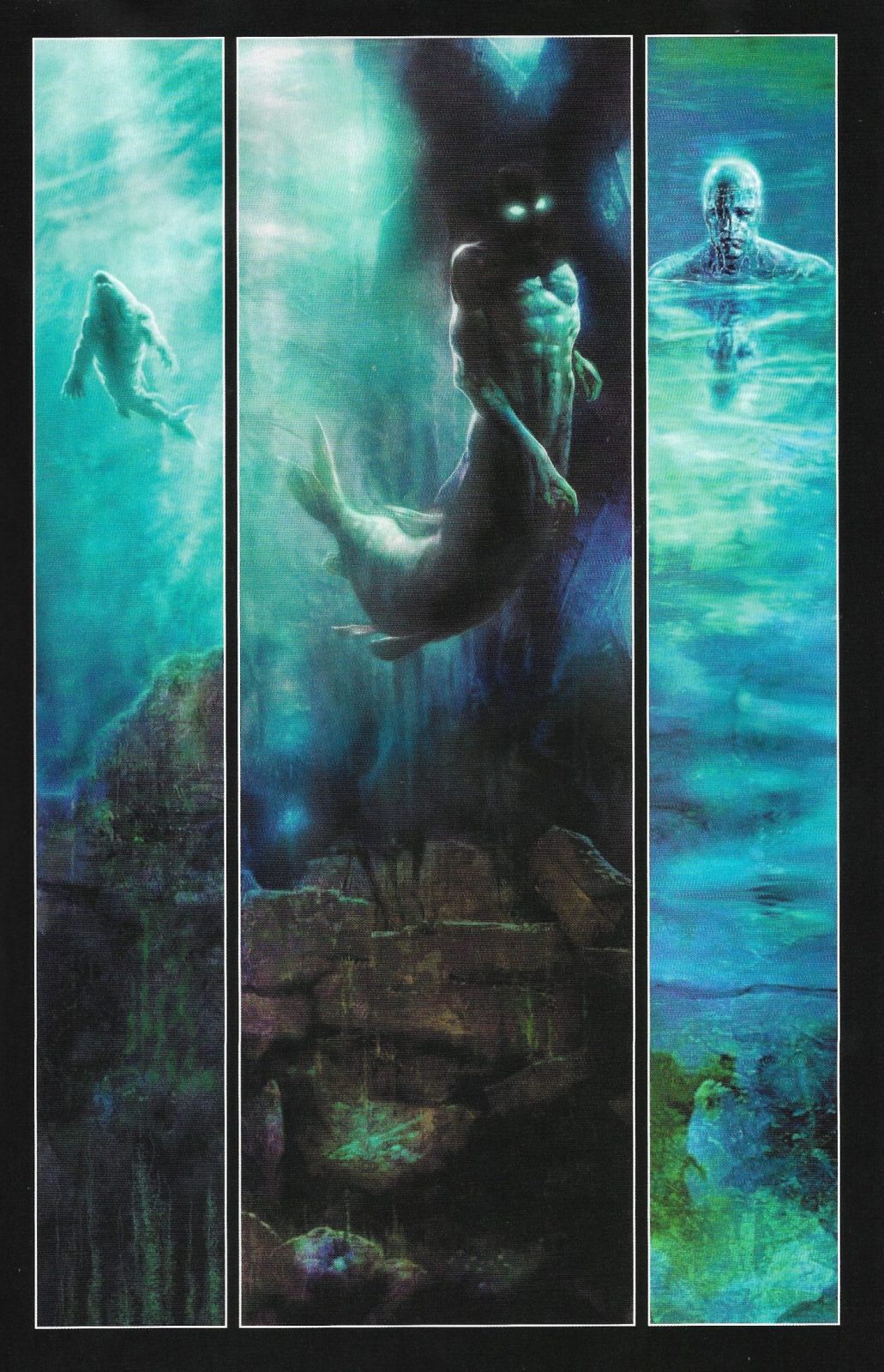

But StarHenge is not just a life of Merlin - it’s also a saga about the last war of the human race, hundreds of years in the future, hounded unto extermination by an alien AI known as The Cast, who live in humongous H.R. Giger cathedrals floating between the stars and cover themselves in the skin of their enemies. Who we know as Merlin is a traveler from this future, sent back in time to sow the seeds of resistance against a seemingly unbeatable foe - there’s your Terminator. Of course, he carries a premonition of futility: how exactly is he supposed to build the foundations of a victorious future, two millennia down the line, by manipulating the bloodlines of handful of medieval British kings? Beats the hell out of me, and still an open question by the end of Book One. Perhaps The Cast win and create a new Arthur in their own image, because that’s what you do when you win a war on the British Isles.

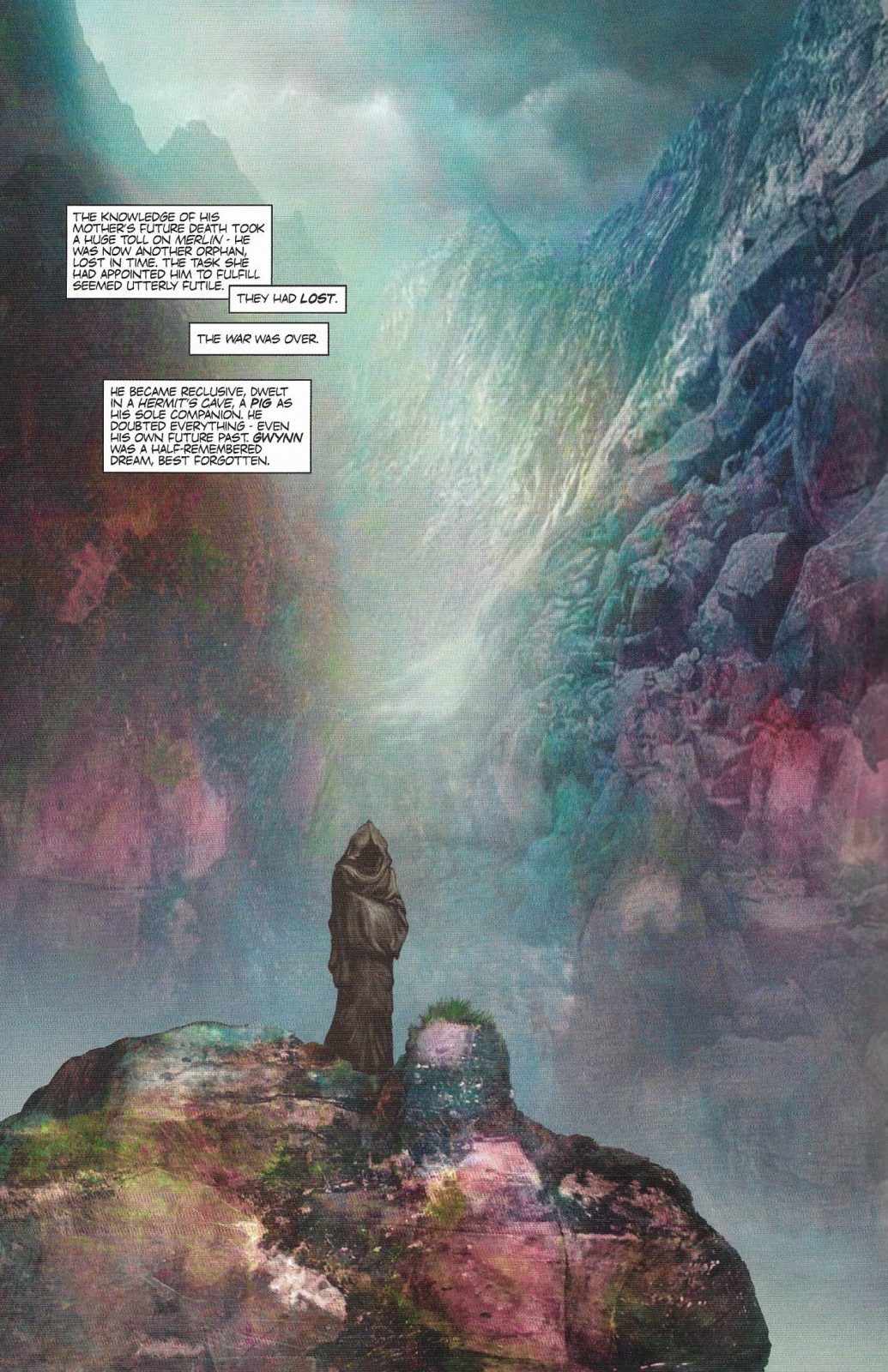

That sense of inescapable fatalism is one of the overriding themes of most versions of Arthur. This is very pointedly not a story about searching for the Holy Grail, but the Grail myths are the perfect illustration of the point: they never actually find the damn thing. The act of searching is itself discrediting - and, of course, here’s where the myths often circle around to very explicitly Christian messages of faith and forbearance. If you need to search outside yourself for concrete evidence of faith you have already lost. But the idea of a quest somehow frustrated at its origins, of a futile mission that must still be carried through - that’s Merlin here, fighting like Canute to stem the tide of history with very paltry means indeed. How’d that go for Canute, again?

The other track of the story, separate for the moment from the trail of mythic wizards, is a present-day plotline featuring young lovers Amber and Daryl. He’s a football hero and she’s into Wicca - though, as we learn, her roots go deeper into the mysteries than is first apparent. It’s in these sequences that Sharp really stretches his legs, so to speak. Because, if we’re being frank here, we all know Liam Sharp can do some pretty fantastic dark fantasy art; we know he can do a dead-on Frazetta in his sleep - and sure enough, issue three indulges our innate human desire to see homages to the ol’ “Death Dealer” himself. But he can also do a dead-on Giger, which you don’t necessarily see every day. And then he can pull out for a photorealistic grayscale that brings to mind (let’s throw a recent name into the mix) Jay Anacleto. There are also passages of a more “Bigfoot” cartooning style that on first glance I ascribed to Sharp, but are attributed in actuality to special guest artist Matylda McCormack-Sharp. Attractive pages, redolent of the likes of Dave Cooper. Good enough to make you wonder why you haven’t seen more from her before, and to make you hope to see more soon.

My favorite section comes at the beginning of the fourth issue, where Mr. Liam Sharp seems to be channeling... Mr. Liam Sharp, circa 1992. There’s a killer robot from the future, see, and I’m not going to say it’s the spitting image of a certain jolly blue killer cyborg from from the far-off future of 2020, but - well. Such a resemblance must be purely in the eye of the reader, yes? Sharp busts out the Ben Day dots and gives us some of that “old-fashioned” pen & ink hatching that I love so much. A very talented man, very good in a number of different genres, but you should know me by now. I always want to see more good old-fashioned crosshatching. I want to see your hand pulling against the grain of the board.

The very first words of the story are a quote from Geoffrey: “Woe unto the red dragon, for his end draws near.” If we’re laying all our cards on the table, you should probably know I did a whole paper in grad school tracing the symbol of the red dragon, stemming from this precise sequence. There’s lots of stuff about Welsh dragons in The Mabinogion as well, material I imagine (hope?) Sharp might get to eventually. It is therefore difficult to imagine a comic book more perfectly attuned to my interest and expertise. So the question before you, dear reader, is whether or not the book works quite so well if you haven’t literally spent years studying medieval British literature at the graduate level.

I dearly hope the answer to that is yes - it’s a stylistic tour de force, and a not inconsiderable feat of scholarship to boot. The story presented here is only the first part of what should be a much longer epic. A few scattered references to the Knights of the Veldt strongly seem to imply future installments will fold in other, later aspects of the myths. Tristan and Gawain and the like, maybe. I dearly hope we get those stories. I’d like to have a nice fat stack of these on my shelf to sit next to Nennius and Malory, T.H. White and Camelot 3000.