Eamon Espey is one of the more remarkable, singular cartoonists to come along in the last decade. His first book, Wormdye, was a stunning feat of fever-dream imagery and pitch-black humor. Songs of the Abyss, which likewise collects a number of minicomics he's published over the past few years, is in many ways a more mature and cohesive work. At its heart, this book is about worship. It's about what we choose to worship, why we do so and the implications of this act. The essential point that Espey gets across is that what we choose to worship as a society and a culture has a savage component that is not unlike the way the Aztecs went about their ways: a vast civilization built on blood sacrifice, spectacle, hierarchies, false mysticism and degradation. This isn't about religion vs science either; in Espey's eyes, the choices made through pure rationality and science objectifies life (thus rendering it a subject for sacrifice) every bit as much as religion does.

Espey annotates each of the five chapters in the book, adding clarity to much of his symbolism without resorting to explaining every detail; indeed, some of his annotations are almost as enigmatic as his drawings. The book dips heavily into mythology and creation myths in particular, as events that are both horrible and wonderful. In "The Land That Once Lived", Espey explores Egyptian mythology to tell the story of Atum vomiting up his semen to create his children Tefnut and Shu. Espey's fluid and vibratory line's foundation is built on the simplicity of his character design, which allows him to go crazy using negative space, psychedelic patterns and baroque decorative touches.

The following chapter, "Asbestos Wick", picks up where the prior chapter left off, as the child of Tefnut and Shu, Adam, finds Eve living in a tree. The story of Cain and Abel is played out (as the familiar and bizarre Espey creations Tommy and Marco) as a collection of nightmarish, hallucinatory yet ultimately funny images depicting worship, dismemberment, ritual sex, myths, and rollicking high adventure. The murder of Abel leads directly to civilization, science, exploitation, religion as an institution and other systematic horrors and wonders, until sin is codified into the Seven Deadly Sins, each with an Espey depiction more awesomely horrible than the next. What makes his art so affecting is not just the gruesome nature of the violence, but the way in which he carefully hatches and cross-hatches so many elements of the page, such that the reader is either forced to skip past them or burn them into one's brain if you dare to engage them. There's no such thing as a casual reading of an Espey book; you may as well have not read it at all.

The following chapter, "Asbestos Wick", picks up where the prior chapter left off, as the child of Tefnut and Shu, Adam, finds Eve living in a tree. The story of Cain and Abel is played out (as the familiar and bizarre Espey creations Tommy and Marco) as a collection of nightmarish, hallucinatory yet ultimately funny images depicting worship, dismemberment, ritual sex, myths, and rollicking high adventure. The murder of Abel leads directly to civilization, science, exploitation, religion as an institution and other systematic horrors and wonders, until sin is codified into the Seven Deadly Sins, each with an Espey depiction more awesomely horrible than the next. What makes his art so affecting is not just the gruesome nature of the violence, but the way in which he carefully hatches and cross-hatches so many elements of the page, such that the reader is either forced to skip past them or burn them into one's brain if you dare to engage them. There's no such thing as a casual reading of an Espey book; you may as well have not read it at all.

The third chapter, "Death Deals" is perhaps the most intense of all of Espey’s comics, and that’s saying something. Drawn in his exacting line, this is a loose collection of narrative images weaving in and out of each other depicting murder, mayhem, sexual violation, body horror and other gruesome but deliberately static images. Espey manages the neat trick of flipping between standard panel-to-panel transitions and still drawings that look more like something from a cave painting or stained glass painting. The most disturbing images include a Santa Claus murdering everyone (including pets) in a home after his discovery of a gun as a gift he’s delivering warps his mind, as well as an unflinching ritual sacrifice and violation of a young woman manacled to a tree stump. Incredibly, the events in this story are based on a real life incident: the Covina Massacre.

The third chapter, "Death Deals" is perhaps the most intense of all of Espey’s comics, and that’s saying something. Drawn in his exacting line, this is a loose collection of narrative images weaving in and out of each other depicting murder, mayhem, sexual violation, body horror and other gruesome but deliberately static images. Espey manages the neat trick of flipping between standard panel-to-panel transitions and still drawings that look more like something from a cave painting or stained glass painting. The most disturbing images include a Santa Claus murdering everyone (including pets) in a home after his discovery of a gun as a gift he’s delivering warps his mind, as well as an unflinching ritual sacrifice and violation of a young woman manacled to a tree stump. Incredibly, the events in this story are based on a real life incident: the Covina Massacre.

These are images straight from Espey’s id, reminiscent of the sort of thing that Rory Hayes used to do. His drawings, horrific as they appear, are absolutely exquisitely rendered. Espey’s comics are nightmarishly absurd, drawn with a clarity that forces the reader to confront beauty and ugliness in the same panel. They are genuinely disturbing and thought-provoking in a way that doesn’t feel affected or calculating. Espey is not trying to shock, but rather seeks to get these images out of his head and onto paper. Interestingly, the lone survivor of the attack, a girl, becomes Joan of Arc in this story, negotiating savage city streets before winding up in a horrible afterlife, part of a narrative about humanity's self-destructive qualities.

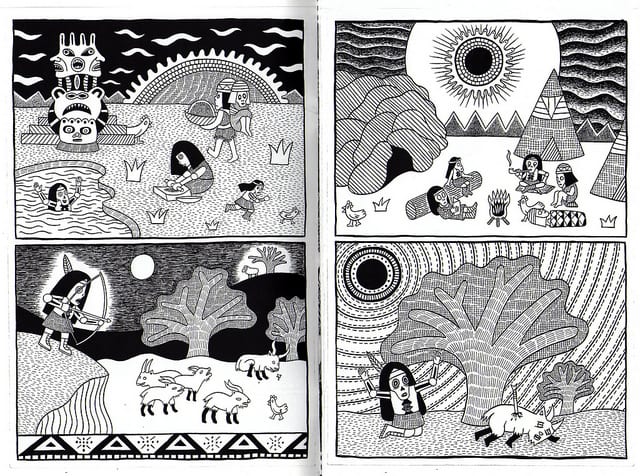

"Ishi's Brain" is another example of how Espey forces the reader to approach the page on his terms, because the denseness and intensity of his drawings keeps one constantly off-balance. This story has a far more straightforward narrative than many of his comics, involving the journey of a skeletonoid man who must leave his village to track down a brain in an UFO that has kidnapped his livestock. Despite the ridiculousness of that plot summary, Espey immediately establishes this world for the reader, introducing the livestock and implying its mystical importance with his intricate, mystical decorative flourishes. The second page introduces us to the book's protagonist, a triumph of design. The smallish skeleton man, like many of Espey's characters, is deceptively cute. With what seems to be a feather stuck in his skull, he goes about the business of providing for his village and living his life, until the day he has to confront the UFO creature. That particular journey does not end well, and along the way he encounters a number of Espey's more familiar characters (like the maniacal twin boys with curly hair) in a kind of fever dream. In the annotations, Espey reveals that the protagonist meets god in a shaman's lodge, allowing the last of his tribe to find the others in a new form.

"Ishi's Brain" is another example of how Espey forces the reader to approach the page on his terms, because the denseness and intensity of his drawings keeps one constantly off-balance. This story has a far more straightforward narrative than many of his comics, involving the journey of a skeletonoid man who must leave his village to track down a brain in an UFO that has kidnapped his livestock. Despite the ridiculousness of that plot summary, Espey immediately establishes this world for the reader, introducing the livestock and implying its mystical importance with his intricate, mystical decorative flourishes. The second page introduces us to the book's protagonist, a triumph of design. The smallish skeleton man, like many of Espey's characters, is deceptively cute. With what seems to be a feather stuck in his skull, he goes about the business of providing for his village and living his life, until the day he has to confront the UFO creature. That particular journey does not end well, and along the way he encounters a number of Espey's more familiar characters (like the maniacal twin boys with curly hair) in a kind of fever dream. In the annotations, Espey reveals that the protagonist meets god in a shaman's lodge, allowing the last of his tribe to find the others in a new form.

The story is based on Ishi, the last Native American to live free of European influence. The parallels that Espey creates with relation to his character's fate and the fate of Native Americans is not surprising. As always, Espey's images revolve around the capricious and vicious nature of everyday life and the ways in which his characters try to negotiate spaces and forces that are completely out of their control, actively predatory and voracious. Even when he's at his most disturbing in terms of violence and sheer madness as he takes his ideas to their logical conclusion, Espey never abandons his sense of humor, style and theme. Interestingly, Espey recently finished a national tour that featured him and his girlfriend, the puppeteer Lisa Krause, doing a puppet performance of this story.

"Black Night In Diablo Crater" is a recapitulation and epilogue for all of the other stories. Joan escapes her fate and transcends reality, as does the repentant scientist. Santa Claus also returns to destroy everything he started and loved and then ends himself, which I take as an end to destructive myths built on consumption. The book ends with the scientist riding into the void. The point of Songs of the Abyss is what implications our actions have in our time on earth, especially in terms of how we worship and what we choose to create in order to fulfill the promise of worship. Not all creation is good, and not all destruction is bad seems to be a major aspect of the book. We must be careful in what we create, because our creations can quickly get out of our control. The abyss awaits us all, Espey points out, and it will lay waste to every institution. He suggests not necessarily that there's a heaven for the just, but that goodness and love are their own forms of transcendence. Even with his annotations, this book is open to all sorts of interpretations, but there's no question that it demands that the reader work to put together the images and follow the nightmare logic that he so expertly crafted.

"Black Night In Diablo Crater" is a recapitulation and epilogue for all of the other stories. Joan escapes her fate and transcends reality, as does the repentant scientist. Santa Claus also returns to destroy everything he started and loved and then ends himself, which I take as an end to destructive myths built on consumption. The book ends with the scientist riding into the void. The point of Songs of the Abyss is what implications our actions have in our time on earth, especially in terms of how we worship and what we choose to create in order to fulfill the promise of worship. Not all creation is good, and not all destruction is bad seems to be a major aspect of the book. We must be careful in what we create, because our creations can quickly get out of our control. The abyss awaits us all, Espey points out, and it will lay waste to every institution. He suggests not necessarily that there's a heaven for the just, but that goodness and love are their own forms of transcendence. Even with his annotations, this book is open to all sorts of interpretations, but there's no question that it demands that the reader work to put together the images and follow the nightmare logic that he so expertly crafted.