What the #@$! are comics, anyway?

The new large, gorgeous tome, Society Is Nix: Gleeful Anarchy at the Dawn of the American Comic Strip 1895-1915 (edited by Peter Maresca and designed by Philippe Ghelmetti), opens a window in time, raising and suggesting answers to that question with a cascading trove of re-discovered comics masterpieces so old they seem new again.

When the roots of a popular art form take on new life, vital new art emerges -- and with smart, elaborate books like Society Is Nix arriving at what may be the height of the current revival of the American newspaper comic strip, we just might be headed for a comics Renaissance. The greatest value of a book like Society Is Nix is that it gives us the work of forgotten cartoonists of the distant past who were so different -- and so good -- that we are shocked into meeting their work in the moment, without any cultural preconceptions.

For example, consider Kate Carew.

Born Mary Williams, she worked as a staff artist at the San Francisco Examiner circa 1890-95. She was the only woman artist working on the paper at that time. In the late 1890s, she escaped an unhappy marriage with a new partner -- a writer named Chambers -- and traveled to New York City where she landed a job as a writer-cartoonist with Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper, the New York World as a writer and cartoonist. Rewind that sentence. Think about it.

A woman. Left her marriage. Traveled to the biggest, most vital city in the world at the time. Got a job on one of the top newspapers in America, run and staffed by men. Cartooned. She did all this around the turn of the century through the early teens. American women got the right to vote in 1920. Got it? Okay, let’s go on -- the story gets even more remarkable.

Mary Williams adopted the name “Kate Carew” and wrote candid, witty interviews with luminaries of the day, including Mark Twain, Pablo Picasso, and the Wright Brothers. She adorned her interviews with her unique “Carewatures,” and often drew herself into the scene. Imagine Oprah Winfrey as a liberated woman caricaturist-interviewer in 1900 and you have an idea of who Kate Carew was. Incidentally, her brother was famed cartoonist Gluyas Williams (their politics and worldviews, as her granddaughter, Christine Chambers, observes, were sometimes quite different).

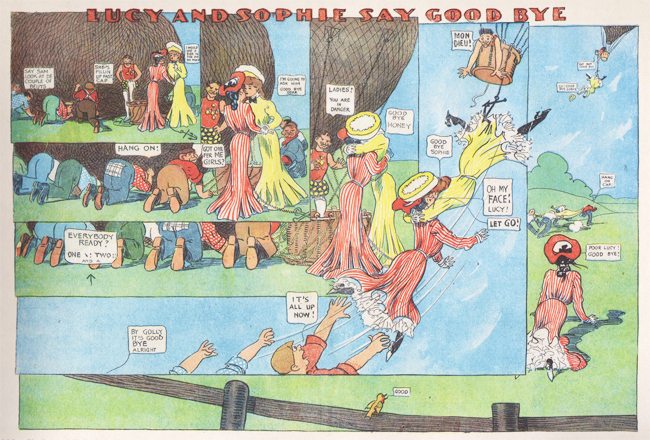

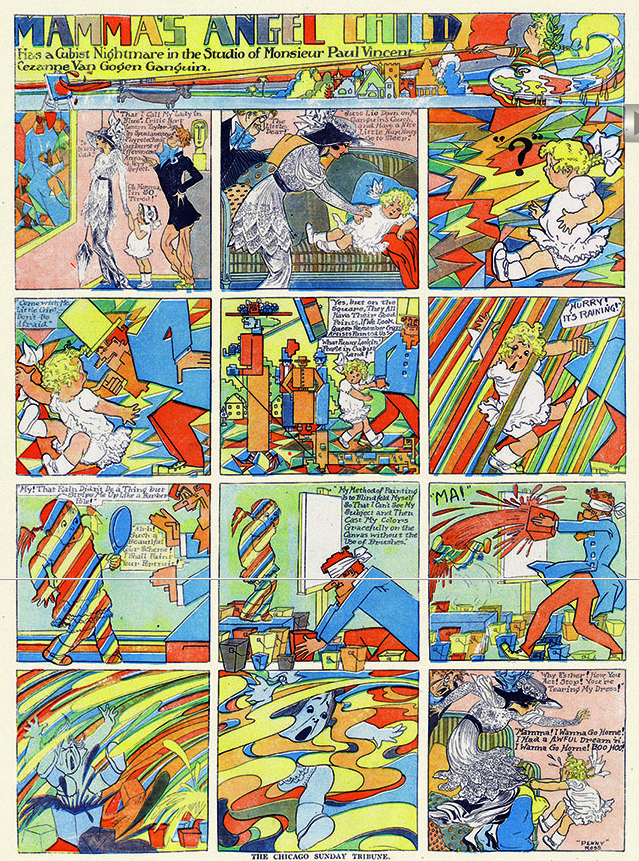

Her comic strip, (one of two known strips by her) the splendidly idiosyncratic The Angel Child, ran in the World’s color Sunday supplement from 1902 to 1905. The Angel Child featured a spirited and independent little New York girl who is a forerunner of the famous Eloise. The strip is drawn in a way that captures children's art without a trace of condescension or irony, although the situations and humor are extremely sophisticated. At a time when the Katezenjammer Kids were fiendishly tying firecrackers to cat's tails, The Angel Child presented a feminine view of mischief. The strip, created by a fiercely independent artist, proclaims that girls have just as much right to be bad as boys. In the example shown in Society Is Nix, two sweet-faced little girls engage in one-upmanship (or, should that be onewomanship?) and eventually wind up on the top of New York's famous Flatiron Building. This one example alone, drawn in a disarmingly simple style, contains themes that touch on women's suffrage, childhood mischief, and the milieu of life in New York City at the turn of the twentieth century. Beyond all of this, the strip also says something about what comics can be -- that they don't merely need to be repetitive commercial products, but instead can offer a highly personalized form of storytelling. I see something of Gabrielle Belle in Kate Carew's work.

There are numerous unearthed gems like Kate Carew's comic in this book. Such as: C.A. Beatty. We don’t know a thing about him, but each panel of his strip Little Denny Mud is a half-tone photograph of a clay frieze. There’s one in Nix.

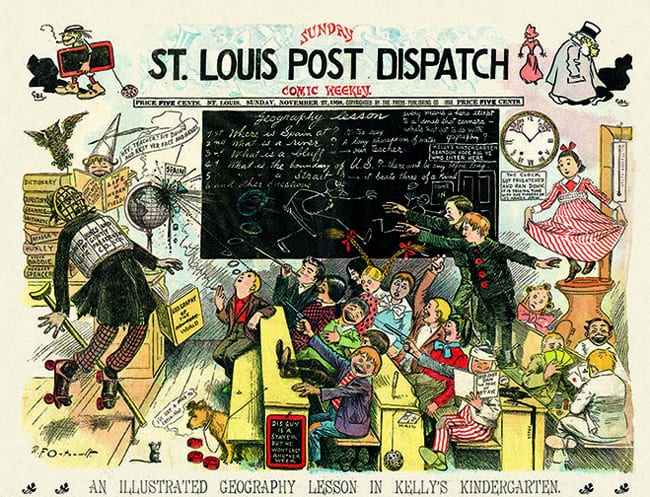

Or Alfred Frueh, the painter who studied in Europe, befriended Matisse and Braque, and drew some elegant Sunday comics – there’s one in Nix, so loose and free that it almost seems like a dream - kinda like John Porcellino's comics:

Then there’s Augustus L. Jansson, a Boston cartoonist who, in 1904, told the story of the American Revolution in Sunday comics -- using playing card style art in op-art patterns that would be more at home on late 1960s rock posters. And yes, there’s a hallucinogenic Jansson page in Nix.

The Old, Weird American Comic Strip

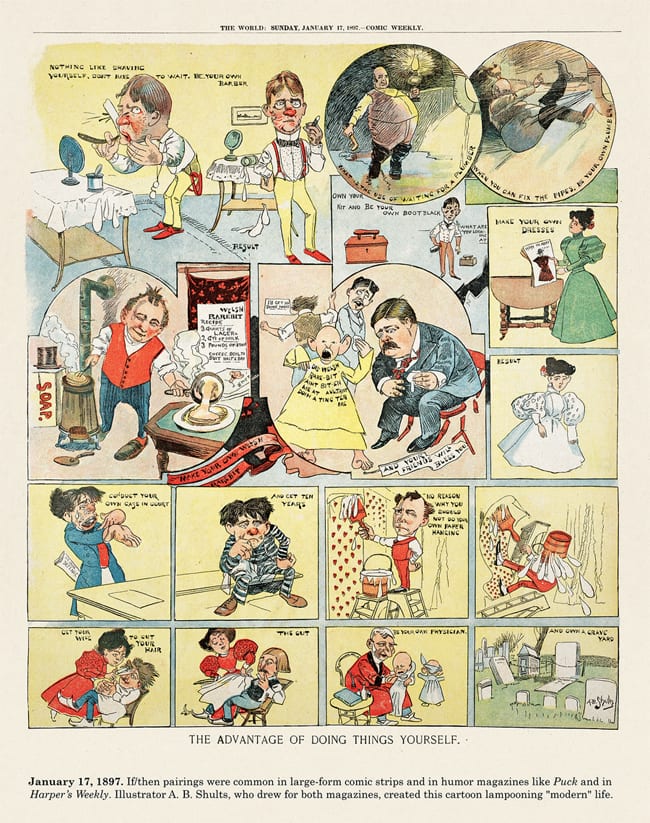

Instead of creating one concept, like say Blondie, and sticking with it for generations -- comics creators working in the years 1895 to 1915 would try out new concepts for mere days or weeks at a time and then move on to the next idea. There was no set formula, and -- judging by the evidence presented in Society Is Nix -- many of the cartoonists working in newspapers at the time were interested in seeing what could be done with this new language.

After reading Society Is Nix, it seems to me that the creative chaos of this era of comics is more spiritually connected to the independent "art" comics of the last 20 years than the staid, repetitious newspaper comic strips that are usually said to be the children of these innovators.

In any case, I wouldn’t know about Kate Carew, Little Denny Mud, the impressionistic comics of Alfred Frueh, or Augustus Jansson -- or dozens of others -- if it weren’t for Society Is Nix. Turning people on to some of the great old and forgotten comics is one of the stated purposes of the book. In December of last year, Nix's publisher and editor, Peter Maresca, wrote me in a letter about his idea for a new Sunday Press collection:

“My next full-size anthology will present the earliest comics – 1895 to 1915. The point of the book will be twofold: First, to present a pastiche of the period, showing comics that have rarely been reprinted, if at all. Second, to draw attention to the myriad of styles and formats that appeared before comics settled into a more standard look in the late teens and 1920s. As for the idea of ‘anarchy’ in the early comics, I’ll repeat this conceit as it is shown in format, content, and even the ‘business’ during the formative years of the comic strip."

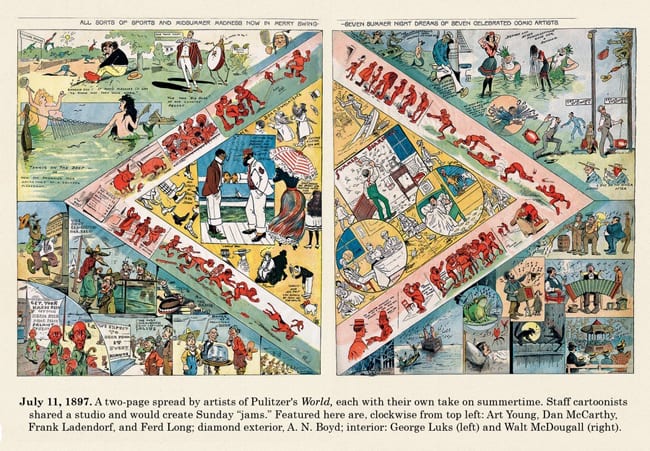

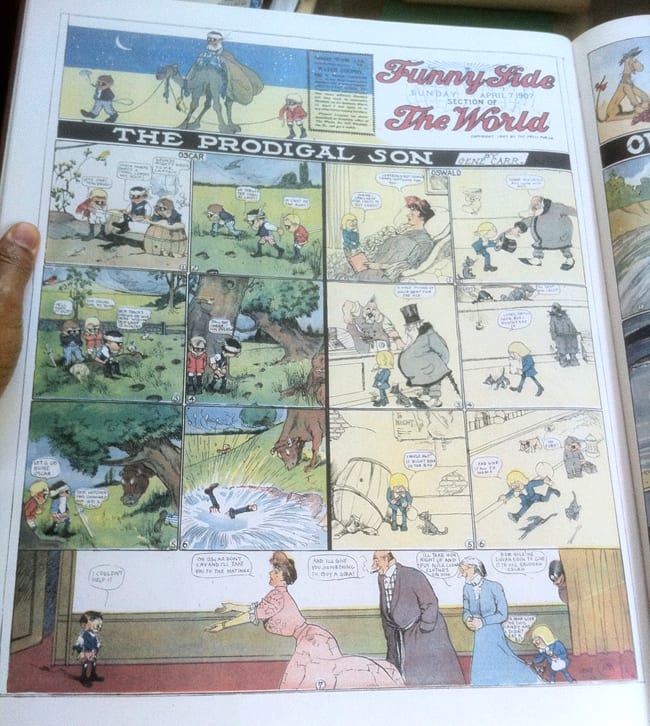

The result, Society Is Nix, succeeds far beyond any expectations it was possible for me to have. There’s a wealth of material here that is long overdue for re-discovery: The spiritual slapstick of James Swinnerton, the well-written character-driven comics of Gene Carr that anticipate where comic strips would go in about 20 years, the cartooning excellence of Raymond Crawford Ewer, the innovative screwballism of Frederick Burr Opper, the crazy, wild jam pages between artists, the stunning spreads, the graphic experimentation -- it's a game-changer of a book.

Chris Ware calls Society Is Nix “a mind-blowing portable museum retrospective of the raw, tangled ferocity and frustration that went into the making of America.” And, by God, he’s right.

Yeah, Yeah – Old Newspaper Comics, Blah Blah

Every damned article I’ve ever read about comics history always has that boring part about hundred-year old American newspaper comics. That stuff has always been dull reading to me because I had very few examples of the old, weird American comic strip to study. And -- the few I had were reproduced in sizes much smaller (and harder to read) than their intended, original formats.

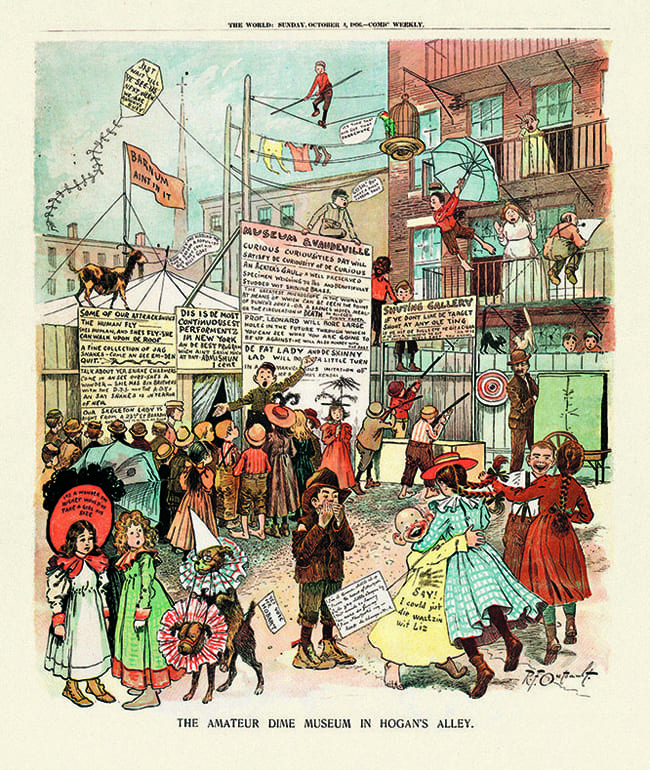

I aim to persuade those of you that think old newspaper comics are dull, irrelevant, and stale -- those of you who are (like me) sick to death of reading about The #@%!ing Yellow Kid and Katzenjammers and that Boring Bastard Buster Brown – I want to show you that old newspaper comics – certain ones (and there’s a LOT of ‘em) – are actually surprisingly vital -- and have a lot to offer a modern reader.

Society Is Nix does include some of those required YellowKidKatzenjammerBusterBrown pages – as well as rare work by George Herriman, Winsor McCay, George McManus, and even a touch of Frank King -- but there’s far, far more comics by people you never heard of that will – when you slow down, and really look – blow your mind. It should be noted that reading the pages of The Yellow Kid, Buster Brown, and the Katzemjammer Kids in Nix is surprisingly rewarding. This is in part because they are pages of high interest, such as surprising jams between two or more artists -- and, in part, because they are properly presented in the correct size and colors.

There’s a book by John Berger called Ways of Seeing. It’s a slim classic that teaches the reader how to look at art on its own terms, not in some pre-conceived critical structure. We need a book like this for looking at old newspaper and magazine comics. They were created in a time before the Internet, before computers, television, and even before radio. The  comics in Society Is Nix come from an era when the idea of color in a newspaper was something new and exciting. Therefore, the sensibility that one meets these dense, rich pages with needs to be different than the mindset we have when we read, say, Dilbert or the latest Batman comic.

comics in Society Is Nix come from an era when the idea of color in a newspaper was something new and exciting. Therefore, the sensibility that one meets these dense, rich pages with needs to be different than the mindset we have when we read, say, Dilbert or the latest Batman comic.

Books like Society Is Nix go a long way towards training our minds to read the older version of the language of sequential narrative. It’s also a way to link with the past. When one guffaws at a hundred-year old comic strip, one feels a certain immutable kinship with people who lived in an earlier time.

Society Is Nix is one of those ground-marking, land-breaking, once-every-decade-or-so books that simultaneously deepens the definition of a form and explodes it like a cannon packed with fireworks on the Fourth of July – the very image on the book’s cover, drawn by the mysterious comics stylist Dink Shannon as part of a wild jam page with several other cartoonists in 1900 (reprinted in the book’s interior).

The cover image perfectly shows the gleeful violence of the early American comic strip, but it also suggests that the book is aiming to explode The Canon of what has been regarded as the great early comics.

Transfixed by Nix

In this review, I’m gonna rave. It’s hard not to, when writing about this book. At least I’m in good company. Art Spiegelman, poetically articulate as usual, said about Society Is Nix: “… never thought anything like this could exist outside my dream life.”

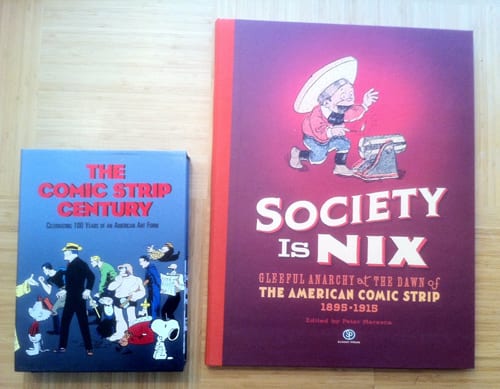

Society Is Nix belongs on the same shelf (although you might have to rebuild the shelf to fit this huge volume) with The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics by Bill Blackbeard, Martin Williams, and John Canaday (Smithsonian Institution Press 1977), The Comic Strip Century: Celebrating 100 Years of An American Art Form by Bill Blackbeard and Dale Crain (Kitchen Sink Press, 1995), and Art Out Time: Unknown Comics Visionaries 1900-1969 by Dan Nadel (Abrams ComicArts, 2006). In many ways, Nix is the next evolutionary step forward from the accomplishments of these collections.

As far as I know, Nix is the first top-drawer collection to focus exclusively on the first twenty years of American Newspaper comics, as well as being the first book to reprint the work of many of the cartoonists represented therein.

I regard Society Is Nix to be a big, important book.

Big. (Size matters – at least in reprinting comics)

It's big.

The presentation of notable work by not just one, but dozens of "lost" cartoonists is a big deal. But the book itself -- like all of the Sunday Press volumes -- is big in size, and that is worth considering.

At 21 inches in height and 16 inches in width, and almost ten pounds in weight, this book is a monolith. Word of advice: if you read it in bed, make sure you don’t doze off holding it – if your hands relax and the book falls, you may suffer a broken nose, or a concussion.

Sunday Press aims to present the best art of the early American Sunday newspaper comics in their original size. Turns out that “original size” is freakin’ huge. As printed newspapers in the early years of the 21st century reduce their page dimensions drastically it is easy to forget that hundred-year-old newspapers – and the comics in them – were published in surprisingly large dimensions.

Publisher-editor Peter Maresca and designer Philippe Ghelmetti have lovingly restored and reprinted giant early comics for several impressive previous collections in the Sunday Press series.

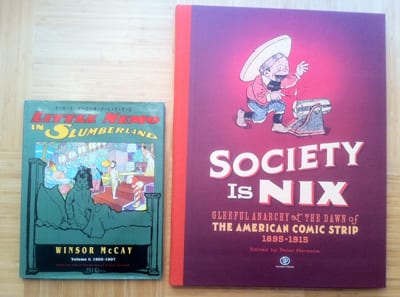

There’s two volumes of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo pages that take my breath away.

There’s a massive tome of Frank King’s Gasoline Alley pages that steals my heart every time I dip into it. The beauty of King’s art as we see in full-size, full color Sundays exquisitely reflects the tender human connection between a father and his son as they both age. (I was fascinated to discover in Nix a 1904 example of F. M. Follet's The Kid, which is an artistic antecedent to the King Gasoline Alley Sundays)

Sunday press has given us collections of George Herriman’s Sunday Krazy Kat pages (reading them in the original size is a revelation) and more obscure but no less important books on Gustave Verbeek, Winsor McCay’s Little Sammy Sneeze (this one comes with a bonus cartoon decorated tissue box cover), and Walt McDougall’s bizarre Oz comics, written by the series creator Frank Baum (in which the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman, Cowardly Lion and like company leave the land of Oz and explore early 20th century America!).

Seeing both familiar work (McCay, Herriman, and King) and more obscure work in the actual size it was designed for turns out to be critically important to understanding the comics themselves. Previous landmark collections of great old newspaper comics, such as The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics and The Comic Strip Century present the art in greatly reduced form, less than half of its original size. Subsequent books, like Richard Marschall's Complete Little Nemo In Slumberland series seemed luxuriantly large at the time (the series remains a favorite on my bookshelf), but actually continued to offer reduced images.

Why such a big deal about size, you ask. Well, you know what they say about comics collectors who have really large books

Aside from that, the big deal is the meaning that arises from art presented in its proper context.

Aside from that, the big deal is the meaning that arises from art presented in its proper context.

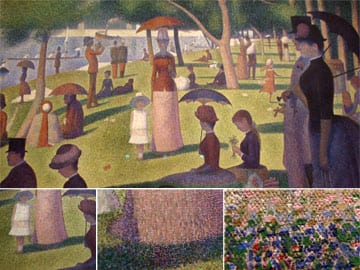

Imagine looking a postcard of the landmark French Impressionist painting by Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon On The Island of La Grand Jatte (1884-1886). The actual painting size is about six-and-half feet tall and ten feet wide. The painting is the size of a wall. It had to be this big, which is something you realize when you see it in person, or reproduced in something larger than a postcard. It’s made of thousands of tiny dots of paint. When you start walking back from it, the image begins to form. The painting shows us how television screens and color pixels work -- decades before they were invented. All the daring brilliance of this approach is lost if we just look at a postcard-sized, or a standard art book reproduction of the painting.

Or, how about this: silent films. Similar to old newspaper comics, the old Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin comedies were once presented to us in an altered state that radically changed and obscured our ability to experience the art as it was designed to be experienced. For decades, we viewed these films using machines that sped them up. After awhile, it was a cultural truism that old comedies were jerky and moved in an oddly sped up fashion. About 15 years ago, companies like Kino began to use computer technology to restore these early silent films to their correct projection speeds and suddenly – suddenly – we understood. Chaplin’s subtle, masterful eyebrow lifts and shrugs – Keaton’s brilliant body language – it all suddenly spoke volumes when shown in the way originally designed. The films became alive again.

When we read a 1902 Sunday newspaper comic page in its intended size and color, it’s as if we are standing in front of Seurat’s wall-sized masterpiece, or seeing Chaplin and Keaton for the first time. In Forgotten Fantasies, the jaw-dropping Sunday Press book published a couple of years ago that presents an assortment of early American newspaper comics with fantasy themes, there is a complete run of Charles Forbell’s Naughty Pete comics – extraordinary explorations of the way comics can play with time and space, and an influence on Chris Ware. One of our most astute and articulate comics historians, Art Spiegelman, observed that the smaller reproduction of Naughty Pete found in the 1977 Smithsonian Collection didn’t impress him. It wasn’t until he read the page in the size it was originally designed for in Sunday Press’ Forgotten Fantasy (2012) that Spiegelman “got it."

That’s why the size, and the masterful restoration and reproduction of the art in Society Is Nix is such a big deal. It makes it possible to finally “get” these weird, old comics.

Like I said, this is a big, important book.

Important.

There has never been a book quite this before – and this difference, in addition to the book's actual size, is huge.

Sunday Press' Forgotten Fantasy (2011) presents an assortment of gorgeous, accomplished early newspaper comics organized around a theme: fantasy. The collection is organized around large chunks of material. We get a chunk that is the complete comics of the magnificent Lyonel Feininger. We get all the Naughty Petes and all the Explorigators. The book ends with a chunk of the color Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend by Winsor McCay. There are a few tantalizing bits and pieces in the cracks between these cornerstones, like an example of Thornton Fisher’s wonderful strip The Wishing Wisp.

Society Is Nix takes another bold step in the evolution of this type of book, presenting selected examples from a 20-year period, 1895 to 1915. They are mostly in chronological sequence and represent a vast assortment of artists, styles, and approaches. In his introductory essay, Maresca states his intention to create “a time machine of a Sunday supplement, a mash-up giving lovers of comics, popular culture, and history an opportunity to experience these incredible pages as if they were appearing in one giant, twenty-year long newspaper, with none of the disturbing news.”

I dunno about that last statement – I think I know what Peter was getting at, but there’s plenty to be found in these comics that seem like disturbing news to me – these comics put us face-to-face with social and political issues that are still very much alive for us today – issues that arise from the experiment in democracy represented by the United States – racism, equality, distribution of resources, the assimilation (or rejection) of other cultures, and so on.

I dunno about that last statement – I think I know what Peter was getting at, but there’s plenty to be found in these comics that seem like disturbing news to me – these comics put us face-to-face with social and political issues that are still very much alive for us today – issues that arise from the experiment in democracy represented by the United States – racism, equality, distribution of resources, the assimilation (or rejection) of other cultures, and so on.

It’s no accident that the book’s subtitle contains the word “anarchy.” Society Is Nix (the book's title, by the way, is lifted from a Katzenjammer Kids comics in which an adult laments: "Mit dose kids, society is nix.") shows us the turbulent times of the early 20th century, and also the wonderful wild and unrestrained lunges at different ways to present comics.

Reading this book is like tumbling down the spiral staircase inside the Statue of Liberty – a fun, wild, violent way to experience the best of America. At the bottom of the stairs, with stars swirling around our head, eyes opened wide, we think:

What the hell are comics, anyway?

Jostling our minds and eliciting that core question is an important accomplishment. Here’s what I thought I knew about comics: Comics are sequential narratives that use a mixture of words and images. Other ideas about comics flipping through my mind include:

- Stuff printed on cheap paper meant to be read for fun

- An intensely personal form of expression

- A commodity

- A form of storytelling

- Graphical representations mimicking musical compositions

- The wellspring of multi-million dollar grossing hit movies of the early twenty-first century

- Low culture (some say)

- One of the underappreciated foundations of some high culture (others say)

Society Is Nix helps us to see a few more of the defining aspects of comics, including: great art we forgot about, a collaborative art form, and the fact that this is often an art form made from a deep and transcendent commitment that borders on madness.

Comics are great art we forgot about. Okay. Not all comics from 1895-1915 are great. But a lot more than you’d ever think. Every page in Nix offers something great.

Comics are often a collaborative art. The integrity of the presentation of art in Society Is Nix allows us to see, perhaps like never before, how instrumental the anonymous colorists and printing technicians were in the development of this form.

The big cheese, Richard F. Outcault says it himself, in an 1898 essay reprinted in full in Nix (one of two fascinating early historical essays in the book -- which sit well alongside the nine original essays by Peter Maresca, Thierry Smoldern, Richard Samuel West, R.C. Harvey, Brian Walker, Alfredo Castelli, Bill Kartalopoulos, David Gerstein, and me). In "How The Yellow Kid Was Born," Outcault says "I didn't invent the Yellow Kid." he explains that it was a colorist at the paper that decided to make the kid's slip a bright yellow - making a hit, history, and leading to the term, "yellow journalism."

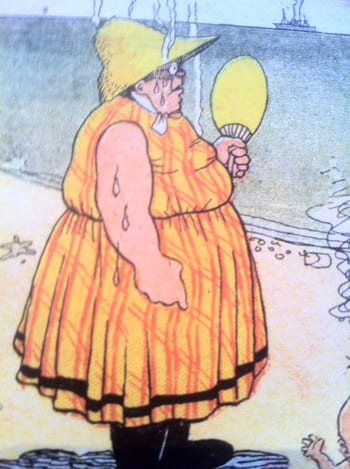

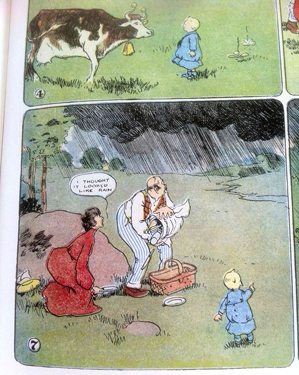

Because Nix finally allows us to see these old comics clearly, we can become more appreciative of the contributions of the early pressmen. In a terrific one-shot page from Jimmy Swinnerton, comically depicting the four seasons in New York, we can see the colorist is an unknown collaborator in the success of the comic. In the panel showing Summer, the colorist has artfully drawn an overlay of orange lines that both decorate the stout woman's dress, and express the wilting effect of the heat:

In the panel showing Fall, the colorist has again taken to the time meticulously add a decorative pattern to the stout woman's dress (and, additionally, her stockings). This time, the pattern helps to express the frenetic energy of the winds blowing through the city streets:

In Winter, the colorist again uses pattern to show the stillness and solemnity of the season:

What really knocks me out, as if the great cartooning and coloring weren't enuff, is that in the Spring panel, the colorist has used an extremely light touch, allowing the whiteness of the paper to work as the "color" of rain:

Comics at their best are made by gifted and passionate people. Society Is Nix includes mini-biographies of 64 of the artists whose works are represented in the retrospective (I wrote about three-fourths of those, earning a "contributing editor" credit). There's also a wealth of information worked into the captions. Reading this materials helps us to see that the early American newspaper comics emanate mostly from people living ever-accelerating lives in teeming urban environments. We realize the work was created with short deadlines to feed the ravenous maw of the public’s growing appetite for printed entertainment.

While the pay in many cases was decent for newspaper cartoonists of this era, there can be no doubt that most – if not all – of the work contained in Society Is Nix represents a high level of passion and love for comics that transcends the need to earn a living. These people must have worked day and night to produce some of this work, which was consumed in a day by millions who eagerly looked for more the next day. The pressure must have been enormous.

Such as Gus Dirks – the younger brother of Rudolph Dirks, who created The Katzenjammer Kids, and who is represented in several places in Society Is Nix. A gifted artist and satirist, Gus established himself with his own take on the “bug world” cartoons then in vogue. These cartoons are filled with exacting line work and baroque detailing. More than good drawing, Gus could draw funny and weird. When I first looked at his work, I thought of Robert Crumb and B. Kliban.

In 1902, Gus Dirks took his own life at approximately age 21. A June 12, 1902 New York World article suggested his suicide was due, in part, to the stress of his cartooning career: “Gus Dirks’ bug pictures made him, supported him, and perhaps killed him.”

The early funnies were created by enormously gifted and restless people who took huge risks, worked furiously hard, and sometimes broke under the strain. In Society Is Nix, there’s bold, satirical work by J. Campbell Cory, a man’s man adventurer who built and flew “aeroplanes,” hunted big game, and prospected for gold out west.

There’s William F. Marriner, who developed an appealing rounded character design that one of his assistants – Pat Sullivan – used to create Felix the Cat. Marriner apparently burned to death when he set own house on fire in a jealous rage at his wife.

There’s William F. Marriner, who developed an appealing rounded character design that one of his assistants – Pat Sullivan – used to create Felix the Cat. Marriner apparently burned to death when he set own house on fire in a jealous rage at his wife.

Most of these early creators only worked in comics a short while, moving on to develop other artistic careers, or to retire in the country as farmers, such as Walt McDougall (who eventually took his own life at age 80, when he was penniless and in poor health). A very few, such as Rube Goldberg (who has two rare Sunday strips in Society Is Nix) maintained an even keel in their lives and were happily productive and stable for decades – but these were the exceptions.

What these founders of the funnies left behind was a legacy of art that was designed to entertain, but contains within it encoded information about the times, about human nature, and about America. In addition to all that, they were working in a new art form and created comics so brilliantly innovative that they rival the best work of today's comics artists (many of whom are students of the old, weird comics). Until recently, much of this legacy was unknown to the general public. The myriad books and articles on comics history published in the last fifty years have, as Society Is Nix reveals, only scratched the surface.

I don’t know how Peter Maresca did it.

He figured out how to reproduce ancient, fragile comics in their original size and colors in a way that makes them once again vital to our culture. His selection is smart and informed. He gets solid writers and historians to write essays that help us to understand and appreciate the art he’s presenting. He figured out how to assemble the broadsheet-sized material into sturdy, well-designed books that are beautiful objects in themselves (although I wish they would print the book names on the spines).

I’m glad as hell that people like Peter Maresca and Philippe Ghelmetti have the talent and crazy passion (perhaps it's a cultural transmission from the original creators) to direct this sweet, strenuous whirlwind of breathtaking forgotten art back into our current world.

Chris Ware has referred to the 1977 Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics as his "Bible," and there's no doubt from reading his various acknowledgements that the book had a profound impact on his development. Part of the value in studying old comics is the expansion of our current thoughts about what can be done in the medium. To intentionally discover the great, little-known comics from 100 years ago results in broadening our minds and deepening our appreciation of the form itself. I'm looking forward to seeing the cultural disruptions that will come from the massive infusion of comics genius given to us in Society Is Nix.

Additional Notes

For more information on Society Is Nix and other Sunday Press Books, go here.

Pages from Society Is Nix, as well as "outtakes" from the book are being serialized at GoComics here.

Another magnificent and important book that presents important early American newspaper comics in their original dimensions is Ulrich Merkl's The Complete Dream of the Rarebit Fiend (1904-1913). You can read a rave review of that volume by scholar Huib van Opstal here.

If you'd like to know more about Kate Carew and a documentary being made about her life and work, go here.

More of Jimmy Swinnerton's great SAM and His Laugh comics.