Living in Baltimore for the past eleven years, my daily life frequently led me to stumble into moments where the landscape felt post-apocalyptic. In the strictest sense, this term is inaccurate; historically our current moment is, at worst, a “pre-apocalyptic” one. While perhaps if I lived in New York City or Washington DC I would be seeing the movements of power that lead to our demise, what you see elsewhere in America are glimpses of a world where society seems to exist only as vestigial traces. “Post-industrial” is the accurate sociological term that describes cities like these, though “post-modern” works about as well, if each momentary image encountered is considered as a discrete work of art. We’re past the point where describing a comic strip as “post-modern” seems a novel form of praise, of course, so it might be better to say that the vaguely post-apocalyptic setting of Drew Lerman’s Snake Creek feels distinctly appropriate for this exact moment.

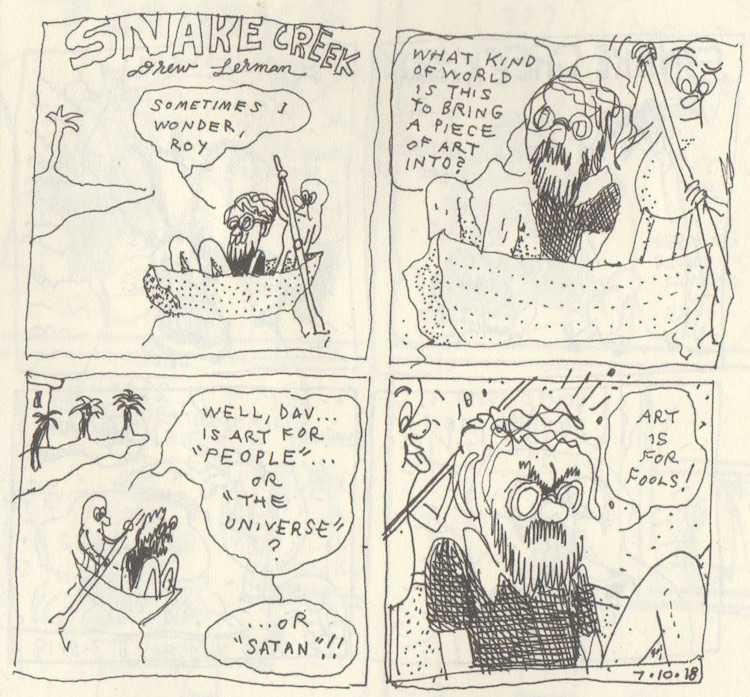

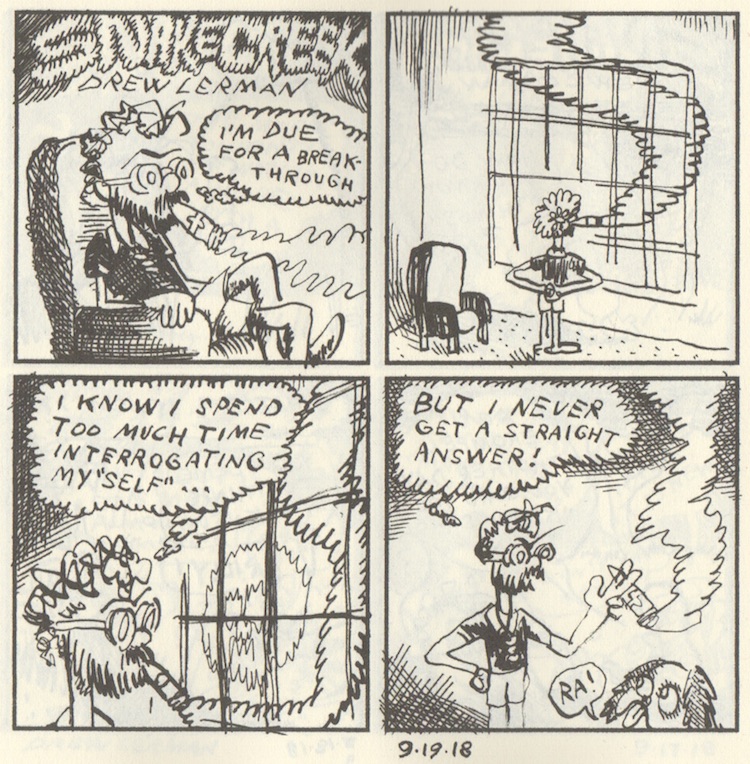

The wasteland the strip occupies is not a place of detailed fantasy world-building, but a barren plain of sand. Think of a Beckett play, but one performed on the borscht belt circuit. The humor of the strip is a philosophical vaudeville where our two main characters, Dav and Roy, search for meaning in a world given over to anarchy. Dav is a man of high-minded and neurotic concerns, who is trying not to refer to his dog as “dug” because he "didn't want to expose him to the curse of naming." His companion Roy is a little freer by virtue of being a little dumber. He sometimes seems like Dav’s child but the relationship between them, like much of the particulars of the larger world, is pretty vague. Dav’s name is presumably Dave, but we only ever read it as spoken through Roy’s baby voice. “Friendship” should suffice to describe their dynamic.

These are not the only characters, and the scribbly, gestural quality of the art that imbues the strip with a feeling of broad humor goes into enough detail to render some of the supporting cast as grotesques. These figures are property owners, or the town’s mayor, figures whose role indicates some semblance of order, though perhaps they stand on ceremony. Plenty of comic strips distinguish themselves through setting. Tumbleweeds takes place in the wild west, B.C. in caveman times, Hagar The Horrible in the Viking era, The Wizard Of Id in the Middle Ages, etc. Such historical settings are a feint that don’t really hold up to any scrutiny, as each cartoonist is willing to embrace anachronism for the sake of a gag, or, in the case of B.C., Christian proselytizing. The vagueness of Snake Creek’s world both falls within this tradition and seems like part of its point. The setting is “neither here nor there,” both in terms of importance and a determined indistinction being the best place to discuss the subject matter of man’s search for meaning. It never feels like a contemplation of a potential future but rather, in keeping with daily comic strip tradition, seems to occupy an absolute present.

Because our particular present is one where people need to seek out meaning without remunerative reward, you will not see Snake Creek syndicated in our nation’s newspapers. Lerman publishes it on social media. What I’m reviewing now is a collection of the first year’s worth of strips, which were produced at pretty close to a daily schedule, though some days were skipped. There’s an inconsistency in how casual or labored-over any strip might be, and some seem executed with different materials, though even the more-composed strips are executed with a sketchiness of cartooned expression that seems to prize the accomplishment of completing a task for the sake of maintaining a practice over the end goal of a well-wrought final product.

Lerman is a cartoonist, like Matthew Thurber, who operates in a lineage of the history of American humor cartooning transforming into literary cartooning by engaging the parallel history of humor in twentieth-century literature. Looking at these strips, you’re looking at something that recalls George Herriman, Harvey Kurtzman, Robert Crumb, Daniel Clowes, Matt Groening, but also thinking: What if Stanley Elkin drew a comic strip? There’s a sense of ethnic comedy that manifests both in the accented-dialect speech that you see in Walt Kelly’s Pogo, and the specifically Jewish humor that comes from a character’s over-educated paralysis, which would be at home in a Joseph Heller novel. The casual approach to drawing allows Lerman to make a burlesque of such neuroses rather than becoming consumed by them. The artist lives in Miami Beach, which Snake Creek’s backgrounds of palm trees and bodies of water, and incidents of stormy weather, seem to be based on. The characters break into abandoned homes, much like those Joy Williams’ Florida-set novel Breaking And Entering.

This is not to suggest it’s a literary masterwork. Its register reminds me of distinctly also-ran comic strips of my youth, like Bud Grace’s Ernie or Jim Meddick’s Robotman, to name two examples I had to Google the creators of. These artists were contemporaries or Gary Larson or Bill Watterson, less fondly remembered now, but still read at the time due to their placement on a comics page in an era where that was still a place to be. The occasional profanity does not make me think of Snake Creek in the context of strips that ran in alt-weeklies, but rather I imagine a daily newspaper where the humor kept pace with the sort of comedy viewable on basic cable, rather than declining into irrelevance. The strip is a niche proposition, not for everyone. I find it charming, though the sense of playfulness it embodies denies the rigor of hard punchlines. Its ambling pace works best when a few days are dedicated to a continuous plot. The virtues of a daily comic strip, or a friend’s social media feed, are the companionship it provides over a period of time. In a post-meaning world, that’s about all you can want.