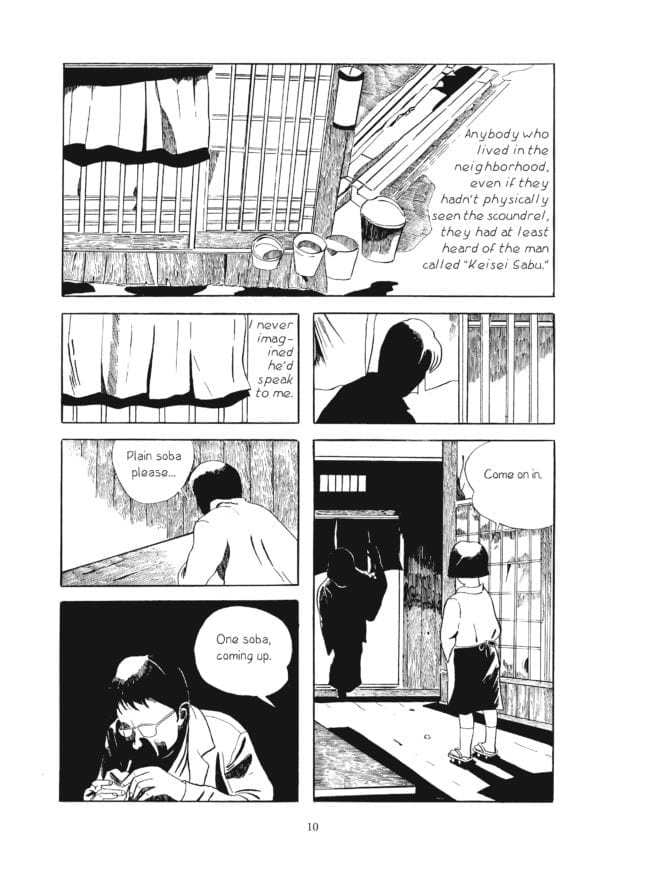

Shaded faces are a fixture of Tadao Tsuge’s Slum Wolf. From the collection’s opening piece, “Sentimental Melody”, and throughout the book, figures come into view with their features obscured. “Melody” begins with a man visiting a sex worker; Tadao shows him in near-silhouette several times before revealing the man’s face. In the story that follows, “The Flight of Ryokichi Aogishi”, Tadao at first renders a man’s head in spot blacks, despite drawing the man's overcoat and the space around him in fine detail. He continues this approach in several of the book’s other stories, encouraging readers to understand his characters in terms of a figurative (and sometimes literal) facelessness. With some artists, an obscured face—and the repetition of that motif across stories and years—might connote a character’s universal experiences. With Tadao's pieces in Slum Wolf, that’s not exactly the case.

The book is translator Ryan Holmberg’s second compilation of Tadao’s work, after Trash Market in 2015. The comics in both volumes reveal similar concerns, though Slum Wolf is an even more affecting, cohesive set of stories. Tadao’s cartooning first appeared in manga periodicals such as Garo and Yagyō, with Wolf collecting select pieces from the late '60s and '70s. Tadao’s subjects in these stories are fairly specific: men who fought for Japan during World War II and/or men who found themselves left behind after Japan’s post-war economic recovery, as well as where these men find themselves a few decades onward.

The spaces these stories explore aren’t always exclusively male, but the stories’ lead characters tend to be. And the men’s discarding of or failure to fulfill the roles and responsibilities of their era often provide the stories’ subtext. They are the type of people Tadao would have seen daily, growing up in a Tokyo red-light district amidst post-war poverty. So why—with such familiar subjects—the shadowy faces?

One answer: they’re a measure of what value the society in which these characters live places on individual lives. (Marginal.) But Tadao’s stories suggest additional understandings, too. Slum Wolf follows people who are both a part of a community and not. Although many of these men have a shared history and live in close proximity, they also live as strangers to each other. And in some pieces, the substance of the story is the measure of how much this condition changes.

After the opening scenes of “Sentimental Melody”, the comic finds its john seated next to another man at a noodle place. They begin sharing stories of Sabu, a local tough and kamikaze trainee who survived the war. The conversation leads to the older man, the john, remarking that, “After the war was over... We were all still hurting. None of our wounds had healed yet.” A reader may suspect that Tadao is depicting a breakthrough between the pair, but Tadao quickly subverts this impression, as the younger of the two declines the chance to pay for the both of them: “Tonight’s the first night I’ve met this man.”

A later story also takes an eatery as the site of a potential communion between strangers. In “Wandering Wolf”, a vagrant enters a new town and begins frequenting a local bar. Across a series of tentative conversations, an understated intimacy begins to develop between the wanderer and the barkeep, one of the book’s more visible female characters. Meanwhile, a gang of locals attempts to bait the man during his stay in town. The vagrant resists until the men begin to harass the barkeep as well, at which point he beats them until they’re down and bleeding in the snow. It’s a burst of violence in defense of the woman’s honor, or perhaps a burst of violence under the pretense of defending her honor. The story casts doubt on the usefulness of spoken language or the language of violence in remedying the wanderer’s remote way of life. Even Tadao’s drifters are stuck.

In Slum Wolf, violence is not an inevitable outcome of characters’ navigations of each other, but it is a common one. “Legend of the Wolf”, the story that follows “Wandering Wolf”, puts two men under the same awning as they wait for a storm to pass. They meet as strangers, only for the younger of the pair—a criminal on the run—to realize that the other one is “Kamikaze Sabu,” a brawler he admired in his youth. (Present here as a different iteration of the Sabu from “Sentimental Melody”—Tadao uses characters in a somewhat repertory fashion.) Nostalgia and admiration flood through the young man, but he’s also compelled to test Sabu’s mettle, with another ambivalent ending as the result.

“Legend of the Wolf” begins with a rendering of the shack under which the two men meet, foreboding and impeccably drawn. Other stories also showcase Tadao’s facility with buildings and landscapes, especially the book’s centerpiece, “Vagabond Plain”. This comic depicts a kind of piecemeal post-war commune, one that hosts drifters, con men, and other lost souls. Its inhabitants live in makeshift huts on a grassy plain that was once a military site, bombed and destroyed by US pilots. Tadao attends to the grasses and clouds of the plain, as well as its remaining traces of wartime infrastructure, with abundant hatching and attention to detail, creating an environment of brutal decline and unkind skies.

Tadao’s work depends on an unblinking matter-of-factness, and so it wouldn’t be right to say his landscapes offer a look at the sublime. Yet they do exist apart, in some respects, from the lives of his characters. One respect is quite literal: like many other manga practitioners, he affects a level of heightened realism in his backgrounds. And so characterizing this approach as unique to Tadao’s work wouldn’t be right either. But the approach does create a fearsome tension in these pieces. The landscapes of “Vagabond Plain” register as indifferent at best, hostile at worst, and all the more so in comparison to Tadao’s figures, which he renders in spare but loose-looking linework. Although his characters are sometimes lively people—and particularly in “Vagabond Plain”, some of them appear at home in squalor—this is not due to the stories’ antagonistic spaces.

Despite its title, “The Death of Ryokichi Aogishi”, Slum Wolf’s closing piece, may be the book’s most optimistic entry. Spotlighting the eccentric residents of a dilapidated boarding house, it at least features a largely functional community. But even this story does not ignore the gravity of its title character’s suicide—and in places, it includes some of Tadao’s most intense landscapes as well. Meeting these comics on their own terms means hoping for little and observing as much as one can. Tadao himself operates in the same manner. Attentiveness its own reward, in a life that may offer few of them, and the result is a collection of complex, enduring works.