What comes to mind when you hear the name Alfred Hitchcock? A scene from one of his many acclaimed films, perhaps? Or maybe the theme song to his television show? My suspicion is that somewhere in that nanosecond or two you instead envisioned a picture of the man himself: rotund, balding, jowly, his nonplussed visage faintly suggesting a wry puckishness that could descend upon you when you least expected it.

That’s because more than any other film director (famed actor-directors like Charlie Chaplin offering the only notable exceptions), Alfred Hitchcock cultivated a public persona that rivaled the popularity of his films. There are many directors who could be described as "colorful characters." There are many directors who are well-known to the public. Few, however, have reached the sort of iconic status where we see a few curved lines joined together and recognize it as his silhouette.

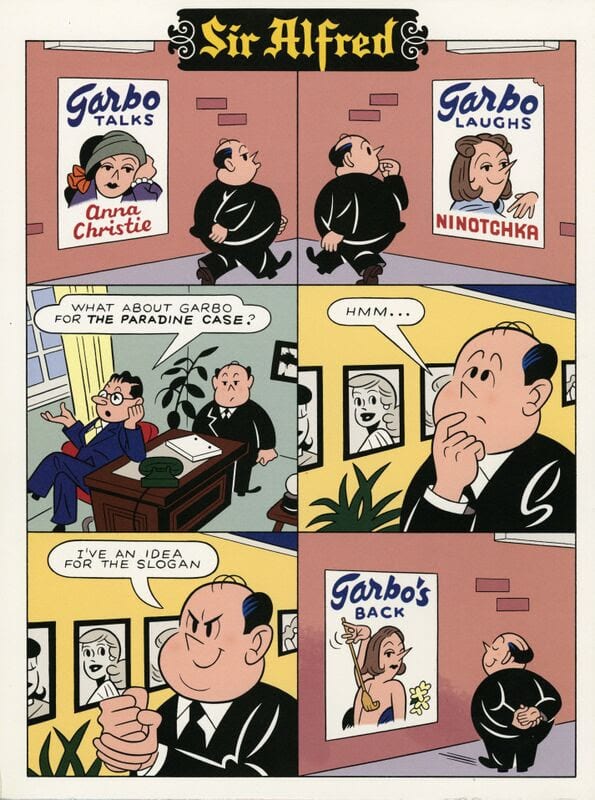

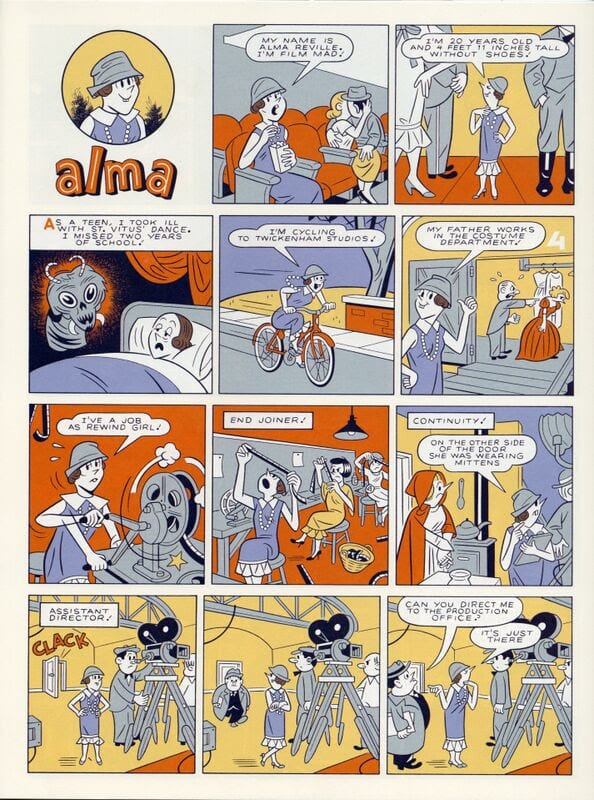

It’s the very public caricature that Tim Hensley exploits so beautifully in Sir Alfred No. 3, the final offering from the seemingly defunct Pigeon Press, now distributed via Fantagraphics.

With its above-average size and slapstick gag format, Sir Alfred evokes both the movie magazines and the humor-based comic books of mid-20th century America, especially titles that drew on established celebrities, like The Adventures of Bob Hope. Even the title is a sly wink to periodicals past, a teasing suggestion of an ongoing Hitchcock series, though, of course, no first or second issue exists.

Hensley’s biggest aesthetic influence here, though, is John Stanley, with Hitchcock drawn to resemble a middle-aged Tubby. It works better than you would imagine -- there always was a cartoonish aspect to Hitchcock’s public persona, right down to the anecdote (shared in the comic) that he wore identical basic black suits for most of his career.

Along the way, however, Hensley takes a moment or two to ape cartoonists such as Robert Ripley, Milt Gross, Don Martin, and Jaime Hernandez. Hensley has proven himself to be a formidable mimic, and perhaps most impressively, he uses this talent not to show off as much as to underscore the comic’s theme (or service the gag at hand).

Hensley is upfront about his intentions with Sir Alfred from the get-go, though as always in his own inimitable, off-kilter style. In an early, full-page sequence, designed to mimic the television show Alfred Hitchcock Presents, “Hitch” addresses the reader, dismissing “graphic novels” while at the same time acknowledging their influence, however minor, on his work. As he talks, Bob Hope enters the room and unpacks a trombone to play a single note that, inevitably, knocks Hitchcock back onto the floor. By acknowledging his influences in so loud and blatant a manner, Hensley reveals both the benefits and (at least cultural) drawbacks of working in such a compressed and cartoonish fashion, especially when delving into biography. It’s a tension that suffuses the whole work.

Rather than proffer a straightforward biography then, Sir Alfred instead serves up a collection of vivid anecdotes about the master of suspense, some apocryphal, some flattering, some humorous, several decidedly none of the above. It’s all presented here in the same gag/slapstick format, though, with Hensley working in a pratfall -- literally or figuratively -- whenever he can.

Many of the stories are funny and show Hitchcock as a spirited practical joker or bon vivant, always at the ready with an amusing quip or putdown. Other sequences convey a tyrannical, egocentric and mean-spirited bully whose anxiety and insecurity over women and sex in general leads him to some ugly moments (particularly with regards to Tippi Hendren).

Just as often, the Hitchcock that arises out of Sir Alfred is a sad, alcoholic, and desperately lonely figure, one whose confidence and slyness hide a deep insecurity. The final sequence, narrated by French director Francois Truffaut, presents a Hitchcock fearful of death and too drunk to make much sense about it.

Along the way, Hensley fills the corners with small details and jokes -- Family Circus characters here, a newsstand of British magazines with names like Dosh and Snog over there. Hensley’s images often lend a sly commentary to the dialogue well. In one sequence, for example David Selznick berates Hitchcock for not taking a master shot. The final panel is a birds-eye-view that both evokes a famous scene from Notorious and perhaps suggests one of the "extra angle" shots Selznick is raving about. As short a comic as this is, it rewards multiple readings.

How do you retell a person’s life? Especially when you have a limited amount of space or time (as we all have in the physical world)? Do you focus primarily on the funny anecdotes? The ugly ones? Both? Is there some sort of balance that can somehow create a fuller picture of a person than anything else? What if you’re doing it in a style that relies upon caricature and simplification? Does it matter since all people will remember are the broad strokes? Sir Alfred ends with a literal shrug of the shoulders, possibly because Hensley isn’t as much interested in answering these questions as he is raising them. What he has built in the process of asking, however, is an entertaining, smart and challenging look at not just a noted artist’s life, but where the boundaries of his chosen medium and artistic style lie, and the capabilities of the biographical genre in general. Yes, it’s that good.