Armed only with a bachelor's degree in English literature and a propensity for shoplifting, a disillusioned copywriter navigates big-city loneliness in the handsome debut graphic novel from Toronto illustrator Michael Cho. Were it not for the small thrill that she finds in nicking magazines from her corner store, Shoplifter's Corrina Park would otherwise crack from the ethical quandary and dull pangs of boredom she fields at the ad agency where she works. She's frustrated that her studies of "Faulkner, Fitzgerald, and Forster" yielded such a compromised career path, and hollow editorial demands -- as well as a longing for companionship -- nearly sink her for most of the marvelous, two-toned 8.5 x 6 inch pages here.

Renderings of ads play a significant role in Shoplifter's panel composition. Having suffered through a job editing economic analysis after college -- the refrigerated multi-grain bread of English major careers -- Cho's arc for his copywriter felt close to my heart, but it's a bit too familiar, and not just because I've lived it. The narrative, a character sketch affixed to a structured timeline that neatly culminates in a 1990s indie film-like epiphany, is perhaps the kind of story that Park might have been assigned to read as an undergrad. Conventional self-examination materializes on her humdrum commute to work, where inward-peering yields and emphasizes the kind of apathy toward day jobs that we've frequently seen encountered by mopey types in Daniel Clowes's efforts, or in the short stories collected in Adrian Tomine's Optic Nerve series. Cho's work on the story's setting, and his focus (if heavy-handed) on the wider-spanning issues that are introduced as a result of his character's arc, is far more impressive.

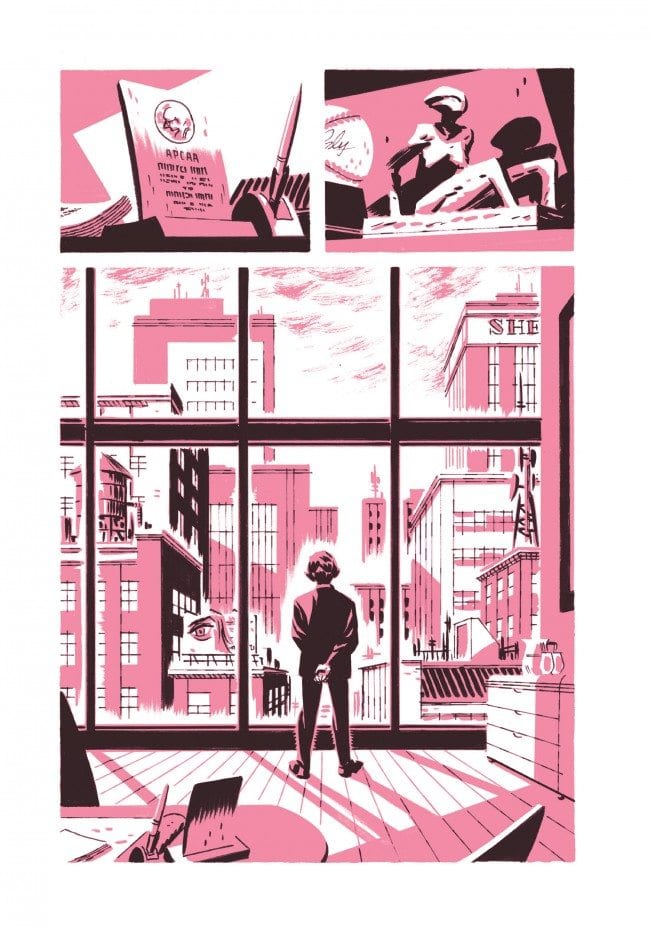

Sleek, big oak doors with pronounced wood grain textures characterize Park's office, and floor-to-ceiling windows give way to Cho's cascading building fronts and wealth of billboards. Ad copy and serial appearances of typography in general are ubiquitous in the book — train car cards link to one another along the top ridge of the subway car during Park's commute, while pasted flyers and concert handbills engulf her when she ascends the train platform. She attends an obnoxious nightclub launch party for a brand that specializes in marketing via a social network, and the streets of Cho's book are streaked with big, bold ad endeavors every step of the way. Copywriting isn't so visually integrated in Park's story simply for the purposes of highlighting her soul-crushing role at a high-end marketing agency; Cho is examining our social habits and how we interact with advertising as consumers. This is better communicated visually -- overheard chatter at the club as well as a flirty conversation that Park has about social networks with a freelance photographer named Ben come off as labored and unrealistic. In flashy street billboards (which hang above hordes of passers-by whose faces are buried in digital devices), in labels spilling out of Park's grocery bag, and in the heavily branded foodstuffs squabbling for space at the minimart, however, Cho aptly explores and demonstrates how inundated we are with branding and marketing's reach.

Even as she reluctantly brainstorms at pitch meetings for packaging children's perfume in Shoplifter, Park questions our relationship with brands and mocks the general public's fixation on social networking (vis a vis online dating profiles and our digital selves — the "tiny pictures and status updates," she says). The difficulty that the comic's copywriter has with "marketing" herself for the purposes of pleasing a paternalistic creative director or improving her personal life pairs nastily with a case of social anxiety and a bit of hating on her job. Coping comes with infrequent shoplifting, an act of defiance toward mass consumerism as well as a thrill, even in abbreviated doses — stop-offs at her local market mean that she'll tuck a magazine into a newspaper on her way to the register. Cho crafts the first episode with swift perspective pivoting that plants the reader in front of the counter, behind the counter, and perhaps from the vantage of a security camera. His application of the book's soft pink tone is a bit similar to how Hope Larson employed blue-grey in depicting the expressive cast of her 2012 adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time. Cho splashes rose across the periodicals rack for contrast and depth or uses it to trace the black contour lines that shape the curve of Park's face as she ducks the market's overhead lights. He plays with the text, too, so that a step-by-step rundown of "Corrina Park's Guide to (Small Time) Shoplifting" breaks with convention to slip us alongside his petite thief.

Even as she reluctantly brainstorms at pitch meetings for packaging children's perfume in Shoplifter, Park questions our relationship with brands and mocks the general public's fixation on social networking (vis a vis online dating profiles and our digital selves — the "tiny pictures and status updates," she says). The difficulty that the comic's copywriter has with "marketing" herself for the purposes of pleasing a paternalistic creative director or improving her personal life pairs nastily with a case of social anxiety and a bit of hating on her job. Coping comes with infrequent shoplifting, an act of defiance toward mass consumerism as well as a thrill, even in abbreviated doses — stop-offs at her local market mean that she'll tuck a magazine into a newspaper on her way to the register. Cho crafts the first episode with swift perspective pivoting that plants the reader in front of the counter, behind the counter, and perhaps from the vantage of a security camera. His application of the book's soft pink tone is a bit similar to how Hope Larson employed blue-grey in depicting the expressive cast of her 2012 adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time. Cho splashes rose across the periodicals rack for contrast and depth or uses it to trace the black contour lines that shape the curve of Park's face as she ducks the market's overhead lights. He plays with the text, too, so that a step-by-step rundown of "Corrina Park's Guide to (Small Time) Shoplifting" breaks with convention to slip us alongside his petite thief.

The budding kleptomania in Shoplifter isn't as extreme a case as the one that Canadian comics creator Pascal Girard recounts in 2014's funny and also love-and-misdemeanor-driven Petty Theft, but like Girard's Sarah, who calls book-stealing "a bit of a rush," Corrina Park finds comfort in the inherent sense of danger. Exiting the store with stolen goods is a break from the hours she spends fantasizing about leading an isolated novelist's life or mulling her own overt difficulty with interaction: "I'm so bad at groups," she confesses. "Sometimes when everyone is talking, I start to get self-conscious." Peeking out from under a head of black bobbed hair that never quite crests the shoulders of her peers, Park is cast as diminutive, disconnected, and alone, even in an enormous city that's overrun with people.

The budding kleptomania in Shoplifter isn't as extreme a case as the one that Canadian comics creator Pascal Girard recounts in 2014's funny and also love-and-misdemeanor-driven Petty Theft, but like Girard's Sarah, who calls book-stealing "a bit of a rush," Corrina Park finds comfort in the inherent sense of danger. Exiting the store with stolen goods is a break from the hours she spends fantasizing about leading an isolated novelist's life or mulling her own overt difficulty with interaction: "I'm so bad at groups," she confesses. "Sometimes when everyone is talking, I start to get self-conscious." Peeking out from under a head of black bobbed hair that never quite crests the shoulders of her peers, Park is cast as diminutive, disconnected, and alone, even in an enormous city that's overrun with people.

Shoplifter's metropolitan setting is integral to Park's days — arched windows cap the tenement facades visible from her spare and compact one-bedroom apartment, where Cho mixes up his page with a series of faux Web browser pop-ups in lieu of panels. They're either spam or sleaze, and Park's latest online dating session tanks upon login. On busy streets during her commute, she's swallowed-up by panoramic clusters of slender, vertical skyscraper window panes and thick, boxed-off low-rises, all built in blotty rose-pink strips and shaded with loads of black strokes. While Shoplifter's urban exteriors resemble the 1960s-era big-city landscapes in Darwyn Cooke's comics adaptations of Donald "Richard Stark" Westlake's books, Cho has long prized an urban setting over anything else. For Penguin's 25th anniversary edition of Don Delillo's White Noise, Cho's book jacket art is ideal, a visual embodiment of his interests in graphic design, billboard advertising, and our relationship with media (and incidentally built mostly of two colors). More recently, the creator explored city architecture in an evocative 2012 art book called Back Alleys and Urban Landscapes, a collection of Toronto scenery -- wordless pages of delicately painted or ink marker’ed row homes, often confined to two tones -- produced over a five-year period. Back Alleys' imprint is discernible throughout most of Shoplifter, particularly when an elevated subway train in a splash page snakes across a North Brooklyn, New York City-like borough. The faint traces of a populous urban center looms in the background. Cho reduces the city skyline to a ridge of crude pink dashes, dispensing with his precise black linework to lessen its potency so that our eyes set mostly on the low-rises in the fore, where the tops of bushy trees curl beneath a deft exercise in shading that magnifies the frame of the train tracks. Far adrift from Shoplifter's albeit stirring portraits of crowded city living and near-onslaught of ad copy depictions, this is among the book's most fetching illustrations. And it's probably no accident that it's little more than a fleeting glance at the sort of pastoral, branding-free solitude that seems just beyond Park's grasp.

Shoplifter's metropolitan setting is integral to Park's days — arched windows cap the tenement facades visible from her spare and compact one-bedroom apartment, where Cho mixes up his page with a series of faux Web browser pop-ups in lieu of panels. They're either spam or sleaze, and Park's latest online dating session tanks upon login. On busy streets during her commute, she's swallowed-up by panoramic clusters of slender, vertical skyscraper window panes and thick, boxed-off low-rises, all built in blotty rose-pink strips and shaded with loads of black strokes. While Shoplifter's urban exteriors resemble the 1960s-era big-city landscapes in Darwyn Cooke's comics adaptations of Donald "Richard Stark" Westlake's books, Cho has long prized an urban setting over anything else. For Penguin's 25th anniversary edition of Don Delillo's White Noise, Cho's book jacket art is ideal, a visual embodiment of his interests in graphic design, billboard advertising, and our relationship with media (and incidentally built mostly of two colors). More recently, the creator explored city architecture in an evocative 2012 art book called Back Alleys and Urban Landscapes, a collection of Toronto scenery -- wordless pages of delicately painted or ink marker’ed row homes, often confined to two tones -- produced over a five-year period. Back Alleys' imprint is discernible throughout most of Shoplifter, particularly when an elevated subway train in a splash page snakes across a North Brooklyn, New York City-like borough. The faint traces of a populous urban center looms in the background. Cho reduces the city skyline to a ridge of crude pink dashes, dispensing with his precise black linework to lessen its potency so that our eyes set mostly on the low-rises in the fore, where the tops of bushy trees curl beneath a deft exercise in shading that magnifies the frame of the train tracks. Far adrift from Shoplifter's albeit stirring portraits of crowded city living and near-onslaught of ad copy depictions, this is among the book's most fetching illustrations. And it's probably no accident that it's little more than a fleeting glance at the sort of pastoral, branding-free solitude that seems just beyond Park's grasp.