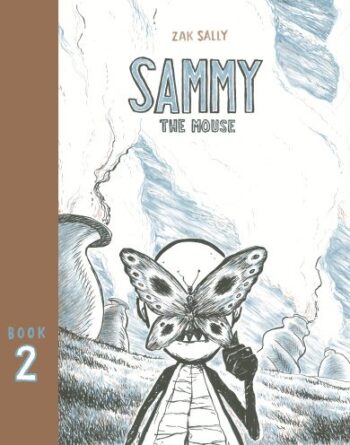

Zak Sally's personal, visceral, and bleakly hilarious Sammy the Mouse Book 2 sees its assortment of sad sacks and lunatics pulled along in what's beginning to resemble a plot. This project has gone through a few different publishing incarnations, beginning with three separate issues published by Fantagraphics through its now-defunct Ignatz line (edited by Igort and co-published by Coconino Press) and then a collection published through Sally's own La Mano. That first volume was quite literally hand-published and put together on Sally's own press, an enervating task that he did not want to repeat. That's how Tom Kaczynski and Uncivilized Books got involved. The result is a book that precisely mimics the digest-sized format of the first collection, though it necessarily lacks the rough edges that gave that first volume a certain intimacy and charm. However, the fact that this is not a hand-made object doesn't detract from the story nor the way the book looks; it's simply a bit of an added-value feature that's no longer present for reasons that make sense.

Zak Sally's personal, visceral, and bleakly hilarious Sammy the Mouse Book 2 sees its assortment of sad sacks and lunatics pulled along in what's beginning to resemble a plot. This project has gone through a few different publishing incarnations, beginning with three separate issues published by Fantagraphics through its now-defunct Ignatz line (edited by Igort and co-published by Coconino Press) and then a collection published through Sally's own La Mano. That first volume was quite literally hand-published and put together on Sally's own press, an enervating task that he did not want to repeat. That's how Tom Kaczynski and Uncivilized Books got involved. The result is a book that precisely mimics the digest-sized format of the first collection, though it necessarily lacks the rough edges that gave that first volume a certain intimacy and charm. However, the fact that this is not a hand-made object doesn't detract from the story nor the way the book looks; it's simply a bit of an added-value feature that's no longer present for reasons that make sense.

If the first volume saw the book's characters wandering around aimlessly, desperately looking for something to do while also desperately trying to avoid responsibility, then this volume sees them moving with determination and purpose. It's not always clear as to what that purpose is, but there is at least forward movement. Sammy has been told to dig a hole by the unseen voice in the sky, so that's what he does. The unnamed woman who has an insane crush on him is looking for Sammy to give him a pie. Carl Urbanski finally delivers his load to Puppy-Boy, a character whose motivations are as shadowy as they are desperate. Even the hilarious, drunken Feekes has a few tricks up his sleeve. The mysterious, monstrous creatures who seem to be the straws that stir the narrative drink are moving around. There's still a bullet flying through the air, whose destination is unknown. There's still an unseen couple arguing in a house.

What all this means for Sally in this volume is the possibility of action and motion. These are all cartoon characters, after all. They're all living in the same city as every cartoon character ever, and that city is grungy, strange, and not all that friendly. So when Feekes hops from bar stool to bar stool and then "sproings" up to sit next to Sammy, it's a perfectly natural Looney Tunes sort of moment. That sense that every cartoon character from Dr. Seuss to the present is reinforced when Peter Bagge's Goon on the Moon pops up at the bar to annoy Sammy and when Kim Deitch's Waldo is the one who pays Urbanski (a sort of grown-up version of Charlie Brown, down to the zig-zag-striped shirt). The world of Sammy the Mouse is not unlike Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead: What are the characters doing when they're not in adventures? What are they doing on their days off? I imagine for Sally, a former professional touring musician, this had to be a question that constantly dogged him. That's why this comic feels so personal, even as it's filtered through an anthropomorphic comics lens that bends reality when the narrative needs it to be bent.

That world is at once timeless, modern and nostalgic. Sally takes cues from Deitch and Bagge as two of his obvious comics heroes, to be sure. From Deitch, there's that obsession with bygone eras and a discomfort with the modern world. From Bagge, there's that exaggerated and rubbery character interaction and hilarious screaming matches, not to mention riffs on substance abuse. Floyd Gottfredson, EC Segar, and George Herriman are other obvious touchstones. This book is not autobiographical in the sense that's it's not literally about specific, true events, but it's entirely autobiographical in that it depicts the way it felt (and feels) to be an artist, to be consumed by a "project," to self-medicate one's emotional pain by drinking, to negotiate a world full of people whose methods of communication are entirely one-way, and to alternately try to address and flee from moments of authenticity. Taking his cues from an earlier generation of artists gives the book to date a timeless look for a timeless dilemma, making a personal story that much more accessible.

By the end of the book, Sally gives the readers answers, but not explanations. Sammy finally finds his way back to Puppy Boy (in the most roundabout way possible). Puppy Boy finally shows him his mysterious secret project in a big two-page spread, but precisely what it is is unclear. We learn just what Urbanski got as payment for hauling something to Puppy Boy after it was wrapped in bandages and later stolen by Feekes, but we have no idea why it's significant. The nameless woman bursts into Sammy's home but finds nothing but a bunny suit. If I recall correctly, the end of this volume is the halfway point of the series, so the way Sally pulls the rug out from under his readers makes sense and is in a way the final gag of the book. It's the reader who does the "plop take" after being led along for an entire book, only to find that they were led directly into a brick wall like the Roadrunner and the Coyote.

The appeal of Sally's art has always been that careful dance of beautifully rendered images that are meant to be slightly ugly and even repulsive. The Seussian buildings of the city here are grey and dingy, highlighted by the book's sepia tones. Even the blue-green tone that dominates the book is faded, as though every place is dimly lit and dreary. Sally's character design is clever, even as everyone looks a bit run-down, tired and shabby. Though the story's only half done as of this volume, reading it feels like Sally is snapping a rubber at the reader, a clever little shock that reminds us that he's "going somewhere, I promise" with all this, as "sincerely, no one" assures us on the book's French flaps.