For nearly three decades, Chris Ware has been making comics that capture the intersection between action and consciousness. His first novel, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (2000) condenses over a century's worth of memory into one fraught Thanksgiving weekend. Inert and awkward, Corrigan is the prototypical Ware lead, a misfit stuck in his own imagination. Jimmy Corrigan, a sad, enrapturing story told in Ware's bold, innovative style, was a huge crossover hit. The novel remains a challenging read, deploying a range of postmodern and metamodern techniques that Ware would develop, refine, and reinvent over the course of his career, establishing his own grammar of storytelling.

Building Stories (2012), Ware's follow up to Jimmy Corrigan, exploded that grammar of storytelling. Comprised of fourteen books of different sizes and housed in a giant box (itself part of the story), Building Stories dared readers to put together a narrative themselves. The novel is fractured and grand, dizzying and satisfying in its elisions and disruptions. Most of the characters go unnamed. Resolutions for a story in one of the fourteen books might be found in another volume, regardless of what order the reader tries to impose on the narrative. Building Stories is one of the foremost post-postmodern novels in our young millennia, but because of its bulky unwieldiness (and frankly its strangeness), it remains under-read, even if it was critically praised upon its publication.

Rusty Brown, Ware's latest novel (or, more precisely, novel-in-progress) strengthens the argument that Ware is a Serious American Novelist, one who deserves a large crossover audience. Like Jimmy Corrigan and Building Stories, Rusty Brown has a central primary setting, a small private school in Nebraska. And like those novels, Rusty Brown comprises material (lightly reworked) from Ware's Acme Novelty Library series (issues 16, 17, 19, and 20, specifically). The cast here is much larger and the themes are arguably more ambitious though.

Rusty Brown is a sprawling story about memory and perception, about minor triumphs and chronic failures, about how our inner monologues might not match up to the reality around us. In Ware's world, life can be blurry, spotty, fragmented. His characters are so bound up in their own consciousnesses that they cannot see the bigger picture that frames them.

Appropriate to this theme, Ware frames his novel as a day of network television programming, beginning with the beautiful program "Snow" (aka "Our Science Minute"). The two-page chapter is a brief, simple meditation on snowflakes. Can we be so sure that no two are truly alike? the cursive-voiced narrator wonders. The final paragraph of "Snow" subtly announces one of Rusty Brown's major themes:

Like the growing rings of a tiny hexagonal tree, billions of water molecules spin around and around, each finding the closest, easiest, and most comfortable bond (just as people, who seek the companionship of like minds and bodies, cannot simply be thrown together and expect to thrive)...

The characters of Rusty Brown are stuck in miserable "easy" bonds; thrown together, they do not thrive.

The prose of "Snow" is set against, as one would expect, a lovely rendering of snowflakes falling. The final paragraph however breaks off into a rude red "TSSHHT" -- the channel has been turned, and, as we in turn turn the page, we find ourselves in a new kind of snow---the white noise of analog television static, with the title card RUSTY BROWN superimposed. The graceful dots of water molecules transforming into snowflakes shifts into something harsher, buzzier; our camera then pulls out to reveal our cast of characters---again, framed in dots.

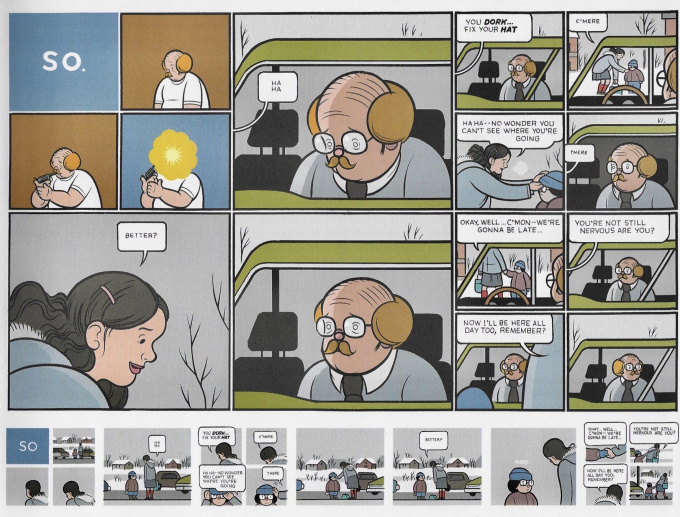

We turn the page, and snowflake-filled dots take us into the next chapter, "Introduction." These snowflakes also lead us to two parallel tracks: the Browns and the Whites. For about fifty pages, the narrative of bullied loner Rusty Brown and his mean, sad-sack father Woody Brown runs concurrent to the story of siblings Alice White and Chalky White's first day at their new school. Rusty and Chalky are in the same class, and Woody is an English teacher there. The bifurcated narrative structure allows us to see not only what the characters see, but also how the characters see each other. The results are often moving.

We also meet the rest of the cast, including Joanne Cole, who teaches Rusty's class, Jordan Lint, who bullies Rusty mercilessly, and Franklin Christenson Ware as "Mr. Ware" a pretentious art teacher who tries to look up his students' skirts. (Ware also smokes weed with Jordan in the parking lot in a scene that is simultaneously hilarious and pathetic.)

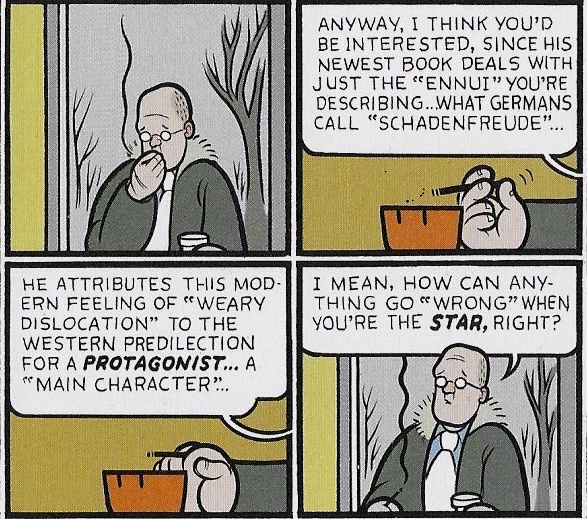

Ware's insertion of a version of himself into his story is a pretty standard postmodern move, but it never feels gimmicky or irritating in Rusty Brown, perhaps because Ware's alter-ego here is both pompous and pitiable. He's a version of Ware that never made it, a windbag who mixes up "ennui" and "schadenfreude." He's not the star of this show.

"Mr. Ware" creates what he concedes "could be called 'Pop Art,'" but unlike Lichtenstein who "employs a mechanical technique to make his 'dots,'" Mr. Ware proudly renders his dots by hand. The metafictional gesture here invites the reader to pay closer attention to dots, frames, and ways of seeing.

The ostensible star of "Introduction" is not Mr. Ware but Rusty Brown of course. Rusty awakes on this particular day to discover that he has gained superpowers. Well---a superpower: listening. He transforms (in his imagination) into Ear Man. Unfortunately super-listening can't save him from being bullied by Jordan. Ware takes us into his hero's memory in a scene that captures humiliation, pathos, and black humor:

Poor Rusty!

In his imagination he's the hero though, and he daydreams through class about saving Supergirl. He secrets a Supergirl action figure into class with him, a conceit that adds much of the drama to "Introduction" and also initiates his awkward friendship with Chalky.

The Supergirl motif reinforces Ware's larger themes of voyeurism and the male gaze. The adult males in Rusty Brown leer and lurk, and we get the sense that young Rusty will follow that skeevy path. Rusty fetishizes his Supergirl totem; his doll is literally an object conjured into a subject via imagination, a subject whose nakedness "makes perfect sense" to our prepubescent protagonist:

Ware jumps into the memories and imaginations of his characters in "Introduction," but these moments follow a standard grammar of narrative sequential art. Aside from the device of running two parallel sequences, Rusty Brown's opening chapter is fairly linear and serves as an overture, establishing characters, setting, conflict, and major themes. The following three chapters of Rusty Brown are more formally challenging (and arguably much stronger).

The second chapter "William Brown" focuses on Rusty's father, Woody. The chapter begins with an abrupt shift: we move from snowy Nebraska to arid Mars. And not just any Mars, but a particularly 1950's vision of life on Mars.

For fourteen increasingly-intense pages, Ware tells the story of two couples who attempt to colonize Mars (with some dogs in tow). I will not spoil the story-within-the-story here, but only suggest that I read it with mounting horror. The Martian colonist story turns out to be "The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars" by one W.K. Brown, published in a pulp magazine when he was still a very young man.

Ware then takes us on an elaborate trip through Woody's memories of his first (and only real) love affair. As the sequence unfolds, small disjunctions between the narrative voice and the literal images in "The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars" are explained, even as other cracks between reality and perception appear. We can see what Woody cannot see about his love affair; we can also see how this failed romance led to the creation of the one thing he was truly proud of, a pulp fiction story. Ware makes Woody's figurative blindness literal when Woody cracks his glasses on a voyeuristic stalking mission. Ware shows us the world through Woody's cracked lenses, a world that fails to fully cohere, a world of hazy dots that doesn't quite make sense.

In the final panels of "William Brown," Woody, now an older, sadder, fatter man who daydreams of abandoning his family (and even suicide), shaves his mustache, removes his glasses, and stares into the mirror. We see what he sees: A perplexing haze of colored dots. Woody Brown is a hideous man.

Jordan Lint, erstwhile hero of Rusty Brown's third chapter "Jordan Lint," is also a hideous man. While Woody's life is small, cramped, and miserable, Jordan's narrative vacillates with a range of emotions: loss, fear, despair, joy, hope, redemption---and then cycles through those emotions again. Perhaps because it covers an entire life from conception to death, "Jordan Lint" feels like the most achieved of Rusty Brown's four main sections. Continuing his motif of dots and frames, Ware ushers his character into existence:

Jordan is a horrible man, yes, but Ware shows us how a horrible man is made. Born into a very wealthy family with a fine old house, Jordan has every possible advantage and privilege in life. He's nevertheless doomed from the outset. As a young child, Jordan witnesses his father abuse his mother. He also is taught to be a racist by his father, a theme that Ware expands in the next chapter, "Joanne Cole." Jordan's mother dies when he's still young, he fights with his teacher (Ms. Cole, of course), and it's only his father's money that keeps him from being expelled from school. As a teen, he's spoiled and rebellious.

His high school years end in a tragedy of his own making that he is never quite able to answer for. Jordan's negotiation with his role in this tragedy is perhaps the central conflict of "Jordan Lint," as he wavers between faith and despair.

Ware's narrative techniques in "Jordan Lint" are formally daring. The chapter floats through the fragments that make up Jordan's memories. Drug addiction, sex addiction, self-hatred, hatred for his father, religion, family, redemption---and then fucking it all up again---are rendered in stream-of-consciousness. Words play on each other and images repeat with significant differences, as Jordan essentially repeats his life. Ware dares us to pity Jordan, to forgive him his trespasses, and then reveals new horrors that Jordan is blind to. Like Woody Brown, Jordan Lint cannot see that he cannot see. (In one horrifying scene, Jordan spots Rusty Brown in the grocery store and approaches him as if he were an old friend. Rusty runs away.) Blind to his own blindness, Jordan ends life alone, unforgiven, with nothing but his own misery revealed to him.

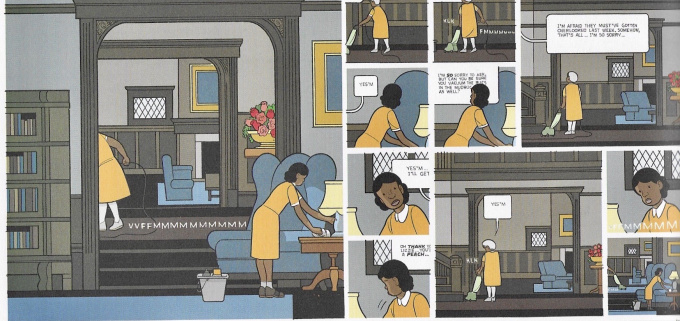

Joanne Cole, hero of "Joanne Cole," is significantly more sympathetic than Woody Brown or Jordan Lint. Like Woody, Joanne's life is far more confined than Jordan's. She lives a series of mundane repetitions: taking care of her mother in the small apartment they share, taking the bus to work, teaching students at a predominantly-white private school, taking the bus home, preparing dinner, sleeping. However, unlike, Woody, she finds meaning in her life through religion, music, and a seemingly-endless literal search for something that she performs in the school's library (via microfiche and later the internet) after school each day.

"Joanne Cole" is told in a fragmentary style similar to the approach Ware takes in "Jordan Lint." The narrative moves forward, punctuated by Joanne's memories of her childhood. We see her growing up very poor, taking care of her younger sister, and working with her mother to clean the Lint home.

By the time we get to "Joanne Cole," we've already seen her as a support character in the previous chapters. When Ware ushers us into her memories and consciousness, we can finally perceive the great pain that is central to her life, and we can see how that pain has colored her previous interactions with Jordan, Woody, and Rusty. These intersections knit the threads of Rusty Brown together, making the novel more than simply the sum of its parts.

Joanne endures the racism of her colleagues, students, and their parents with a kind of forbearance that nears self-punishment. Her world is one of nearly-ascetic self-denial. She seems willfully oblivious to the kind librarian's polite romantic interest in her. Joanne's only real joys are her church and her banjo--and her research.

Joanne finds what she is looking for, but not through her own research. Her time scrolling through microfiche offers other revelations though. In one remarkable scene, Joanne comes across an old newspaper front page showing an attempted lynching by a mob in Omaha.

The faces of the lynchers are grainy dots, yet she gazes at each of them, framing them, making them real.

As Joanne's memories coalesce with the narrative action of the chapter, we soon come to understand both her ascetic forbearance as well as the thrust of her research. I will not spoil the final moments of "Joanne Cole," but simply suggest that they are both cathartic and earned (and also note that they explicitly connect to one of Ware's previous novels).

The final pages of Rusty Brown return us to snowflakes, to those water molecules that spin around in search of the closest, easiest, and most comfortable bond. The image recalls the early narrator's declaration that "people, who seek the companionship of like minds and bodies, cannot simply be thrown together and expect to thrive." The reminder is subtle though, as the dominant colorful phrase INTERMISSION, fraternal twin of the television-snow opening title, springs across the page. Rusty Brown is indeed a novel-in-progress, and it's a testament to Ware's prowess that the first entry, with its emphasis on fragmentation, elision, and lapse, holds together with such emotional and aesthetic coherence. The thing is so damn good. It took Ware eighteen years to put the first part of Rusty Brown together, and although I hope he can deliver the next part before 2037, I'm sure it will be worth the wait. Very highly recommended.