Art imitates life. Or does life imitate art? In comics, unfortunately, the answer is almost always “neither." Here we all are smack in the middle of the most interesting times I've been alive for, but you sure wouldn’t know it going off the view from the comic store. In comics, this year looks the same as the last year - that is to say, a great time to indulge in some escapist entertainment of whatever very particularized flavor you want, true believer! Is escapist entertainment part of the problem in a media climate that resembles nothing more closely than the dancing-hat shell game on the Jumbotron at the baseball park? Meh! Don’t worry about it! For a medium that can make a serious claim to be currently in the process of expanding its worth and scope, comics too often seems blinkered to the world outside the panels. Where are the books with the revolutionary, uncompromising engagement with politics that our times demand?

There are a few reasons it’s such a tough search. Heading up the list is that mainstream action comics’ “nerd culture” (gag) has always been one of the biggest apologists for and believers in market capitalism as a justification unto itself. Alan Moore has left the building and he ain’t coming back. Expecting huge corporations with billion dollar investments in fictional squads of militarized fascists wearing costumes goofier than anything this side of Charlottesville to manifest a relevant political viewpoint is optimistic to say the least. (Unless of course that viewpoint is coming from a former CIA spook or a failed race-baiting politician, but even those guys, along with Ta-Nehisi Coates, soft-pedaled it when it came time to pull their underwear on over their pants.)

Not as obvious but equally pernicious is the fact that a less diseased branch of comics rides the same boat. Those nicely designed “graphic memoirs” (gag) from big book-trade publishers smell a little less like Taco Bell CrunchWrap Supremes and Mountain Dew Code Red, get written up in your favorite liberal media organ, and sometimes even manage to “engage” with “politicized topics". But they too originate from corporate America just like the superheroes do, and go through editors who learned all the wrong lessons from Persepolis and get paid to watch out for dollars and sense, not provoke the retail account holders in white supremacist country. Far too often, the supposedly political bookstore comics end up ladling out the scorching philosophical formulation that people are all basically the same no matter where you go - human beings in need of love and nurturing society. All lives matter!

And so it falls as always to small press and self-published comics to do anything of worth for American comics when they need it. But here too, we are vastly underserved. My read on the inability of alternative comics to deliver anything that feels politically trenchant goes back to milieu. Basically, these things have always looked inward, all the time. Whether it’s Jaime expertly shepherding flawlessly constructed characters through equally flawlessly drawn lives or John Pham obsessively delineating the nooks and crannies of his cartoon cast’s pop culture obsessions or Ben Marra mining and subverting the cliches his own media fascinations deal in, an overwhelming amount of the time alternative comics reject engagement with consensus reality and build a castle of the mind. Aside from a few outliers like Guy Colwell, the history of other comics is all the same. Even the most resolutely reality-based entries in the idiom (Bechdel, Derf, Crumb) restrict themselves to deep dives into the individual selfhood of the artist or a chosen subject, so much so that close relations like parents, friends, and significant others emerge as the major antagonistic forces in their works. The majority of what passes for political engagement in alternative comics is imported from newspaper cartoons: funny and/or rude drawings of the guy you don't like. Which is fine! But these times ask for more. To read the best of US comics, you’d be stumped as to what kind of political system this country runs, let alone what kind of job it’s doing.

But anyway, for at least the past three or four years, alternative comics in the UK have been better and more interesting than the stuff we’re doing stateside. They’re making cooler looking shit over there, but there’s also a feeling of political commitment to the work most of the UK scene’s best artists bring to the table. This sense of relevance and urgency is communicated most clearly by the country’s two leading anthologies, Mould Map and Decadence. Both wear geopolitics on their sleeve as a main motivating principle, and both have solved the age-old comics problem of how to make themed anthologies at all interesting by simply directing their artists to look up from their drawing tables and out at the nightmarish hellscape that corporations and politicians are steering us toward with ever-increasing speed. To my mind, 2014’s Mould Map 3 is the most impressive statement the politicized wing of UK comics has mustered: a blazingly dour and often virtuosic look at a (post) apocalyptic future that bears so many recognizable facets it might just be happening today.

Maybe it’s because they all grow up reading Judge Dredd, by far the most politically interesting of the long-running hero serials for the simple reason that it makes its fascistic subtext into text, but whatever the reason all relevance doesn’t dissolve when Brits do comics about fighting. Often it even manages to grow. To that point, my favorite piece in Mould Map 3 was by British artist Joseph P. Kelly. A slightly nonlinear look at the revolutionary hero of a Heavy Metal-inspired technofuturistic city, it imported an idiom and drawing style direct from action comics. Perfectly drawn weapons and vehicles gave the run-and-gun battles it threw out glimpses of a weight that went beyond single panels, and its intimations of tragedy were deepened by Kelly’s sturdy and accurate cartoon realism. Like the best short comics, it was notable not so much for what it delivered as what it hinted at: a vision of comic books with pointed political content carried off with an assured use of the razzle-dazzle lingua franca that superheroes trade in.

In his new graphic novel PayWall, Kelly pays down the promissory note of that Mould Map piece. Handsomely printed by Mould Map editor Hugh Frost's publishing boutique Landfill Editions, it is work so relevant and contemporary that it seems to belong in a completely different ballpark than the rest of what comics has on display right now. Set in an English coastal city ten years from now, PayWall depicts a society in which rising sea levels threaten human survival, parking lots full of live-in port-a-potties are replacing apartment blocks, and the federal government and military have been torn to pieces and swallowed by a rabid pack of competing corporations.

At its heart, this is an entry in that most recognizable of comic book genres, the hero's origin story. Rather than create his hero as a slightly more ridiculously costumed version of a police officer, though, Kelly looks for inspiration at the real heroes of today's world: the scared, angry young people pulling on masks and taking to the streets to put their bodies on the line against governmental and societal oppression. PayWall's hero team is a cell of militarized anarchists, its villains a loosely knit cabal of rich corporate dickheads who have reformed the world in their image, and its protagonist a regular working dude who is radicalized by the radical situation he finds himself in.

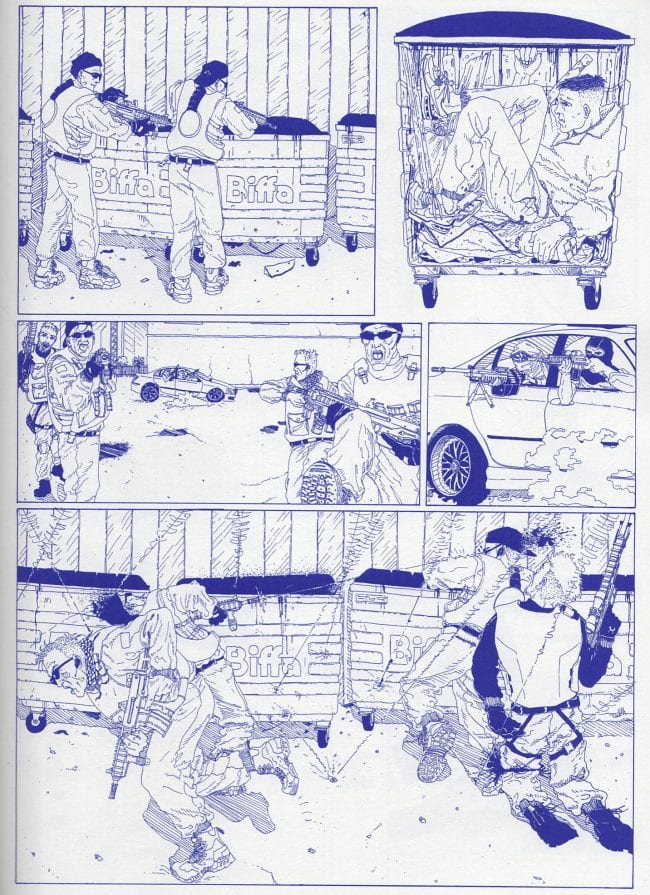

Kelly's drawing pulls as much weight as his plot in establishing the sense that you're reading something that could be happening right down the street. This is highly accomplished naturalistic drawing, individual and unique but assured enough that it could easily be published in an Image comic if you threw some shitty computer colors on top of it. Kelly actually does do this at points, giving the segments of his book that depict TV broadcasts an eerie, blue-toned sheen perfectly in keeping with the tone of cable news. Most of the time, however, it's just a thin, almost scribbly line up against white paper, knocking out big powerful drawings of perfectly observed back alleys, warehouses, and milling crowds. Kelly's style probably looks closest to Tim Bradstreet's (of all people); but while it's clear he utilizes plenty of photo reference to give his work its double take-inducing quality of realism, his line is loose enough and his figures expressive enough to keep things flowing. Here is a far more considered use of photo reference than one sees in mainstream comics, one that has more to do with Google Images than rounding up friends to pose and shoot in your backyard. The important stuff in these panels is clearly drawn, not traced - but key details are ripped directly from recent back issues of TrailRunner and Guns & Ammo. PayWall doubles as a militancy-themed collection of great fashion drawings, to be filed under "Athleisure". And thank God Kelly is aware of the power visual narratives accrue when they star young, attractive people! It’s a lesson that was perhaps the first the movies learned but that good comics still too often seem ignorant of.

The dialogue is pitched to match the drawings - loose and slangy, with a slight savor born of observation and a keen ear. In a short comic with a large cast, the word balloons are forced to do a large percentage of the lifting when it comes to creating characters out of a bunch of really cool drawings, and Kelly's perform admirably. A conversation between two friends about unemployment and bills is almost depressingly realistic, while lines like "I'm a soldier. I know what my purpose is," uttered by a revolutionary going to certain death earn their proper weight when they rise from the colloquial muck.

The thrill of familiarity is no small part of what makes Kelly's book so exciting - just like in classic Marvel comics, here are some heroes with problems and concerns that you can get behind! But it goes deeper. In most action comics both the plot machinations leading to violence and the violence itself are so remote from reality that they take on an almost ritualistic quality, one enhanced by their repetitiveness, that ultimately serves to keep even the gnarliest set piece from making much of an impact. By contrast, Kelly couches his comic's violence in frighteningly plausible scenarios, and it's tough to keep from pumping your fist when you see a paramilitary asshole get his fucking head run over by a car. The violence in PayWall is quick and sudden and often inexplicable, like the real thing. When a sniper's shots ring out and wipe a character off the map just as you were getting to like him, it's not telegraphed by panels of shadowy figures lurking in windows or crosshairs fixing on the dude's head. One panel he's running down the street, then you turn the page and he's done, face down and bleeding into the gutter.

It's this kind of approach, a commitment to observational realism and not the comic book style of it we've all become accustomed to, that makes for such a bracing read. It's as if Kelly is holding every element of his book up to the light and searching for the most direct way to put it. If that breaks the previously established rules of comics, well, he credits his audience with enough brain power to keep up. The little things here add up to a much bigger, richer picture. From the way a drawing of a package of cream cheese comes complete with the full Philadelphia branding to the profusion of actually-really-good corporate logos designed for the story's many-headed hydra of villains, there's simply more care than average put into this comic, a desire to take even its most generic visual aspects into the realm of the notable. And that care is earned! Kelly is writing about important shit - making a comic that concerns you whether or not you share its artist's exact interests.

PayWall is not a perfect comic. Kelly's published page count is still hovering somewhere in the area between two and three figures, and in places it shows. Some of the panel compositions in the slower dialogue scenes lack the grandeur of Kelly's Mould Map story. The book's conclusion feels rushed and relies on an EC-style twist to extricate itself from a plot that could (and if you ask me, should) keep going for at least the same length it's already run. While it's hardly bad form to keep your readers wanting more, there's so much crammed into these pages that a bit of breathing room to explore the highly compelling world Kelly has created would hardly go askance. Still, the charge this thing carries would be enough to overcome twice its problems.

“People were coming in off the streets, coming into a performance arena where they were hoping they’d be escaping, and all we were doing was shoving the streets back in their faces,” said revolutionary propagandist Alan Vega about his work in the band Suicide. In PayWall Joseph P. Kelly turns comics to the same necessary and admirable task. Within the Trojan horse of escapist action entertainment is a sophisticated and brutal allegory for the political drama outside our windows - and a warning about what might be lurking inside our phone plans, our employment contracts, our future. But this is no depressing, Orwellian vision of unstoppable doom. The escape on offer here leads not into fantasy, but through the mirror into an attainable reality, one where a mask and a gun and a plan of action is all you need to take on the bad guys. While I was reading this comic I sometimes felt like I was reading Guy Colwell's political barnburner Inner City Romance again for the first time. At other points I felt like I was back as an eleven year old getting my sweet li'l mind blown by Mark Millar's Authority. Kelly's book demands a visceral reaction; it demands to be read. Get on it.