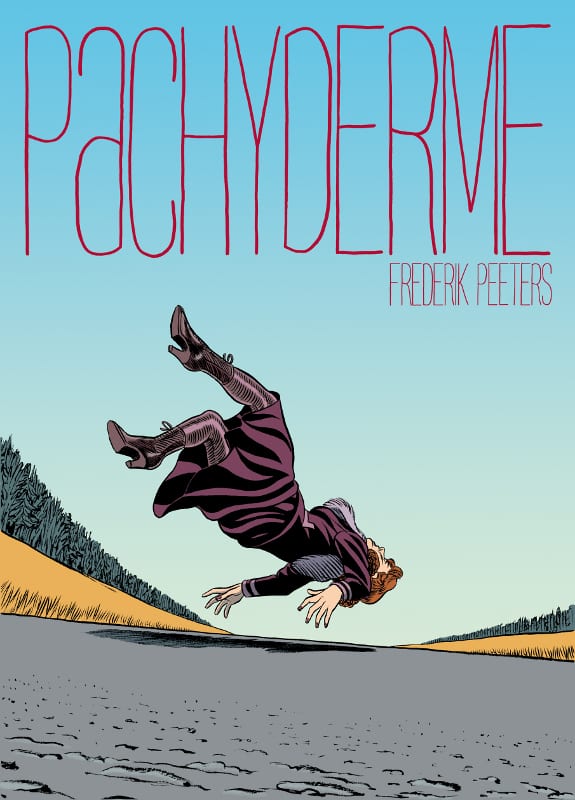

Frederik Peeters’ Pachyderme opens in 1951 in Switzerland, with a scene of a woman walking through a traffic jam on a forest road. Old automobiles are lined up nose to tail, drivers are yelling at each other. It’s a realistic scene, conveyed with meticulous period detail. Turn the page however and the same detail is applied to a shot from above of an elephant, lying in the middle of the road, evidently wounded, extreme panic in its eye. As Moebius points out in his introduction, the overhead angle is suggestive of a crime-scene photo. But how did the elephant get there? What kind of story are we reading?

Over the next couple of pages, we learn—to some extent. Carice Sorel, the woman we encountered walking through the cars leaves the road and walks through a forest. In the forest she encounters a blind keeper of pigs, then waves at a huge, dead-looking hydroencephalic baby before arriving at a large hospital where her husband is being treated… although not before the narrative has looped backward/forwards/sideways (it is not clear which) to a scene in an elegant mid-century room where she is depicted placing a letter to her husband in her handbag. We are not privy to the contents of the letter, but there is an atmosphere of finality; she strikes a single note on a piano as she leaves. Our sense of time, reality and location duly disrupted, Peeters now cuts to a scene where a patient lies on an operating table, his back slit open, and then the operating surgeon bursts into song. This is the mysterious hospital where Carice will search for her husband, a hospital where strange and dreamlike events multiply…

Clearly Peeters is operating in “surreal” or even “Lynchian” territory here. Dreaded words, these, so often casually evoked by lazy critics looking for a quick shorthand to evoke something a bit weird. But in Pachyderme’s case, they are justified. In particular, Pachyderme bears several direct comparisons to David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive: it opens with a car crash, is structured around the quest of a woman for answers, and as Carice continues on her quest it seems increasingly likely that Peeters is depicting a fugue state.

But Peeters' dream-surrealism has a different texture than Lynch's; the flowering vagina wall, talking corpse, phallic-nosed secret agent, and mysterious cold war sub-plot are all his own. The dead elephant recalled for me the funeral scene for the pachyderm in Jodorowsky’s berserk movie Santa Sangre. At the same time, given that Peeters is working in a Swiss/Central European context, there are undoubtedly other contributing factors to the narrative and art that many Anglophone readers will be oblivious to; literary, cinematic and other seeds Peeters is planting most of us will not pick up on. For instance, in an interview cited by his (skilled) translator Edward Gauvin, Peeters stressed the influence not of Lynch but rather the Austrian author Stefan Zweig: “I wanted to make it exotic. I thought a lot about Stefan Zweig’s novella ‘Letter from an Unknown Woman.’” Pachyderme is also more elegantly structured than Lynch’s movie: the realistic scenes set outside the hospital, occurring at strategic points in the narrative, hint at what lies behind the fugue state and establish an added layer of mystery/tension that draws the reader forward.

Thus, in spite of the abundance of weird imagery – which was undoubtedly fun for Peeters to draw – Pachyderme is clearly the work of a disciplined and thoughtful creator. For while Peeters has a wonderful, fluid line and obviously loves to sling the ink around, the world he draws is precisely designed right down to the wallpaper, and contained in tight panels, sometimes as many as twelve to a page. Interior scenes, more often than not, occur in cluttered, windowless rooms, heavy with ornate furniture, rich in claustrophobic detail. The color scheme is autumnal, muted. All of this keeps the fantasy grounded. So too does the pace, for in Pachyderme Carice walks, and she has a lot of detailed panels to walk through. Peeters forces the reader to slow down, to read what she and the other characters are saying, to reflect upon sudden changes in mood, subtle changes of expression.

I keep returning to the exchange on page 47, in one of the “realistic” scenes when Carice, who is a piano teacher, is presented with an elephant pendant (the first occurrence of the motif since we encountered the injured, panicked elephant at the start of the book). Now directly identified with that wounded animal, Carice is suddenly and unexpectedly kissed by her young student Audrey. What follows next is a master class in less-is-more aesthetics: the uneasiness and awkwardness of the situation is conveyed in muted yellows and purples, subtle alterations to Peeters’ line as he draws the women’s changed expressions, now shocked, now teasing, and then Carice’s outburst: “Audrey, what’s got into you?” is followed by its mocking repetition by Audrey herself, who erupts in laughter.

The realistic scenes, so muted, restrained and delicately executed, are perhaps my favorite parts of the book. Their position and contribution to the narrative aside, it’s simply a pleasure to see work by an artist with such a strong command of mood, tone, and (especially) facial expressions. But they acquire their power by being embedded in and juxtaposed with the strange, symbol-drenched dreamlike sequences. Peeters follows Carice on her journey through the hospital, sometimes walking, sometimes running, sometimes looping around until we arrive at an ending which is suggestive of hope and a life changed for the better. Unless it too is part of the fugue, the dream, the fantasy: but Peeters- elegant stylist and sophisticated storyteller that he is- isn’t telling.