No One Else, the new graphic novel by R. Kikuo Johnson, is a story set in contemporary Hawaii on the island of Maui (Johnson’s home). Not long after her father dies, Charlene’s dead-beat brother, Robbie, arrives. He does not know that their dad has died. Robbie has come to surprise his nephew on his birthday. Charlene is so overwhelmed by life that she has forgotten that it is her only son’s birthday.

All these characters have strengths -- which are also their faults. Charlene washes her demented dad’s feet at night before he dies, decorates with a cartoony face the slice of toast that she serves her son in the morning, and dutifully goes to her job in a local ER where she is under-appreciated. Her strength as a caregiver leaves no room for self-care. Her brother Robbie, a road musician, is eager to please but ends up pleasing nobody, least of all himself. Brandon, Charlene’s son, sits in the adult siblings' crossfire. The same perseverance and determination that makes him capable of ignoring their conflict also gets him lost and almost killed.

Johnson’s earlier works, Night Fisher (2005), his Toon Book for younger readers, The Shark King, as well as his numerous illustrations (including a masterpiece New Yorker cover on April 5, 2021, depicting an Asian American mom and daughter nervously awaiting a subway) gave some indication of his drafting talents, but No One Else skyrockets him to the upper pantheon of cartoonists making literary fiction thanks to his skillful use of the medium, his deep insight into its characters, and his restraint in telling their stories -- which pushes the reader close to them, to see them with clarity and compassion. If Anton Chekhov was making comics today, they might read like No One Else.

Like Chekhov, Johnson captures the plainness -- and individual particularity -- of ordinary lives on this Earth.

Like Chekhov, what is not shown and said, shows and says plenty. Throughout the book, scenes begin in mid-action with conversations already in progress. Specificity of setting, gesture, costume, and dialogue gives readers all the data needed to fill those gaps, becoming curious visitors, noticing more, guessing, inferring, engaging.

The book opens with a steady beat, like the ticking of a clock, in six evenly spaced equal-sized rectangular panels. Before even beginning to decode the information within the panels, this overall six-panel structure initiates a methodical cohesion that continues throughout the rest of the book -- except at the times when the pattern and color are, temporarily, purposely broken for impact. Thus the panel size is not influencing the reading of the emotional topography of the story. That reading is left to the reader. Here is the first page.

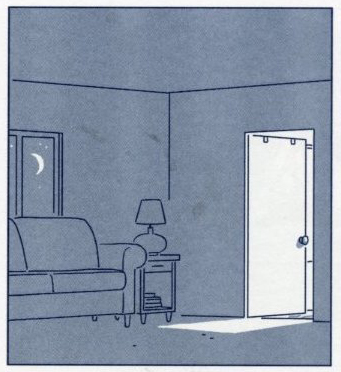

Taking a deeper gaze at the first panel reveals more than just an environment:

The first thing readers learn in the first panel on this first page -- upper left, top of the page, as Westerners read -- is that the story begins at night. This particular aspect of the moon, shaped like a left-hand fingernail, indicates that the moon is waning. In a few days (pages?) there will be no illumination in the night sky, foreshadowing that before long things may get darker. Imagine, instead, this first page with sun blazing outside that window. The moon he has chosen casts a certain light on things.

Moonlight and the diamond of light from the door shine on what clearly is a living room: a crisp couch, a side table holding a neat stack of reading matter, and a lamp, perhaps from a decade earlier than ours. Tiny flecks of texture on the floor (echoing the pinpoint stars outside) indicate either wall-to-wall carpeting or bits of floor dirt.

The room is detailed but also sparse. Why is it so tidy? Why are the walls bare? Is this a new rental? Are the tenants clean freaks? Do they need orderliness?

Through employing specific details, the first panel is much more than merely an "establishing shot." Johnson already has the reader asking questions, wanting to learn more.

The rest of page one provokes more questions, more reasons to continue reading: Is this a book about caregiving? What’s she doing? Is this a nightly ritual? Why can’t dad care for himself? Is dad unable to follow instructions?” Is he old? Near death? Are they alone in the house?

And that’s just page one.

No One Else moves chronologically, each short scene seamlessly building on the previous one. Charlene gets wound tighter and tighter, navigating huge hurdles in applying to medical school at the cost of familial duties. Meanwhile, the vagabond Robbie, whose drifter lifestyle has generally shirked responsibility, moves in temporarily, taking on the tasks of organizing dad’s memorial, sympathetically helping Brandon cope with the sudden changes in the household…including the disappearance of Batman, his cat. Set against orange burning fields of sugar cane in the distance, this suburban home is one hot mess.

But the storytelling is tidy.

A particularly tidy section is (largely) silent. depicting Robbie’s search for the missing Brandon as well as the history of Robbie’s relationship with his late dad and Charlene. Robbie has parked his vehicle, unsure of where to begin looking for Brandon. A streetlight snaps on, triggering a memory of a streetlight-lit moment in Robbie’s youth that was the beginning of the end of his relationship with his dad. Johnson’s deft use of color here make it easy to dance between present and past over the next several pages. It’s a remarkable sleight of hand.

No One Else is a two-color comic: blue and orange. Most of the linework is printed in a blue so deep that it is almost black. Full-tilt orange is saved for the raging fires and a special ancestral blanket, but Johnson makes use of a light orange to indicate flashback.

The end is blessedly unpredictable, circular, truthful, and open-ended -- and in all of that, also Chekhovian. Dysfunctional families do not become functional overnight. The concluding "meaning" -- in a surprise that makes perfect sense, dings the motherhood/caretaking bell, and glimmers towards life moving forward -- is left for readers to contemplate. Johnson has provided all the clues a reader needs -- while leaving readers to wonder. What does it mean? What's next?

This is a graphic novel that feels like a long short story in the most satisfying way. One can gobble it up in a single sitting and feel happily sated (its engrossing spell may make it impossible not to read it in one sitting). And yet we want more, more of this storytelling, to be led, say, two houses down the block on Maui to meet and dwell for a while with another oddly ordinary family.

No One Else is charming, funny, a bit wistful and very human, crafted by a master cartoonist -- whose moon is waxing.