This voluminous collection - the first time that Chinese artist Zuo Ma’s work has been available in English - encompasses comics that the artist produced between 2009 and 2013. It’s composed of a series of short stories that bookend the titular long form story that makes up the bulk of the book.

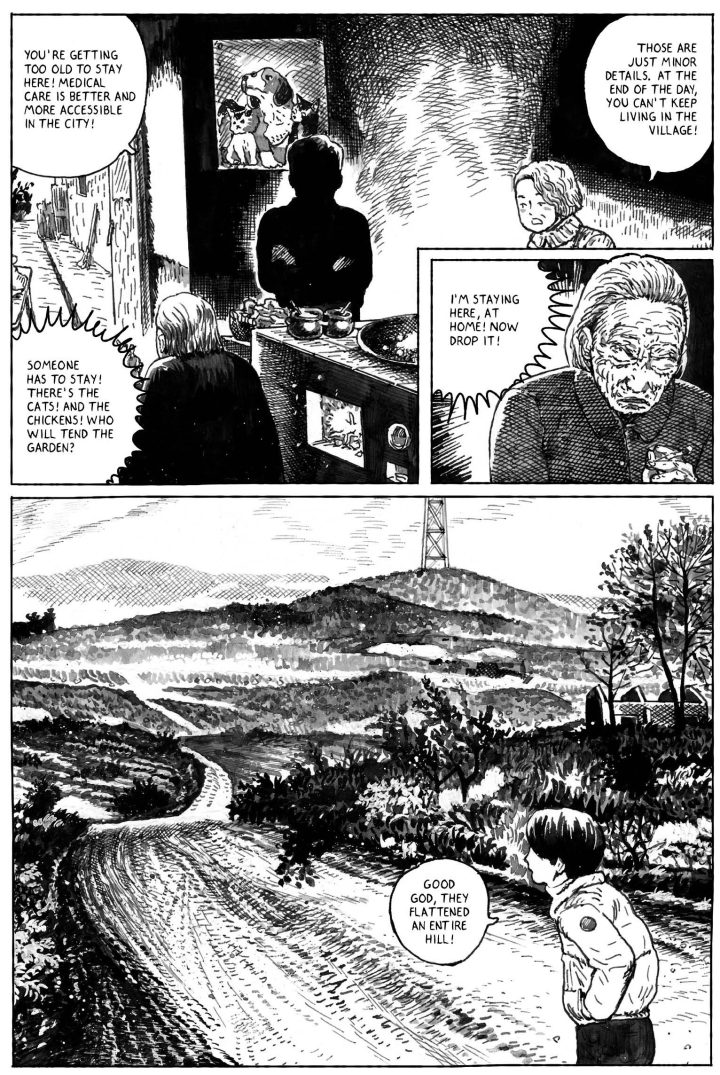

The opening short, ‘Walking Alone’, introduces us to themes that flow throughout the entire collection. We are introduced to Ma’s cartoon avatar returning from the city to his grandma’s hometown in the countryside of Central China, reminiscing with his mom, feeling at odds with some of the local traditions, struck with concern by looming urbanization, and coping with his grandma’s old age and declining memory.

The collection concludes with a reinterpretation of this story. ‘A Walk’ features many of the same notes as the original - unnerving dream sequences, vistas of agricultural land - but the rhythm feels a little different. This largely has to do with the art. ‘Walking Alone’ utilizes black and white watercolors to create a sense of a muddy, soft environment that feels somewhat untouched. ‘A Walk’, meanwhile, is ink heavy; more grainy and detailed. Comparing the pieces side by side, it’s like watching a vague memory developing detail over time.

The conclusions also differ: in the first story, Ma is left to ponder the future, and whether his grandma will move to the city. In the second, the city comes to her. Both stories start with a splash page depicting the austere interior of a rural house, but ‘A Walk’ ends with two monolithic contemporary constructions rising high, dauntingly backlit by crane warning lights. This is a collection of stories about transitions, and the effects that transitionary moments have on the individuals living through them.

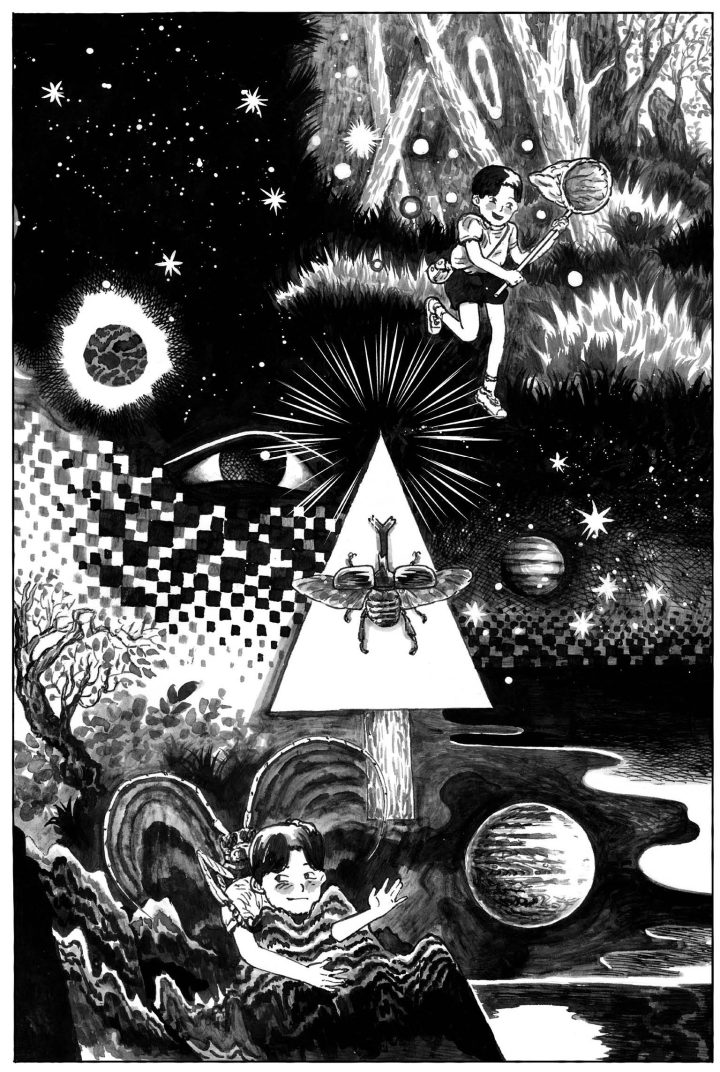

Night Bus is composed of stories told from Ma’s perspective, but he’s not always a reliable narrator. Take, for instance, the magical realist elements such as the anthropomorphized animals and the hallucinatory dreams in which Ma faces past experiences or his fears of being left alone and destitute. This may well be autobio comics, but it is autobio without desire towards vulgar realism. In its combination of the magic and the quotidian it calls to mind Gilbert Hernandez’s approach to depicting Palomar. It also feels a little like automatic writing filtered through the painstaking process of drawing comics, a combination that means the immediate, subjective spirals of thought that infiltrate Ma’s imagination are always rooted in what feels like a tangible world, one marked by uncertainty, decay, and redevelopment.

Ma takes different aesthetic approaches for the various stories. We have the aforementioned watercolors, but also more detailed inks and halftone in the likes of ‘Park People’ and ‘The Beetle and the Girl’. There’s sometimes a roughness and a sketchiness to Ma’s lines, but he is a precise and considerate visual storyteller who surely knows that less perfection helps these stories feel more visceral. This goes for the people, too, whose squishy-ness is reminiscent of Inio Asano’ s characters, and who at points have a lively, cartoonish flexibility.

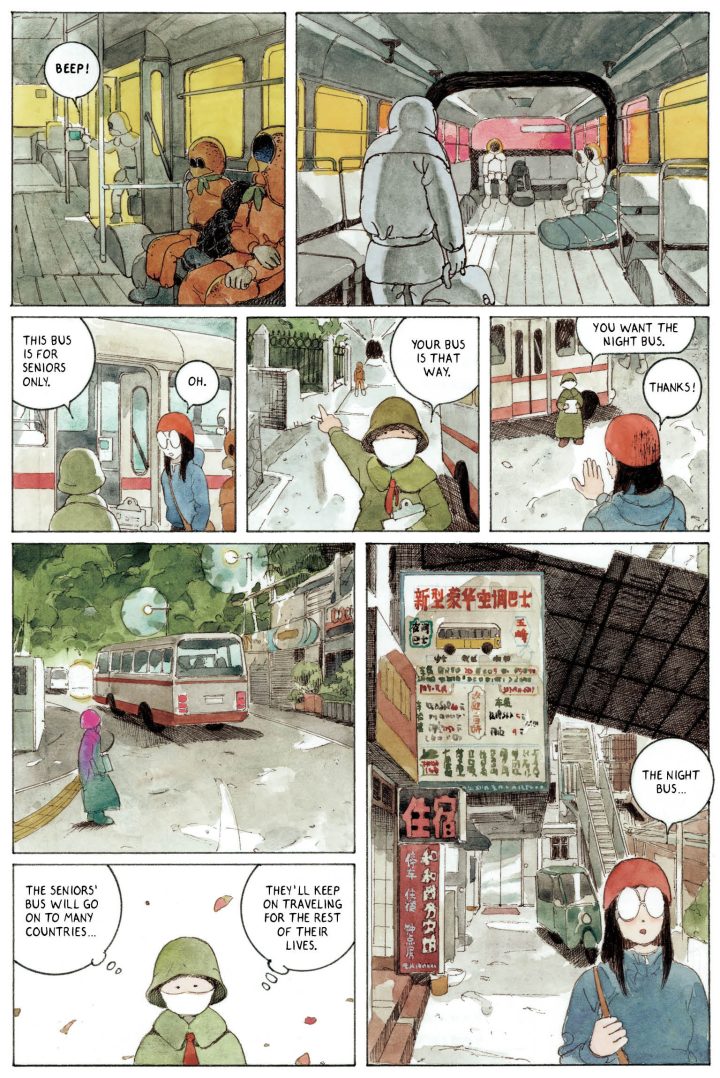

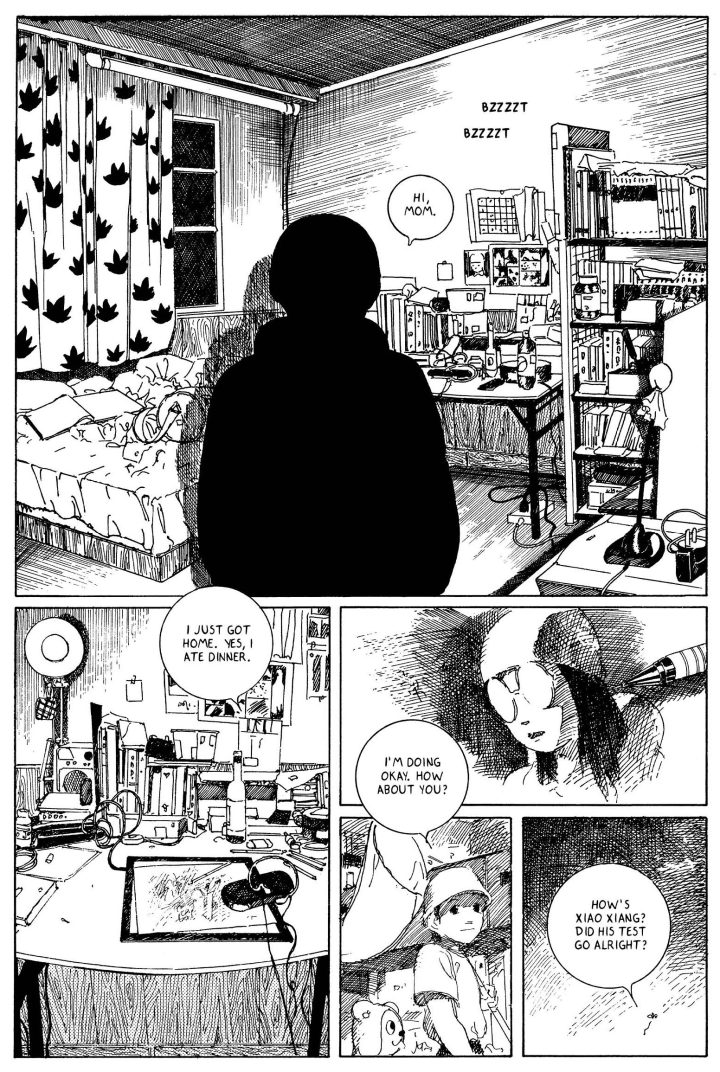

‘Night Bus’ is the only story that features colored artwork. Its opening pages are painted in soft watercolors and depict a bespectacled woman trying to find “the night bus.” Shortly, the story transitions to Ma (who here is called Xiao Jun), returning home late after work, struggling to draw his first book, and thinking about his young grandma with her round glasses. A meta element comes into play, as a panel from the woman’s adventure is repeated on Ma’s page in the “real world”. From there on in, the young woman’s story (really a younger version of Ma’s grandma) plays out in a surrealist interpretation of the world that Ma is living in. Or perhaps it’s the other way around?

Finding life in the city exhausting, Ma returns home only to find his grandma getting evermore senile. The themes from ‘Walking Alone’ are expanded on, especially Ma’s relationship with his grandma, through whom he connects not only with his childhood, but also his heritage and a China that seems to already be gone.

Young grandma crosses paths with a youthful Xiao Jun and his brother, Xiao Xiang. The confusion the grandma has with Ma is replicated here, as the younger version initially struggles to tell who is who. In this world, however, the brothers manage to get a giant fish to wreck their school and find themselves escaping an alien invasion. There’s also Fang Xiaoming, who has something akin to magical powers, and brings to life a building monster whose appearance looks like the child of a love affair between Hayao Miyazaki and Shintarō Kago.

The two storylines become ever more intertwined, to the point where the distinction between them becomes more and more hazy. On the first read I found myself getting lost between the characters and the arcs. They rhyme with each other but also seem to be in some sort of combative state, with the slow, somewhat melancholic events of Ma’s hometown being overcome with the adventure that seems to be taking place in the imaginative space he and his grandma are able to share.

The night bus itself exists in young grandma’s world as a sort of fantastical escape route. In Ma’s story, it’s the bus that no longer runs, a sign of country life in decline. What’s gone for Ma’s avatar is still real for his grandma, whose reliance on memories and past events places her in a situation where the present must indeed look bizarre and full of strange characters.

Though the story’s conclusion does its best to try and find some peace between the various narrative threads, ‘Night Bus’ is so fully packed of ambiguities and symbolism so that it retains an uncertainness, which is what makes it such a profitable read. The exact nature as to the “reality” of young grandma’s adventures is best left somewhat unresolved, as the real question is about the amount of empathy and understanding those around her in her old age can provide. Whether that’s in actual life or on the page, Ma’s goal seems to be the depiction of the ways in which memories and experiences are playful, but also sad and worrying things, interpreted and experienced differently as time goes by. Eventually, everything in memory becomes mythic, packed with fantastical creatures and improbable events.

One braided element that appears throughout this collection is the figure of Ma as a small boy with a fish catcher net, wading through shallow water, or stepping through the undergrowth in the forest looking for bugs and beetles. We first see this trope in Ma’s dream sequence during ‘Walking Alone’. Is this some childhood memory? Perhaps it is that but also a depiction of his role as the storyteller, appearing in his own memories, doing his best with perforated material to collect what of this life (and China) in transition he can capture before it is overtaken and built on with the spoils of capitalism. The aliens that appear in ‘Night Bus’ are fleshy things from outer space. In ‘A Walk’, Ma reflects on the high rises and comments “it feels like aliens have come to claim the earth.”