Once the Hollywood dollars have fled, and one or both of the multi-national corporate citizens responsible for the continued function of the North American comic-book direct market withdraw from serial publishing -- contracting the nationwide distribution of comic books to something akin to community leather-working -- the academics will isolate one phenomenon of Late Funnies as a uniquely popular expression of sociological anxiety: the debate on depictions of women in superhero art. Rare have been the weeks of the past few years when nary a word was spoken on the leering, piggish sexualization of female forms in capes, boots, and tights, or sometimes in very little attire at all. Linked to broader discussions of gender politics in the media sphere, such overdue rhetoric has achieved a rare primacy in the online conversation: sophisticated, emphatic, and current enough that it carries the very force of history’s making behind it.

Once the Hollywood dollars have fled, and one or both of the multi-national corporate citizens responsible for the continued function of the North American comic-book direct market withdraw from serial publishing -- contracting the nationwide distribution of comic books to something akin to community leather-working -- the academics will isolate one phenomenon of Late Funnies as a uniquely popular expression of sociological anxiety: the debate on depictions of women in superhero art. Rare have been the weeks of the past few years when nary a word was spoken on the leering, piggish sexualization of female forms in capes, boots, and tights, or sometimes in very little attire at all. Linked to broader discussions of gender politics in the media sphere, such overdue rhetoric has achieved a rare primacy in the online conversation: sophisticated, emphatic, and current enough that it carries the very force of history’s making behind it.

But as with all movements, there are subtleties at work inside. Where, for example, do you draw the line between beautiful, progressive, inspiring depictions of super-women and male gaze-y delineations apt for passive consumption in reinforcement of the status quo? Eh? It’s a hard question to ask of a historically male-dominated art form, one often linked by dint of influence and shared commercial status to the great illustration artists of the 20th century, some of the them practitioners of “Good Girl Art,” as the comics fans dubbed it. Nominally corn-fed and perky in presentation, Good Girl Art carries a dual charge, insofar as its idealized forms extol health and beauty and joy, while also foregrounding the exclusionary necessities of catering to male titillation.

Naturally, this latter capacity can be read as a paternalistic dictation of feminine norms to a populace who weren’t consulted on how they’d prefer to look, yet superheroes have a way of frustrating the discourse. Can’t a well-built woman inspire and empower, even from the very drawing of her? Does lady-driven cosplay not thrill in the flash and poise of it all? Don’t some women find these images beautiful, or sexually appealing? Can’t the dreams of men and women coincide?

Reverie is critical to Muse -- originally titled Songes, or “Dreams” -- a new collection of bandes dessinées drawn by Terry Dodson, a prolific 20-year veteran of the American superhero scene. It is fruitless to summarize such a long career in just a few sentences, but I think it’s fair to suppose that an artist who’s titled his homepage “The Bombshellter” is best known for his drawings of women, specifically the kind of top-heavy heroines who all but erupt, at times, from their tight ensembles, bounding into action with a twinkle and grin. But unlike the similarly-interested examples of Guillem March (who faced a terrific blowback over a Catwoman cover last year) or Adam Hughes (widely admired yet also prominently criticized), Dodson has evaded any wide denunciation for sins of depiction. He is one of "the good ones" - the girlie artists whose commitment to high-quality drawing supersedes more fundamental qualms over their aesthetics.

Fans of the stuff have anticipated this particular book for years now, as its French-language serial debut in 2006 promised a less subgenre-driven (and a more R-rated) platform for Dodson’s art; its concluding half went cruelly unreleased until 2012. Perhaps cognizant of this delay, Dodson has since declined to renew his exclusive contract with Marvel, and appears to be focusing primarily on European-market work, albeit with an eye toward speedy English translation; one guesses he found the experience of Muse, however prolonged, to be agreeable. Certainly the project’s English-language publisher, Humanoids, intends this 9.5” x 11.5” all-in-one hardcover to be a showpiece of lush, laborious art.

I think the above detail gamely identifies the appeal and the faults of the Terry Dodson style. The girl looks nice enough -- like Milo Manara and Frank Quitely, Dodson has a tendency to draw not so much women as variations on a single, "ultimate" woman in a variety of outfits and hairdos; this is apropos to a work titled Muse -- and he has a flair for exaggerated gestures that occasionally compensate for the lack of motion in his sequencing, though he cannot salvage the entirely motion-based joke that is the lowest tier of panels. It actually took me multiple reads to figure out that the lecherous dude photographing Coraline, our heroine, had fallen from his eerily still perch -- floating leaves blowing stiffly above it -- because everything in Dodsen’s panels is fussed-over and lacquered like animation backgrounds in a world without cels. Much (if not all) of the book was colored by Dodson & Rebecca Rendon directly from pencils, but this doesn’t lend the art any feeling of spontaneity, only a vaguely soft texture more easily overwhelmed by glossy digital hue.

Or, to better elaborate:

I’m generally down for a good oil-massage scene, but the effect here is frustrated because Dodson’s bodies are already so plastic -- hell, those breasts appear to be hard as ceramic, which must be murder on the back -- and the coloring so rich and heavy, that it’s absolutely impossible to distinguish moist skin from dry. And, like it or not, we are trapped with the stasis of sexy Coraline - never glistening in the frequent heat, never tottering through her myriad strippings, her ample bosom quavering nary an inch through her several under-dressed pursuits. Thank heavens splashing water offers its own dynamism! I know, of course, that you wouldn’t catch Bettie Page perspiring either, but there’s tactile expectations to bodies traveling in environments, and while you can excuse eternal cool in a superhero comic -- which isn’t really about bodies-as-bodies anyway -- a book this obsessed with a particular set of curves could do better than merely state the dimensions over and over.

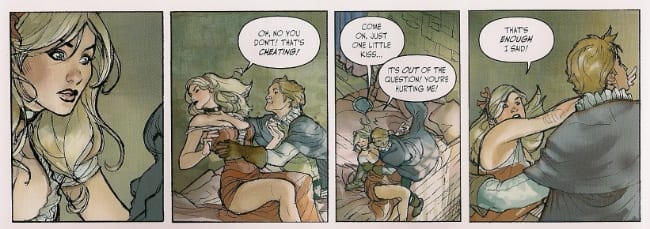

Nonetheless, the boys can’t keep their hands off ‘em:

Indeed, for as fizzy a thing at it presents itself to be, Muse is actually pretty fucking sinister for a good chunk of its page count. Veteran BD scriptwriter Denis-Pierre Filippi establishes a formula early, and sticks to it for about ¾ of the book: Coraline, hired as the new governess for a brilliant, moody, rich little boy, wanders around the sparkling grounds of the lad’s steam-powered estate, her good-hearted naiveté clashing with her charge’s self-serious nature, and then she’s somehow given a mysterious elixir and falls into a humorous dream set in the midst of some popular genre - piracy, jungle adventure, fairy stories a la Zenescope, etc. She loses much of her clothing, narrowly avoids sexual assault, slaps someone, and then wakes up.

A more provocative critic might be tempted to describe much of the book as a lighthearted look at rape threats toward a drugged woman, but Filippi is attempting to play a long game with his plot; I don’t want to give it all away, but rest assured that such naughty fantasies are duly criticized as juvenile, and that Coraline is not nearly as helpless as she seems. Which is another way of saying the plot is critic-proofed like Dodson’s bodies are sweat-resistant - complain about the content, and Filippi merely nods. “I agree,” he says, raising an eyebrow at another poor soul who Didn’t Get It.

In situations like this, it is useful to examine the counter-plan suggested by the authors, their "response" to the dominant paradigm they are largely working in yet ostensibly criticizing. The final ¼ of Muse, however, is still a barrage of underdressed women frolicking amidst bodily peril -- now with added lesbian undertones! -- but with a more focused plan for fighting back against their dream-time aggressors. This used to be called "eating your cake and having it too," but a more charitable interpretation would position Filippi & Dodson as exploring the very dual charge described above, and demonstrating how character motivation can transform identical visual tropes from exploitation to empowerment.

Yet this smut fan remains unsatisfied.

Years ago, Vittorio Giardino created a girlie comic titled Little Ego, a playful and parodic (yet distinctly dangerous) exploration of a woman’s erotic unconscious. Central to the exercise is that the heroine’s dreams are fundamentally her own: reflections of her sexual appetite. To me, this is linked to my favorite type of Good Girl Art, an approach that often fetishises women in peril, or aggressive, wicked women -- the “Good” does not apply to the Girl’s personality, but to the male viewer’s appreciation of her body -- but can also celebrate the barely-concealed licentious side of women whose lapses in demureness don’t especially detract from their character. In every movement, again, there are subtleties at work.

Muse is not really like any of that. It’s probably closest to the much-derided (if conceptually misunderstood) 2011 Zack Snyder movie Sucker Punch, which similarly plopped pretty girls down in a series of terrible dreams modeled after genre-tinged platforms for objectification, arguably contributing more to said objectification than the opposition of such. Filippi & Dodson are not as willing to go to creepy extremes as Snyder & co., but in their rush to repel the fetish imagery they’ve deliberately evoked they also act to deny their heroine any sexual agency, any desire. Cartoonist Adam Warren’s Empowered is similarly awash in potentially objectionable images, but it always portrays its own heroine as a player in the game of sex, with a full set of growling needs and peccadilloes. Coraline, in contrast, is just set dressing for metaphor.

But then, that is how she’s drawn: an icon indistinguishable from her Art Nouveau Disney Princess steampunk environs. Scratch the above paragraph - what’s really brought to mind is the mise-en-scène of Snyder classmate Michael Bay, who frequently compares images of women to those of, say, really nice cars. It’s all stimulation. Who could imagine Megan Fox having an orgasm in Transformers? That’s not her function. Look, but do not touch, because what you’ll feel is plain as drafting paper. These are depictions of women for distanced men, content with their appreciation of air-conditioned museum pieces behind the clear glass of the fourth wall.