Migraine by Woshibai and Two Stories by Gantea mark the first entries in a series of contemporary lianhuanhua translations from Brooklyn micropress Paradise Systems. Both artists are from China, the lianhuanhua tradition’s place of origin—Woshibai from Shanghai; Gantea from Beijing, by way of Urumqi—and both comics observe some of lianhuanhua’s historical conventions. Migraine and Two Stories feature one scene (or panel) per page, a horizontal orientation, and a pocket-ready trim size. Reading lianhuanhua in large quantities, the effects of this format surely vary. (Lianhuanhua of the past encompassed many genres and sensibilities, including “fables, kung fu epics, and unauthorized adaptations of foreign films,” a publisher’s note in each volume informs readers.) In the case of Migraine and Two Stories, the format supports, even underscores, feelings of stillness and ambivalence. Taken together, the comics also demonstrate how different two comics sharing these feelings can be.

Migraine by Woshibai and Two Stories by Gantea mark the first entries in a series of contemporary lianhuanhua translations from Brooklyn micropress Paradise Systems. Both artists are from China, the lianhuanhua tradition’s place of origin—Woshibai from Shanghai; Gantea from Beijing, by way of Urumqi—and both comics observe some of lianhuanhua’s historical conventions. Migraine and Two Stories feature one scene (or panel) per page, a horizontal orientation, and a pocket-ready trim size. Reading lianhuanhua in large quantities, the effects of this format surely vary. (Lianhuanhua of the past encompassed many genres and sensibilities, including “fables, kung fu epics, and unauthorized adaptations of foreign films,” a publisher’s note in each volume informs readers.) In the case of Migraine and Two Stories, the format supports, even underscores, feelings of stillness and ambivalence. Taken together, the comics also demonstrate how different two comics sharing these feelings can be.

Migraine is an autobiographical comic, or at least a comic that lets readers speculate that its subject and narrator are the same as its author. The narrator, while finishing a comic, feels the onset of a migraine and turns out the lights, waiting for the pain to end. The migraine functions as something like the worst version of a Proustian madeleine. In the dark, in deep discomfort, the narrator begins to parse his past.

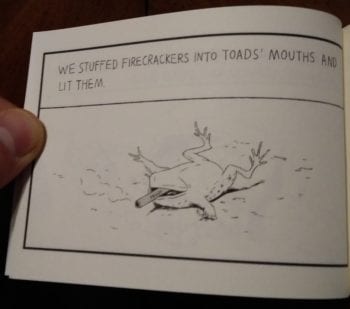

The narrator recalls first having to part ways with his mother, who leaves Shanghai for Japan when the narrator is in the first grade. He then recalls his father’s hospitalization, and following that a list of childhood fears, misbehaviors, and early sexual impulses. A number of tensions emerge across these recollections. Woshibai’s narration and cartooning both have a flat affect despite the theoretically emotive material. “I can’t say why, but I was scared of the phone,” one page tells us. “Whenever it rang, I would use a blanket to cover it.” The accompanying image shows the narrator at mid-range and against an anonymous gray background.

The narrator recalls first having to part ways with his mother, who leaves Shanghai for Japan when the narrator is in the first grade. He then recalls his father’s hospitalization, and following that a list of childhood fears, misbehaviors, and early sexual impulses. A number of tensions emerge across these recollections. Woshibai’s narration and cartooning both have a flat affect despite the theoretically emotive material. “I can’t say why, but I was scared of the phone,” one page tells us. “Whenever it rang, I would use a blanket to cover it.” The accompanying image shows the narrator at mid-range and against an anonymous gray background.

Each page is specific but unsentimental, as if Woshibai were acting as a documentarian of his own life and intent on maintaining a responsible distance. This does not making him a reliable narrator. One three-page sequence reads, “Sometimes I saw a girl in the building across the street./ We used to take off our clothes and let the other look./ I don’t really remember—maybe it was just me who took off my clothes.”

The effect of these sequences is alienating yet compelling. Woshibai’s narrator provides a litany of personal details, and even so, some readers might find the gulf between themselves and the cartoonist growing as the comic advances. Woshibai maintains this separation in part by depicting his adult and younger selves with blank, featureless faces. It’s the central gesture of a cold but memorable piece. Migraine leaves readers with some grim conclusions about the reliability of a person’s self-concept, never mind the challenge of sharing it with other people. Memory and memoir both can only help us so much.

The effect of these sequences is alienating yet compelling. Woshibai’s narrator provides a litany of personal details, and even so, some readers might find the gulf between themselves and the cartoonist growing as the comic advances. Woshibai maintains this separation in part by depicting his adult and younger selves with blank, featureless faces. It’s the central gesture of a cold but memorable piece. Migraine leaves readers with some grim conclusions about the reliability of a person’s self-concept, never mind the challenge of sharing it with other people. Memory and memoir both can only help us so much.

Two Stories, meanwhile, is less likely to stir up existential dread. Gantea has a cute aesthetic, giving her figures round heads, feet like dinner rolls, and hands like oven mitts. A reader might imagine either of the book’s pieces going viral. In addition to the cute factor, they’re quick, easy reads in basic visual-literacy terms, and they have animals too. But the net effect of these stories is something more proximal to cute; the comics aren’t Trojan horses exactly, but they’re agreeably strange at times.

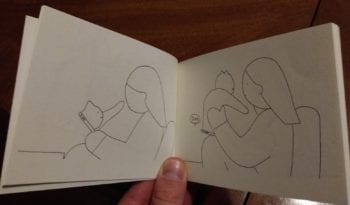

The book’s first story, “Superpower,” is a near-wordless piece about a young woman who can see a picture of an animal on her phone and then materialize it into her apartment. Gantea stages this with thin linework and a deadpan sense of humor. Beyond the gag that any decent superpower nowadays would dovetail with how a person spends their time online, the woman looks more ambivalent than excited about these animals stepping out of her screen. The scene might be more the product of imagination than a genuine superpowered occurrence—the animals disappear when the woman’s neighbor stops by—but that only makes her ambivalence odder. (Whose choice of fantasy was this?)

The book’s first story, “Superpower,” is a near-wordless piece about a young woman who can see a picture of an animal on her phone and then materialize it into her apartment. Gantea stages this with thin linework and a deadpan sense of humor. Beyond the gag that any decent superpower nowadays would dovetail with how a person spends their time online, the woman looks more ambivalent than excited about these animals stepping out of her screen. The scene might be more the product of imagination than a genuine superpowered occurrence—the animals disappear when the woman’s neighbor stops by—but that only makes her ambivalence odder. (Whose choice of fantasy was this?)

Certain small details from Gantea reward readers who don’t rush from page to page—for instance, she differentiates a dog’s butthole (a dot) and a cat’s butthole (an X)—but her compositions are sparse in general. Both “Superpower” and the second piece, “Things I Didn’t Do That Day,” feature no unneeded lines and lots of negative space, to the extent that they read not only as comics of cuteness but also as comics of absence. A useful stateside comparison is John Porcellino, whose work—like Gantea’s—doesn’t occupy a fixed spot on the continuum from cute to spare to stark.

“Things I Didn’t Do That Day” substitutes humanlike animals for the previous story’s human-surrounded-by-animals, following a cat and a rabbit on a movie date, with the rabbit making a fitful, unrealized effort to hold the cat’s hand. There are readers for whom this will be a bit too twee—Two Stories does have a barrier to entry in that regard—but “Throw Aggi Off the Bridge” proved years ago that twee done good is good indeed, and this is a good comic. Gantea uses perspective to strong effect throughout, using head-on, near-symmetrical compositions for most pages but sometimes employing more severe angles to capture the rabbit’s trepidation. The effect is something like a switch between the objective and the subjective, or the impulse to feign comfort vs. the anxieties that run through a person’s mind; with the alternate angle, the scene’s emotional stakes become more pronounced.

“Things I Didn’t Do That Day” substitutes humanlike animals for the previous story’s human-surrounded-by-animals, following a cat and a rabbit on a movie date, with the rabbit making a fitful, unrealized effort to hold the cat’s hand. There are readers for whom this will be a bit too twee—Two Stories does have a barrier to entry in that regard—but “Throw Aggi Off the Bridge” proved years ago that twee done good is good indeed, and this is a good comic. Gantea uses perspective to strong effect throughout, using head-on, near-symmetrical compositions for most pages but sometimes employing more severe angles to capture the rabbit’s trepidation. The effect is something like a switch between the objective and the subjective, or the impulse to feign comfort vs. the anxieties that run through a person’s mind; with the alternate angle, the scene’s emotional stakes become more pronounced.

Here too, Gantea’s thin line and the large volumes of negative space create an absence as much as they create a scene, suggesting everything that’s unrealized in the course of “Things.” The comic resembles a comedy of manners, but it’s not merely that—it takes the scene’s moments of hesitation and regret seriously too. Two Stories and Migraine both make for concise but thoughtful looks at the difficulty of capturing certain sensations—the difficulty of certainty, even. At their bleakest, they’re cold comfort, but they’re also a promising start to this series.