As great as the meaty action up front is, when I watch old Mickey Mouse cartoons my attention always drifts into the deep focus of the beautifully painted backgrounds. The promise of a whole cartooned world out there in the cathodes, bathed in vivid color, subject to the pipecleaner physics and superball gravity that Mickey and the gang operate under, is alternately dazzling and a little scary. As it so often is, turning to the comics is a nice solution - with everything drawn on paper by a single hand the bouncy figures soak into the backgrounds, collapsing the celluloid-layer division between the two that's a precondition of the cartoons' being.

Floyd Gottfredson's Mickey Mouse comic strips of the 1930s in particular find a perfect acme for the character in a static medium, with the cartoons' illustrative depth of field pared down to expertly balanced geometric forms. At its best, poring over Gottfredson's collected strips feels like spending hours in front of a gigantic ant farm, meticulous in its workings and flattened out like a medical diagram to be pieced together segment by interlocking segment. Like the cartoons, but in a completely different way, it’s both dazzling and just a bit scary in how all-encompassing it is.

Régis Loisel's Mickey Mouse: Zombie Coffee is purportedly "told in the daily-comic-strip-serial style of Disney legend Floyd Gottfredson's beloved early Mickey adventures," but Loisel employs a very different set of tactics to reach the same ecstatic results. Where Gottfredson's unbelievably precise drafting, sense of massive scale, and squeaky-clean lines give his work the same feel of beyond-human perfection the cartoons carry, Loisel seemingly draws his inspiration from the less worked-over backgrounds of the cartoons' quick cutaway shots or their postage-stamp views out of windows. Rendering figures and backgrounds alike in a style that nails the rounded sproing of Gottfredson, but also musses it up with scrawled, scratchy linework and slops of brushed-on color, Loisel blows strong gusts of fresh air over the placid environments of the typical Mickey outing. The more roughly hewn art gives the characters an almost maniacal urgency, while unexpected Dutch angles force a reconsideration of what foreground and background are, making the world of the strip feel fully alive - like a side-scrolling video game suddenly upgraded to immersive, open world 3D.

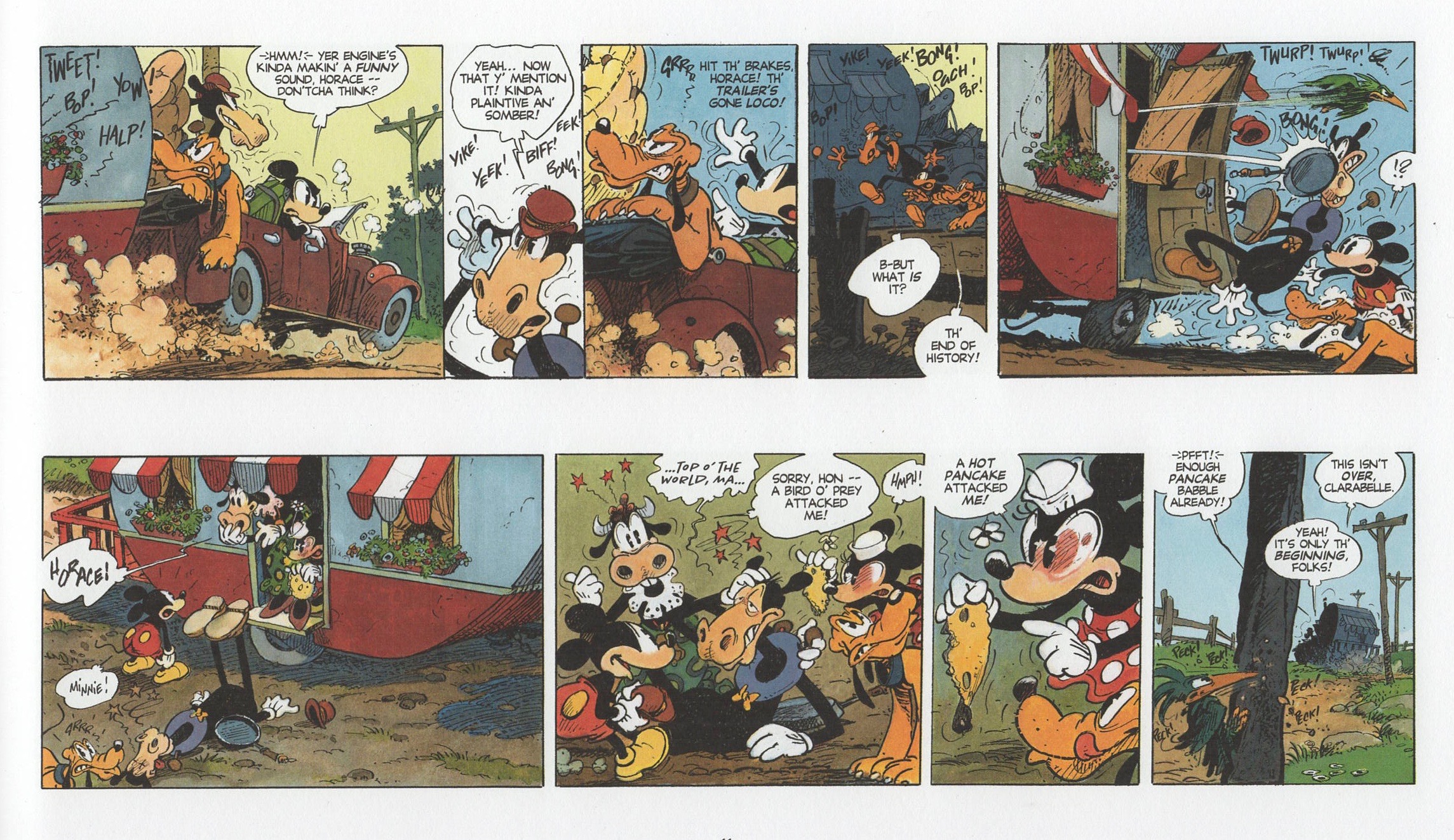

Zombie Coffee opens with a 20-page overture that shows off Loisel's technique at its best. A car-camping sequence with roots in one of the all-time great animated shorts, Mickey's Trailer (1938), it needs no real plot for its momentum. Moving through a ramshackle landscape of dirt roads, bent fence posts and alpine lakes, it pulls all of its magnetism from Loisel's gorgeous environmental drawing and the extended, hyperactive antics he paces Mickey, Donald and Horace Horsecollar through as they attempt to take their respective girlfriends camping. Pushing a boat out from a dock here is a Herculean undertaking; cooking a pancake is a recipe whose main ingredient is disaster. In this one short sequence Loisel shows himself to be capable of everything that makes the best Disney, whether comics or animation, feel so magical: the simple, homespun charm of the milieu; the nagging feeling that every element of a scene is anthropomorphic enough to cause trouble; and the way the most mundane pursuits evolve into unexpected vehicles for slapstick gags. Loisel's drawing could easily be a lot further from on-model than it is throughout this book when it has this much lifeblood running through it.

It's funny how fully Loisel inhabits such a classically American set of gestures, because his style is Gallic to the core. Loisel marries the naturalistic, earth-toned palette and dramatic lighting of European adventure comics a la Hermann or Hergé to the chicken-scratched, noodle-limbed drawing of French gag strips like Gaston LaGaffe. It's worth noting that the Disney house style's massive global impact and colonial legacy means its source code is embedded in just about any mode of comics, such that drawing Mickey probably feels like homecoming for a whole United Nations of cartoonists. Still, Loisel feels both more eased into and more excited about this stuff than most foreign publishees of Fantagraphics' "Disney Masters" line. (Check out Zombie Coffee's endpapers, stuffed to the gills with sketchbook drawings, for a look at an artist who's clearly champing at the bit.) The simple decision to stray off-model shows his confidence; it's earned by just how frantic and action-packed the set pieces feel, how the mechanisms and props involved in Loisel's elaborate choreography just feel natural.

Loisel's drawing doesn't carry more squash and stretch than the cartoons do (though it does have more than Gottfredson's comics), but by using the comics form to isolate his figures at their moments of most furious contortion, he makes the feel of his comic far more explosive. The climactic fight scene of this book, in which Mickey and Horace literally take Peg Leg Pete to the woodshed, is action comics as high-octane, well-blocked and brutally imagined as any Batman or Daredevil story from the last ten years. And the unspooling of his gag sequences, which always seem to find another prop or character entry to pivot further with, is truly intoxicating. The mere fact of a turtle swimming in a river slobberknocks six characters in sequence at one point.

As for the story - well, on the one hand, It's A Mickey Mouse Comic, What Do You Want? Loisel is smart enough to let his story act mainly as a vehicle for funny or outrageous drawings, and to keep Mickey and Donald blowing their respective tops on a regular basis. But there are bits with more juice to them than that. The Depression era setting of Gottfredson's best work isn't explicitly stated in the text, but there are references to tough times and little money that rhyme obviously enough with the Model Ts and Hoovervilles Loisel scrawls into his backgrounds. More than a callback to the Mouse's golden era or a pillar to rest a story of malfeasant bankers on, the setting allows Loisel to isolate the reason for the key element of pluck that drives so much of Mickey's character. (Gottfredson fell off as the New Deal really started working, come to think of it.) The little guy against big odds - that's Mickey as we think of him, and as we see him here.

It's also a little startling, once you see past the plot's It's a Wonderful Life decoration, to realize that Loisel has wound his narrative clock enough to synchronize with our own. Zombie Coffee's bad guys' plan to dispossess the Mouses' poor community under the pretense of urban development, and their ultimate goal of creating a sharecropping system in which everyone works for one big company's scrip, hits hard in the age of Amazon and WeWork - harder right now, on the precipice of global economic disaster, than it did when this book came out in French back in 2016. Loisel’s positioning of labor power and community action as the only way to break big business is both affecting and faintly ridiculous in the context of a Disney publication.

But this isn’t a screed, it’s a lark - one that points to how few of those there are in any kind of comics these days, and how incredible the form itself is at delivering just this kind of thing. Comics ruled in the Great Depression, a cheap and fast and easy visual form without a lot of rules and the ability to lift an audience up with just a couple panels at a time. However things have changed since then, that is comics at its best. Just be careful while you’re reading, or you’ll drift into the hogshead barrels and overgrown front yards and discarded tires of the backgrounds, hungry for more of the world that spins this story off its kilter and into a familiar kind of greatness. It's rare to see anything made with this much joy, or this much hunger.