Mermaid Saga is not Rumiko Takahashi’s defining work, but it is special nonetheless. Her longest dip into the horror genre prior to the supernatural action hit Inu-Yasha[1] and a contemporary to her domestic comedy Maison Ikkoku, this is work that feels in some ways like a retreat from the convention-scorning creative anarchy of Urusei Yatsura (which is a bonafide masterpiece of cartooning) for something a little bit more friendly to a marketing pitch. The premise is a little bit like Tezuka’s Phoenix, a little bit like Moto Hagio's The Poe Clan, recognizably austere but also certainly recognizable as a commercial manga premise by the time of the series' early 80s vintage. Like Phoenix, there are mysterious folkloric creatures which can grant eternal life, the titular mermaids, although unlike the supernatural presence of Tezuka's series they are closer to animals than deities, and are certainly not benevolent. Eating the flesh of a mermaid will either make a person immortal or deform a person into a mindless monstrosity -- “lost souls,” our protagonist informs us. One immortal who survived eating the mermaid’s flesh, a chipper guy named Yuta who looks like a cute young man but is actually several hundred years old, ambles around Japan looking for a cure so that he can age and die naturally (rather than being decapitated, the only known end to immortality’s affliction), and meets others affected by the flesh of mermaids.

In the first chapter of the series, he rescues a woman named Mana who has been raised in isolation by a commune of immortals (or so it seems) who had essentially fed off of her undying flesh to survive. Yuta is aloof and relaxed, worn down from years of experience and sadness but loving of people and curious about the world. Mana is feral and inscrutable, tough and energetic but more than a little naive. The two are drawn to each other as companions who share a strange and traumatic experience, as intrigued by each other as they are by the world -- not unlike the vampiric immortal boys of the The Poe Clan! Yuta acts as something of a guide to Mana, providing years of experience of the world and humanity which she sorely lacks, but at the same time Mana protects Yuta with her energy, her bravery, toughness and fiery emotional convictions. Each is incredibly strong in unique ways, each is immediately much more vulnerable without the other. It is the sort of instantly graspable high concept premise and simple dynamic relationship that powers a million shows airing on The Sci Fi Channel, straightforward but weird enough to generate pages of lore, vague hints of intimacy strong enough to invite powerfully personal projections for the teenage girl reader (something that, I might note, I once was). The gears that make these episodic stories turn are at times quite nakedly visible, particularly in the first couple stories presented in this new reprint. Revisiting as an adult, I couldn’t help but feel at times underwhelmed noticing how often these comics grind to a halt to ensure that you have been hooked by their premise and that the characters engage you, something that a chapter of Urusei Yatsura is far too delighted by its toys smashing together to ever really pause for.

Despite being moderately disillusioned by the machinations of manga magazine marketing and popularity poll pandering, these stories undeniably work. An immensely satisfying tour of haunting images joined to swift, airy cartooning, there is something about Mermaid Saga that lingers, a beauty and melancholy that gets under your skin to the extent that I can feel it in my breath as I type. A lot of it comes down to Rumiko Takahashi’s absolute command of her medium. The body horror imagery of the series is restrained in comparison to the explosive slapstick and comedic grotesques which bubble up throughout her comedies, but is nonetheless very vivid and disturbing, a spectre violence and evil making an incursion on the bubbly feeling of comfort the 80s city-pop manga style so readily invites. The “lost souls” are all creatures of bulging eyes and veins, lizardly protuberances lending frightening animation to a corpse. Like the titular mutant zombies of Lamberto Bava’s Demons movies, these are monsters made of abject growths, a perverse and mindless second pubescence. These are often positioned as the sort of action horror heavies that might populate the minor antagonists of a Resident Evil game, but there’s a lingering sense of loss and erasure in their every appearance, to be attacked by someone else’s nonexistence.

Despite being moderately disillusioned by the machinations of manga magazine marketing and popularity poll pandering, these stories undeniably work. An immensely satisfying tour of haunting images joined to swift, airy cartooning, there is something about Mermaid Saga that lingers, a beauty and melancholy that gets under your skin to the extent that I can feel it in my breath as I type. A lot of it comes down to Rumiko Takahashi’s absolute command of her medium. The body horror imagery of the series is restrained in comparison to the explosive slapstick and comedic grotesques which bubble up throughout her comedies, but is nonetheless very vivid and disturbing, a spectre violence and evil making an incursion on the bubbly feeling of comfort the 80s city-pop manga style so readily invites. The “lost souls” are all creatures of bulging eyes and veins, lizardly protuberances lending frightening animation to a corpse. Like the titular mutant zombies of Lamberto Bava’s Demons movies, these are monsters made of abject growths, a perverse and mindless second pubescence. These are often positioned as the sort of action horror heavies that might populate the minor antagonists of a Resident Evil game, but there’s a lingering sense of loss and erasure in their every appearance, to be attacked by someone else’s nonexistence.

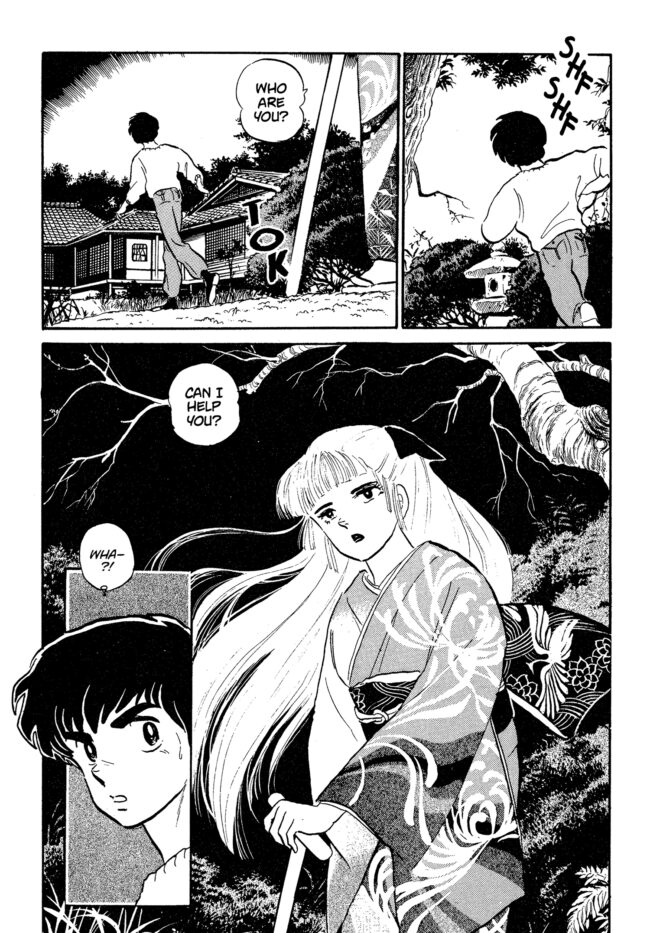

The force of Rumiko Takahashi’s cartooning could be described as dynamic movement and propulsive opposition, a clear sense of direction and invitingly animated expressions that draws the reader into situations that zigzag haphazardly from panel to panel. That momentum does appear at times in these stories, often coming to great use in scenes of running, fighting, pleading and stabbing -- the healing factor is a favorite conceit of 80s shonen manga because it allows a narrative reason for excessive and expressive quantities of gore and blood spray while retaining an acceptable amount of tension,[2] and there are numerous big moments of Yuta or Mana getting gutted in the stomach in a half page spread, dramatically impeding and contradicting their indomitable drive. But the most beautiful, memorable images in this deviate from that constant furious motion, to dwell on stillness, hauntings and apparitions. Some of the series most striking images are its most spacious and gentle, Yuta and Mana strolling down an open road, sitting on a hilltop, looking down at scattered towns cities shorelines, holding a humble quiet hope in their hearts that tomorrow will be better and there is so much to see, how simply good it is to be with someone else and share these moments. The real chiller images that carve their way into the readers heart are of ghosts, standing in place, a little out of other people’s lines of sight, staring serenely -- or maybe vacantly -- totally static, almost limp, almost floating. And by ghosts, I of course refer to beautiful women, the defining subject of Rumiko Takahashi’s craft which these stories interrogate intensely.

Time and again in Mermaid Saga, Takahashi returns to domestic structures of entrapment built around the preservation of an image of a beautiful young woman, frozen deathless in time. In some of these stories these phantom girls are innocent, powerful victims yearning to be free, in some they are actively vicious and manipulative. In a few of the best stories the woman is neither, literally inhuman, an animal, a specter or an object with the form of life and sentimental prettiness imposed on them in abject denial of their carnality, their spiritual indefinability, or their inevitable decaying descent into the grass and dirt. Yuta and Mana, chosen family, always encounter danger and strange phenomena in their travels in the form of a household whose social and even physical foundations are maintained by a microcosm of unacknowledged violence, mechanics of control to prop up a central beauty or desire against its will, hold her in place. Often they are defective applications of the mermaids flesh -- in one story, an elderly woman provides her once-chronically ill immortal sister with body parts to prevent her transformation into a lost soul; in another, a jealous suitor keeps the corpse of his dead object of desire alive and pretty with mermaids ashes, lamentably bereft of her mind. These artificial communities of hypocritical cruelty and oppressive selfishness called love are ruptured by Mana and Yuta’s arrival, but are not undone by them. Rather they are destroyed by the uncontainable ferality of the feminine spirit, at times willfully oppositional, righteously angry, grotesque, often indifferent, guided by something ungraspable by phony families. [3] These women aren’t heroines, they might not even be human, but they avenge themselves.

To my mind, Takahashi’s greatest strength as a cartoonist is as much the strength of her women -- their vividness, their beauty, their resistance to the definitions hoisted on them by adults, aroused men, readers like you. A dark mirror to the joyous romps of Lum and her friends, these stories likewise evade and subvert all expectations of how objects of desire are expected to behave without resorting to petty tropes of good girls and inevitable tragedies. Rumiko Takahashi’s manga can be ridiculously empowering and Mermaid Saga is an achievement.

To my mind, Takahashi’s greatest strength as a cartoonist is as much the strength of her women -- their vividness, their beauty, their resistance to the definitions hoisted on them by adults, aroused men, readers like you. A dark mirror to the joyous romps of Lum and her friends, these stories likewise evade and subvert all expectations of how objects of desire are expected to behave without resorting to petty tropes of good girls and inevitable tragedies. Rumiko Takahashi’s manga can be ridiculously empowering and Mermaid Saga is an achievement.

All Art: TAKAHASHI RUMIKO NINGYO SERIES © 2003 Rumiko TAKAHASHI/SHOGAKUKAN

---

[1] Although I would be remiss not to acknowledge Takahashi’s roots in horror, not only in short stories such as The Laughing Target but in her time served as assistant to the magisterial horror mangaka Kazuo Umezu, who also worked in comedy -- the parallels between the two artists invite themselves better than you would think.

[2] see also: Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure Part Four: Diamond is Unbreakable

[3] These thematic roles are remarkably reversed in Mermaid’s Scar, easily my favorite of these comics, which will be reprinted in the second and final volume of the new edition.