Gilbert Hernandez has not shied away from expressing his disdain for younger cartoonists, many of whom no doubt revere him as an influence, a key figure of the alternative comics canon. Most recently, in an interview inaugurating a new weekly strip for Vice, he admits, “I very rarely buy work from contemporary artists because they come off as awfully wimpy and self-important. Some, dare I say, even SUCK.”

It’s an offhand remark, glib and curmudgeonly, but Hernandez, a 2013 PEN Graphic Literature Award winner who has been on particularly prolific streak lately, having published in the last two years a whopping ten books—some of them, like Marble Season and Julio’s Day, among his very best—has more than more than earned his place as one of comics’ master cranks. Hernandez is either too polite or too uninformed to name any names, and I obviously don’t agree with the brush-off he gives an entire generation or two of artists, but it’s a remark that, properly interrogated, might function as a lens through which the various successes of a given Gilbert Hernandez text can be better understood. What makes Hernandez—at least in his own mind—a mainstay of the lost aesthetic of the '80s underground boom, an un-wimpy and self-effacing artist whose prolific output serves as a countervailing measure against the suckiness of even his junior label mates at Fantagraphics, Drawn & Quarterly, et al.? Put simply, what does it mean for a comic to be wimpy and self-important, how does Hernandez eschew those qualities in his own work, and what qualities does his work promote instead?

Not every text is created equal, of course, but at this point in his career, it’s a given that anything Hernandez produces is of merit, is at least very good, is worth reading at the very least to place in the context of a dauntingly diverse and impressive oeuvre. Examining Loverboys, a graphic novel published by Dark Horse that follows the torrid May-December romance between adolescent “loverboy” Rocky and his former substitute teacher Mrs. Paz, and the repercussions thereof on Rocky’s little sister Daniela, Mrs. Paz’s current student, demonstrates an aesthetic and diegetic philosophy that prizes cohesion, narrative precision, and emotional restraint.

*

By “cohesion” I mean that in terms of story, Loverboys utilizes the full canvas of its plot. Hernandez’s work is sometimes called soap operatic or telenovelistic, and this is accurate in the sense that in a Hernandez book a lot of things happen to a lot of people, and anything that happens to one person has ripple effects across the entire community. Like his acclaimed Palomar stories, Loverboys is set in a gossipy small town (this time named Lágrimas), ideal for the type of wide-scope but focused story at which Hernandez excels. As author and narrative eye, he is not satisfied with isolating a subsection of a place or group of people and telling their stories; rather he tells the story of a whole place. Even the minor characters live through distinct and affecting arcs, although much of their development happens off the page. Seymour, a wannabe loverboy about Rocky’s age who appears in just a handful of the book’s pages, begins as a Lothario braggart and is eventually humbled upon the revelation that he’s actually a thin-skinned poseur. Elmo, the town loser, and Lee, one of Daniela’s peers, are likewise little-featured characters who Hernandez nonetheless invests with enough pathos and idiosyncrasy to bring to satisfying and heartbreaking ends.

Even so, Hernandez has little time or need for exposition. For example, crucial backstory about Mrs. Paz’s history with Rocky and Daniela’s family is delivered in an offhand aside more than halfway through the book. He leaves it up to the reader to acclimate herself to his fully developed world, which is so thoroughly realized it takes a few pages to realize which characters Hernandez has chosen to focus on.

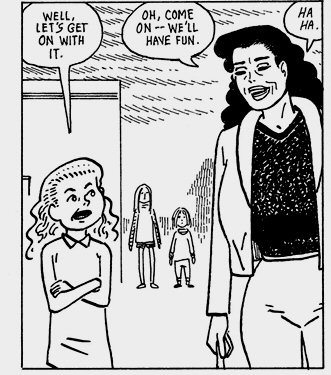

I also mean cohesion in the visual sense. Daniel Clowes has mentioned in interviews that he’s marveled at the number of people Hernandez fits into a single panel. Throughout Loverboys, Hernandez characteristically fills his compositionally simple page layouts with a plethora of eclectically designed characters whose subtleties of expression would tell a dynamic story even without textual accompaniment.

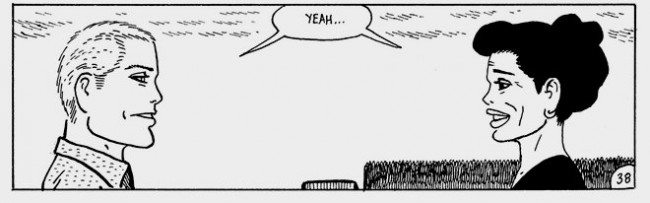

The Vice interview mentions that readers are often disappointed when meeting Hernandez at conventions because he doesn’t seem of a piece with his characters. Perhaps this reveals a way that Loverboys avoids the self-importance that for Hernandez ruins so many comics works: his self-effacement as narrator. I don’t mean merely that Loverboys lacks narration boxes or any text beyond dialogue, but that it values scrutability over inventiveness. Hernandez is a staunch traditionalist in his predilection for human acting over design. He stays out of the way of his characters, playing to the readers’ interpretation and not the author’s self-expression. Loverboys, for all its soap operatic plotting, is subtle in that it demonstrates interiority only through facial expression, action, speech, and most impressively, the use of space. To wit: One visual motif involves wide panels with two figures placed on opposite ends. Depending on context and composition, this suggests alternate meanings. Here, where Rocky and his boss Katya hint at an impending intimacy, the shadows through the open doorway draw them together:

On the next page, the white space suggests a mutual alienation:

Hernandez’s disparagement of “wimpiness” probably also has to do with his works’ espousal of emotional restraint—that is to say, not a lack of emotional effect but a carefully controlled one. Gilbert’s brother Jaime credits Little Archie writer/artist Bob Bolling as a model for managing—and not overindulging—the reader’s sentimentality, and Loverboys shows the same influence, primarily through Gilbert’s thoughtful elisions. For instance, one character’s apparent suicide is rendered only by an image of that character looking thoughtfully at the beach from atop a cliff; pages later another character finds his trademark hat in the sand. Loverboys also shows Bolling’s influence in terms of subject matter and point of view. Despite the way the book has been marketed and packaged, this is as much or more Daniela’s book as it is Rocky’s or Mrs. Paz’s, and not unlike the work of Bolling or John Stanley or Hernandez’ own Marble Season in its unsentimental portrayal of childhood. Unlike his brother Jaime, whose decades-spanning Locas stories have taken their characters into the doldrums and compromises of middle age, Gilbert explores genuine trauma through the hopelessly rational, questioning, and wounded eyes of children and adolescents, with little patience for the adult nonsense of work and ethical grayness; all we hear of Rocky’s career is vague mumblings of “deliveries coming up short” owing to an “error,” and Daniela’s friend Lee’s thwarted infatuations with both Daniela and Mrs. Paz are treated with as much seriousness as any adult relationship, possibly more.

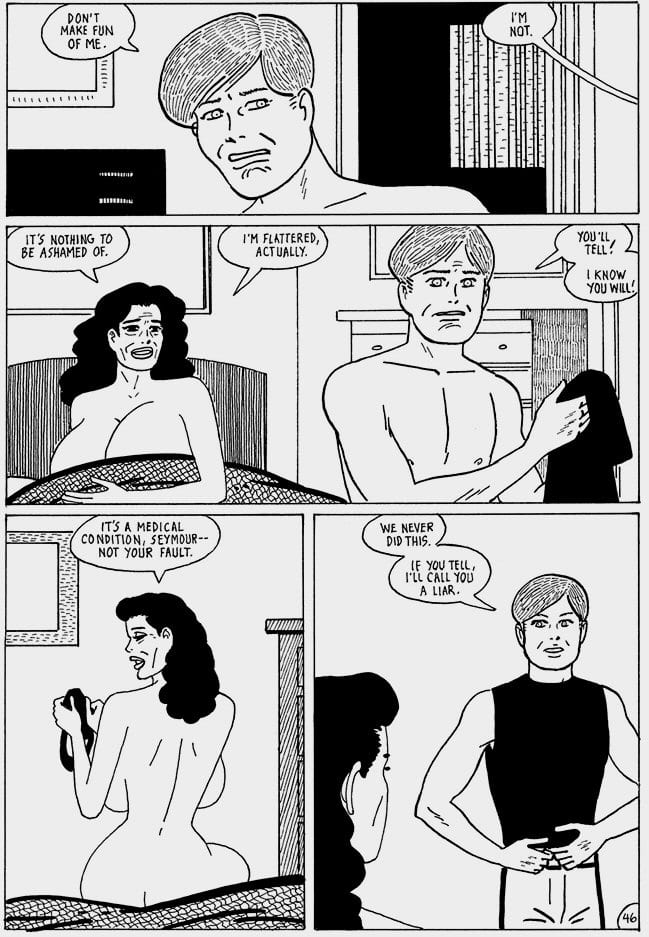

Finally, Hernandez’s typically clear-eyed, unleery and non-judgmental approach to sex is decidedly anti-wimpy. Almost no cartoonist other than Hernandez takes sexual expression as his or her subject matter with as much confidence and insight. His sex scenes are at once artistically, gleefully gratuitous, and crucial to character development.

All of this is not to say that Hernandez succeeds where other younger, wimpier, self-important artists fail. It merely explains the unique and inimitable appeal of a Beto book and perhaps illuminates why much of the contemporary comics landscape fails to meet Hernandez’s high expectations for the medium. And how could it? Hernandez is one of the best ever—one of the best creators and naturally one of the best informed readers as well. Loverboys is an overlooked triumph, perhaps equal to his recent high watermarks Bumperhead and Marble Season.