I

Some people learn from their mistakes, but they aren’t usually very interesting people.

Having been away from comics for well over a year doesn’t just mean abstaining from crap. I hadn’t seen an issue of the new volume of Love & Rockets, and truth be told am still behind on the last volume of New Stories. That needs to be said up front because it’s important to recognize that any issue of Love & Rockets taken in isolation is incomplete. I’ve read almost everything Los Bros have ever done but the saga at this point is so massive, and takes a significant time investment to get back up to speed, that I usually save up a few stories at a time. On their own and by design individual chapters rarely add up to much.

That’s something about both Jaime and Gilbert, as they got older and their respective serials eased into the comfortable rhythms of mid-life: saying each chapter seems slight on its own is hardly an insult when the sum is immeasurably greater than its parts. At this point even the idea of something as distinct as “story arcs” seems like a mundane imposition. Maggie & Hopey’s lives, to say nothing of those of Fritzi and her extended fractious clan, don’t fit into beginnings, middles, and ends. Maybe every now and again events cohere into distinct climaxes and denouements, but mostly things just keep going one damn thing after another. You know, like life.

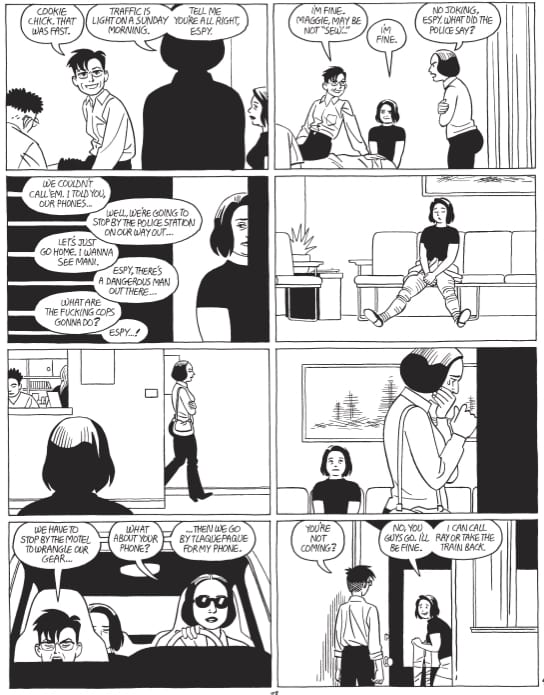

The thing with life is that meaning doesn’t accumulate around a single snapshot. Meaning accumulates around multiple snapshots, coalesces often out of the simple act of memorializing change. The main “story” of Jaime’s section of the book focuses on Maggie & Hopey in the present being chased through the night by a bigot in a plaid shirt. It’s a crappy night, sure, but a crappy night in the way that only crappy nights can be when they actually don’t turn out so bad after all. Because even though they got into more than one screaming match with more than one bigot and then Maggie fell in the middle of the road splitting a pair of pants down the middle, they still were out carousing at all hours of the night. Y’know, like they used to in the days before Hopey wore corrective lenses. Before I wore corrective lenses.

Even though the letters page informs me that the Maggie & Hopey strips in this issue are the climax of three years of stories, well, three years is about how long it’s been since I last checked in. I didn’t have any problem keeping up. These tales hang on their own – you don’t really need to know why they’re being chased by the guy in the plaid shirt to get the gist of the conflict. On it’s own it’s a fine vignette, a tragicomic story like any wild night taken out of context. I’m sure in six or eighteen months when I finally see these chapters in context, probably when they have a hard spine, I’ll find a lot more. Something to look forward to, without a doubt.

The pleasures of following any long-running serial are many. If you have a busy year or three it’s good to know you can always press pause and come back when you have the time. How many other serious relationships have you ever had that work out quite so well?

II

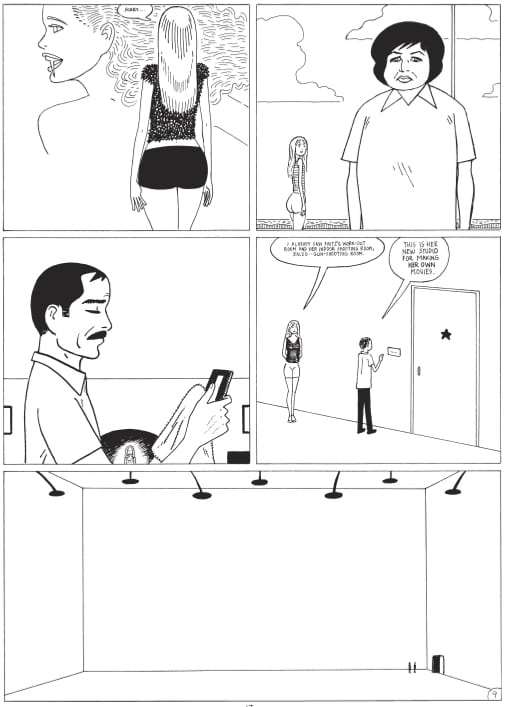

The worlds inhabited by Fritzi – the center of gravity for many of Gilbert’s post-Palomar stories – are barren and forbidding. The name of the story is “You’re right, it’s not about you,” and these words appear as tiny letters dwarfed inside an elephantine caption box. As with most of the women in Fritzi’s orbit, Rosario is dwarfed by her mother’s outsized presence both in the outside world where she is a famous actress and in her family, where she is charismatic and brilliant enough to just sit around talking about calculus with her other daughter. You know, like normal people do who aren’t also very insecure about their intellect based on their being heavily judged on their looks every damn day.

Gilbert continues to mine the narrow territory between “frigid” and “surreal,” which to be fair is a relatable place within a lot of peoples’ extended families. Sometimes it’s difficult to get a feel for where different characters are in these stories because, even after decades of familiarity, Gilbert still relishes every opportunity to catch his readers flat-footed.

His stories have always been heavily and keenly attuned to the way women slight and snub each other when men aren’t paying any attention. It’s not always intentional, but characters like Rosy often exist to be overshadowed by more charismatic, effervescent or simply just buxom characters. These kinds of conflicts are primal to his stories, going back to the complex relationship between Chelo and Luba in the earliest Palomar chapters. What has changed in recent years is that the tenor of the American Palomar stories is now and has been for a long time cold. There’s no warmth in these peoples’ lives and the absence makes itself felt in every aspect of their pervasive unhappiness.

It’s a compliment to say that Gilbert’s layouts here are alienating, because they’re meant to be. Very few people in the history of comics have ever been as confident in their ability to use an inordinate amount of negative space and hold their readers’ attention. Rosy’s been left alone for a few day’s in Fritzi’s massive house so much of the story is her simply walking around a mostly empty and cavernous mansion haunted by the ever-present spectacle of by her mother’s massive breasts. The emptiness seems eerie to Rosy in the story, and it’s eerie for the reader at home to see the emptiness erupt across the page.

It’s a compliment to say that Gilbert’s layouts here are alienating, because they’re meant to be. Very few people in the history of comics have ever been as confident in their ability to use an inordinate amount of negative space and hold their readers’ attention. Rosy’s been left alone for a few day’s in Fritzi’s massive house so much of the story is her simply walking around a mostly empty and cavernous mansion haunted by the ever-present spectacle of by her mother’s massive breasts. The emptiness seems eerie to Rosy in the story, and it’s eerie for the reader at home to see the emptiness erupt across the page.

Every time I check in it seems as if Gilbert keeps inching closer to going the full Ditko with his line – that is, by condensing decades of skill to measure the absolute minimum of technique necessary to communicate spatial relationships between small creatures trapped in tight panels. Later Gilbert is not a place to look to find humankind buoyed by harmonious interface with its environment. Whole pages pass with Rosy as a tiny stick figure against massive fields of empty white space. It’s uncomfortable to see.

The massive fields of whiteness in the present are contrasted throughout the story with scenes from one of her mother’s sci-fi pictures, filmed a decade in the past and covered in the inky spotted black of deep space. We are helpfully informed that this was the one the critics actually liked, primarily because she’s wearing a space suit that covers up her breasts for the whole movie. The effacement of her breasts is a motif throughout the story – they’ve been erased from movie posters throughout the house, “as not to offend the faint of heart.” The effect is that Fritzi appears torn in half, a literally disembodied presence looming against the background behind her tiny daughter.

It’s hard not to see why Rosy has such a hard time of it, since the story presents her a stark choice between standing in front of her mother or standing in front of nothing at all. She doesn’t seem to see any resonance between her dissatisfaction growing up in her mother’s shadow and her mother’s dissatisfaction at having to live in the shadow cast by her own fame, and her obvious feelings of hollowness. But of course Gilbert is careful not to show his characters ever actually inching any closer to understanding themselves. To do so would be to admit they’re trapped in empty hells of their own making.

III

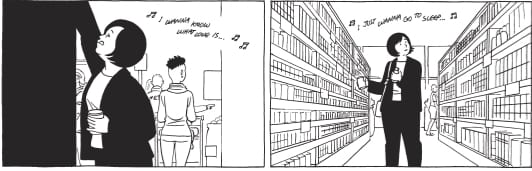

Hopey never learns from her mistakes, either, although she can usually pretend enough to be able to cadge a ride home. That’s sort of the “moral” of the Jaime stories here, if you can call anything so obvious a “moral” – Hopey only ever learns from her mistakes by being distracted enough to move on. Leaving who knows what in her wake, but they’re probably better for her absence.

That isn’t a good way to live. People who live like that burn themselves out on people, fall in and out of peoples’ lives like seasons. Just like Hopey: Not very dependable. Kind of a flake. Actually a big flake. A jerk to the people who love her most. An absolute hair-trigger temper. And yet also completely irresistible to certain women, who forgive her over and over and over again even though she refuses to ever actually settle down even long after technically she is already settled down . . .

Jaime’s art continues its steady march towards a rendezvous with a similar kind of minimalism as his brother. But it’s less subtractive than gestural. He does more with a few lines of body language than most artists can do with a raft of cross-hatching. I don’t know if you can stand the heat from this scalding Hot Take: Jaime Hernandez sure can draw purty!

Jaime’s art continues its steady march towards a rendezvous with a similar kind of minimalism as his brother. But it’s less subtractive than gestural. He does more with a few lines of body language than most artists can do with a raft of cross-hatching. I don’t know if you can stand the heat from this scalding Hot Take: Jaime Hernandez sure can draw purty!

This is The Comics Journal! I mean . . . even I’ve written about Los Bros for The Comics Journal before. What is there new that could possibly be said about such a well-worn topic in such a well-worn venue at such a late date?

How about this:

The first social media icon I used as a woman was a sketch headshot of Hopey I found off Google. She’s young in the sketch, as young as she was in the early run of the book, but also caught in a rare moment of uncharacteristic thoughtfulness. Still unmistakably her. That was the first face a number of the people I consider now to be my best friends knew me as, when I was still very much closeted and afraid, living out the last desperately busy and fraught months of my life as a putative cis man.

It wasn’t a random choice. I had felt a bond with the character from my first encounter, although I didn’t understand why until recently. I don’t act like her, really (or rather, I hope I don’t but probably do more than I’d like to admit) . . . but if we’re being honest I do basically get the same haircut she did when she was in her twenties, give or take a bit of symmetry. And I wear boots. And we actually sort of both got glasses the same year, and seeing her go through that gentle but firm aging milestone with as much grace as she did was a big influence on my doing the same. And yeah, I guess she was my formative dyke role model, back before I had more than a general idea of the type as it appeared in media, and certainly way back before I had any inkling I was trans. Her creator wasn’t even a lesbian, for goodness’ sake!

However, no one ever seems to criticize Los Bros for representation issues. I certainly wouldn’t be surprised if it had happened at some point, but if it has it’s never been loud enough to reach my ears in the decades I’ve been paying attention. (Which could only mean I have cotton in my ears, certainly.) But my point is that it’s a hard portrayal to criticize because it feels real. There’s nothing off. This is how certain people act, how they dress. Perfectly observed. Never feels like anything less than a fully compelling and fully realized person, not just “A Lesbian” but a bunch of different other things, including Latina, bass player, and occasional louse. She reminds me of a lot of people I know who would probably be flattered by the comparison, if they got the reference.

However, no one ever seems to criticize Los Bros for representation issues. I certainly wouldn’t be surprised if it had happened at some point, but if it has it’s never been loud enough to reach my ears in the decades I’ve been paying attention. (Which could only mean I have cotton in my ears, certainly.) But my point is that it’s a hard portrayal to criticize because it feels real. There’s nothing off. This is how certain people act, how they dress. Perfectly observed. Never feels like anything less than a fully compelling and fully realized person, not just “A Lesbian” but a bunch of different other things, including Latina, bass player, and occasional louse. She reminds me of a lot of people I know who would probably be flattered by the comparison, if they got the reference.

Perhaps Hopey isn’t the best role model, but there are worse. At least she’s free, just like me.