There's plenty to like about this new dystopian-future monthly from Image. Pick up a copy and it's easy to figure out where to start: artist Ian Bertram, whom I last encountered as a highly impressive but slightly miscast bit player around the edges of the Batman line, swinging for the fences on every page. With Matt Hollingsworth's colors draping luminous fuzz over every surface, this comic looks better than anything else that's come from its publisher in awhile. On Batman, Bertram's drawings called Frank Quitely most forcibly to mind. Here, in a less familiar and more fantastical setting, strains of Rafael Grampa grit and Tsutomo Nihei sinew float closer to the surface, and bits of visual shorthand imported from Alejandro Jodorowsky's Incal universe are welcome surprises.

Still, to my eye at least, Quitely is the most apparent influence on the way Bertram draws. This isn't surprising; as one of a very few modern cartoonists whose work on corporate properties hasn't led to a bibliography comprised mainly of bad comics, Quitely is cruising toward elder statesman status these days with an ever widening circle of published acolytes. Bertram flexes a strong individual style while picking up on two important, underappreciated aspects of Quitely's: his markmaking and his passion for grotesquerie. Bertram's forms are his own, but they're shaped with profusions of crabbed, gossamer-thin lines that rarely extend for more than a centimeter before breaking off a micron from another, nearly identical stroke. Quitely fans will recognize this impressionistic, almost sculptural approach on sight, but Bertram brings a more frenetic, compulsive hand to his pages, locating a strong gristle of connective tissue between Quitely and Dave Cooper. And like Quitely, just about every one of Bertram's characters are imbued with Extreme physicality: a Strong guy looks like an NFL lineman with hypertrophy, a Regal dude's robe-swathed legs extend well over twice the length of his torso, a Small girl approaches a lithe brand of dwarfism. This is influence properly wielded, not copycat work but an identification and exploration of shared strong points.

Bertram is less solid with what I consider to be Quitely's most important skill: establishing shots. He's not far off the mark - his wide shots are frequently impressive, well composed with groupings of characters' proximity to one another clearly displayed. But too frequently, the set-ups that these panels provide are left hanging, with turns into the visual illiteracy of action movies and superhero comics, respectively: smash cuts between shots of individual characters, their forms vivisected by the borders of extremely short, wide rectangular frames. This tendency, combined with a too-frequent penchant for dousing scenes in lightly stippled banks of vapor, leaves Bertram's design for his comic's world with a grade of Incomplete. What you can see is intriguing, but the book's events sometimes feel more like they're taking place against the background paintings in an old movie than within a three-dimensional environment.

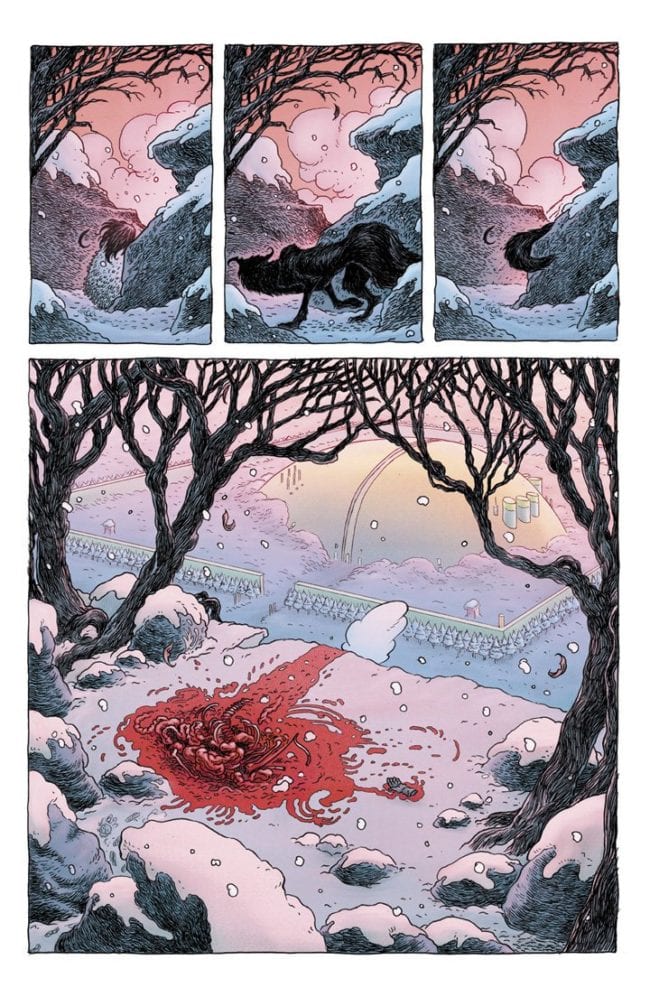

This is a shame, because in sequences that stick to a more traditional gridlike layout or give their compositions more room to breathe - mostly the fight scenes - you can see a really good cartoonist shining through the fog. Bertram has a genuine talent for really selling the extreme gore Little Bird ladles out: most violent comics' slashing dismemberments and buckets of blood are rendered rote by indifferent visual treatments, but Bertram gives them his all, finding a more immediate, impactful level than a lot of books ever muster. A sequence of a dude being roasted to death by the kind of energy-beam-or-whatever weapons that every single action comic features without ever showing the effects of, his skin crisping and bubbling nice and sloooooowly, is indelible, and there are a few scenes of knife play that harness a whirling kineticism even the movies have trouble putting across.

I haven't mentioned the story yet, because it really is a little tough to know what to say. Writer Darcy Van Poelgeest comes to comics from filmmaking, and is clearly conversant enough with the similarities between the forms to know when to get out of the way and let shit explode. This alone is noteworthy: nominal "action" comics are often too interested in creating a slow burn (or even worse, a "mythology") to do their job correctly. The rest of the writing, however, seems as obscured by haze as the specifics of the world Bertram draws for it. Little Bird is a Good Vs. Evil thing of course, with a repressive theocracy's implacable minions intent on hunting down and eradicating a final pocket of superheroic resistance - so every third action sci-fi comic, basically, but without an iota of the personality the good versions of such bring to the table. Little Bird, the vengeance-obsessed adolescent protagonist, is a total cipher, as is the Wolverine-lite hero who acts as her protector. The bad guy, a monomaniacal leader of church and state, is even more absurdly generic, a xeroxed retread of the "creepy pious dude" from Indian Summer and The Technopriests and Preacher and God Loves Man Kills and V For Vendetta and The Authority and so, so, so so many more.

As of issue #3 the plot's still in the "little conflicts along the journey to the big conflict" stage, but I'm sure it'll get to the "violent collision that fails to explain how it redresses any of the damages wrought by an oppressive regime" part pretty soon. I know, I know, it's just supposed to be a fun action comic, but there's also a truly striking lack of any discernible forward momentum in the way Little Bird unrolls its well-worn story. It all just kinda happens, with no emotional affect pointed to or seemingly even attempted. The spotlight switches back and forth from heroes to villains in what's clearly supposed to be a ratcheting up of tension before a cathartic clash, but it's utterly lacking in frisson, in any indication that we should care about what we're seeing or incentive to do so beyond the fact that turning another page of this comic will probably result in seeing at least one additional cool drawing. Dialogue fails to put flesh on any individual character's bones, and the internal monologue/narration in the occasional caption boxes never becomes anything but a distraction.

Part of this pervasive blandness is undoubtedly due to Van Poelgeest's film background. In film a writer who plays in this area of genre doesn't have to do much more than flick the burner on to bring tension to a boil when emotionally manipulative musical cues and scenery-chewing performances from professional actors are also at their disposal. There are tons and tons of other people pushing their own highly specialized levels of craft to the limit in service of a movie writer's vision - but in comics the few involved all have to pull a lot more weight. Bertram and Hollingsworth provide the comics equivalent of high quality production design, cinematography, editing, lighting, and choreography, but none of those will save a poorly written movie starring bad actors. At best, you'll get a product like what this comic is: something with bits here and there that are good enough to make you forget for a second that you're gutting your way through a piece of what must ultimately be classed as bad art.

Saying some of this, I feel I'm being hard on what is after all a first timer creating a solid example of this particular type of story done in this particular medium. But any lingering goodwill for Van Poelgeest's contributions to Little Bird vanishes with his (or Image's) insistence that what you're reading isn't just entertainment - it's #relevant. Van Poelgeest's refusal to show his audience a single scene focusing on the non-murder policies of his villainous regime, or their effects on the common citizen - or even to confirm the existence of any common citizens! - reduces this comic's plot and characters to a set of empty signifiers, vastly lowering its own ceiling. Which, fine! It's still just supposed to be a fun action comic, even though that excuse is getting stretched pretty thin by now. But it's nothing new, and some of the other versions of this out there are much better, and what Van Poelgeest is giving us really isn't all that relevant: there are like three or four other forms of bigotry doing worse damage to our social fabric right now than religious hatred is.

Worst of all, this comic is intellectually dishonest. Positing Evil as an overwhelming, malevolent force to be heroically defeated is, yes, Part of the Problem. If you're concerned about totalitarianism and theocracy, the first thing you need to admit to yourself is that life isn't a fucking action comic. Evil is a bunch of ignorant incompetents who keep failing upward, abetted by useful idiots who are still too obsessed with their vigil against some Star Wars/Jodorowsky bullshit happening to stop the actual bad guys from getting away with it. Creating a story where every character is Chosen or Special or Super or Crazy leaves Normal people who might be inspired to action by actual relevant art with two options: the solipsism of turning the page hoping to see at least one additional cool drawing, or putting the book down. If Image's latest bid for timeliness was supposed to make us all realize that the closest we can get to legitimate resistance while still reading comics was to stop reading stuff like this one, congratulations?